Solidarity as a guiding principle in life

advertisement

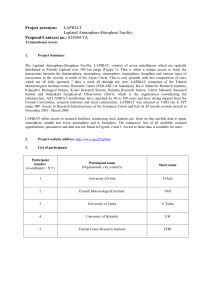

1 Hilkka Pietilä: Published in the book: Hakkarainen, Toikka & Wallgren (Ed.): Dreams of Solidarity. Finnish Experiences and Reflections from 60 Years. Kepa & Vasudhaiva Kutumbakan. Keuruu 2003. Solidarity as a guiding principle in life My “globalization” started early The ”globalization” of my thinking started as early as at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s. The further I have proceeded in this globalization process, the better I understand the destructive nature of the market driven economic globalization. My globalization began when I realised in the late 1950s that I knew nothing about the extent of starvation within humanity, how every year millions of children wasted away by deficiency diseases due to lack of healthy food. I knew nothing of this reality even though I had studied nutrition for five years at university and had even graduated. I then became the secretary, alongside my regular job, for the household and nutrition section of the National Commission for the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) in Finland, the benefit of which was that I began receiving the material from the FAO. I experienced a kind of cultural shock – how can nutrition be taught at the university and yet people graduate ignorant of the world’s reality? They do not learn what happens to children when they do not get enough milk, and thus not enough proteins and vitamins. They do not learn that a lack of proteins and vitamins is not only a matter of theory but a reality on a massive scale in this world. Since I did not see what else I could do, I started to inform people about the world situation by writing articles based on FAO material. I could even combine this information with my job then as the secretary-general of the Milk and Health Association. My job was to inform and enlighten Finns on how valuable milk and milk products are for nutrition. What could have been a more convincing way of illustrating this than to show what happens to children when they do not have milk enough? I came across plenty of material on the world situation once I learnt how to search the FAO, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and other sources. Even though I had grown up in wartime Finland, it was only in the 1950s that I began to understand how much we were in need for aid in our country during and after the wars in 1939-1944. UNICEF helped Finland to improve children’s nutrition, healthcare and clothing from 1947 to 1955. Hunger and malnutrition were so close in time. UNICEF helped Finland, for example, to initiate the pasteurisation of consumer milk so as to guarantee its hygiene as basic food for children. This was where I started. In 1961 my article entitled, “Thirty-five million will starve to death this year in the world”, was published in a weekly magazine. This was the start for the FAO world-wide Freedom from Hunger Campaign in Finland. Later the national campaign committee was founded and I was asked to join because, in a way, I had already started the campaign. At about that time I also got an opportunity to patch the hole in the university teaching at the Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry by giving lectures on the world food situation. 2 In 1962 a book by the Swedish-born American professor Georg Borgström “Mat for miljarder” (Food for Billions) considerably complemented my knowledge of food production. I began to understand how wasteful food production was in rich countries and how it was continuously “developed” to be even more so. Intensifying agriculture by mechanisation and increasing use of chemical fertilisers and concentrated fodder means that it becomes increasingly wasteful of energy. Even transforming grass and grain into meat is extremely uneconomic. For one calorie of meat we need eight calories of vegetable energy, which Borgström called primary calories. Despite that the living standard of westerners is measured by the consumption of meat per capita. All this proved to me that continued growth of consumption in rich western countries increases global inequality and exploits the global natural resources. People in the rich countries are literally taking bread from the mouth of the poor when they waste the world’s limited energy resources and food production capacity by their conspicuous consumption. That is why one form of practical solidarity is to oppose the growth of consumption in rich countries. This is an issue I have tried to convey in all the information and awareness-raising activities that I have been doing over the decades. In 1963 I gave up my professional field as nutritionist and took over the post as the secretary general of the Finnish United Nations Association, an association for education and public information about the principles and activities of the United Nations. Thereafter I could devote myself full time to the international work. Widening inequality gap The food problems in the world have not been resolved despite the efforts made in last fifty years. The number of people starving has not significantly declined but has remained at about the level of 800 million, even though their relative share of the growing world population has declined. It is an achievement that world food production has roughly managed to keep pace with population growth, so the whole situation has not got totally out of hand. The gap in consumption has instead widened explosively with markets in industrialised countries stirring the growth of consumption and governments pursuing corresponding policy at full force. The World Conservation Strategy (WCS) published in 1980 cautiously estimated at that time that a person in the industrialised countries consumes on the average as much as 40 inhabitants in Somalia, for instance. In the 1990s it was shown that the strain on the world’s natural resources caused by an average American is equivalent to that of 140 people in poor countries. In the 1970s E.F. Schumacher outlined in his books “Small is Beautiful” and “Good Work” an economic and development model for the industrialised countries that would secure the quality of human life but at the same time limit production as well as wasteful and environmentally destructive consumption. About the same time Ivan Illich, Rudolf Bahro, Andre Gorz and Erik Damman made many suggestions on what could be done in the industrialised countries to stop growth. They devised an economic policy aimed at scaling back consumption instead of its continuous growth. Among others, Rudolf Bahro proposed that production in the rich countries should be reduced by 90 per cent in order to create room for the developing countries to increase their production so as not to exceed the carrying capacity of the earth. The famous Club of Rome published its report “Limits to Growth” in 1972 using the predominant trend at the time, a computer scenario demonstrating where the world economy would head to if growth was maintained at the then prevailing rate. The Club of Rome made the mistake of not indicating clearly which countries should limit their growth. Therefore despite its prestige, the 3 Report was denounced from all sides: the industrialised countries did not accept the idea of limiting their growth, and the developing countries rightly did not see why they should stop growth insofar as the majority of their people were still living in poverty and scarcity. I took on all these wise ideas with great enthusiasm as they helped me to understand why there is such extreme inequality between people and nations in the world and why the situation is continuously deteriorating. Already then I had doubts whether the development cooperation would ever be able to stop the gap from widening, not to mention whether it would narrow it, valuable though development co-operation is in principle. If we really want to reduce injustice and promote equity in international relations we have to transform the development patterns and politics in the North. In 1970 we at the United Nations Association published a small handbook for use in schools and youth clubs on basic knowledge about the developing countries where we showed the direction in which we were headed. Already at that time the debt of the developing countries alone was of the magnitude that its interests and amortisation took up as much money as all the development aid from the North. In addition, we referred to how much profit big companies repatriated from developing countries every year and how the terms of trade were progressively getting worse, with developing countries losing out not gaining. The booklet was well received and it ran to three editions, with thousands of copies distributed. The public interest in development co-operation and environmental protection grew rapidly throughout the 1970s. Many people wanted to go to work in developing countries or to participate in development projects. It was then that the first attempt was made to initiate the Finnish volunteer service. However, the campaigning was mainly aimed at increasing the Finnish development funding allocations. The ideas of reducing production and consumption in the North and changing the goals and principles of economic and trade policies did not find much sympathy. The decade of transformations - 1970s The 1970s was the United Nations Second Development Decade. For this decade a particular development strategy was designed and adopted contrary to the First Development Decade of 1960s. However, this strategy outdated quickly because it was overtaken by events in the 1970s that advanced development in an unprecedented manner. Right from the beginning of 1970s women rose up against the strategy because it mentioned them only in passing. So the UN Commission on the Status of Women drafted its own strategy in which women put forward their own demands and set their goals for development. As a long substantive resolution this strategy was adopted in the autumn of 1970 alongside the Development Strategy. In 1972 it was decided to declare 1975 as International Women’s Year, during which the first World Conference on Women was held in Mexico City. These events created a snowball effect that changed the functions of the United Nations system ever since from women’s point of view. In 1972 the first UN Conference on the Human Environment was held in Stockholm. The environmental problems were outlined more holistically and broadly than what had been done by the environment movements up to that time. The issue was not only environmental destruction and nature preservation but also the utilization of natural resources and the impact of so-called development on the environment. The conference also dealt with the inhabited environment, environmental education as well as the social and cultural dimensions of environmental policies. The use of natural resources and the problems of pollution were dealt with as global problems and 4 not just as national and local problems. Aid is not enough Already at the beginning of 1970s many developing countries had reached the conclusion that development aid alone cannot make up for the inequality between the North and South, which is rooted in hundreds of years of colonialism. The structure of the world economy and trade patterns were still based on colonial past even though colonialism as political system had been dismantled. The infrastructures constructed in the colonized countries were made to serve the needs of the colonial powers. The entire world economy still served to enrich the former colonial powers, channelling resources and wealth from the South to the North and increasing international inequality. Development aid was not enough to turn the flow and stop the gap growing between the developing and the industrialized countries. A new international economic order was needed. In 1973 the oil producing developing countries, OPEC, took the power in their own hands which the control of oil resources afforded them. At one blow they tripled the oil price on the world market, causing an unprecedented crisis in industrialized world entirely dependent on oil. These countries were gripped with great anxiety and under those circumstances they approved the Declaration and Programme of Action for the New International Economic Order (NIEO), prepared and proposed by the Group 77 of developing countries at the sixth Special Session of the UN General Assembly in spring of 1974. It was a concrete plan for governing trade and world economy by decisions and agreements of governments together. The NIEO was approved unanimously. The NIEO was a global plan to reduce inequalities between the states. In 1976 the World Employment Conference adopted the Basic Needs Strategy aimed at reducing inequalities within the states. It resolved that meeting basic needs of the most vulnerable groups should be a priority of development policies in each country. People should have the right to participate in decisionmaking processes in order to secure that their needs will be taken into account. This is a precondition for the fulfilment of democracy. In a few years then during the 1970s the Member States of the UN approved three very comprehensive and substantial programmes unanimously: an Action Plan for the Human Environment, the NIEO and the Basic Needs Strategy. These programmes constitute a global strategy to govern international development. Furthermore, in those years also the importance of self-reliance in all development efforts nationally as well as collectively was strongly emphasized. The boom in the world economy created a favourable climate for these progressive decisions in the 1970s. The multilateral and bilateral development allocations increased every year in many countries. For developing countries it was easy to receive credits on favourable terms from international financial markets. In this climate business also believed that it was worth investing in developing countries. The situation in many developing countries improved visibly. The gap between the rich and poor continued to widen, but at a slower pace. At that time the scale of the problems was still somewhat reasonable helping to see the development efforts as being meaningful. If the approved programmes and plans had been effectively implemented right after the world situation today would be entirely different. Then the solution of 5 Figure 1. Graph: Hilkka Pietilä The New International Economic Order and the Basic Needs Strategy are development platforms adopted unanimously by the UN Member States in 1970s. Together with the self-reliance policies they would have made up a balanced over all strategy for local and global development. In the lower triangle I am suggesting the transformations, which should take place in the industrial countries in favour of more balanced development in general. _________ _ ______ __________ ______________________ the problems would have been much easier than now, when international inequality and environmental problems have deteriorated further all these years and neo-liberal policies in economy and trade have accelerated the pace of deterioration during additional twenty years. Faith and hope of just development This development in the 1970s generated enormous hope in the minds of those who had sought for effective means to improve the situation of developing countries and their position in the world economy. Also the significance of development aid was put in realistic frame within these plans as a whole. In my own activities and in the United Nations Association we channelled much of our efforts to publicizing and getting recognition to NIEO, the Basic Needs Strategy and self-reliance policies. We dealt with these themes in almost all the issues of our journal. The circulation of the bulletin was 10, 000 at that time and we sent free copies to all teachers of history, social science, geography and biology. Above all, we wanted to influence the Finnish government to work for these 6 programmes, as it had supported them in the UN. On my part I tried to show that also foreign trade and economic policies should be changed in all industrialised countries, including Finland, in order to make these programmes operational and realised in practice. In the late 1970s I made a syntheses of these three big international development programmes in a major article entitled, “The Basic Elements in Contemporary Development Thinking”. The attached chart on the basic pillars of harmonious development thinking is a summary of this syntheses. The content of the article was also included in a book published by the Institute of Development Studies, at the University of Helsinki, called the “Problems of the World’s Agriculture”, as well as in the handbook on international education produced by the UN Association called, “Our Common World”. The latter was intended as a first handbook for teachers to include international development issues and the activities of the UN into the school curriculum. Such a book had been awaited in schools for a long time. The first 1977 edition quickly sold out and a renewed and revised second edition was published in 1978. In 1984 the Finnish UN Association produced a book on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the UN, “Peace and Justice – 40 years of the UN”, the main focus of which were articles dealing with UN economic and social development. In this book the above-mentioned article on the basic development programmes was also published in extended and complemented form entitled “The UN as an Arena for Development Debate”. With the support of the foreign ministry the Finnish UN Association also published a booklet in 1985 on the operative work of the UN, entitled “UNDP – the Heart of Multilateral Development Co-operation”, in which the above mentioned article was included as well. The United Nations – the instrument for building a better world The United Nations is an institution founded to promote peace, security and democracy as well as human rights, justice and equity between people and nations in the world. These values and goals are explicitly written in the UN Charter and further clarified in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. However, the success of the UN in realising these values depends always on the political will of the governments of member states, as they express it in the UN resolutions and as they implement them in their own policies. My goal has been: - To advocate and support the values and ideals, which are the foundations of the UN and to participate in democratic functions in order to influence the policies of my own government. In co-operation with people and organisations here and in other countries that share the same ideas I have also participated in the efforts to influence government policies at the international level. My solidarity work over the years can be summarised as two kinds of efforts: - The efforts to study the issues profoundly in order to understand the causes of the problems and to review emerging new perspectives put forward as solutions to these problems, and also assessing these perspectives, from the point of view of how they would advance the wellbeing of people, international justice and an ecologically sustainable and healthy development in the world. - The efforts to disseminate and make known the kind of thinking, which according to my 7 judgement, would move the world towards a healthy direction, and to promote the sense of justice and understanding among people, as well as the motivation to act in their own lives, in politics and within the society with the best of their capability for the fulfilment of these goals. Even though governments in the UN approved the sensible and realistic programmes of the 1970s unanimously, their implementation became caught up with intergovernmental conflicts. In fact the interests of multinational corporations were already then strong forces behind the governments of many industrialised countries. The power of business corporations does not recognise democracy in any country, but can effectively force governments to support their own interests. Democratic governments are caught up between the will of the people and the demands of economic powers. There was still an attempt in the UN to keep these principles and efforts of 1970s alive by incorporating a large part of them in the Second Development Strategy designed for the 1980s. Then the NIEO and the Basic Needs Strategies had become taboo words and they were not used in that document but a lot of their basic substance was written in with other words. The World of globalizing Market Capitalism. For decades development analysts and experts have demanded changes in the policies and patterns of development in the North in order to give space for development in the South – in order that the North would not consume all too much of the limited natural resources of humankind and destroy the preconditions for improvement of the life of people in the South. This was the solidarity aimed at in the global development plans and strategies in the 1970s. In the 1980s the debt crisis of developing countries got out of hand to such an extent that even the positive achievements of the 1970s were lost in many countries and development started to decline. I spoke up for human dignity and basic needs, still. I maintained that the consumption patterns, life style as well as the economic policies in the North are the most serious problem for the whole world, and particularly to the countries and people in the South. I gave lectures and speeches on these themes frequently in the 1980s. I also dealt with these issues in my book “Ihmisen Puolustus” (In Defence of Human Dignity), published in 1981. Another book “Vallan Vaihto” (Transforming Power) of 1988 I started suggesting that in fact the current crisis in developing countries demonstrates the bankruptcy of western economic policies and thinking, the consequences of which have been turned upon the countries in the South. However, no broader discussion of this “white man’s burden” and responsibility got up in Finland. The support for movements promoting international justice, ecologically healthier life, recycling, and avoiding waste and pollution remained weak. However, there is quite a lot of people around these movements, who have lived ‘alternatively’ for decades and gained a lot of experience in different ways of life. Village people everywhere have a lot in common An exception is the village action movement that grew to become the largest popular movement in 8 Finland in those decades. This movement successfully waged a delay struggle to preserve traditional communities and a natural lifestyle in the Finnish countryside. The principles and goals of the village movement originally corresponded, to a great extent, to those visions and goals that the proponents of so-called alternative or sustainable development tried to advocate for the developing countries. However, the third world solidarity movement and the village action movement never were teaming up, even though both have been engaged in defence of people against the domination of destructive market culture. The more I learned about the village action movement, the more I felt close to it. I was born and raised in a Finnish village. I saw how people in the Finnish countryside sought rescue in their genuine traditions and culture in the same way as many people in the villages of the South in trying to fend off the steam-rolling market culture. In order to encourage these people and to get them international recognition – they were not recognised at home – I nominated the Village action movement in 1988 to the Right Livelihood Foundation for its annual award. After several years of attempts, the Finnish village action movement was honoured with the award called Alternative Nobel Prize in 1992 “for showing that there is a dynamic, life-enhancing alternative to the rural decline, centralisation and popular disempowerment that is the norm in Europe today”. When the representatives of the movement received their prize in the festive celebration in Stockholm 1992, it was one of the happiest moments in my life. Basic needs and social development revisited. The latest world-wide cry of distress for social development and basic needs was the UN World Summit for Social Development in Copenhagen in 1995. The initiators of this Conference were the same people and forces in the UN circles that in the 1970s had been the architects of the NIEO and the Basic Needs Strategy. They saw how globalizing market capitalism breaks down social structures in both the developing and industrialised countries and increases inequality between people and nations. The objective of the summit was to highlight the growing poverty in the midst of incredible waste and abundance and to get governments to pledge their commitment to strive for alleviating poverty and its eventual eradication. The Secretary General of the Summit, Juan Somavia, afterwards stated that the conference “was a profound emergency cry - and moral and ethical challenge to governments, business people, the mass media, trade unions, political parties, the intelligentsia and civil society in general and for all of us as individuals, to really prioritise social development on the very top of the list right now and for the 21st century”. However, the documents and the outcome of this conference speak of poverty eradication and helping the poor as if poverty was a single plaque that can be eradicated without intervening in the world economic structures and the goals of economic policies both in North and South. Such talk about poverty alleviation is hypocritical and false as long as Northern countries continue to aggravate poverty and inequality in the world and in the developing countries through their own trade and economic policies. Why oppose Finnish EU membership? 9 It was based on these same values that I opposed Finland’s membership in the European Union. I devoted all my strength and time to this campaign for over three years. Many asked why I was opposing the EU when I had worked, with full force, for many decades to promote international cooperation. It was easy to answer this question: “That is precisely why!” The internationalism of the UN and of the EU are two completely different issues, in fact they are opposed to each other. The internationalisation in the EU stands for market forces and harsh competition. It exploits international inequalities and does not even attempt to reduce them. An unequal world is a profitable business environment - for the time being! The paramount goal of the EU and EMU is to strengthen the competitive edge of European business against two other economic blocs. In that competition the funds for development co-operation with the South have already been reduced to half from the level of the 1980s. The scooping of oil and other non-renewable resources from the developing countries still accelerates for increasing production and consumption of people in rich economic blocs. Big corporations are effectively exploiting cheap labour and utilising low taxation, weak environmental standards and non-existent social security in the developing countries. In the so-called tax-free export processing zones big companies can benefit from the comparative advantage of absolute poverty without any burden of legal regulations and taxation. The ultimate causes of environmental destruction are poverty in the developing countries and affluence in the industrialised countries. When neo-liberal trade and economic policies help to widen this gap, environmental destruction increases on both sides. Business unscrupulously exploits this internationalization. European integration rests on this ideology. Many in the South have not without cause spoken of ‘Fortress Europe’ and return to colonization. The conflict between the internationalization of the UN and that of the market forces is the conflict between the interests of people and those of the capital. The old conflict between labour and capital has taken on a new form and is deeper than ever before. An utopia of a brave new Europe In my EU book in 1992 I also outlined the kind of Europe that would attempt at relieving and resolving the problems of humanity instead of worsening them. What kind of Europe would be part of the solution rather than the world’s biggest problem? Around the time of the fall of the Berlin Wall (1989) and before the final approval of Maastricht Treaty (1992) Europe would have had a historic opportunity to change its course. There was no longer a fear of threat and ideological competition from the East. If the strong, wealthy and enlightened Europe wanted to combine its unrivalled spiritual, intellectual, economic and political resources and direct them in a new way, it would have the potential to become a progressive, modern engine for the best interests of humanity that could turn development towards _ economically, socially and ecologically sustainable development in Europe and in the whole world, the kind of development that was called for among others in the UN Conference on the Environment and Development in the summer of 1992; 10 _ _ _ a balanced economy that is not aimed at increasing production and consumption but rather at securing the moderate welfare of the people in a state of declining production and trade in Europe; developing regulating mechanisms for international economy and trade in accordance with the guidelines sketched by the NIEO, so that developing countries would also have the options to develop their own economies and improve the life of their people; self-sufficiency and ecological sustainability in production for peoples’ basic needs in the North as well as in the South. On that basis Europe would become a positive alternative to the destructive economic models of the United States and Japan, and gradually _ the exploitation of natural resources in the industrialised countries would begin to decline, so that the amount of waste, pollution and the scale of environmental destruction would also be reduced; _ the gap between the rich and the poor countries would start to narrow, and the causes of war and crisis would decrease; _ the flow of immigrants and refugees would be stemmed since people would no longer have to escape their home countries due to war, poverty and hardships; _ the conditions for peaceful development would be improved in the world in general as well as between different countries and regions; _ Europe would not become the ‘Fortress of the Rich’ but rather borders in the EU could also be opened outwards and not just between member countries; _ it would facilitate international co-operation where all European countries could participate as equal independent partners; _ Europe would contribute constructively to a more balanced progress in the entire world. The rich, enlightened and strong Europe is the region in the world where such a complete change of course could have been expected. If a rich and strong Europe had refused to continue co-operation with other regions on the current terms, the others would have been forced to change their course, too. An active European support could have given the UN a radically different impetus to construct a decisive change in development of the whole world. Europe has however let this trial period to slip by. From quite a different point of departure, hopes could be pinned now on Africa since it has not yet come that far on this inverted path of development. If Africa would be let to conduct its development independently, it could still possibly have an option to choose differently. The decisions to restrain globalization would need to be taken at the global level. They can be taken only in the UN, provided governments would have the political will to do so. The other alternative in countervailing globalization is the civil disobedience of millions of citizens to the market: active and informed boycott of the values, incentives and temptations of the market by small communities, households and individual people in everyday life. That is something what all of us can do! Note: The books and publications mentioned in this article are published in Finnish. These thoughts and visions I have been dealing with also in various articles and papers in English. E-mail: hilkka.pietila@pp.inet.fi 11