Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

advertisement

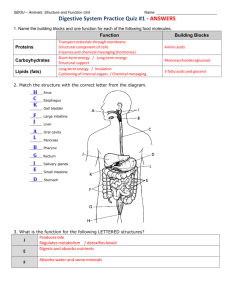

Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Volume 56 • Number 6 • December 2002 Copyright © 2002 American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy GI involvement in Henoch-Schönlein purpura Motohiro Esaki MD Takayuki Matsumoto MD Shotaro Nakamura MD Masumi Kawasaki MD Keiichiro Iwai MD Katsuya Hirakawa MD Ken-ichi Tarumi MD Takashi Yao MD Mitsuo Iida MD Received April 1, 2002. For revision June 5, 2002. Accepted July 7, 2002. Current affiliations: Departments of Medicine and Clinical Science and Anatomic Pathology, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Department of Endoscopic Diagnostics and Therapeutics, Kyushu University Hospital, Fukuoka, and Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Kawasaki Medical School, Okayama, Japan. Reprint requests: Motohiro Esaki, MD, Department of Medicine and Clinical Science, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Maidashi 3-1-1, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka 812-8582, Japan. Copyright © 2002 by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 0016-5107/2002/$35.00 + 0 37/1/129592 Background: The diagnosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura is difficult, especially when abdominal symptoms precede cutaneous lesions. The aim of this study was to determine the distribution of GI involvement in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Methods: Endoscopic or radiographic findings throughout the entire GI tract were retrospectively reviewed for 7 patients with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Histopathologic findings were analyzed and correlated with findings at EGD and colonoscopy. Observations: The duodenum and small intestine were most frequently involved (6 patients, each site). Contrast radiography of the small intestine demonstrated thickened mucosal folds or small barium flecks. Findings at EGD were multiple irregular ulcers, mucosal redness and petechiae in the duodenum. In 4 patients, the second part of the duodenum was predominantly affected. Ulcerating lesions accompanied by hematoma-like protrusions were detected in 4 patients in whom leukocytoclastic vasculitis was proven histopathologically. Conclusions: EGD appears to have the greatest diagnostic utility in patients suspected to have Henoch-Schönlein purpura with GI involvement. Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is a vasculitis of the small vessel of the skin, joints, GI tract, and kidney.[1] [2] GI symptoms occur in up to 85% of patients,[3] and GI involvement can manifest as severe problems such as intussusception,[4] obstruction,[5] and perforation. [6] Although such severe manifestations occasionally require surgical intervention, some patients in whom abdominal symptoms precede the typical skin rash may undergo unnecessary exploratory laparotomy. [7] Abdominal symptoms reportedly precede other manifestations in 14% of patients. [8] In this clinical circumstance, GI involvement may be a clue to the diagnosis of HSP. Mucosal lesions develop anywhere within the GI tract in patients with HSP. Diffuse mucosal redness, small ring-like petechiae and hemorrhagic erosions are characteristic endoscopic findings.[9] [11] Radiographically, mucosal thickening and filling defects have been described. [12] [13] Although the small intestine is considered to be the most frequently affected site, [12] [14] there are no studies in which the entire GI tract was systematically evaluated in a group of patients with HSP. In this study, GI involvement by HSP was retrospectively investigated in a group of patients whose GI tract was thoroughly examined endoscopically or radiographically. Histopathologic findings were also reviewed to identify endoscopic findings that contribute to the diagnosis of HSP. Patients and methods A diagnosis of HSP was made in 16 patients at our institution from 1986 to 2000 based on typical clinical features including a purpuric rash and histopathologic features in biopsy specimens obtained from involved skin. In 7 patients, the entire GI tract was endoscopically or radiographically examined during the acute phase of the disease. These patients were the subjects of the present investigation. There were 4 men and 3 women whose ages ranged from 13 to 64 years at the time of diagnosis. In 5 patients, abdominal symptoms occurred within 2 to 10 days after appearance of the purpuric skin rash. Abdominal symptoms preceded the typical skin rash in the remaining 2 patients (Table 1). Table 1. Summary of clinical characteristics and GI involvement in patients with HSP Duodenoscopic findings Histologic findings Age Symptoms Case (y)/gender at onset HematomaGI Mucosal Irregular like involvement edema/redness ulcer protursion LCV Extravasation of RBC ICI Visceral involvement Outcome 1 20/M Epigastralgia, Duodenum, arthralgia colon Moderate Multiple Present Present Marked Marked 2 52/F Purpura Duodenum, small intestine, colon Mild Multiple Present Present Moderate Moderate Kidney Continuing nephritis 3 13/M Abdominal pain, arthralgia Stomach, duodenum, small intestine, colon Mild Multiple None Absent Mild Kidney Continuing nephritis 4 64/M Purpura, arthralgia Stomach, duodenum, small intestine, colon Moderate Multiple Present Present Marked Marked Kidney, lung Deceased 5 23/F Purpura Duodenum, small intestine Marked Multiple Present Present Marked Marked None Improved 6 36/M Purpura Duodenum, small intestine Mild Multiple None Absent Absent Mild Kidney Continuing nephritis 7 43/F Purpura Small intestine None None None NE NE NE Kidney Improved Mild None L LCV, Leukocytoclastic vasculitis; RBC, red blood cell; ICI, inflammatory cells infiltration; NE, not examined. Abdominal symptoms included colicky pain in all patients, nausea and vomiting in 3, and melena in 2. Urinalysis or renal biopsy suggested the presence of nephritis in 5 patients. All patients were treated with corticosteroids (prednisolone, 40 to 60 mg/day); this was effective in 3, whereas nephritis persisted in 3 patients. One patient died of pulmonary hemorrhage and renal failure 5 months after diagnosis (Table 1). Endoscopy and radiography Improved GI examinations were performed within 2 to 12 days after the onset of abdominal symptoms. Preparation for colonoscopy was by ingestion of an oral electrolyte lavage solution. Small intestine radiography was by either barium meal follow-through or double-contrast technique. For the latter, 200 to 300 mL of 60% barium sulfate and a sufficient volume of air were introduced through a nasoduodenal tube. Biopsy findings At EGD and colonoscopy, biopsy specimens were obtained from the most severe mucosal lesion. Specimens were embedded in paraffin, cut into slices approximately 4 μm thick, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The small vessel vasculitis with infiltration by polymorphonuclear leukocytes, referred to as leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV), was regarded as the characteristic pathologic finding of HSP.[15] The following items were assessed for each biopsy by one pathologist (T.Y.) who was blinded to these clinical features: degree of red cell extravasation and inflammatory cell infiltration in mucosa and submucosa. Observations Endoscopic and radiographic findings Six patients had involvement of multiple sites within the GI tract (Table 1), the duodenum and small intestine being most frequently affected. EGD revealed duodenal mucosal lesions in 6 patients and gastric lesions in 2 patients. The esophagus was not involved in any patient. Multiple ulcerations in the gastric body or circumferential redness in the antrum was observed (each in 1 patient). The duodenal mucosal lesions extended to the second part of the duodenum in 6 patients (Table 1). Involvement in the second part was more severe than in the bulb in 4 patients. Although the degrees of mucosal redness, edema, and petechiae were variable, multiple irregular ulcers were uniformly found in the duodenum of the 6 patients (Fig. 1). Fig. 1. Endoscopic view of ulcerating lesion with darkreddish, hematoma-like protrusion in second part of duodenum (Case 2). In 4 patients with severe duodenal involvement, ulcers were accompanied by hematoma-like protrusions. Small intestinal radiography depicted mucosal abnormalities in 6 patients. Radiographic findings included thickened mucosal folds in all 6 patients (Fig. 2) and small barium flecks in 5. Fig. 2. Barium contrast radiograph of ileum showing markedly thickened mucosal folds with large filling defects (Case 3). In one patient, there were shallow ulcers in the ileum. Although such findings were widespread in 2 patients, small intestine involvement was restricted to the ileum in 4. Colonoscopy identified mucosal lesions in 4 patients. In 3, scattered areas of mucosal redness were found in the rectosigmoid colon. In the fourth patient, there was diffuse mucosal redness and numerous small ring-like petechiae in the left colon (Fig. 3). Fig. 3. Colonoscopic view showing diffuse mucosal redness and small ring-like petechiae in transverse colon (Case 3). Histopathologic findings In 4 patients, LCV was identified in duodenal biopsies (Fig. 4). Fig. 4. Photomicrograph of biopsy from duodenal lesion showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis with inflammatory cell infiltration (Case 2) (H&E, orig. mag. ×25). Inflammatory cell infiltration and red cell extravasation in the mucosa and submucosa were prominent in patients with LCV. All 4 patients had ulcerating lesions accompanied by hematoma-like protrusions in the duodenum (Table 1). LCV was identified in colonic biopsy specimens from one patient who had diffuse mucosal redness and small ring-like petechiae. Specimens obtained from the other 3 patients disclosed nonspecific inflammation with lymphocytic infiltration. Discussion Abdominal symptoms due to HSP include colicky pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, and vomiting. [16] In one series, exploratory laparotomy was performed because of severe complications in 10% of patients with abdominal symptoms.[4] Although HSP is less frequent in adults than children, the age of onset ranges from 6 months to adulthood.[17] Moreover, there have been patients with abdominal manifestations in whom the typical skin rash was lacking at onset. [8] GI manifestations in the acute phase of the disease should thus be noted, even in adults. Although the small intestine is thought to be the most frequent site affected, [12] [14] GI involvement in HSP has not been systematically investigated to date. In the present study, GI involvement was analyzed in 7 patients whose GI tract was thoroughly examined during the acute phase of the disease. The results indicate that the duodenum and small intestine are the most frequently involved sites. The duodenoscopic findings described in HSP are diffuse mucosal redness, small ring-like petechiae and hemorrhagic erosions.[9] [10] [18] [20] In another study, the second part of the duodenum was found to be predominantly affected. [21] In the present investigation, multiple irregular ulcers were found in all patients with duodenal involvement. In addition, ulcerations accompanied by hematoma-like protrusions were identified in 4 patients. However, other duodenoscopic findings, such as mucosal redness and edema, varied from patient to patient. As has been reported, [21] duodenal involvement was more prominent in the second part of the duodenum than in the bulb. It thus seems likely that multiple irregular ulcers in the second part of the duodenum are characteristic of duodenal involvement in HSP. Although such duodenal lesions are comparatively rare,[22] eosinophilic enteritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Crohn's disease, and parasitic infection are other conditions to be considered in a differential diagnosis.[23] Biopsies may help to differentiate HSP from these diseases. In the present study, LCV was found in patients with ulcerating lesions accompanied by hematoma-like protrusions. Because the frequency of LCV in biopsies correlates with the severity of duodenitis, [14] and because red blood cell extravasation was prominent in specimens positive for LCV, the hematoma-like protrusion seems to represent intramucosal hemorrhage due to vasculitis. Small intestine and colorectal involvement were also detected in our patients. As has been described,[12] [13] both thickened mucosal folds and small barium flecks noted by small intestine radiography, and patchy mucosal redness and small ring-like petechiae at colonoscopy were documented in our patients. However, when considering the preparation required and complexity of the several procedures, together with accuracy of biopsy findings, duodenoscopy seems to be the procedure of choice when HSP is suspected in patients with GI symptoms. References 1. Ilona SS. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1994;6:25-31. Abstract 2. Ricardo B, Victor MMT, Yicente RV, Miguel GF, Miguel AGC. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adulthood and childhood. Am Coll Rheumatol 1997;40:859-64. 3. Ilona SS. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: when and how to treat. J Rheumatol 1996;23:1661-5. Abstract 4. Martinez-Frontanilla LA, Haase GM, Ernster JA, Bailey WC. Surgical complications in Henoch-Schonlein purpura. J Pediatr Surg 1984;19:434-6. Abstract 5. Clark CV, Hunter JA. Anaphylactoid purpura presenting as a medical and surgical emergency. Br Med J 1983;287:22-3. Citation 6. Okano M, Suzuki T, Takayasu H, Harasawa S, Sato T, Tsutsumi Y, et al. Anaphylactoid purpura with intestinal perforation: report of a case and review of the Japanese literature. Pathol Int 1994;44:303-8. Abstract 7. Cream JJ, Gumpel JM, Peachey RDG. Schönlein-Henoch purpura in adults. Q J Med 1970;39:461-83. Citation 8. Lanzkowsky S, Lanzkowsky L, Lanzkowsky P. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Pediatr Rev 1992;13:130-7. Citation 9. Tomomasa T, Hsu JY, Itoh K, Kuroume T. Endoscopic findings in pediatric patients with Henoch-Schönlein purpura and gastrointestinal symptoms. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1987;6:725-9. Abstract 10. Banerjee B, Rashid S. Singh E, Fitzgerald J. Endoscopic findings in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Gastrointest Endosc 1991;37:569-71. Citation 11. Yoshikawa N, Yamamura F, Akita Y, Sato T, Mitamura K. Gastrointestinal lesions in an adult patient with HenochSchönlein purpura. Hepatogastroenterology 1999;46:2823-4. Abstract 12. Rodriguez-Erdmann F, Levitan R. Gastrointestinal and roentogenological manifestations of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Gastroenterology 1968;54:260-4. Citation 13. Kawasaki M, Hizawa K, Aoyagi K, Kuroki F, Nakahara T, Sakamoto K, et al. Ileitis caused by Henoch-Schönlein purpura; an endoscopic view of the terminal ileum. J Clin Gastroenterol 1997;25:396-8. Citation 14. Sakagami S, Noda H, Koshino Y, Shinpo M, Chiyo H, Yamazaki T, et al. Gastrointestinal tract lesions in a case of Schönlein-Henoch purpura associated with melena and review of 32 cases in Japan (Japanese). Gastroenterol Endosc 1988;30:1250-4. 15. Mills JA, Michel BA, Bloch DA, Calabrese LH, Hunder CG, Arend WP, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:1114-21. Abstract 16. Fauci AS, Haynes BF, Katz P. Spectrum of vasculitis. Ann Intern Med 1978;89:660-76. Abstract 17. Tizard EJ. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Arch Dis Child 1999;80:380-3. Citation 18. Goldman LP, Lindenberg RL. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: gastrointestinal manifestations with endoscopic correlation. Am J Gastroenterol 1981;75:357-62. Citation 19. Cappell MS, Galpta MA. Colonic lesions associated with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Am J Gastroenterol 1990;85:11868. Abstract 20. Akdamar K, Agawal NM, Varela PY. The endoscopic appearance of anaphylactoid purpura. Gastrointest Endosc 1973;20:68-9. Citation 21. Kato S, Shibuya H, Naganuma H, Nakagawa H. Gastrointestinal endoscopy in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Eur J Pediatr 1992;151:482-4. Abstract 22. Takasu S, Nagumo K, Harada Y, Yamazaki T, Notsumata K, Ito S, et al. Duodenitis observed in routine panendoscopy; spectrum of duodenitis in Japanese (Japanese). Stomach Intest 1989;24:1241-9. 23. Heatley RV, Wyatt JI. Gastritis and duodenitis. In: Haubrich WS, Schaffner F, Berk JE, editors. Bockus gastroenterology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995. p. 635-55.