[Your name]

advertisement

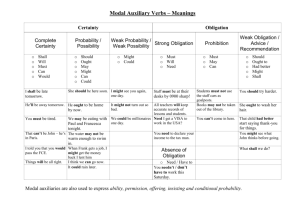

![[Your name]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007889377_2-fea5a8fe62b7007a3251842889d579f4-768x994.png)

Gabriela Kuczma Modality in legal texts: an analytic study of translation between English and Polish Praca licencjacka napisana w Instytucie Filologii Angielskiej Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza pod kierunkiem dra Grzegorza Krynickiego Poznań, 2010 OŚWIADCZENIE Ja, niżej podpisany/a student/ka Wydziału Neofilologii Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu oświadczam, że przedkładaną pracę dyplomową pt. napisałem/am samodzielnie. Oznacza to, że przy pisaniu pracy, poza niezbędnymi konsultacjami, nie korzystałem/am z pomocy innych osób, a w szczególności nie zlecałem/am opracowania rozprawy lub jej istotnych części innym osobom, ani nie odpisywałem/am tej rozprawy lub jej istotnych części od innych osób. Jednocześnie przyjmuję do wiadomości, że gdyby powyższe oświadczenie okazało się nieprawdziwe, decyzja o wydaniu mi dyplomu zostanie cofnięta. (miejscowość, data) (czytelny podpis) 2 Table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................... 3 LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................... 5 LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER 1: THEORETIC APPROACH TO MODALITY AND LEGAL TEXTS8 1.1. MODALITY: CONCEPT, DEFINITION AND TYPES. ....................................................... 8 1.2. MODALITY AS A LANGUAGE UNIVERSAL ............................................................... 12 1.3. LEGAL LANGUAGE AND LEGAL TEXTS ................................................................... 13 1.4. ASPECTS OF LEGAL TRANSLATION......................................................................... 15 CHAPTER 2: MODALITY IN ENGLISH AND POLISH ....................................... 18 2.1. MODALITY AND ITS FORMS OF EXPRESSION .......................................................... 18 2.2. FORMAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ENGLISH MODAL AUXILIARIES ...................... 19 2.3. FORMAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE POLISH MODAL AUXILIARIES ......................... 21 2.4. ANALYSIS OF SELECTED MODAL AUXILIARIES IN ENGLISH AND POLISH ................ 23 2.4.1. Analysis of selected modal auxiliaries in English ........................................ 23 2.4.2. Analysis of selected modal auxiliaries in Polish .......................................... 27 2.5. MODAL REVOLUTION – THE CASE OF SHALL .......................................................... 30 CHAPTER 3: MODALITY IN LEGAL TEXT TRANSLATION – CASE STUDY32 3.1. RESEARCH QUESTIONS .......................................................................................... 32 3.2. METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................... 32 3.3. RESULTS OF THE ANALYSIS ................................................................................... 34 3 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................. 41 REFERENCES.............................................................................................................. 42 4 List of tables Table 1: English and Polish modal words, their occurrences and translations ............... 37 Table 2: English and Polish modal words, their occurrences and translations ............... 37 5 List of figures Figure 1: Frequency of modal forms in English legal texts ............................................ 35 Figure 2: Frequency of modal forms in Polish legal texts .............................................. 36 Figure 3: Box and whisker plot for weighted pol and eng variables .............................. 38 Figure 4: Shall and its forms of translation into Polish .................................................. 40 6 Introduction Legal language has always been considered as very complex and difficult to comprehend. Problems with understanding legal texts have not only the laymen but also lawyers. For this reason, legal texts constitute a significant challenge also for translators who have to interpret them as well as find the perfect translation which will not violate their original meaning and more importantly will not lead to legal consequences. The phenomenon of modality serves as a focal point of legal texts because it describes necessity, permissibility, probability, and their negations. The present paper examines conception of modality used in Polish and English legal texts. It is divided in three chapters. The analytical part of the paper is preceded by two theoretical chapters which introduce the theoretical background for the subject in focus. The initial chapter provides definition of modality and its classification as well as characteristics of legal language and aspects of legal translation. The next chapter moves on to the forms of expression of modality and presents formal characteristics of Polish and English modal auxiliaries. In addition, there is also analysis of selected modal auxiliaries in Polish and English. The third and last chapter constitutes the core of this paper. It contains a case study of Polish and English legal texts based on the translation memory of LexTranslaide. The research is to explore the frequency of modality in Polish and English legal texts as well as its distribution and translations. Outcomes of the research are to make modality more comprehensible and easier to translate. 7 Chapter 1: Theoretic approach to modality and legal texts 1.1. Modality: concept, definition and types. Modality belongs to the linguistic category which poses great problems in creating one clear-cut definition that would explicitly describe it. These problems stem from the fact that the criteria on the basis of which modality is construed are not precise. This, in turn, is the result of different perspectives people have on the reality. As Koseska-Toszewa rightly noticed (1995: 153) there is one common feature that combines all the definitions of modality. All linguists seem to define modality as attitude the utterer/writer has toward what he or she is saying/writing. This attitude can involve giving a statement without reservation about the situation that is being described, as well as imposing certain limitations on the truthfulness of the statement. Thus, modality expresses how much the statement producer is convinced about the truthfulness of the statement he or she is producing or how much he or she finds it untrue. In other words, “modality of a grammatical form is the quality or state in question. These include the assertion or denial of any degree or manner of affect, belief, certainty, desire, obligation, possibility, or probability on the part of the utterer”(State Master Encyclopedia – Linguistic Modality 2010). Tim Rowland, after Michael Stubbs, claimed that there is “no utterance that is neutral with regard to the belief and commitment of the speaker, and urged the importance of the study of indicators or ‘markers’ of propositional attitude […]” (Rowland: 3) whenever speakers (or writers) say anything, they encode their point of view towards it: whether they think it a reasonable thing to say, or might be found to be obvious, questionable, tentative, provisional, controversial, contradictory, irrelevant, impolite, or whatever. [...] All sentences encode such a point of view [...] and the description of the markers of such points of view and their meanings should therefore be a central topic for linguistics. (Stubbs 1986: 1) 8 One can clearly notice that modality as a concept is related to the way languages signify speaker’s interpretation of the state of affairs in a given discourse. In other terms, modality can be understood as a signal of the speaker’s involvement in what they say. This involvement “takes various forms realized linguistically in various categories of meanings or semantic roles known as modal categories. These categories have been approached from different perspectives: philosophical, semantic and linguistic” (Mukhani 2008:7). Nevertheless, there is no substantial correlation between these approaches. It results from essentially different research aims and workings at different level of abstraction. According to Kiefer (1994:2514) modality has a different, philosophical perspective. He relates modality to “the relativization of the validity of sentence meanings to a set of possible worlds. Talk about possible worlds can thus be construed as talk about the ways in which people could conceive the world to be different”. This concept of modality gives reason to perceive modality as a universal linguistic phenomenon, even though it is realized in different means. Comprehending Kiefer’s philosophical point of view is easier when distinguishing between two aspects of this category (http://www.statemaster.com/encyclopedia/Linguistic-modality): the dictum: what is said the modus: how it is said (that is, the speaker’s cognitive, emotive, and/or volitive attitude about what is said). For example dictum ‘It is cold outside’ can have following modi: I think it is cold outside I believe it is cold outside. I know it is cold outside. I hope it is cold outside. I doubt it is cold outside. It must be cold outside. It might be cold outside. It could be cold outside. It needn’t be cold outside. It is probably cold outside. Perhaps it is cold outside. 9 It is possible that it is cold outside. It is certain that it is cold outside. It is likely that it is cold outside. As demonstrated in the examples above, there are a number of possible expressions regarding one and the same fact. One of the most clear-cut interpretations of this notion was proposed by the semanticist Angelika Krazer. Krazer’s (1981) analysis of the set of possible worlds and ordering of those worlds implies that the world speaker/writer refers to depends on his or her subjective perception of the reality. This, in turn, leads us to assumption that there can be as many interpretations of reality as there are people. Therefore, linguists have to tackle the great number of different perceptions of the reality to subcategorize modality as linguistic notion. One of the most popular divisions distinguishes the following three types of modality: Alethic modality (Greek: aletheia, meaning ‘truth’) – in simple terms it refers to the truthfulness of a statement. To be more specific, alethic modality deals with necessary, or possible truthfulness of statements on the one hand and impossible or accidental on the other. The necessity or possibility of the truthfulness or falseness of a statement springs from the objective external factors and is based on logic, laws of nature and some scientific assertions. When it comes to logical structure in alethic modality, it consists of two judgments between which occurs an implication – truthfulness of one judgment remains in necessary relation with the truthfulness of the other judgment. The below example presents this relation: (1) Musisz płacić podatki, żeby uniknąć kary. = Niemożliwe, że zostaniesz ukarany, jeżeli będziesz płacić podatki. = Jest koniecznie prawdziwe, że unikniesz kary, jeśli tylko będziesz płacił podatki. ‘You must pay taxes in order to avoid punishment. = It is impossible that you will get punished if you pay taxes. = It is true that you will get punished if you do not pay taxes.’ Alethic modality expresses relation of the sentence content to the reality independently of the sentence utterer’s/writer’s point of view and therefore, it is often called objective modality. 10 Epistemic modality (Greek: episteme, meaning ‘knowledge’) – “deals with a speaker's evaluation/judgment of, degree of confidence in, or belief of the knowledge upon which a proposition is based. In other words, epistemic modality refers to the way speakers communicate their doubts, certainties, and guesses. More technically, epistemic modality may be defined as (the linguistic expression of) an evaluation of the chances that a certain hypothetical state of affairs under consideration (or some aspect of it) will occur, is occurring, or has occurred in a possible world which serves as the universe of interpretation for the evaluation process” (Nyuts 2001: 21-22). In other words, epistemic modality reflects our own convictions about truthfulness or falseness of an assertion while we are making it. Example of a sentence with epistemic modality: (2) Jej samochodu nie ma w garażu. Musiała już pojechać do pracy. = Nadawca jest pewny, że ona pojechała już do pracy. ‘Her car is not in the garage; she must have already gone to work. = The speaker is sure she has left for work.’ Deontic modality (Greek: deon, meaning ‘duty’) – it signifies how the world should be “according to certain norms, expectations, speaker’s desire, etc. In other words, deontic expressions indicate that the state of the world (where 'world' is loosely defined here in terms of the surrounding circumstances) does not meet some standard or ideal, whether that standard is social (such as laws), personal (desires), etc. The sentence containing the deontic modal generally indicates some action that would change the world so that it becomes closer to the standard or ideal” (Loos 2009). To put it in simpler terms, deontic modality refers to necessity or possibility of executing action as a result of the modalizing subject’s attitude. Example of a sentence with deontic modality: (3) Oni mogą zjeść teraz ciasteczka. ‘They may eat the cookies now.’ The modalizing subject (the person who says/writes the statement) allows the modlized subject (they/oni) to eat cookies (when the possibility is a result of the modalizing subject’s attitude) or informs about the possibility of eating the cookies (when the possibility is not a result of the modalizing subject’s attitude). 11 Deontic modality falls into three subcategories (Bhat 1999): Commisive modality – it deals with speaker’s commitment to do something, like a promise or threat; e.g. I shall call her. Directive modality – it refers to commands, requests, etc.; e.g. Stop!, You’ve got to buy this jacket! Volitive modality – it denotes wishes, desires, etc.; e.g. If only I were slim! All types of modality are realized in various ways in different languages. They are expressed either grammatically or non-grammatically (usually lexically). Grammatical realization of modality happens by the means of modal verbs (e.g. in English: can, must; in Polish: móc, musieć) or specific grammatical verb moods (indicative, imperative or subjunctive). Non-grammatical modality is realized through the use of adverbials (e.g. in English: perhaps, probably) or through a precise intonation (not in written texts though). The way modality is expressed determines subtle or not-so-subtle differences in translation. Some forms of expression may place emphasis on certain features of modal meaning. Thus, linguists traditionally classify modality into sentence modality and verbal modality. Sentence modality deals with types of sentences, such as declarative (a statement), imperative (a command), interrogative (a question), optative (a wish), exclamatory (an exclamation), etc. Verbal modality, on the other hand, deals with the modal verbs and the mood projected on them. 1.2. Modality as a language universal Language universals are features that all languages (absolute universals) or vast majority of languages (tendencies) have in common. It other words, a language universal can be treated as a statement that is true to all or most languages. Linguistics owes a lot to Joseph Greenberg (1966) in this matter. He aimed at showing how human brain processes language. Language universals are one of the means by which linguists can achieve that. It is easy to notice that any utterance in any language consists of a stream of sounds, which are chosen out of a set determined by the way speech organs are built. Those sounds can be classified as a rather small finite collection of phonemes. Phonemes, in turn, create syllables in all 12 languages. Another universal notion is morpheme, i.e. the smallest meaningful unit which possesses one phonetic form or a small number of forms depending on the context. Modality also demonstrates features of a language universal. The fact that English and Polish are translatable supports the idea of modality as a language universal. Nevertheless, modality in each language in question has a different realization. This should lead to tracing an adequate variable for instances of modality loss and mismatch between texts in a source language and its translations into the target language. Even though similar notions and concepts are expressed in different languages, translation of modality between English and Polish (particularly in legal texts) requires exceptional attention. This argument is supported by Lyons’(1977: 791) statement: “The ambiguity found in sentences containing ‘must’ and ‘may’ is also found in comparable sentences, in other languages. This suggests the existence of modality, together with its accompanying difficulties, in most languages”. In other words, modality is widespread in language in general and in legal discourse and despite different realizations of modality in English and Polish it must be by some means realized. 1.3. Legal language and legal texts Legal texts can be classified in many ways depending on their functional nature. Legal English consists of several classes of writings which depend on their communicative function. As Hiltunen states (1990: 81), there are three different types of legal writing to be distinguished: academic texts which consist of academic research journals and legal textbooks, juridical texts covering court judgments or law reports, legislative or statutory writings consisting of Acts of Parliament, contracts, treaties, etc. Legal texts are written in legal language which possesses a number of specific fea- tures. First of all, it’s a language which cannot be qualified as languages like Polish, English, Spanish or German are. It is based on ordinary language but it has its own usage domain and certain linguistic norms (they are usually associated with particular phraseology, glossary and hierarchy of terms and meanings). What is more, legal language is used for special purposes. Therefore, it has a very specialized vocabulary depending on the branch 13 of law it describes. Legal language is also used by a very narrow group of professionals in formal settings. Hence, it might not be comprehensible by the general public. Legal language has strict rules when it comes to role taking and participation in its realization. It is by some means connected with the Speech Act Theory (Austin: 1962). According to this theory, speaking is not just semantics. The words we utter are affected by the situation we are in while speaking and by our listener. This is why sentencing someone to death, for example, will not have such interpretation unless it is announced in a court room by a judge or other authority empowered to pass this sentence. It is important to look at the style in which legal texts are documented. This style can be defined as direct and having only one interpretation. Intelligibility and clarity of legal texts such as treaties, statues, agreements, etc. is highly desirable because their role is to protect rights of people as well as impose obligations on them. Hence, authors of legal texts should very precisely word them so that they are of high degree of clarity and adequacy. Another essential aspect of legal texts is that they regulate behavior of individuals in mutual relations and in relation with the whole society and with the legislator itself. The rule of law is always a logical proposition despite the fact that it might not be stated in a form of a legislative document. For that reason, it must leave the receiver with no doubts and be built on reliable and up-to-date information. According to Šarcevic (1997: 167) law tends “towards more direct expression, frequent repetition and more detail, in order to limit judicial discretion”. Legal texts are also known for their culture-sensitive and culture-specific character. It stems from the fact that legal system in each country is different. What is more, the differences are observed not only between countries but also within a country. Communities of a certain country usually lead a very specific lifestyle which is not similar to the one of their neighbors and as a result they need national legislations tailored to their social, political, financial, religious and all other life activities. Hence, their legal traditions and regulations are encoded in their nation-specific legal language (e.g. in the Polish legal language one can observe a very often use of the predicate winien which is not commonly used by the ordinary citizens). The mentioned Speech Act Theory refers to another feature of legal language. It substantially depends on the role of a person involved in a legal performance. It means that legal language of, for example, lawyers will differ from the one used by judges or contrac- 14 tors. This derives from the fact that each group of professionals has different responsibilities, liabilities or rights. Legal texts would not do without modality. The directive and expository nature of those texts requires particular ways of encoding modal meanings such as prohibition, advice, obligation, recommendation, advice, authorization, etc. Linguistically speaking, there are various methods of encoding modal meanings and they depend on the linguistic system of the language as well as on the legal system in which they operate. 1.4. Aspects of legal translation The “(...) not every man is able to give a name, but only a maker of names; and this is the legislator, who of all skilled artisans in the world is the rarest (...) But (...) the knowledge of things is not to be derived from names. No; they must be studied and investigated in themselves (...) and no man of sense will like to put himself or the education of his mind in the power of names; neither will he so far trust names or the givers of names as to be confident in any knowledge which condemns himself and other existences to an unhealthy state of unreality (...)” Plato, Cratylus The characteristics mentioned in the previous section give evidence to the high level of difficulty and specificity of translation modality in legal texts. According to Harvey (2002: 177) legal translation is “the ultimate linguistic challenge combining the inventiveness of literary translation with the terminological precision of technical translation”. It derives from differences between the common law and civil law systems as well as the systembound nature of legal terminology. Following Plato’s wisdoms we cannot rely on words as guides to the perfect state because we are not sure if the lawgiver did a good job in creating those words. Legal translators are somewhat ‘the lawgivers’. It depends on them and their skills how the law will be interpreted. Seemingly, legal translators should be conversant with law, but some of the linguists (Alcaraz & Hughes 2002) claim it is not necessary. What is essential in order to make a good legal translator is high competency in legal conventions of both source and target language texts (Šarcevic 1997). Therefore, even if “lawyers cannot expect translators to produce parallel texts that are identical in meaning, they do expect them to produce par15 allel texts that are identical in their legal effect” (Altay 2002: 1). Additionally, receivers of a translated text should understand it in the same way as the source-language audience does. This notion was defined as ‘dynamic equivalence’ by Nida and Taber (1964). This is why translators should bear in mind the purpose of the text they translate as well as its receptors. The translated text can be used as evidence in court and if not adequately translated, it can bring disastrous consequences. In order to avoid such situations one can follow Nida’s (1964:164) four principals of a good translation. These are: making sense, conveying the spirit and manner of the original, having a natural and easy way of expression, producing a similar response. Those requirements are not always easily met. As mentioned earlier, legal systems of source and target language differ because they reflect their culture and institutional traditions, making translation between the two languages even more difficult. For this reason, translation studies put emphasis on cultural awareness as well as differences in legal systems. This is very accurate for translation between English and Polish as both legal systems and cultures vary in countries where those languages are spoken. Linguistic barriers pose another problem translators have to tackle. It often happens that commonly used in source language grammatical or lexical structures will not correspond to the ones of the target language. Translator’s task is to find an equivalent structure in the target language. It is crucial to make sure that the structure has the same function as it does in the source language. According to Nida, translators should not worry too much about the style of the target text when finding an equivalent because “correspondence in meaning must have priority over correspondence in style” (Nida 1964: 173). Terminological incongruity can take several forms “ranging from identical concepts (very rare) or near equivalence to conceptual voids without any equivalents in the TL” (Altay 2002). American theorist Lawrence Venuti (1995) came up with two techniques for approaching incongruous concepts of translation (including legal translation): domesticating and foreignizing. Venuti defines foreignizing method as “an ethnodeviant pressure on those values to register the linguistic and cultural difference of the foreign text, sending the reader abroad” (Venuti 1995: 20). Domesticating method, on the other hand, is described as the opposite: “an ethnocentric reduction of the foreign text to target-language culture values, bringing the author back home” (Venuti 1995: 20). This basically means that foreignization, unlike domestication, promotes cultural and linguistic transfer deliberately leaving a gap between original and target conventions. Domestication aims at minimizing strangeness of the target text. In summary, legal translators stand in front of a very difficult task of bridging various legal systems, languages and cultures. Keeping in mind the subject of this paper – mo16 dality, English into Polish translators are not only obliged to find the specific modal meaning, but also they have to make a decision of how this meaning will be used in Polish. Speech Act Theory plays a significant role here because it helps to identify modal meanings uttered or written by the original producer. It also helps with measuring adequacy of translation and assessing functions of the target modal meaning. Taking into account all the problems and difficulties while translating legal texts, it is suggested to aim at “providing literate rather than literal translation” (Kahaner 2005: 2). 17 Chapter 2: Modality in English and Polish 2.1. Modality and its forms of expression Modality is a very complex notion as it not only has various definitions and subtypes but also numerous forms of expression. One can distinguish the following variety of expressions with modal meanings found both in English and Polish (there are more elements which belong to each category than those provided below): Modal auxiliaries: (4) ENG: The company should/must/might/may/can/could/will/would/shall submit the documents by the end of the month. (5) PL: Firma powinna/musi/może/ma złożyć dokumenty do końca miesiąca. Semimodal verbs: (6) ENG: The company has to/ought to/needs to submit the documents by the end of the month. (7) PL: Należy/wolno/trzeba złożyć dokumenty do końca miesiąca. Nouns: (8) ENG1: There is a possibility that the company submitted the documents by the end of the month. (9) ENG2: There is an obligation to submit the documents by the end of the month. (10) PL: Firma ma możliwość/obowiązek złożenia dokumentów do końca miesiąca. Adverbs: (11) ENG: Perhaps/Allegedly/Probably/Definitely/Obviously/Likely/Maybe, the compa- ny submitted the documents by the end of the month. 18 (12) PL: Prawdopodobnie/Być może/Rzekomo/Z pewnością/Oczywiście(że) firma złożyła papiery przed końcem miesiąca. Adjectives: (13) ENG: It is possible/obligatory/necessary/required to submit the documents by the end of the month. (14) PL: Złożenie dokumentów przez firmę jest możliwe/obowiązkowe/konieczne do końca miesiąca. Conditionals (15) ENG: If the company wants to submit the documents, it has to do it by the end of the month. (16) PL: Jeśli firma chce złożyć dokumenty musi to zrobić do końca miesiąca. Traditionally, linguists use modal auxiliaries or semimodal verbs in order to present illustrative examples. This stems from the fact that these grammatical categories have very interesting properties, and thus may pose the greatest problem in legal translation. The author will concentrate on these elements to present modal meanings in the English and the Polish languages. English and Polish are two typologically different languages. English is a Germanic language (West Germanic to be specific) whereas Polish is a Slavic language (West Slavic to be specific). Different language families should make translators aware of the possible distinct characteristics of modal elements and their broader or narrower modal meanings in each language in question. 2.2. Formal characteristics of the English modal auxiliaries English modal auxiliaries can by characterized by the following features (Kakietek 1976: 1): They have only finite forms: (17) I can send the money. (18) *I am canning send the money. They undergo Subject-Auxiliary Inversion: (19) I should send the money => Should I send the money? 19 They undergo Negative Placement: (20) They do not undergo Number Agreement: (21) I should not send the money. I/you/he/she/it/we/they should send the money. They invariably take the initial position in the VP: (22) I should send the money. (23) *I send should the money. They do not combine internally: (24) *I should can send the money. Nevertheless, there are some cases in which combinations of two modals within the same VP are allowable, e.g. in Scots. This notion solely depends on the incompatibility of the modal meanings. The below examples attest that conceptions such as willingness, necessity or possibility do not have to be mutually exclusive. (25) The representative may have to pay another fine. – In this sentence ‘may’ indicates possibility and ‘have to’ necessity. (26) The representative may let his proxy sign the documents. – In this sentence ‘may’ indicate possibility and ‘let’ permission. (27) The representatives of this company must be able to speak three foreign languages. – In this sentence ‘must’ indicate necessity and ‘be able to’ ability. They lack the category of Imperative: (28) Open the window, please! (29) *Must open the window, please! They take the bare infinitive: (30) I should send the money. (31) *I should to send the money. (32) *I should sending the money. They are intransitive verbs and have no past participle forms. Therefore, English modal auxiliaries cannot be passivized. (33) *The money is should save. Modal verbs can be seen in the passive voice structures but not in the role of a passivized verb. In order to build a passive voice sentence with a modal one should follow this formula: modal verb + be (in the correct form) + past participle of the main verb. 20 (34) The money should be saved. 2.3. Formal characteristics of the Polish modal auxiliaries Taking into account English formal characteristics of modal auxiliaries, none of the Polish modals can be qualified as a modal auxiliary. The main Polish verbs regarded as modal auxiliaries: móc, musieć, mieć and powinien share similarities with the English modals only in some aspects, e.g. they take the bare infinitive and they do not co-occur. When it comes to the remaining aspects they differ in Polish. Hence these characteristics (Kakietek 1976: 2): They are inflected for person, number and tense: (35) Muszę podpisać dokumenty. (1st person, singular number, present tense) (36) Musieliście podpisać dokumenty. (2nd person, plural number, past tense) They possess non-finite forms: (37) Obywatel mając na uwadze dobro rodziny może zgłosić się po zasiłek. – where mając is a present participle form of mieć. They may occur non-initialy in the VP: (38) Każdy obywatel będzie musiał dokonać wpłaty. In the above sentence the active past participle musiał follows tense auxiliary będzie. Verb być in the future tense form seems to be the only verbal element that can precede a modal auxiliary. They do not have to precede the subject NP in questions: (39) Czy premier musi dokonać wpłaty? – here the subject premier precedes the modal musi. (40) Czy musi premier dokonać wpłaty? – here the subject follows the modal They undergo negation. Unlike in English, negation particle nie invariably precedes the modal: (41) Premier nie musi dokonać wpłaty. (42) *Premier musi nie dokonać wpłaty. 21 Polish modals take the main verb in the bare infinitive form. Other elements in the sentence structure with a modal auxiliary are described by the main verb and not by the modal auxiliary. (43) Mogę dokonać wpłaty. (44) *Mogę dokonuję wpłaty. They do not co-occur; combinations of two modals within one VP is not possible: (45) *Musi móc dokonać wpłaty. – Such constructions may be grammatically correct only in specialized and not ordinary contexts, e.g.: (46) Może pozwolić swojemu przedstawicielowi podpisać dokumenty. – where może signals possibility and pozwolić indicates permission. They lack the Imperative category: (47) Otwórz okno, proszę! (48) *Musisz otwórz okno, proszę! They cannot be passivized as they do not have past participle forms: (49) Mogę dokonać wpłaty. (50) *Wpłata jest móc dokonana. Passive voice can be created with a Polish modal auxiliary only when it is not the main verb in the sentence. One should follow this formula: modal verb (in the correct form) + być + past participle of the main verb. (51) Wpłata może być dokonana. As have been demonstrated, despite the seeming similarities in some aspects, Eng- lish modal auxiliaries present a significantly wider range of variety than the Polish ones. For this reason, Polish is often forced to resort to the use of a completely different sentence construction. For example: (52) Ona dostanie tę pracę jutro. ‘She shall get the job tomorrow’. Polish translation does not contain any special word by which the particular meaning distinction could be rendered. The verb is in the perfective future tense form and the whole sentence seems to lack a special kind of intonation which the English equivalent involves. Another example that illustrates differences in modal constructions between English and Polish refers to a past habitual action. In English it can be expressed by the means of e.g. ‘would', as in: (53) I would sometimes argue with my boss. 22 Polish takes over the function of this modal by the means of ‘imperfective’ past tense form of the main verb (it often appears with an adverb of frequency): (54) Czasami kłóciłam się z moim szefem. As shown in this section, English and Polish modal auxiliaries differ in their construction to such extent that legal translators should not ignore the differences and keep them in mind while translating, as the meaning may be distorted and lead to legal consequences. 2.4. Analysis of selected modal auxiliaries in English and Polish 2.4.1. Analysis of selected modal auxiliaries in English This section provides a detailed description of selected modal auxiliaries in English, i.e. must, can and should. 2.4.1.1. Must ‘Must’ is semantically the strongest out of all modal auxiliaries. It is used to show: Probability or to make a logical assumption, as in: (55) The accused must be out of town. His neighbors haven’t seen him for a while. This is an example of the use of ‘must’ in epistemic modality. Here ‘must’ is used by the speaker/writer to make a firm judgment on the basis of some evidence (the fact that the neighbors haven’t seen the accused for a while). ‘Must’ offers a reasonable conclusion (Palmer 2001: 25). Necessity or obligation, as in: (56) All citizens must pay taxes. It is worth drawing attention to the specificity of this sentence and comparing it to the following sentence: (57) All citizens have to pay taxes. 23 Polish legal translators use the same Polish modal auxiliary musieć in translation of the both sentences. Nevertheless, the two English sentences indicate a different source of the obligation. ‘Must’ denotes obligation directly expressed by the speaker/writer, whereas ‘have to’ refers to the external obligation expressed e.g. by some other person, law acts, agreements. In other words, when a speaker/writer uses ‘must’ the obligation comes from him or her – he or she says that there is an obligation. ‘Have to’ is used when the speaker/writer talks about the obligation given by some other people or authorities and only repeated by the speaker/writer. Prohibition (negative form), as in: (58) All citizens must not evade paying taxes. The negative form ‘mustn’t’ does not mean lack of obligation as a Polish interpreter could think due to the Polish negative form of musieć – nie musieć, though it renders prohibition. ‘Must not’ negates the proposition (All citizens must evade paying taxes), but it is ‘needn’t’ that negates the modality: (59) All citizens needn’t evade paying taxes. A very important feature of the modal ‘must’ is the fact that it has no past tense form. This is why the following sentence is grammatically incorrect: (60) *All citizens must pay taxes yesterday. This does not mean that there is no way to express ‘must’ and its modal meanings in the past tense. The most common construction to do so is the one with the past form of ‘have to’, namely ‘had to’. (61) All citizens had to pay taxes yesterday. The above example presents a past form of ‘must’ which expresses obligation. If one wants to indicate a conclusive meaning of ‘must’, he or she should use ‘must + have + past participle’, as in: (62) The criminal must have been seen by someone. 24 2.4.1.2. Can Modal auxiliary ‘can’ is also semantically strong, however, less than ‘must’. It has the following meanings: Suggestion of a possibility or giving an option, as in: (63) Senior citizens can apply online. Example (63) implies that senior citizens are allowed to apply online, so they have the possibility to apply online but they do not the obligation to do so. This is the deontic meaning of ‘can’. Ability, as in: (64) The representative can speak three foreign languages. Example (64) implies that the representative have the internal disposal of speaking three foreign languages. In this meaning ‘can’ may be sometimes substituted by ‘be able to’. Asking for or giving permission, as in: (65) The students can leave now, the class is over. Example (65) presents alethic meaning of ‘can’ and suggests that the students have the permission to leave because of the objective circumstances (the class is over) indicate that. There is one more auxiliary verb, namely ‘may’ that presents the same modal meaning and is therefore very often used as a synonym of ‘can’. Showing impossibility, as in: (66) Senior citizens cannot apply online. Example (66) presents the negative form of the modal auxiliary ‘can’ and it conveys impossibility. It is worth mentioning that while ‘mustn’t’ does not negate the modality, ‘cannot’ does negate it. If one does not want to negate modality but only proposition, he or she should use ‘may not’. Modal auxiliary ‘can’ has its past tense form which is ‘could’. It is usually used to show past ability, as in: The representative could speak three foreign languages when he was young. ‘Could’ is also used to: ask polite questions: 25 (67) Could you sign this document, please? show possibility (and impossibility): (68) The authorities could (not) be in the position to answer the question. – They had (did not have) the essential information to do so. However, these meanings of ‘could’ in the author’s opinion are not very likely to appear in legal texts. The last use of ‘could’, namely suggesting a probability or opportunity or giving an option is expected to be present in legal texts. Example (69) presents this use of ‘could’: (69) The president could try consulting the minister of defense in the case of a coup d'é- tat. 2.4.1.3. Should ‘Should’ has also a weaker modal meaning than ‘must’ and it does not express necessity, as many people probably think. “It expresses rather extreme likelihood, or a reasonable assumption or conclusion” (Palmer 1979: 59) It is used to show: advisability, as in (70) obligation: (71) The poor should apply for the financial aid. The poor should submit the application for financial aid by the end of the month. expectation: (72) The poor should receive the financial aid within 30 days. There are two important aspects of the modal auxiliary ‘should’. First of all, it is formally used as the past tense of ‘shall’ but only in the reported speech. Secondly, ‘should’ can be sometimes used interchangeably with the semimodal ‘ought to’, as in: (73) You should pay for it tomorrow. (74) You ought to pay for it tomorrow. In this context both forms ‘should’ and ‘ought to’ semantically relate to ‘must’ be- cause they mark epistemic necessity. However, ‘must’ seems to lay an absolute obligation, not envisaging non-compliance. ‘Should’ and ‘ought to’ express less absolute obligation 26 and do not exclude non-compliance” (Palmer 1988: 132). It is also worth mentioning that ‘should’ is more common in informal settings and therefore ‘ought to’ is more likely to appear in legal texts. These aspects should be taken into account when translating and analyzing legal texts. When it comes to the negative form of ‘should’ – ‘shouldn’t’, it does not negate the modality of ‘should’ but only the proposition. In order to negate the modality of ‘should’ one could use ‘needn’t’ or ‘needn’t have + past participle’ (in the past tense). Compare: (75) The poor shouldn’t apply for the financial aid. (There is a tentative obligation not to act) (76) The poor needn’t apply for the financial aid. (There is absence of obligation in gen- eral) Past tense is indicated by the following formula: should + have + past participle, as in: (77) The poor should have applied for the financial aid. This example implies that the poor failed to realize a necessary action. 2.4.2. Analysis of selected modal auxiliaries in Polish 2.4.2.1. Musieć Similarly to the English equivalent ‘must’, musieć is also semantically the strongest out of all Polish modal auxiliaries. It is used to express: obligation and/or relative but not absolute necessity, as in: (78) Aresztowany musi podążyć za policjantem na posterunek. The above sentence carries twofold meaning. Firstly, it denotes that the individual under arrest must follow the police officer because the law regulations say that. Secondly, the sentence implies that if the person does not follow the police officer he will be punished. Command or demand, as in: (79) Żołnierze muszą pomóc ofiarom wojny. 27 The modalizing subject (person who gives the command) does not give other option to the modalized subject (person who gets the command) but to execute the command. In other terms the modalized subject must not fail to perform the command. Demand is usually expressed by placing the modal auxiliary in the initial position, as in: (80) Musicie pomóc ofiarom wojny. This form is very direct and personal therefore, the recipient is more likely to exe- cute the demand. Wish, as in: (81) Musimy wygrać tę wojnę. The above example presents what the speaker/writer wishes to happen and what he or she does not approve of – not winning the war. English modal auxiliary ‘must’ does not express such meaning. Probability, as in: (82) Podejrzany musi się ukrywać, ponieważ nikt go dawno nie widział. Polish musieć is not often used to express probability. More popular form of expressing this modal meaning is realized by the means of adverbs: pewnie or z pewnością. Musieć can be expressed in the past but unlike the English ‘must’ does not pose serious semantic problems and therefore will not be discussed in details. What could confuse the translator is the negation. One can place the negative particle nie either before musieć or after it but only the one before the modal auxiliary negates it. Thus, this notion has semantic consequences (Kątny 1980: 94): (83) Nie musisz…+ infinitive = nie jest konieczne, abyś…+verb (84) Musisz nie...+inf = jest koniecznym, abyś nie…+verb The sentence with musisz nie could be misinterpreted by some interpreters especial- ly by the English ones as in English negative ‘not’ is placed invariably after the modal auxiliary. In fact, musisz nie still conveys obligation, but to stop doing certain activity. Fortunately, this type of sentences is not very common and may even sound unacceptable to some native speakers of Polish. 28 2.4.2.2. Móc Móc is the Polish equivalent of the English ‘can’. It is also used to express: Suggestion of a possibility or giving an option, as in: (85) Seniorzy mogą złożyć podanie drogą elektroniczną. The above sentence indicates that the senior citizens have the option of applying online but not doing so does not lead to any (legal) consequences. This use of móc is expected to appear in legal texts. Ability, as in: (86) Przedstawiciel firmy może mówić w trzech językach. This application of móc is, however, not commonly used by the Poles. The Polish language expresses ability by other verbs: potrafić, umieć. Asking for or giving permission, as in: (87) Studenci mogą już iść, lekcja się skończyła. As has been demonstrated in the above sentence, móc reflects the lack of obligation of staying and gives permission to leave. This use of móc is exactly the same as the one of the English ‘can’. Impossibility, as in: (88) Seniorzy nie mogą złożyć podania drogą elektroniczną. In this example the modal auxiliary móc is negated. It conveys that the senior citi- zens are not allowed to vote online. This modal meaning is very similar to prohibiting ‘mustn’t’ and such translation may be expected. Móc and its past tense form should not pose translating problems, therefore a detailed description will not be provided. When it comes to negation, the problematic part of is very similar to the one of ‘must’. Compare: (89) Nie możesz…+infinitive = nie jest możliwe byś….+verb (90) Możesz nie…+infinitive= jest możliwe byś nie...+verb The first sentence negates the possibility or does not give permission to do some- thing and is equivalent to English ‘you may not’ or ‘it is not possible’. Whereas the second sentence conveys a possible activity or gives the modalized subject permission for not doing something. It can be substituted by ‘do not have to’ (hence, it also relates to ‘must’). 29 2.4.2.3. Powinien Powinien is the Polish equivalent of English ‘should’. This verb is specific when it comes to its form – it has no actual infinitive form with the final ć or c and indicates masculine 3rd person singular. It is used to express: Advisability: (91) obligation: (92) Ubodzy powinni ubiegać się o zapomogę. Ubodzy powinni złożyć podanie o zapomogę do końca miesiąca. expectation: (93) Ubodzy powinni otrzymać zapomogę w przeciągu 30 dni. There are few important aspects of powinien. First of all, it has a short form winien which seems to be more popular in legal texts than the regular form. There are also semimodal words like trzeba or należy that can be used instead of powinien, and therefore, are expected to appear in translated from English into Polish legal texts. It is also worth mentioning that powinien has no future form. (94) *Ubodzy bedą powinni złożyć podanie o zapomogę. Past form can be formed by following this formula: powinien + past form of być in, as in: (95) Ubodzy powinni byli złożyć podanie o zapomogę. 2.5. Modal revolution – the case of shall It can be agreed that legal language is very characteristic and difficult to comprehend. What is more, legal language is considered to be one of the most conservative discourses and as Christopher Williams (Williams 2009: 199) claims “the abstruseness of legal language is the result of an exclusionary policy”, meaning it is used only in specific circumstances (e.g. in a court or legal texts). Because of the special character of the legal language, there have been many calls for making it more comprehensible for the laymen. Ordinary people should not be forced to rely on lawyers’ skills to have legal texts interpreted for them. The role of legal texts translators is, therefore, even more significant as they not only translate the texts but also have to interpret them. All this have contributed to so called ‘modal revo- 30 lution’ which involves choosing finite verbal constructions in legal texts and was one of the reasons of the 1960s Plain Language Movement (consumer movement that calls for respect and rights of the ordinary citizens). The movement supporters took various aspects of legal language under scrutiny. They were propagating shorter sentences, reducing passive forms and Latinisms as well as replacing archaic words with the more contemporary ones. The most troublesome modal verb used in legal texts was ‘shall’. Linguists considered it as “ubiquitous, imprecise and royal sounding” (Mowat: 1994) and as “a ‘dead’ word never heard in everyday conversation” (Lauchman 2002: 47). They all wanted to abolish ‘shall’ from prescriptive legal texts and postulated that “shall must go” (Asprey: 1992). And it indeed happened. Around 1990s ‘shall’ disappeared from many legal texts, especially those which came from the southern hemisphere English speaking countries like Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Williams (et al. 2009:199) gives an example of South Africa’s Interim Constitution from 1994 in which one can find 1288 cases of shall, 0 cases of must, and 265 cases of may. The same text about three years later contains 0 cases of shall, 414 cases of must, and 274 cases of may. Such modal auxiliary distribution shift is for Williams an evidence for ‘modal revolution’. This notion is also observable in the Northern hemisphere English speaking countries, however, to a less extent. Those countries tend to maintain traditional legal glossary. Williams (et al. 2009: 201) conducted a research in which he compared shall-free corpus with the one that contained shall – “World data”. The most significant differences are as follows: “a rise of almost nine percent in the use of the present simple, from over 43 percent in the ‘World data’ to 53 percent in the ‘Shall-free data’”; e.g.: (96) Section 9 Every person shall have the right to life (Interim 1994). (97) Section 10 Everyone has the right to life (Constitution 1997). “A massive increase in the use of must, from just over three percent in the “World data” to well over 13 percent in texts where shall has been done away with; The use of may has risen in the ‘shall-free data’, up from over 13 percent in the ‘World data’ to over 18 percent; The semi-modal be to also has become more popular, from less than one percent in the ‘World data’ to more than four percent in the ‘shall-free’ data. In chapter three, author will examine the use of shall in her corpus and will analyze its translations into Polish. 31 Chapter 3: Modality in legal text translation – case study 3.1. Research questions In the research, the author wants to answer the following questions: Which legal texts contain more modal words: English or Polish? Which morphosyntactic categories are used most and least frequently to express modality (within the range specified in section 3.2.)? How each modal word is translated? Does it take the closest equivalent of the other language? Does shall appear in the examined English legal texts? If it does, how is it translated into Polish? (see section 2.5) These questions play a supporting role in finding similarities and differences in the overall characteristics of modality in Polish and English legal texts. 3.2. Methodology The author used LexTranslaide for conducting the research. It is a computer program which helps translators with their work by the means of translation memory (TM), glossary and automatic translation system. The most important tool for this research is the translation memory. TM is a perfect example of parallel corpora which is commonly used in computer assisted translation. TM of LexTranslaide consists of a number of legal texts including Polish penal code, Polish Constitution, rulings of the Constitutional Tribunal, various acts and newsletters, 500 sentences translated manually (court rulings and contract samples), 32 various reports and company agreements as well as bilingual corpus of the LEX Prestige program and materials from the Law Society website. TM is composed of 29039 sentence pairs, which comprise 737531 Polish words and 930468 English words. Polish legal texts contain 192937 words less than their English equivalents, which is baffling because it is usually the other way around. It may stem from the following reasons: The word count means the sequence of characters and since legal texts are known for many technical characters, such as article (§) which requires space between the article character and its number in Polish (§ 1) and does not require space in English (§1). This makes two words in Polish and only one in English. Legal texts which comprise the TM were originally Polish and translated into English. Bearing in mind intricacies of the law, translators could have translated the texts in a more descriptive way in order not to distort their meaning. Hence, there are more English words. In order to answer the research questions, the author typed in a modal word, e.g. modal verb ‘can’ in the TM search bar. The searching engine searched the TM and listed the translation units in which the searched word appeared. What is more, it listed each sentence/unit with its Polish translation in a separate column. Author believes that the following modal words are the most popular because most books listed in the references also relate to them. Therefore, these particular modal words should be used in this analysis as well. Verbs – ENG: must, can, should PL: musieć, móc, powinien Nouns – ENG: obligation, necessity, possibility PL: obowiązek, konieczność, możliwość Adjectives – ENG: obligatory, necessary, possible PL: obowiązkowy, konieczny, możliwy Adverbs – ENG: likely, possibly PL: prawdopodobnie, możliwie While searching the TM author encountered problems which sprang from the limitations of the LexTranslaide. The program does not take into account inflection of the Polish and English words. For this reason, it was necessary to look for each form of the word separately. Nevertheless, when searching e.g. ‘possibility’ and its plural form ‘possibilities’ one can enter only 33 ‘possibilit’ and the searching engine will list all units which contain both ‘possibility’ and ‘possibilities’ because ‘possibilit’ is the common part of both words. Moreover, one should be aware of the fact that the searching engine looks for the searched word also within other words, e.g. if we type in ‘can’ we will get words like ‘significance’ or ‘candidate’ among the results. In order to avoid such problem one must press space bar before and after the word he or she wants to search (e.g. space_can_space). In spite of the imperfections of LexTranslaide, it still serves as a valuable tool for the analysis, because unlike other programs e.g. Okapi Olifant, it has already a substantial inbuilt translation memory, so there is no need for providing legal texts in English and their Polish translations. What is more, LexTranslaide has a very useful function which allows its users to look for a specific translation of the searched word. The following example illustrates this function: if one types in ‘agreement’ in the English column and ‘umowa’ in the Polish column, program will display only those sentences in which ‘contract’ is translated as ‘umowa’. This function plays a significant role in the conducted research, as it makes it much faster and thorough. 3.3. Results of the analysis The conducted research answered the research questions and brought satisfactory results. Answer to each research question is provided in a separate subsection. Question 1: Which legal texts contain more modal words: English or Polish? Answer 1: As mentioned in the previous section, the author examined only selected modal words so the results are on the basis of the words in question only. Nevertheless, we need to take into account the fact that there are significantly more English modal verbs than the Polish ones. For this reason, ‘may’ (synonym to ‘can’, 4007 occurrences) and ‘shall’ (6538 occurrences) were also included in the total count of the modal words enumerated in 3.2. If they were not included the analysis would not reflect the reality, especially because these two English modal verbs are the most frequent ones. The final result is: 16793 modal words in the English legal texts which stand for around 1,8% of the total word count. Polish legal texts have 9772 modal words and that makes around 1,3% of the total word count. This means that English legal texts contain more modal words. Such result implies that Polish legal texts may have a slightly different interpretation than the English ones and the law 34 implications may also vary. One should also bear in mind the fact that there are other, nonmodal meanings of certain modal words, e.g. ‘can’ as in ‘a can of pepsi’ or ‘may’ as ‘May’ (the month). The author checked 50 random occurrences of these words and did not see any other meanings but the modal ones. Even if they happen to appear, the number of them should not be relevant enough to considerably affect the analysis. Question 2: Which morphosyntactic categories are used most and least frequently to express modality (within the range specified in 3.2.)? Answer 2: The most frequent modal form both in English and Polish are verbs. They constitute 85% and 71% respectively. The least frequent modal form, also in both languages, are adverbs. In English they comprise only 0,5% of all modal words and in Polish it is even less – 0,24%. Figure 1: Frequency of modal forms in English legal texts 35 Figure 2: Frequency of modal forms in Polish legal texts What might be interesting is the percentage of modal nouns used in Polish legal texts (21,45%). It is almost three times greater than in English legal texts – only 8%. The reason for it could be the fact, that most Adjectives seem to be also more popular in Polish (7,23%) than in English (6,5%). Question 3: How each modal word is translated? Does it take the closest equivalent of the other language? Answer 3: Table 1 presents four forms of modality (verbs, nouns, adjectives and adverbs) and their main representatives in English and Polish as well as their number of occurrences in the TM. The most important column is the ‘translation relation’ column. It informs about the number of exact translation of English modal words into their immediate equivalents in Polish (e.g. ‘must’ => P musieć). 36 Table 1: English and Polish modal words, their occurrences and translations Form of modalEnglish modal word ity Verbs Nouns adjectives Occurrences Translation- ENG/PL relation Polish modal word must musieć 1603/1116 831 can+may móc 5357/4936 3702 should powinien 794/894 272 obligation obowiązek 983/1331 539 necessity konieczność 47/190 28 possibility możliwość 272/575 194 obligatory obowiązkowy 34/122 13 necessary konieczny 698/430 298 possible możliwy 385/155 128 likely prawdopodobnie 65/6 3 possibly możliwie 17/17 3 adverbs It can be observed that in general the number of each modal word in both languages in question did not occur with similar frequency (e.g. ‘likely’ 65 vs. P prawdopodobnie 6). In the cases were the frequency of each pair of modal word was similar (e.g. ‘should’ 794 vs. P powinien 894) the number of exact translation those two words is still not significant. This may lead to conclusion that these words were either replaced by their synonyms or took different form of modality (e.g. a noun instead of a verb). Table 2 is very similar to Table 1 but it is balanced for the size of each side of the corpus, namely engsize = 930468 and polsize = 73753. Table 2: English and Polish modal words, their occurrences and translations English modal word Polish modal word must musieć 0.172279 1.513159 can+may móc 0.575732 6.692609 should powinien 0.085333 1.212154 0.105646 1.804672 0.005051 0.257617 possibility możliwość 0.029233 0.779629 obligatory obowiązkowy 0.003654 0.165417 necessary konieczny 0.075016 0.583027 0.041377 0.210161 obligation obowiązek necessity possible konieczność możliwy eng/engsize*100 pol/polsize*100 37 likely prawdopodobnie 0.006986 0.008135 possibly możliwie 0.001827 0.02305 After normalization with respect to the corpora sizes, frequencies of modals in both corpora can be compared by means of two-tailed hypothesis tests for paired samples. To choose the most appropriate test, the normality assumption needs to be examined. This is especially important in our case as the sample size includes only 11 cases. If the assumption will be met, parametric tests e.g. t-test for small samples can be applied. Otherwise, nonparametric tests should be used. Since standardized skewness and standardized kurtosis for (eng/engsize*100 pol/polsize*100) are both outside the range of -2 to +2 (-3.7 and 5.5 resp.), the sample significantly departures from normality, which invalidates any parametric tests. For this reason, only non-parametric tests will be used: paired sample sign test, signed rank test and paired sample Wilcoxon signed rank test. For all three tests the following assumptions were made: - Null hypothesis: median of eng/engsize*100 - pol/polsize*100 = 0 - Alternative hypothesis: not equal - Reject the null hypothesis for alpha = 0.05. Sign test Z statistic = 3.01511 P-value = 0.00256896 Signed rank test Z statistic = 2.8896 P-value = 0.00385742 Wilcoxon Matched Pairs Test Z statistic = 2.934058 Figure 3: Box and whisker plot for weighted pol and eng variables P-value = 0.003346 All tests tested the null hypothesis that the median (eng/engsize*100-pol/polsize* 100) equals 0 versus the alternative hypothesis that the median is not equal to 0. Since the p-value for all these tests is less than 0.05, we can reject the null hypothesis at the 95.0% confidence level. The analysis of Figure 3 reveals that the median of the variable 38 (pol/polsize*100) is significantly higher than the median of the variable (eng/engsize*100) for all 11 modals included in the analysis. Question 4: Does ‘shall’ appear in the examined English legal texts? If it does, how is it translated into Polish? Answer 4: Yes, ‘shall’ does appear in the examined English legal texts. What is more, it is actually the most frequent English modal verb (6538 occurrences). In order to see how it is translated into Polish author analyzed random 100 occurrences of ‘shall’ and its Polish translations. The most popular translation takes present simple form and constitutes 65% of the analyzed translations, as in: (98) The state shall exercise supervision over the conditions of work. P Państwo sprawuje nadzór nad warunkami wykonywania pracy. 18% of the translations were classified as ‘other’ by which author means phrases like P ma obowiązek, ma zastosowanie, jest wymagane and semimodal forms. For example: (99) The Chairman of the Supervisory board or a Deputy Chairman shall convene Board Meetings. P Przewodniczący Rady Nadzorczej lub jego zastępca ma obowiązek zwołać posiedzenie Rady. Modal verbs comprise 11% of the examined translations of ‘shall’. Most popular modal verbs in this case are P móc and powinien. For example: (100) Any statement of renunciation shall be made in writing. P Odstąpienie od umowy powinno nastąpić w formie pisemnej. The least frequent translation of ‘shall’ into Polish takes future simple form. Only 6% of analyzed occurrences had this form. For example: (101) The penalties shall be charged in the following circumstances… P Kary te będą naliczane w następujących wypadkach... Figure 3 presents the results: 39 Figure 4: Shall and its forms of translation into Polish 40 Conclusion The present paper attempted at analyzing frequency of modality in Polish and English legal texts as well as its distribution and forms of translation. For this purpose, definitions of key concepts (modality, legal language and legal texts) and their various aspects were discussed in the initial chapter. It has been shown that linguistic modality may ideally be interpreted as attitude the utterer/writer has toward what he or she is saying/writing. The second chapter focused on forms of expression of modality and demonstrated formal characteristics of Polish and English modal auxiliaries. Analysis of selected modal auxiliaries of both languages in question drew attention to possible problems translators may have when dealing with modal auxiliaries. The research contained in the final chapter, which was based on the parallel corpora of LexTranslaide has examined frequency of modality, its distribution and translation. It has turned out that the number of selected modal words in total word count in legal texts of both languages in question is very similar and verbs are the most frequent morphosyntactic category. The analysis has brought about starling conclusion, namely the number of Polish modal words which take their closest English equivalent of the same morphosyntactic category is insignificant. For this reason, the author beholds possibility for further research which would consist in analyzing what exact translations of each modal word are and what morphosyntactic forms they take. Finally, the analysis has negated null hypothesis which assumed that Polish legal texts use more modal words from the defined set than their English counterparts. 41 References Alcaraz, Varo and Brian Hughes (eds.). 2002. Legal Translation Explained. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing Ltd. Altay, Ayfey. 2002. Difficulties Encountered in the Translation of Legal Texts: The Case of Turkey. (http://accurapid.com/Journal/22legal.htm) (date of access: 23 Apr. 2010) Asprey, Michele. Shall must go. The Scribes Journal of Legal Writing, Australian Office of Parliamentary Counsel. 3/79: 79-83. Austin, John L.1962. How to do things with words. Oxford: Clarendon. Bhat, Shankara D.N. 1999. The prominence of tense, aspect, and mood. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. Greenberg Joseph. 1966. Language Universals: With Special Reference to Feature Hierarchies. The Hague: Mouton & Co. Harvey, Malcolm. 2002. What's so Special about Legal Translation?. (http://www.erudit.org/revue/meta/2002/v47/n2/008007ar.pdf) (date of access 21 Apr. 2010). Hiltunen, Risto. 1990. Chapters on Legal English. Aspects Past and Present of the Language of the Law. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia. Kahaner, Steven. 2005. Issues in Legal Translation. Ccaps Translation and Localization Newsletter. (http://www.gala-global.org/en/resources/CcapsKahaner_EN.pdf) (date of access: 23 Apr. 2010). Kakietek, Piotr. 1976. “Formal characteristics of the modal auxiliaries in English and Polish”. Poznań Studies in Contemporary Linguistics 4. Poznań: School of English, Adam Mickiewicz University, 205-216. 42 Kątny, Andrzej. 1980. Die Modalverben und Modalwörter im Deutschen und Polnischen. Rzeszów: Wydawnictwo Uczelniane Wyższej Szkoły Pedagogicznej w Rzeszowie. Kiefer, Ferenc. 1994. “Modality”, in Asher R. E. (ed.), The Encyclopedia of language and linguistics. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 2515-2520. Kratzer, Angelika. 1981.”The notional category of modality”, in Hans J. Eikmeyer and Hannes Rieser (eds.), Words, worlds, and contexts: New approaches in word semantics. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 38-74. Lauchman, Richard. 2002. Plain language: A handbook for writers in the U.S. Federal Government. (www.mindspring.com/~rlauchman/PDFfiles/PLHandbook.PDF) (date of access: 23 Apr. 2010). Loos, Eugene E. (ed.). 2004. Glossary of linguistic terms. SIL International. (http://www.sil.org/linguistics/GlossaryOfLinguisticTerms/contents.htm) (date of access: 21 Apr. 2010). Lyons, John.1977. Semantics. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Mowat, Christine. 1994. Buddhist, Running and Plain Language in Calgary. Parts One and Two. (July and August Issues) Michigan: Michigan Bar Journal. Mukhani, Al Yasser Salim Hilal. 2008. Modality in legal texts: an analytic study in translation between English and Arabic. Penang: Univeristi Sains Malaysia. Nida, Eugene and Charles R. Taber. 1964. The Theory and Practice of Translation. Leiden: Brill. Nyuts, J. 2001. Epistemic modality, language, and conceptualization: A cognitivepragmatic perspective. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. Palmer, Frank R. 1979. Modality and the English modals. London: Longman. Palmer, Frank R. 2001. Mood and modality (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Palmer, Frank R. 1988. The English Verb. London: Longman. Rowland, Tim. [n.d.] Propositional Attitude. (http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:vG9SCJg6mGkJ:www .icmeorganisers.dk/tsg24/Documents/Rowland.doc+All+utterances+encode+such+a+point+v iew,+and+the+description+of+the+markers+of+such+point+of+view+and+their 43 +meanings+is+a+central+topic+in+linguistics.&cd=1&hl=pl&ct=clnk&gl=pl) (date of access: 20 Mar. 2010). Stubbs, Michael. 1986. “A matter of prolonged fieldwork: notes towards a modal grammar of English”, Applied Linguistics 7(1): 1-25. Šarcevic, Susan. 1997. New approach to legal translation. The Hague/London/Boston: Kluwer Law International. PolEng, 2009. LexTranslaide. Version 7.0. Poznań: PolEng – Informatyka dla biznesu. Venuti, Lawrence. 1995. The Translator's Invisibility: A History of Translation. London & New York: Routledge. Williams, Christopher . 2009. Legal English and the modal revolution, in: Salke, Raphael (ed.), Modality in English, 199. “Linguistic modality”, in: State Master Online Encyclopedia (http://www.statemaster.com/encyclopedia/Linguistic-modality) (date of access: 19 Apr. 2010). 44