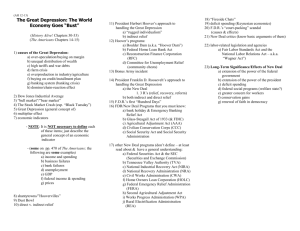

Emergency relief handbook - Department of Human Services

advertisement