What are some alternatives for providing the educational support

advertisement

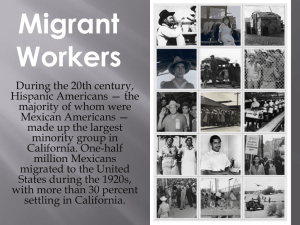

Case Study 2: Computer Assisted Learning in Migrant Schools Background What are some alternatives for providing the educational support that migrant students lack? Scrutiny of the international literature reveals that little is known about how to improve the quality of education for vulnerable children in developing countries in a cost-effective way. Worse still, a number of rigorous evaluations have demonstrated that spending more on inputs such as textbooks (Glewwe et al., 2002), flip charts (Glewwe et al., 2004) or additional teachers (Banerjee, et al., 2004) has little effect on children’s test scores (see Kremer, 2003, for discussions and more references). These results have led to a general skepticism about the ability of interventions focusing on inputs to make a difference and have led many to advocate more systemic reforms designed to change the incentives faced by teachers, parents and children. The World Development Report, once again, embraces this view, and proceeds to propose various ways to improve incentives (most of which have either not been rigorously tested or when tested, have also proven rather disappointing). One promising alternative to extracurricular tutoring and care is Computer Assisted Learning (CAL). If integrated CAL programs in schools are proven to effectively raise student performance inexpensively, we believe they be readily employed across wide areas of the nation’s school system. What is the basis for our optimism? In the early 2000s, a large-scale, rigorously implemented experiment in rural India’s schools demonstrated quite convincingly (in our opinion) that educational game-based computer assisted learning has the potential to drastically improve basic competencies among poor and underperforming student populations. The 2005 study found that students who participated in the CAL intervention improved their standardized math scores by 0.35 standard deviations the first year, and 0.47 the second year across performance levels. These results are outstanding, and far better than have been attributed to costly and complicated interventions such as reducing class size. In layman terms, the results from the India study show that after participating in the CAL program, a C+ student became a B student (while other C+ students who were not in the program made no improvement. What is more encouraging is that the study showed these results to persist over time—especially in student math classes. According to the study, students of all levels performed better in math if they were in schools where the math CAL program was implemented. These results suggest that it is possible to substantially improve the quality of education in developing countries with relatively inexpensive interventions, and do so in a way that makes a longterm difference in the lives of young students. This is based on Linxiu Zhang's case materials used in the SHIPDET Special Topic Courses on Impact Evaluation and Results-Based Planning and Budgeting held on 14-18 November 2011 in Shanghai, PRC. 1 An opportunity for IE Given this evidence, access to computers with innovative educational software may offer a viable alternative to the more conventional extracurricular care that so many migrant students lack. Providing such access could also be a way to help other groups of vulnerable and poorly performing students in remote rural communities. Unfortunately, China’s migrant students lack regular access to almost all forms of computing technology. Only 1 out of 20 migrant schools have functioning computing facilities. What is more, because the families of migrant students often live in poor, suburban villages (in houses of Beijing residents that rent their spaces out, often as they await the future demolition of the building), less than 10 percent of the children of migrants have access to computers in or near their homes. The promise of CAL to inexpensively deliver improved educational outcomes among migrant children is real, however, and deserves a proper evaluation. If found to be effective, a CAL program in China’s school’s could serve as a foundation for a new educational platform for helping children in other underprivileged areas of the country and the world. The proposed intervention: A research institute aims to test the potential for CAL programs to improve educational outcomes among migrant students in China. The proposed intervention is based on the premises that well-designed educational games can sustain interest and curiosity in an otherwise unsupportive school environment, and good educational software can be reproduced at nominal cost. The research institute will conduct a pilot project among fifth grade students in Beijing area migrant schools. Beginning in the first half of 2010(?), REAP will randomly select 50 schools to participate in a CAL intervention. After developing and testing a new educational games-based curriculum, in September 2010(?) the treatment schools will receive four high quality computers each. These computers will be “lent” to the school by the institute. Fifth grade children in each treatment school will be offered two hours of shared computer time per week. During this time they will play educational computer games that involve solving math problems at varying levels of difficulty (proceeding along with the curriculum). The games will be designed to emphasize basic competencies in these areas per the local curriculum. The student pairs will play the games under the supervision of a teacher for two hours per week outside of the school’s regularly scheduled classes (e.g., during the homeroom, study period; and during the lunch break). The institute will train the fifth grade schoolteachers in the migrant schools as the program’s manager. They will be responsible (with the project team’s aid) for scheduling students and monitoring their progress and keeping the computers running (by being in touch with an on-call repair team). Children will also complete simple worksheets designed to track their progress at the beginning of each session. During the first segment of the project, the institute will design the educational software program to allow the children to learn as independently as possible. The teacher- 2 supervisors will encourage each child to play games during their assigned time slots (e.g., 2 hours per week) and when necessary, help individual children understand the tasks required of them by each game. All interaction between the students and instructors are to be driven by the child’s use of the various games, and at no time will any of the instructors provide general instruction in mathematics or other subject areas. Group work 1. Map out a theory of change underlying your project (case study) 2. What are the related evaluation questions? 3. Sketch an IE design • Possible IE methods Propose for your intervention – Management structure (quality assurance) – Timeline for impact evaluation 3