WILDLIFE 365 ORNITHOLOGY - Humboldt State University

advertisement

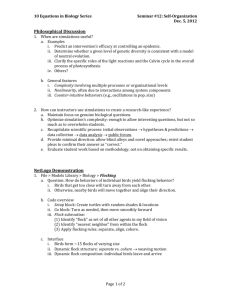

1 Matt Johnson Lecture Notes ORNITHOLOGY (Humboldt State Univ. WILDLIFE 365) LECTURE 22 – SOCIAL BEHAVIOR I. II. Intro – birds are both predators and prey. Their needs for food and for protection thus determine whether they are social or asocial, cooperative or competitive. This lecture focuses on these patterns, and we’ll conclude by examining and learning from our “bird bow” experiment last week. Territoriality. Territoriality and flocking are both conspicuous elements of avian life, and are well-studied. Spacing patterns are indeed better studied in birds than in any other animals. A. Definition – a territory is a given area that is defended for some period of time, although that may be for very short period of time. Use of this area by other birds is discouraged with acts of display or defense. Thus, primary (often exclusive) use of the area is limited to the defending individual (and in some cases its family or cooperative group members). B. Territoriality is not fixed, it is very flexible in time and space (example of Great Tits abandoning terr. in cold weather, and sanderling defending a moving Willet). C. General patterns 1. Territoriality overall is favored at moderate levels of food availability (we talked about this when we discussed food availability) 2. As territory size increases, the costs to defend it rise in proportion to its perimeter (2r), while the benefits rise in proportion to its area (r2). [Note, the benefits are in relation to need…so they do not increase without limit…they follow a logistic, or sigmoid, type of curve; thanks for the question Stein]. Thus, defensible territories are moderate in size. 3. Over the defensible range, territory size is further influenced by food availability in the environment, the less food available, the larger the territory. D. Dominance. Territoriality is one expression of dominance behavior. Dominant birds are better able to defend territories than are subordinate birds. 1. Dominance status is directly related to age and body size (sex only to some extent). Generally, larger birds (males in songbirds and many waterfowl, females in raptors and 2 III. shorebirds) dominate smaller birds, older birds dominate younger birds. 2. In polyandrous birds, females dominate. In polygynous birds, males dominate, in monogamaous…not so clear…but in some cases males dominate probably because these “monogamous” systems are more polygynous than we first thought. 3. Remember, must be careful with term “dominance.” We mean more likely to “win” behavioral interactions…more likely to pass on genetic material to future generations. This does not necessarily mean “better”, for environments are always changing. Just like ol’ Bobby Dylan sings, “the loser now will be later to win” 4. Rank has its advantages. a. Dominant birds defend the best territories, which can confer survival and/or reproductive advantages. b. Where territorial behavior is lacking, dominant birds get first access to preferred resources (food, mates, cover). c. When in flocks, dominant individuals preferentially occupy middle positions, which shelters them from predator attacks…..and that brings us to… Flocking. A. Flocking behavior exists as a balance, a trade-off, between costs and benefits, like many other animal behaviors. B. The principle cost is increased intra-specific competition. Flocking is, afterall, the antithesis of territoriality. Although there are exceptions (we’ll get to them later). C. The principle benefit is reduced predation risk. This advantage is realized via several, non-mutually exclusive, routes: 1. The flush of a large flock of birds may confuse an attacker and reduce its probability of success. Also, a tight flock may actually pose a threat to a fast-approaching falcon. 2. As long as the predators cannot congregate in proportion to the flock size (most cannot), then predators may become satiated and individuals in a flock may thus suffer less predation risk. 3. As flock size increases, the probability that a single given forager is killed decreases (as long as attack frequency does not increase in proportion to flock size). 4. Predator detection improves with increasing flock size. Many pairs of eyes scanning for a predator are more likely to spot it early than a single pair. Even without communication, the flush of the “spotter” will alert other flock members, but in may cases this group flush response is enhanced by ritualized alarm calls. 3 i. IV. alarm calls may appear advantageous to all but the sucker who gave it, but in fact they are “selfish” behaviors, for 3 reasons. ii. Kin Selection. First, alarm calls are often given in flocks of related birds. By helping its relatives survive, an individual actually helps pass some its own genetic material onto the next generation, since it shares genes with its relatives. Thus, natural selection favors helping ones kin – that is called kin selection. iii. But even in flocks of unrelated individuals, by getting the whole flock to flush simultaneously, the caller reduces its own probability of being nabbed for the reason above. iv. Third, alarm calling may actually attract other flock members. This attraction would be particularly advantageous for a dominant birds, which would then occupy the safe center of the flock. Test of the trade-off with our data. A. First, lets think about the trade-off. 1. The cost of flocking is higher intra-specific competition for food, and the benefit is reduced predation risk. 2. The effects of competition for food are strongest when food is scarce (costs of flocking go up with decreasing food). 3. Thus, flocking should be favored (benefits>costs) when food availability is high, but discouraged when food is scarce. B. Before we get into testing that, let’s look at our overall patterns. C. Foraging Efficiency. 1. First, foraging efficiency (measured as the time to find 5 macaroni) increased as food availability declined. 2. Also notice that, in general, the flocking experiments had lower foraging efficiencies than the territorial experiments this is because instead of searching for macaroni, foragers were busy chasing each other around and pulling flags. This finding illustrates the cost of flocking -enhanced competition means lower foraging efficiency. D. Starvation. 1. Second, notice that starvation increased in later days when food was less available. Fewer macaroni means more starvation (good thing we had the M&Ms). 2. More interestingly, note that starvation was higher in the experiments lacking predation than those with predation, probably because predation is a "killing agent" that is "compensatory," which simply means that the falcons killed some foragers that probably would have died anyway due to starvation. [This simple fact, that predation is compensatory, allows the hunting (a form of predation) of some species to continue without detrimental effects to their populations.] 4 V. VI. E. Predation. 1. Third, notice that predation is (overall) higher for territorial foragers than for foragers in a flock. 2. This is because a flock can more easily detect an approaching predator due to cooperative vigilance -- in our model this was simulated by a single member of the flock yelling a falcon's name to protect the entire flock (a.k.a., the "Jose Mata Effect", man that guy was vigilant!!!). This finding illustrates the benefit of flocking -- reduced predation risk. F. Survival. 1. Overall. a. Fourth, examine the probabilities of survival for the four experiments. Notice that in the absence of predation (green and yellow lines), flocking individuals fared worse (lower survival) than did territorial foragers. This makes sense, these two experiments modeled the costs (competition) but not the benefits (reduced predation) of flocks, so of course it was better not to flock. b. Notice also that survival rates in the non-predation experiments (green and yellow) were high at first, then plummeted well below the survival rates of the experiments with predation (blue and red lines). This is because predation, by removing foragers from the population early in the study, effectively kept food from becoming overly depleted late in the study. In fact, in the presence of predation, some foragers managed to still find 5 macaroni on late days because some other hapless foragers (read: Matt) kept getting picked off by the falcons (a.k.a. the "Eva Spens Effect"!!), and food remained relatively abundant. c. This finding illustrates how predation can help stabilize populations which may otherwise crash as a result of exhausted local food supplies. 2. To flock or not to flock?? a. Lastly, in the presence of predation, we ask the big question: To flock or not to flock? From our data, we can see that the flocking foragers had higher survival than territorial foragers up to about day 13 or 14, after which territorial birds fare better...the lines cross!! b. This finding fits our prediction: on day 13 or 14, macaroni became so scarce that the cost of high competition in a flock outweighed the benefit of reduced predation risk. Take home message: flock until food becomes scarce, then defend a territory!! Alternate take home message: If you find yourself, for whatever reason, searching the grass for pasta and they're lots around, find a friend so you don't get killed by falcons. Flock size (see figure 14-8 in text) Mixed species flocks...I just have hand written notes on this….it’s fairly straightforward…see text pp 343-345)