Change Leadership

advertisement

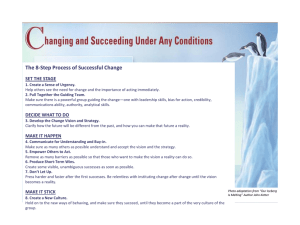

Winning at Change by John P. Kotter Leader to Leader, No. 10 Fall organization today -- large or small, local or global -- is immune to change. To cope with new technological, competitive, and demographic forces, leaders in every sector have sought to fundamentally alter the way their organizations do business. These change efforts have paraded under many banners -- total quality management, reengineering, restructuring, mergers and acquisitions, turnarounds. O Yet according to most assessments, few of these efforts accomplish their goals. Fewer than 15 of the 100 or more companies I have studied have successfully transformed themselves. The particulars of every case vary, but I have found that the change process involves eight critical stages (see box). Mismanaging any one of these steps can undermine an otherwise well conceived vision, but four mistakes in particular are the source of most failures. Thought Leaders Forum: John P. Kotter John P. Kotter is Konosuke Matsushita Professor of Leadership at Harvard Business School and a frequent speaker at top management meetings around the world. He is the author of six best-selling books, including Leading Change and A Force for Change: Leadership Differs from Management. His most recent is Matsushita Leadership. (9/98) 1. Writing a memo instead of lighting a fire. At least half More on John P. Kotter of failed change efforts bungle the first critical step establishing a sense of urgency. Too often leaders This article is Chapter launch their initiatives by calling a meeting or 9 in Leader circulating a consultant's report, then expect people to to Leader. rally to the cause. It doesn't happen that way. To See the complete increase urgency, I suggest you gather a key group of contents. people for a day-long retreat. First, identify every possible factor that contributes to complacency. If you From Leader to Leader, No. 10 Fall 1998 work at it, you will come up with 25 to 50. Then brainstorm specific ways to counter each factor. • Table of Finally, develop an action plan to implement your Contents • From the ideas. If you attack all 25 or 50 items, your chances of Editors creating a sense of urgency -- and building necessary • Resources momentum -- improve immeasurably. However, the effort involved in creating a sense of urgency is usually several times what leaders expect. They slide Additional resources for through this first crucial step, and when the effort stalls this article six months later, they wonder why. 2. Talking too much and saying too little. Most leaders undercommunicate their change vision by a factor of 10. And the efforts they do make to convey their message are of the least convincing variety -- speeches and memos. An effective change vision must include not just new strategies and structures but also new, aligned behaviors on the part of senior executives. Leading by example means just that -- spending dramatically more time with customers, cutting wasteful spending in the executive suite, or pulling the plug on a pet project that doesn't measure up. People watch their bosses -- particularly their immediate bosses -very closely. It doesn't take much in the way of inconsistent behavior by a manager to fuel the cynicism and frustration of his or her direct reports. 3. Declaring victory before the war is over. When a project is completed or an initial goal met, it is tempting to congratulate all involved and proclaim the advent of a new era. While it is important to celebrate results along the way, kidding yourself or others about the difficulty and duration of organizational transformation can be catastrophic. I met recently with a capable, intelligent management group that has begun to see encouraging results in a difficult initiative. They are only six months into what is probably a three-year process -- but are already talking about "wrapping this thing up in a few months." Such talk is nonsense. They are far from where they need to be, and in danger of losing the ground they have gained. People look forward to completion of any task. The problem is, the results of a change vision are not directly proportional to the effort invested. That is, one-third of your way into a change process, you are unlikely to see one-third of the possible results; you may see only 1/10th of the possible results. If you settle for too little too soon, you will probably lose it all. Celebrating incremental improvements is a great way to mark progress and sustain commitment -- but don't forget how much work is still to come. 4. Looking for villains in all the wrong places. The perception that large organizations are filled with recalcitrant middle managers who resist all change is not only unfair but untrue. In professional service organizations, and in most organizations with an educated workforce, people at every level are engaged in change processes. Often it's the middle level that brings issues to the attention of senior executives. In fact, I have found that the biggest obstacles to change are not middle managers but, more often, those who work just a level or two below the CEO -- vice presidents, directors, general managers, and others who haven't yet made it to "the top" and may have the most to lose in a change. That's why it is crucial to build a guiding coalition that represents all levels of the organization. People often hear the president or CEO cheerleading a change and promising exciting new opportunities. Most people in the middle want to believe that; too often their managers give them reasons not to. These common mistakes suggest three key tasks for change leaders: managing multiple time lines, building coalitions, and creating a vision. Managing Multiple Time Lines establish a sense of urgency and avoid declaring premature victory leaders must manage a key strategic resource -- time. Responding quickly while also accepting the long-term nature of the change process sounds like a paradox. But effective leaders make O it clear that meaningful change takes years. At the same time, they create shorter term wins and continuously remind people that the need for change is urgent precisely because it takes so long. When, for example, Konosuke Matsushita started the Matsushita Institute of Government and Management -- his graduate school for people who want to go into public service -- he explained that his vision was to help Japanese politics become less corrupt and more visionary. When a skeptical reporter asked how long that would take, he said, "In my judgment, about 400 years -- which is why it's so important that we start today." The best leaders that I have known balance short-term results with long-term vision. (When it comes to organizational change, I define short-term as six to 12 months.) They engage directors, investors, employees, and other constituents in the excitement of delivering both long- and short-term results. They operate in multiple time frames. Results and vision can be plotted on a matrix that has four dimensions (see figure). Poor results and weak vision spell sure trouble for any organization. Good short-term results with a weak vision satisfy many organizations -- for awhile. A compelling vision that produces few results usually is abandoned. Only good short-term results with an effective, aligned vision offer a high probability of sustained success. Some leaders fear they have too little time to manage long-term change and therefore focus only on quarterly or annual results. Yet many now reach senior leadership positions at age 50 or younger and have an opportunity to lead a number of transformations necessary to long-term leadership. Jack Welch, for instance, has led at least three major change visions at GE. Of course, he had the benefit of starting early and keeping his job a long time -- but he has kept the job precisely because he made organizational change an ongoing, multiphase process. Transforming an organization is the ultimate test of leadership, but understanding the change process is essential to many aspects of a leader's job. Two skills in particular -building coalitions and creating a vision -- are especially relevant to our times. Building Coalitions today's less hierarchical but more complex organizations, leaders must win the support of employees, partners, investors, and regulators for many types of initiatives. Because you are likely to meet resistance from unexpected quarters, building a strong guiding coalition is essential. There are three keys to creating such alliances. N Engaging the right talent. Coalition building is not simply reaching out to whoever happens to be "in charge" of a department, organization, or other constituency; it is assembling the necessary skills, experience, and chemistry as well. A coalition of 20 people who are decent managers but ineffective leaders is unlikely to create meaningful change -- or much else that is new. You don't necessarily start with the president or CEO as your partner; it may be the executive vice president who brings more to the party, and yet still connects you to the line organization. The most effective partners usually have strong position power, broad experience, high credibility, and real leadership skill. Growing the coalition strategically. Like a good board of directors, an effective guiding coalition needs a diversity of views and voices. Once a core group coalesces, the challenge is how to expand the scope and complexity of the coalition. It often means working with people outside your organization -- even for an internal change effort. Leaders must not only reach beyond the confines of their enterprise but also know where and how to build support. That may mean, for instance, giving others credit for success, but accepting blame for failures oneself. It means showing a genuine care for individuals but a toughmindedness about results -- getting results being the best way to recruit allies. Working as a team, not just a collection of individuals. Leaders often say they have a team when in fact they have a committee or a small hierarchy. The more you do to support team performance, the healthier will be the guiding coalition and the more able it will be to achieve its goals. Especially during the stress of change, leaders throughout the enterprise need to draw on reserves of energy, expertise, and, most of all, trust. Personnel problems often lurking beneath the surface of a team -- all too easily ignored during placid times -- come to the fore during times of change. The pressures of transformation make a strong team essential. Beyond the customary team-building retreats and events, real teams are built by doing real work together, sharing a vision, and commitment to a goal. Creating a Vision by example is essential to communicating a vision. But A vision of the future is more emotional than how do you actually build a vision? Because it relates to the rational. future, people assume that vision building should resemble the long-term planning process: design, organize, implement. I have never seen it work that way. Defining a vision of the future does not happen according to a timetable or flowchart. It is more emotional than rational. It demands a tolerance for messiness, ambiguity, and setbacks, an acceptance of the half-step back that usually accompanies every step forward. EADING Day-to-day demands inevitably pull people in different directions. Conflict is inevitable. Having a shared vision does not eliminate tension between, say, sales and manufacturing groups, but it does help people make appropriate trade-offs. The alternative is to bog down in I-win, you-lose fights that can paralyze an organization. Thus, leaders must convey a vision of the future that is clear in intention, appealing to stakeholders, and ambitious yet attainable. Effective visions are focused enough to guide decision making yet are flexible enough to accommodate individual initiative and changing circumstances. For example, this narrowly defined but effective change vision was developed by the operations group of a financial services company: "We want to reduce our costs by 30 percent and increase the speed with which we respond to customers by 40 percent. When this is completed, in approximately three years, we will have ... better satisfied customers, increased revenue growth, more job security, and the enormous pride that comes from great accomplishment." Traits of Effective Leaders exist at all levels of an organization. At the edges of the enterprise, of course, leaders are accountable for less territory. Their vision may sound more basic; the number of people to motivate may be two. But they perform the same leadership role as their more senior counterparts. They excel at seeing things through fresh eyes and at challenging the status quo. They are energetic and seem able to run through, or around, obstacles. EADERS I have found that people who provide great leadership are also deeply interested in a cause or discipline related to their professional arena. A leader in a pharmaceutical firm, for example, might have a passion for reducing suffering. He or she may have watched a parent or loved one suffer, and be motivated by deep emotions, not just intellect. Such leaders also tap deep convictions of others and connect those feelings to the purpose of the organization; they show the meaning of people's everyday work to that larger purpose. However, the most notable trait of great leaders, certainly of great Great leaders continue to take risks. change leaders, is their quest for learning. They show an exceptional willingness to push themselves out of their own comfort zones, even after they have achieved a great deal. They continue to take risks, even when there is no obvious reason for them to do so. And they are open to people and ideas, even at a time in life when they might reasonably think -- because of their successes -- that they know everything. Often they are driven by goals or ideals that are bigger than what any individual can accomplish, and that gap is an engine pushing them toward continuous learning. Leaders invest tremendous talent, energy, and caring in their change efforts, yet few see the results they had hoped for. But there is a good reason why so few organizations have transformed themselves. Today's leaders simply don't have much practice at large-scale change. Thirty years ago few organizations were thinking about radical reinvention, so there is little practical experience to be passed on to a new generation of managers. The good news is, the percentages are bound to improve. The kinds of changes routinely undertaken by today's organizations -- producing ever better products, more quickly, at ever lower cost -- were unimaginable 30 years ago. Over the next decade, thousands of leaders will guide equally remarkable changes. That is more than a safe prediction; it is a social and economic necessity. All institutions need effective leadership, but nowhere is the need greater than in the organization seeking to transform itself. Eight Steps to Transform Your Organization 1. Establish a Sense of Urgency Examine market and competitive realities Identify and discuss crises, potential crises, or major opportunities 2. Form a Powerful Guiding Coalition Assemble a group with enough power to lead the change effort Encourage the group to work as a team 3. Create a Vision Create a vision to help direct the change effort Develop strategies for achieving that vision 4. Communicate the Vision Use every vehicle possible to communicate the new vision and strategies Teach new behaviors by the example of the guiding coalition 5. Empower Others to Act on the Vision Get rid of obstacles to change Change systems or structures that seriously undermine the vision Encourage risk taking and nontraditional ideas, activities, and actions 6. Plan for and Create Short-Term Wins Plan for visible performance improvements Creating those improvements Recognize and reward employees involved in the improvements 7. Consolidate Improvements and Produce Still More Change Use increased credibility to change systems, structures, and policies that don't fit the vision Hire, promote, and develop employees who can implement the vision Reinvigorate the process with new projects, themes, and change agents 8. Institutionalize New Approaches Articulate the connections between the new behaviors and organizational success Develop the means to ensure leadership development and succession Return to reference The Ways Change Happens Organizations change of necessity and for a variety of reasons. But the single biggest impetus for change in an organization tends to be a new manager in a key job. These change leaders range from the middle to the top of an organization; it is often a new division-level manager or a new department head -- someone with fresh perspective -who sees that the status quo is unacceptable. While there is no single source of change, there is a clear pattern to the reasons for failure. Most often, it is a leader's attempt to shortcut a critical phase of the change process. Certainly, there is room for flexibility in the eight steps that underlie successful change -- but not a lot of room. When people say, for instance, "We're going to empower employees to act entrepreneurially -- but we don't need to spend a lot of time changing our whole organization," they are almost bound to fail. Producing change is about 80 percent leadership -- establishing direction, aligning, motivating, and inspiring people -- and about 20 percent management -- planning, budgeting, organizing, and problem solving. Unfortunately, in most of the change efforts I have studied in the past 20 years, those percentages are reversed. Our business schools and work organizations continue to produce great managers; we need to do as well at developing great leaders. Copyright © 1998 by John P. Kotter. Reprinted with permission from Leader to Leader, a publication of the Leader to Leader Institute and Jossey-Bass. Print citation: Kotter, John P. "Winning at Change" Leader to Leader. 10 (Fall 1998): 27-33. This article is available on the Leader to Leader Institute Web site, http://leadertoleader.org/leaderbooks/L2L/fall98/kotter.html. Permission to copy: Send a fax (+1-201-748-6008) or letter to John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Permissions Department, 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030 USA. Or online at http://www.wiley.com/about/permissions/. Include: (1) The publication title, author(s) or editor(s), and pages you'd like to reprint; (2) Where you will be using the material, in the classroom, as part of a workshop, for a book, etc.; (3) When you will be using the material; (4) The number of copies you wish to make. To subscribe to Leader to Leader: Call +1-888-378-2537 (or +1-415-433-1740) and mention priority code W02DF or see additional options at http://leadertoleader.org/leaderbooks/L2L/subscriptions.html. John Kotter (who teaches Leadership at Harvard Business School) has made it his business to study both success and failure in change initiatives in business. "The most general lesson to be learned from the more successful cases is that the change process goes through a series of phases that, in total, usually require a considerable length of time. Skipping steps creates only the illusion of speed and never produces satisfactory results" and "making critical mistakes in any of the phases can have a devastating impact, slowing momentum and negating hard-won gains". Kotter summarizes the eight phases as follows. 1] Establish a Sense of Urgency Talk of change typically begins with some people noticing a vulnerability in the organization. The threat of losing ground in some way sparks these people into action, and they in turn try to communicate that sense of urgency to others. In congregations it is typically membership loss, financial struggles or turnover in key volunteers and leaders. Kotter notes that over half the companies he has observed have never been able to create enough urgency to prompt action. "Without motivation, people won’t help and the effort goes nowhere…. Executives underestimate how hard it can be to drive people out of their comfort zones". In the more successful cases the leadership group facilitates a frank discussion of potentially unpleasant facts: about the new competition, flat earnings, decreasing market share, or other relevant indicators. It is helpful to use outsiders (say, for us, to bring in consultants, the unchurched, people from other denominations, regional or national staff people) who can share the "big picture" from a different perspective and help broaden the awareness of your members. When is the urgency level high enough? Kotter suggests it is when 75% of your leadership is honestly convinced that business as usual is no longer an acceptable plan. 2] Form a Powerful Guiding Coalition Change efforts often start with just one or two people, and should grow continually to include more and more who believe the changes are necessary. The need in this phase is to gather a large enough initial core of believers. This initial group should be pretty powerful in terms of the roles they hold in the church, the reputations they have, the skills they bring and the relationships they have. Regardless of size of your organization, the "guiding coalition" for change needs to have 3-5 people leading the effort. This group, in turn, helps bring others on board with the new ideas. The building of this coalition – their sense of urgency, their sense of what’s happening and what’s needed – is crucial. Involving respected leaders from key areas of your church in this coalition will pay great dividends later. 3] Create a Vision Successful transformation rests on "a picture of the future that is relatively easy to communicate and appeals to customers, stockholders, and employees. A vision helps clarify the direction in which an organization needs to move". The vision functions in many different ways: it helps spark motivation, it helps keep all the projects and changes aligned, it provides a filter to evaluate how the organization is doing, and it provides a rationale for the changes the organization will have to weather. "A useful rule of thumb: if you can’t communicate the vision to someone in five minutes or less and get a reaction that signifies both understanding and interest, you are not yet done with this phase of the transformation process". 4] Communicate that Vision Kotter suggests the leadership should estimate how much communication of the vision is needed, and then multiply that effort by a factor of ten. Do not limit it to one congregational meeting, a sermon by the minister, or a couple of mailouts to members. Leaders must be seen "walking the talk" – another form of communication -- if people are going to perceive the effort as important. "Deeds" along with "words" are powerful communicators of the new ways. The bottom line is that a transformation effort will fail unless most of the members understand, appreciate, commit and try to make the effort happen. The guiding principle is simple: use every existing communication channel and opportunity. 5] Empower Others to Act on the Vision This entails several different actions. Allow people in the church to start living out the new ways and to make changes in their areas of involvement. Allocate budget money to the new initiative. Carve out time on the Session agenda to talk about it. Change the way your church is organized to put people where the effort needs to be. Free up key people from existing responsibilities so they can concentrate on the new effort. In short, remove any obstacles there may be to getting on with the change. Nothing is more frustrating than believing in the change but then not having the time, money, help, or support needed to effect it. You can’t get rid of all the obstacles, but the biggest ones need to be dealt with. 6] Plan for and Create Short-Term Wins Since real transformation takes time, the loss of momentum and the onset of disappointment are real factors. Most people won’t go on a long march for change unless they begin to see compelling evidence that their efforts are bearing fruit. In successful transformation, leaders actively plan and achieve some short term gains which people will be able to see and celebrate. This provides proof to the church that their efforts are working, and adds to the motivation to keep the effort going. "When it becomes clear to people that major change will take a long time, urgency levels can drop. Commitments to produce short-term wins help keep the urgency level up and force detailed analytical thinking that can clarify or revise visions". 7] Consolidate Improvements and Keep the Momentum for Change Moving As Kotter warns, "Do not declare victory too soon". Until changes sink deeply into a church’s culture -- a process that can take five to ten years -- new approaches are fragile and subject to regression. Again, a premature declaration of victory kills momentum, allowing the powerful forces of tradition to regain ground. Leaders of successful efforts use the feeling of victory as the motivation to delve more deeply into their organization: to explore changes in the basic culture, to expose the systems relationships of the organization which need tuning, to move people committed to the new ways into key roles. Leaders of change must go into the process believing that their efforts will take years. 8] Institutionalize the New Approaches In the final analysis, change sticks when it becomes "the way we do things around here", when it seeps into the bloodstream of the corporate body. "Until new behaviours are rooted in social norms and shared values, they are subject to degradations as soon as the pressure for change is removed". Two factors are particularly important for doing this. First, a conscious attempt to show people how the new approaches, behaviours, and attitudes have helped improve the life of the church. People have to be helped to make the connections between the effort and the outcome. The second is to ensure that the next generation of congregational leaders believe in and embody the new ways. Kotter writes, "there are still more mistakes that people make, but these eight are the big ones. In reality, even successful change efforts are messy and full of surprises". Bibliography: You can go further into Kotter’s ideas by reading one of the following: The Article: "Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail" by John Kotter. Harvard Business Review, March-April 1995.