Technology Education: Proposed changes and why

advertisement

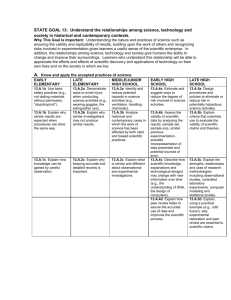

Technology Education: Proposed changes and why July 2005 Overview The three strands in Technology in the New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 1995) are ‘Technological Knowledge and Understanding’, ‘Technological Capability’, and ‘Technology and Society’. Within current technology programmes these three strands are integrated to support students as they undertake technological practice. As a result of 10 years of classroom practice and on-going educational researchi understanding in technology education has evolved. A key finding from this research was the importance of students undertaking technological practice. To support this and allow students to achieve the aim of technology education, which is to develop students’ technological literacy, the following changes have been recommended: The three strands are redefined as ‘Nature of Technology’ii ‘Technological Knowledge’iii and ‘Technological Practice’. Achievement objectives have been identified to support the three strands and indicators of progression are identified. Technological areas and contexts have not been stipulated. Reasons for changes The strands The current curriculum is focused on developing technological practice through the integration of the three strands. This integration is now represented in the draft essence statement as a single strand named technological practice. The importance of understanding the nature of technology has been recognised by being given a strand in its own right. While knowledge gained through technological practice is an essential part of technological literacy, the new curriculum structure recognises that technological knowledge can also be gained in other ways. This recognition is expressed in the updated technological knowledge strand which refers to knowledge that is developed and can be expressed outside of practice. The inclusion of the nature of technology and the technological knowledge strand allows the opportunity for learners to study aspects of technology in ways other than through their own practice. Achievement objectives Research on teachers’ classroom programmes has resulted in a matrix of indicators of progression for technological practice. These have been focused on three achievement objectives which are; undertake brief development, undertake planning to support and inform practice and develop and evaluate technological outcomes. In addition current research is exploring the nature of technology and technological knowledge. This research involves talking to technologists and trialling these findings in the classroom. The findings from this research will inform the development of the achievement objective and indicators of progression for the remaining two strands. Rationale – Technology Education: Proposed changes and why, July 2005 Page 1 of 3 Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/whats_happening/technology_e.php © New Zealand Ministry of Education 2005 – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Areas/contexts The current curriculum names technological areas and contexts. However the essence statement does not identify any areas or contexts in recognition of the restrictive nature of doing this. Classroom practice and research has clearly shown that learning in technology often goes across a number of technological areas and contexts and beyond those named. Implications for programme design A technologically literate student should be able to engage in technological practice, develop their technological knowledge and critique technological achievements and issues. The aim of technological literacy requires this exploration from a wider perspective than students’ own technological practice. Therefore technology units may now be situated within a strand or a variety of combinations in order to enrich the programme. However all strands must be comprehensively covered and integrated within an overall programme in technology education. The removal of the restriction of named technological areas and contexts will allow schools to develop programmes that reflect their unique communities. A consequence of these changes means that the potential for diversity in technology education is increased. i Examples of national and internationally published research on technological education include: Burns, J. (1997) Technology-Intervening in the World. In J. Burns (Ed.). Technology in the New Zealand Curriculum-Perspectives on Practice. Palmerston North: The Dunmore Press. pp.1–30. Compton, V.J. & Harwood, C.D. (2004). Moving from the one-off: Supporting progression in technology., set: Research Information for Teachers, 1, 23–30. Compton, V.J., & Harwood, C. D. (2003) Enhancing Technological Practice: An assessment framework for technology education in New Zealand. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 13(1), 1–26. Compton, V.J. & Jones, A.J. (2003, October) Visionary Practice or Curriculum Imposition?: Why it matters for implementation. Published in conference proceedings of Technology Education New Zealand, Biannual conference, Hamilton. Davies Burns, J. (2000) Learning about technology in society: developing a liberating literacy. In J. Ziman (Ed.), Technological Innovation as an Evolutionary Process. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. pp. 299-311. France, B. (1999). Technological Literacy: A realisable goal or a chimera? ACE Papers. Issue 5 December 1999 pp 38–52. Jones, A. (2003) The development of a National Curriculum in technology for New Zealand International Journal of technology and design education, 13, 83–99. Jones, A., & Moreland, J. (2003) Developing classroom-focused research in technology education. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education 51-66. Rationale – Technology Education: Proposed changes and why, July 2005 Page 2 of 3 Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/whats_happening/technology_e.php © New Zealand Ministry of Education 2005 – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector Moreland, J. & Jones, A. (2000). Emerging assessment practices in an emergent curriculum: Implications for technology. International Journal of Technology and Design Education,10(3), 283–305. Moreland, J., Jones, A., & Northover, A. (2001). Enhancing teachers' technological and assessment practices to enhance student learning in technology: A two year classroom study. Research in Science Education,31(1), 155-176. Milne, L. (2004). Put your finger on your nose if you are proud of your technology: Technology in the new entrant classroom. set: Research Information for Teachers, 1, 31–36. Moreland, J. (2004). Putting students at the centre: Developing effective learners in primary technology classrooms. set: Research Information for Teachers, 1, 37–43. Petrina, S. (2000). The Political Ecology of Design and Technology Education: an inquiry into methods. International Journal of Technology and Design Education 10, 207–237. ii For detailed information see the briefing paper: Compton V. J. (2004) Technological knowledge: A developing framework for technology education in New Zealand. Briefing Paper prepared for the New Zealand Ministry of Education Curriculum Marautanga Project. iii For detailed information see the briefing paper. Compton, V. J. & Jones, A. (2004).The Nature of Technology: Briefing Paper prepared for the New Zealand Ministry of Education Curriculum Project Rationale – Technology Education: Proposed changes and why, July 2005 Page 3 of 3 Accessed from http://www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/whats_happening/technology_e.php © New Zealand Ministry of Education 2005 – copying restricted to use by New Zealand education sector