Basics of CX Notes Plus

advertisement

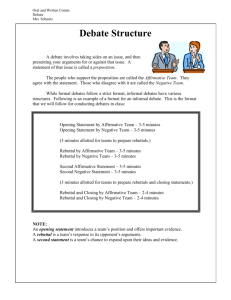

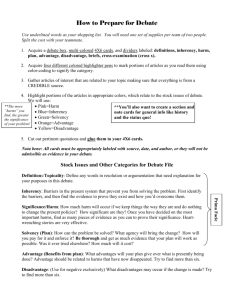

Basics of Cross Examination Debate Any discussion of cross examination (CX) debate must begin with the understanding that everything which goes on in a debate round is a part of the process of creative problem solving. Debaters should always keep in mind that debate is a process. While specialized terms have evolved in CX for specific types of arguments, debaters should always bear in mind that no matter what an argument is called it is only a part of a system or method of analyzing a problem or a solution for a problem. I. What We Debate In academic debate we are assigned a problem to analyze. In order to analyze the problem objectively, it must be worded in a way so that it is debatable or that reasonable people may accept arguments on either side. We call this type of statement a proposition or resolution. There are three types of propositions: 1) Propositions of fact. This is an objective statement that something exists or is true. The goal of the debater is to determine if the statement is, indeed, a fact. Examples: Resolved: that the earth is round. Resolved: that Lee Harvey Oswald was the lone assassin of John F. Kennedy. 2) Propositions of value. This type of proposition requires the debater to make value judgments about the qualities or desirability of some thing or issue. Propositions of value are the focus of Lincoln-Douglas debate. Examples: Resolved: that the rights of the individual are more important than the goals of society. Resolved: that justice should be the highest goal of a democratic society. 3) Propositions of policy. These statements generally focus on matters of public policy and require debaters to consider a course of action. These types of propositions form the basis of cross examination or policy debate. Examples: Resolved: that the United States government should adopt a policy to significantly increase political stability in Latin America. Resolved: that the federal government should adopt a policy to significantly decrease water pollution in the United States. 2 II. Key Concepts in Debate A. Sides. There are two sides in a debate--the affirmative and the negative. The affirmative has the duty of proving the resolution true and must present substantial reasons to support or adopt the resolution. The negative, on the other hand, has the duty of denying the resolution. The negative argues that the resolution should not be adopted. In many cases the negative may argue that the present system (or status quo) is adequate, that the solution offer by the affirmative will not solved the problem, that adopting the resolution would be disadvantageous, or that policies other than the affirmative’s proposal would better solve the problem. Debate teams must be prepared to argue either side of the proposition since most competitions require teams to switch sides during the course of the tournament. B. Stock Issues. The stock issues are a series of broad questions which encompass the major issues in any policy debate. These issues serve as a framework to define the problem to be solved and to analyze the solutions offered. 1) Significance. Is there a need for a change? The first step in the problem-solving process is to analyze and define what the problem is. Significance in a debate round does just that. It is the step during which the affirmative must prove that our present policies are harmful. There are two types of significance and both are generally documented during the debate. Qualitative significance defines exactly what harms are being created. Quantitative significance defines the scope of the problem by documenting how many are affected by the problem. 2) Inherency. This is the second step in the process. After defining what the problem is, the next thing debaters must do is explain why the present system cannot or will not solve the problem. There are three types of inherency which may be presented. Structural inherency is considered the strongest form of inherency. It documents that a law (or other barrier) exists which prevents the problem from being solved. Attitudinal inherency documents that prevailing attitudes among the congress or the population cause the problem to exist or prevent a solution to the problem. Existential, considered the weakest form of inherency, claims that the problem has always existed and will continue to exist unless the resolution is adopted. 3) Solvency. Once the affirmative has defined the problem and explained why it is not currently being solved, the next step is to offer a solution to the problem (referred to as the plan). They must then document that the plan will solve the problem(s) presented. This step is called solvency. 4) Topicality. This is usually considered to be the most important stock issue. Topicality simply means that the problem and solution offered by 3 the affirmative must fall completely within the scope defined by the resolution or topic. For example, if a resolution called for the government to reduce water pollution in the United States, an affirmative team which limited automobile exhaust in order to decrease air pollutants would not be topical since the resolution specifically calls for the affirmative to deal with water pollution. C. Other Important Issues 1) Presumption. We have incorporated in our justice system a concept known as the presumption of innocence, meaning that a defendant is considered to be innocent unless the prosecution can prove that his guilt. Debate incorporates a similar idea. Because any change creates a degree of risk, we assume that the system already in place should remain as it is unless there is a compelling reason to change. This is called presumption. The negative presumes that the status quo should remain as it is unless the affirmative can prove a need for a change. 2) The Burden of Proof. In order to overcome the presumption that things should remain as they are, the affirmative must provide a compelling reason to change the system. This is called the burden of proof. In order to meet this burden, the affirmative must present a complete analysis of the resolution in its case (a specific example of the resolution) which documents both the need for change and a workable solution. A case which meets this burden is considered to be prima facie (from the Latin, meaning "at first glance"). 3) Burden of Clash. Once the affirmative has presented a prima facie case, the negative then has the burden of clash. This means that the negative team's responsibility in the round is to directly refute the case presented by the affirmative. Negatives may choose to meet this obligation by directly attacking the arguments made by the affirmative or by showing the disadvantages of adopting the affirmative's proposal. But all negative arguments should relate directly to the affirmative proposal. 4) A Burden of Proof. While the affirmative must fulfill the burden of proof in order to overcome presumption, both sides have an obligation which is known as a burden of proof. This refers to the obligation to prove or document arguments or claims made in the debate. 4 D. Speeches Each speaker in the debate round is afforded the opportunity to speak two times. The initial speech for each debater is referred to as the constructive speech. The constructives make up the first four speeches in the round and are used to set forth the primary arguments to be advanced in the round. Each speaker also has a rebuttal speech. Rebuttal speeches should serve to clarify issues already presented in the round or crystallize important issues. New arguments should not be presented in the rebuttals, but new evidence and extended analysis of arguments already presented can and should be advanced in the rebuttal speeches. E. Time Constraints Most cross examination debate tournaments use the format generally referred to as "8-3-5." These are simply the time limits in the round. All constructive speeches in the round are 8 minutes, cross examination periods are 3 minutes, and rebuttal speeches are limited to 5 minutes. In addition to speaking time, each team is usually allowed 8 minutes of prep time. This preparation time is cumulative through the round. The round is structured as follows: 8 minutes--1st Affirmative Constructive (1AC) 3 minutes--CX of 1AC by 2nd Negative Speaker 8 minutes--1st Negative Constructive (1NC) 3 minutes--CX of 1NC by 1AC 8 minutes--2nd Affirmative Constructive (2AC) 3 minutes--CX of 2AC by 1NC 8 minutes--2nd Negative Constructive (2NC) 3 minutes--CX of 2NC by 2AC 5 minutes--1st Negative Rebuttal (1NR) 5 minutes--1st Affirmative Rebuttal (1AR) 5 minutes--2nd Negative Rebuttal (2NR) 5 minutes--2nd Affirmative Rebuttal (2AR) The combination of the second negative constructive (2NC) and the first negative rebuttal (1NR) is referred to as the negative block because the negative has back-to-back speeches which total 13 minutes. Because prep time is very limited, there are several ways teams can maximize the time they have available. First, if the partner of the person about to speak conducts cross examination, the speaker can use that time to prepare, providing an extra three minutes to prepare that does not count against prep time. The negative can also take great advantage of the time allotted during the block. Since the negative speakers generally divide the issues between them, the first negative can use the entirety of the 2NC and the following CX (a total of 11 minutes) to prepare the 1NR. 5 III. Constructing the Affirmative Case A. The Resolution The primary purpose of the affirmative case is to provide justification for accepting the resolution. The case and plan serve as an example of how the resolution can be implemented. Prior to writing the case, affirmatives should begin with an analysis of both the terms of the resolution and the issues related to the topic area. Since the affirmative has the burden of proof in the debate round, they also have the right to interpret the resolution (within reasonable limits). This interpretation is accomplished through the affirmative's definition of the terms of the resolution. While in the past it was common practice for the affirmative team to overtly define each term of the resolution in the first affirmative constructive speech in order to avoid any confusion, common practice today is to define the terms operationally. This means that the plan serves as an example of how the resolution will be implemented, and that the analysis of the issues serves to explain the affirmative's interpretation of the resolution. Examining the relationship of the words to each other as well as subtle differences in definitions of words can have a profound effect on the meaning of the resolution. For example, when debating the issue of scarce world resources, the definitions of scarce and resources determined what would be argued in the round. In the same vein, under the topic which required affirmatives to provide social services to homeless individuals, the relationship of the words to each other was critical. By defining social and services separately, a team might argue computer dating for the homeless would be topical since it was both social and a service. B. Structuring the Affirmative Case There are two primary affirmative case structures commonly used today. The first is a traditional type of problem-solution format called traditional needs. The other is a more contemporary policyoriented structure called comparative advantage. While there a subtle variations in the burdens involved in each format, it is important to note that the stock issues must be presented in each in order to be prima facie and overcome presumption. Traditional needs is the format many debaters grew up with. Its structure is as follows: Contention I. Significance The affirmative should explain and document the harms which are occurring in the present system. Contention II. Inherency The affirmative should explain and document what policies or attitudes in the present system are preventing the problem from being solved Plan--the affirmative must present a solution for the problem identified Contention III. Solvency The affirmative must provide analysis and documentation to prove the solution advocated will solve the problem 6 The comparative advantage format approaches the topic from a slightly different perspective. This organizational approach argues that any (topical) policy that is better than the present system should be adopted. The case is then formatted to show that adopting the policy would have advantages over the present system: Observation 1. Observation 2. Observations are usually general statements about the problem area which are important but do not readily fit into the analysis structured in the advantages. These are optional. Some cases will have one, others may have none. Plan--this format states the policy, then explains why it would be advantageous Advantage 1. The affirmative does something better than the status quo A. Significance B. Inherency C. Solvency Advantage 2. The affirmative does something else A. Significance B. Inherency C. Solvency This format allows the affirmative more flexibility in their analysis and justification of the topic. Most affirmatives will argue that if there is any advantage of the proposed policy over the present system, then it is a superior policy and should be adopted. In other words, when compared with our present system, if the new policy would be advantageous in any way, then it justifies adopting the resolution. An affirmative may present a number of advantages to the plan. Most cases debated today are hybrids which combine elements of both structural formats. Many begin with an inherency contention, followed by advantages, plan, and a general solvency contention. Regardless of the format selected, all cases must incorporate the stock issues in order to meet the affirmative’s prima facie burden. C. The Plan The plan is the affirmative’s proposal (or policy) to solve the problem(s) identified in the case. Traditionally, the plan was divided into different segments called planks which included details in support of the policy proposed by the affirmative. The planks included: 1. Mandates—the policy (or legislation) proposed by the affirmative. 2. Administration—specifies an agency or administrative procedures that will oversee the implementation and functioning of the mandates. 3. Funding—explains where any money necessary for the plan will come from 4. Enforcement—explains how violations of the plan will be dealt with or who will be charged Current practice in competitive debate is to present just the basics of the mandates. Strategically, this practice avoids some potential negative arguments. However, even though this has become common practice, affirmatives may still be required to be able to defend all of the traditional plan requirements in any given debate round. 7 IV. The Negative Constructives A. The First Negative ( 1NC ) The current practice in debate is to present the entire negative strategy in the 1NC. The shells or (prepared basic arguments which include the evidence and all necessary structural elements for the argument) for all primary arguments to be advanced by the negative team are presented in the first constructive and further developed in the negative block. 1) Topicality. The first issue usually addressed by the negative is topicality. The negative must either accept or reject the affirmative definitions of the resolution. If negative believes the affirmative has been unreasonable in their interpretation of the topic, they may challenge this in the form of a topicality attack. a) There is a specific format and structure which must be used in a topicality argument: A. Definition—the negative reads a definition of a term in the resolution which they believe the affirmative violates B. Violation--explains how the affirmative does not meet the definition established. C. Standard--establishes criteria for evaluating topicality. Some common standards are: A. Reasonability B. Better definition (we should accept the better definition offered in the round) --legal definition --contextual definition --field definition --dictionary definition C. All words have meaning (every word in the resolution is important) D. Limits (it is necessary to set limits on the scope of the topic) E. Ground (the definition divides affirmative and negative ground more equitably or clearly delineates aff and neg ground) F. Brightline (definition draws a clear distinction between what is topical and what is not topical) G. Predictability (definition increases the education in the debate because it provides a definition under which the negative can reasonably predict and prepare for a limited number of affirmative cases) (The negative should not only present a standard, but should give analysis on why that should be the accepted standard.) 8 D. Impact (or Voters)--the negative should explain the importance of the issue and explain why topicality is a voting issue. Some criteria for voting on topicality include: A. Jurisdiction--argues that topicality is an a priori issue (the top priority) because if the affirmative is not topical, then the judge has no jurisdiction over the issue and cannot vote for the plan B. Educational value C. Fairness—gives both sides an equal opportunity to win the the debate round D. Games theory--argues that all games have rules, debate is a game, and topicality is one of the rules of the game b) Other topicality issues Effects topicality--an affirmative is effects topical if the plan does not directly implement the resolution. In other words, the plan sets events in motion which eventually lead to a policy which incorporates the resolution. The negative stance on this issue is that topicality must be the first issue decided. A case which is effects topical must prove solvency before topicality can be proven, but solvency becomes irrelevant if topicality is decided first. Extratopicality--extratopical advantages go beyond what is required by the resolution. For instance, an advantage which claims to solve the national deficit as a result of money left over from the plan funding would be extratopical because the funding mechanism does not implement the resolution. 2) Disadvantage--this argument claims that adoption of the plan would cause more harm than good. Requirements of the disadvantage: A. Uniqueness--the negative must show that the disadvantage is unique to the affirmative (If the harm is occurring now, the affirmative cannot be held liable for it. The disad may, however, be linear. This means that the affirmative makes a current problem worse.). Uniqueness evidence usually indicates that, absent the affirmative plan, the impact will not happen in the status quo. Some disads may include a brink (which argues that we are okay right now, but that we are on the brink of crisis and any push will send us over that brink). 9 B. Link--the negative must show the specific affirmative action which causes the impact to occur. C. Impact--the harms which would occur if the plan were to be adopted An important consideration when arguing disadvantages is the relationship between disads and other arguments in the round. Since many links to disadvantages are generically related to the topic, many negative arguments (like counterplan and critical arguments) may also link to the disadvantages and create strategic problems for the negative. 3) Counterplan--an advanced negative strategy which offers a nontopical alternative to the affirmative plan. The negative admits that the status quo is flawed, and offers a competitive alternative. Current debate theory puts less emphasis on topicality of the counterplan and more emphasis on the competitiveness. Criteria for a counterplan: A. Non-topical—the negative usually explains why they violate one of the terms of the resolution. Although this is a traditional requirement, many counterplans today are topical and rely on competition to distinguish them from the affirmative plan B. Competitive--method of weighing the affirmative proposal with the negative counterplan. To be competitive, the negative must achieve the same advantages as the affirmative and/or be mutually exclusive (cannot coexist) C. Net beneficial--since the negative must give up presumption, the counterplan must be more advantageous than the affirmative plan (this is usually done by showing how the counterplan will avoid the disadvantages associated with the affirmative plan) Many counterplans today are considered to be “plan inclusive” or PICs. These counterplans may do all of the affirmative plan except one thing, or may do plan along with another action. Counterplans can be run in different ways. They may be offered in the round as unconditional (meaning that the negative will advocate the policy of the counterplan throughout the round), dispositional (the negative may disregard the counterplan after responding to turn arguments), or conditional (the negative offers the counterplan as a test of the resolution and is not bound to advocacy of the counterplan; the negative may advocate the policy or jettison the counterplan at any time). 10 4) Kritik (or Critique)—this is an advanced negative strategy which attacks the philosophical assumptions of the affirmative case; usually argues that we need to rethink our approach to specific ideas, language, or actions (Note: This type of argument is theoretical in nature and, although gaining more widespread acceptance, may not be accepted as legitimate argumentation by many judges. You should usually ask the judge’s philosophy about critical arguments before the round begins.) General requirements for a kritik: A. Link—what action the affirmative takes that is objectionable (or objectionable language used) B. Implication—explains the philosophical mindset violated by the affirmative and why violating it is bad C. Alternative—explains how we can rethink or take alternative action to avoid the implications of the kritik (Not all kritiks have alternatives; some are nihilistic in nature, just questioning our motives without taking action. However, many judges will find a kritik unacceptable if there is no alternative.) Note: It is important to note that a kritik asks the judge to change the way he/she views the round. It sets the stage to examine the debate from different world views or means of evaluating the round. Normally, a team that runs a kritik will not run a counterplan (especially a plan-inclusive counterplan) at the same time. To do so would risk contradicting the philosophy, worldview, or the mindset established in the kritik. This is a unique kind of contradiction called a performative contradiction. For instance, if a team ran a kritik which argued that we must reject any language of nuclear weapons or nuclear war because any discussion which includes scenarios for nuclear war makes such a strategy more likely and moves the world closer to apocalypse and then presented a disadvantage with a nuclear war impact, they would be guilty of violating the standard they established in the kritik. 5) Other first negative strategies Workability--this usually deals the structure of the plan itself and argues that the plan is not a workable piece of legislation. Straight refutation--this is a less commonly used first negative strategy. The negative speaker goes through the affirmative case and refutes it directly point by point. This may be done by showing flaws in the affirmative argument or evidence or by providing a counter-argument and counterevidence. Defense of the status quo--the negative either claims that the 11 present system is sufficient to solve the problem or that the plan already exists in the status quo. Solvency—the negative presents arguments explaining that the affirmative plan will not solve the harms cited. Solvency attacks may include arguments like alternate causality (that many other things contribute to the problem which will prevent the plan from solving), circumvention (ways people can get around the plan), or case turns (which show how the plan will actually make the problem worse). B. The Second Negative Constructive ( 2NC ) 1) The second negative is usually a specific argument specialist. The 2NC normally becomes a specialist in two or three specific arguments which can be run against a variety of cases on the topic. The shells of those arguments are presented in the 1NC and then extended and expanded or ballooned by the 2NC. The other arguments will then be covered and extended in the 1NR. 2) Argument selection is one of the most critical parts of the 2NC. The negative team must determine which arguments will be covered by each speaker in the negative block. The second negative also has the responsibility of selecting which arguments the team will use in the last negative rebuttal to justify the win. V. Speaker Responsibilities 1st Affirmative Constructive--The primary responsibility of the 1AC is to present a prima facie case for the resolution. It should cover all of the stock issues and provide a plan to solve the problems or harms cited. 1st Negative Constructive—The primary arguments the negative plans to advance in the round will normally be presented in this speech. Types of arguments presented in this speech usually include: 1) Topicality--if topicality is to be contested, it should be presented in this speech. Since most negatives argue that it is an a priori issue which must be decided first as well as a prima facie issue, it should be one of the first arguments presented by the negative. 2) Direct refutation--point-by-point refutation of the affirmative. It is here that the negative usually tries to take the offensive away from the affirmative and expand the debate. 3) Counterplan--if the negative chooses to use this strategy, it should be presented in this speech. Since a counterplan is a major policy objective, it should be advanced early in the round. It should be noted that the negative must give up the advantage of presumption and admit a major flaw in the present system in order to offer a counterplan. It is also important to note that the counterplan is not a panacea for teams who do not like research 12 and do not like to debate on the negative. The purpose of a counterplan should not be to avoid clash in the round; rather, counterplans should be utilized primarily in those cases where a non-topical alternative would provide a better policy. 4) Disadvantages--this is the primary weapon of the 2NC. The purpose of the disad is to show that the risk of the disadvantage harms outweighs any advantage the affirmative might accrue with their plan. 5) Solvency—shows why the affirmative plan cannot solve the harms addressed. 6) Kritik—argues that the philosophical assumptions in the case are objectionable 2nd Affirmative Constructive--The primary goals in this speech are to return the affirmative to the offensive, to uphold the affirmative's burden of proof, and to narrow the focus of the debate. In order to do this, the affirmative must refute the 1NC arguments: 1) Respond to any topicality attacks and show why the affirmative case meets the disputed terms. 2) Refute any attacks made on case structure. Be sure to follow the structure set up by the case in 1AC. 3) Answer solvency attacks using the structure set up in the 1NC. 4) Respond to disadvantages 5) Refute any other attacks, including counterplans and kritiks, made by the 1NC. A counterplan may be refuted in a number of ways. Basically, the affirmative may prove that it does not meet the criteria established for a counterplan (non-topicality, competitiveness, etc.), that it is not a superior policy, that it would fail to solve the problem, or that it would be disadvantageous (Yes, you can run disads against a counterplan. Just make sure they don't also link to your own plan.). Currently, a popular negative strategy is to present some disadvantages in the 1NC. If this is the case, they must be refuted in the 2AC. 4) Extend on arguments presented by the 1AC. 5) Explain why the affirmative case is still advantageous when compared with the status quo. 13 2nd Negative Constructive-- 2NC is the first speaker in the negative block, so strategy for this speech should be centered around the combination of speeches. Strategy for the second negative might include: . 1) If 1NC runs disadvantages, 2NC then has the option of "ballooning" (refuting arguments and massively extending) a disad or handling case refutation. 2) Any major negative arguments which have not yet been addressed must be set forth in this speech prior to rebuttals. 3) New arguments (not set forth in the 1NC) are normally presented in this speech only if the analysis or advocacy by the affirmative shifts in the 2AC. 4) The 2NC and 1NR should coordinate and divide the arguments to be covered between the two speeches. 1st Negative Rebuttal--This is the first rebuttal speech and the second half of the negative block (since the affirmative had the burden of proof, they have the privilege of speaking first and last in the round). This speech forms a critical juncture of the negative strategy in the debate round. It is essential that the team members coordinate their efforts for the negative block. If the 1NR simply repeats the arguments made by 2NC, the advantage of this block of time will be wasted. Some of the options for the 1NR include: 1) It is important to note here that while in the rebuttal speeches debaters may not advance new arguments which have not been previously tenured in the constructive speeches, debaters can and should give new evidence and new analysis on arguments already advanced in the round. 2) If 2NC balloons an argument, the negative speakers need to divide the responsibility and discuss ahead of time which arguments will be handled by the 1NR. 3) The primary strategy of the negative block is normally to place the burden of having to cover several crucial arguments in a short time period on the 1AR. 1st Affirmative Rebuttal--Since the 1AR has to refute the negative block, it is the most crucial speech in the round. It is here that most debates are won or lost. Some basic 1AR strategies include: 1) Prioritize arguments. Since time is so limited, the 1AR must cover the most critical arguments first. The typical rebuttal priority is topicality, counterplan or kritik (if presented), disadvantages, solvency, then case. 2) Consolidate as many arguments as possible. Look for the easiest way out of arguments--point out fallacies in reasoning and missing links in arguments; where possible try to show how negative disadvantages actually create affirmative advantages (turns); extend 2AC arguments that the neg has failed to respond to. 3) Rebuild affirmative case at major points of attack. It is important to finish the 1AR with the stock issues intact. 14 4) Maintain the offensive by showing why the affirmative case is still advantageous when compared with the status quo 2nd Negative Rebuttal--This is the negative's last opportunity to show why they should win the round. Arguments should focus on critical issues in the round. Strategy for this speech usually includes: 1) Re-establish major negative arguments. Show why disads still apply and outweigh case advantages; establish important arguments dropped by the 1AR; reestablish negative arguments against case. 2) Since time is limited, 2NR should focus arguments on issues important enough to win the round. Summarize these issues and show why the negative should win them. It is also important to show why those issues justify the ballot. 3) Normally, the 2NR will select a few critical arguments which can be used to justify the ballot and explain each argument carefully, why the negative wins those arguments, and why the judge should vote on those issues. 4) Summarize and conclude, calling for the rejection of the resolution. 2nd Affirmative Rebuttal--This is the affirmative's last opportunity to show why they win the round and justify the resolution. 2AR strategy is usually relatively basic--paint a pretty picture: 1) Review the plan objections taking special care to refute major disadvantages, especially those covered by 2NR. 2) Try to focus the debate on three or four major arguments on which the affirmative case depends, showing how the affirmative wins those critical issues. 3) Review the basic affirmative analysis which shows that at the end of the round, the affirmative still maintains an advantage over the present system and call for the acceptance of that analysis and the resolution. 15 Topicality Negative Affirmative A. Definition --read a definition which you can argue that the affirmative doesn’t meet Affirmative answers to topicality: B. Violation --explain why the affirmative doesn’t meet the definition 1. “We Meets” --explain why the affirmative actually meets the negative definition (try to give at least one or two reasons why the affirmative meets the negative’s definition) C. Standards --how we should evaluate competing interpretations (What is the best means of looking at the topic?) Some standards include: --contextual (how experts in the field interpret the meaning of the word) --limits (because the negative has limited prep time and can’t possibly prepare for every conceivable case, the interpretation which most limits the topic is the best interpretation) --predictability (again, neg can’t prepare for everything, so the most predictable interpretation is the best to promote fairness and education in the round) D. Voters (Impact) --gives reasons why the judge should vote on topicality Common voters: --jurisdiction (the judge may only vote for affirmatives which fulfill the mandates of the topic; anything else is outside the judge’s jurisdiction) --fairness (both teams should have an equal opportunity to win the round) --education (an unpredictable affirmative that the neg has no answers for does nothing to make debate an educational experience; learning 1 issue indepth is far more educational than learning 1 minor fact about 10 issues) 2. Counter-definition --read your own definition of the term in question (make sure you actually meet the definition) --explain why your case meets this new interpretation 3. Counter-standard --present a standard more appropriate for the affirmative Example: Reasonability—the affirmative’s only responsibility is to be reasonable in its interpretation of the resolution; I.E., Would a reasonable person accept the affirmative’s interpretation of the topic? --explain why the affirmative meets the counter-standard 4. Topicality is not a voting issue --explain why the judge should not vote on topicality 5. Answer the negative arguments line-by-line Example: --general definitions are better than contextual because they are more widely understood; general definitions make the debate more predictable --limits are bad because the negative overlimits the topic; over-limiting decreases education; violates the affirmative right to interpret the resolution, etc. 16 Disadvantages Negative Affirmative A. Uniqueness Answering the disadvantage --explains why impacts are unique to the affirmative plan; the system is okay right now [which means that the affirmative plan is what causes the bad things or impacts to happen] 1. Non-unique --proves the affirmative is not responsible for the impacts B. Link --what action the affirmative plan takes which causes the impacts to happen Example: --affirmative passes environmental regulations and environmental regs are expensive for businesses to implement them, decrease profits, increase inflation, etc., which destroy business confidence or damage the economy C. Impact --the bad things which will occur as a result of implementing the plan Example: --plan destroys the US economy; US economy keeps world economy afloat; global depression will result in World War Examples: --economy is cyclical in nature, it goes up and down all the time; therefore impacts should have already happened; aff isn’t responsible --other factors affect the economy 2. No link --proves that the affirmative doesn’t connect to the impacts; aff action is not responsible for the chain of events 3. Turn --shows how the affirmative actually solves for the impacts of the disadvantage or that the status quo is actually responsible 4. No impact --explains why impacts won’t actually happen; why they should have already happen if the neg is correct or that the impacts won’t be as bad as the neg claims 5. Case outweighs --explains why solving for case harms is more important or why the advantages outweigh the impacts of the disadvantage 17 Counterplan Structure 1. Counterplan text. Just as the affirm has plan text in their case, the negative CP must also have plan text which states precisely the action of the counterplan. 2. CP is nontopical (if applicable). Explains how the counterplan violates one or more terms of the resolution. 3. CP is competitive. Explains why the judge is forced to make a choice between the plan and the counterplan. 4. CP is net beneficial. Explains why the counterplan is a better policy option than the affirmative plan. This will usually be an explanation of how the affirmative gets disadvantages that the counterplan avoids. 5. CP solvency. Just as the affirmative must provide evidence to prove that plan will solve the problems addressed, the counterplan must also have solvency evidence to prove that the CP mechanisms will solve the problem. 18 Counterplan Theory Notes Beyond the traditional theoretical requirements of a counterplan (nontopical, competitive, net beneficial), there are a number of debate theory implications related to counterplans: 1. The status of the counterplan. [This should be the first question the affirmative asks about the counterplan during CX.] Depending on the degree of advocacy by the negative, the counterplan may be presented as: a. unconditional—the negative is committed to this policy position throughout the debate. The negative cannot revert to the status quo. b. dispositional—the negative may kick out of advocacy of the counterplan if the affirmative presents theoretical objections (perm or competitiveness), but cannot kick out of the counterplan if it is turned. c. conditional—negative has the option of jettisoning the counterplan at any point in the round. They do not have to advocate a conditional counterplan. You will need theory briefs on why dispositional and conditional counterplans are bad and why they are good. 2. Counterplan topicality. Traditionally, counterplans are nontopical alternatives to the affirmative plan. However, current trends in debate allow for counterplans to be topical as long as they are competitive and net beneficial. The reasoning behind this is that debate is inherently biased toward the affirmative since they have an infinite amount of time to prepare their affirmative arguments. The affirmative does not defend the entirety of the resolution; they pick an example of the resolution. Hence, the focus of the debate is the plan and not the resolution. Once the affirmative presents their advocacy (plan), they must be prepared to defend the entirety of the plan. This theory allows counterplans which include all or part of the affirmative plan. This is called a plan-inclusive counterplan or PIC. You will need theory briefs on why PICs are good and why they are bad. 3. Permutations (or perms). The permutation is an affirmative answer to the counterplan. It is intended to be a test of competitiveness. A perm argues that if you can do all of the plan and all or part of the counterplan at the same time, then the counterplan is not competitive (i.e., it does not force a choice and is, thus, not a reason to vote against plan). In some cases, the counterplan permutation may provide an offensive argument for the affirmative. 19 There are several types of perms: a. Pure permutation: advocates all of plan and all or part of the counterplan. b. Timeframe permutation: advocates doing one or the other first. c. Severance permutation: does not include all of plan (i.e., leaves a word or action out). This type of perm is sometimes used to prove that the counterplan is abusive to the affirmative. d. Intrinsic permutation: makes an addition to plan. Intrinsic perms add something that does not exist in either the plan or the counterplan (i.e., do plan and counterplan and have US and Japan act cooperatively in response to a Japan counterplan). You will need briefs on why each of these types of permutations is or is not legitimate. 20 Basic Kritik Theory Notes Although more widely accepted in high school debate today than just a few years ago, the kritik is still a controversial argument in policy debate because it generally indicts underlying assumptions in or of debate rather than actual policies. Kritiks may question certain mindsets, beliefs, practices or actions. They hold that the way we think is more important than the end or goal of our thought. A. Requirements for a kritik While there are no specific rules or requirements for kritiks, as practiced in debate today, the structural elements which should be included in a kritik are: 1. Link—what the opposition does that is objectionable. This could be: --use of objectionable language --use of arguments based on incorrect assumptions --use of arguments which entrench objectionable thought 2. Implication—explains why the action is objectionable (should include evidence and analysis. This is, essentially, the impact of the kritik. 3. Alternative—how we should act or think in order to avoid the implications of the kritik. a. Alternative may be in the form of a counterplan, different mindset, or a specific action or inaction. b. Not all kritiks have alternatives; some just question. B. Common categories of kritiks. 1. Thinking—challenge the way participants construct or systemize reasoning These kritiks may challenge things like rational thought or world view. 2. Rhetoric and/or language—attacks the opponent for using words or language in a harmful way 21 Examples: Gender language kritiks argue that using sexist language (human, mankind, etc.) entrenches or reinforces a dangerous patriarchal mindset. The nuclearism kritik argues that talking about nuclear war scenarios desensitizes part of our culture to the horrors of nuclear war and thus makes such a war more likely. 3. Values—identifies and attacks ethical or moral beliefs behind what debaters say or do. Example: The statism kritik argues that the framework of the “state” is by its very nature oppressive and that any action taken by the state entrenches oppression. (The alternative to this kritik is anarchy.) 22 Answering Kritiks 1. No link. Explain why the actions or mindset of the plan do not link to the kritik. 2. Permute. Kritik is not mutually exclusive to the plan. We can think about “x” then do plan. Kritik is not a reason to reject the affirmative. 3. Turn. Plan is a step in the direction of the kritik. Plan serves as a springboard for the kritik because it focuses attention on the kritik issues. 4. Counter-kritik. A kritik may be infinitely regressive. It only deconstructs ideas and ignores real world issues. Instead, we should adopt an alternative mindset advocated by the affirmative. --pragmatism --deontological vs. consequentialism --capitalism vs. communism 5. Performative contradiction. Negative advocates an action, mindset, or language that violates their own kritik. Examples: Negative runs a nuclearism kritik (arguing that discussing scenarios for nuclear war desensitizes us to the real horrors of nuclear war, making the unthinkable doable) and then runs a disadvantage with a nuclear war impact. Negative indicts the affirmative mindset and then runs a plan-inclusive counterplan. 6. Direct refutation of kritik philosophy. 23 Common CX Debate Terms Advantage—benefits resulting from the adoption of the plan Affirmative—debate position in favor of the resolution Assertion—an unsupported statement Block—arguments and evidence organized to refute a specific argument Bright Line—topicality standard that suggests the best interpretation of a term establishes a clear boundary between what is topical and nontopical Brink—level of change needed to cause an impact or harm to occur Burden of Clash—responsibility of the negative to respond directly to the arguments presented (A) Burden of Proof—burden all debaters have to prove their arguments through analysis and evidence (The) Burden of Proof—responsibility of the affirmative to prove a compelling reason to change the status quo in order to overcome presumption Claim—the part of an argument that states the conclusion a debater wants the judge to accept Clash—to directly respond to an argument Competitive—forces the judge to make a choice between two alternatives Constructive—first speech given by a debater; establishes the key arguments in the debate Counterplan—a negative alternative to the plan Cross apply—applying arguments made on one issue to another Cross examination—period during which questions are asked and answered Disadvantage—a harm resulting from the adoption of the plan Drop—to fail to address an argument or object of discussion Effects topicality—negative argument that claims the affirmative plan does not directly implement the resolution; rather, filling the requirements of the resolution is an eventual effect of the plan Evidence—all printed material used as reference and support material in debate Extend—to take an argument given in a previous speech and add depth to its analysis Extratopical—gaining an affirmative advantage through mechanisms other than those required by the resolution 24 Fiat—implied power to put the plan into effect (the affirmative doesn’t have to prove that the plan would be adopted, only that it should be done) Impact—ultimate consequence of an action Indict—to find fault with Inherency—the barrier that keeps the status quo from implementing the plan Kritik—argument that indicts or questions our underlying assumptions Linear disadvantage—argument that claims the affirmative makes a current problem worse Negative—side in the debate that argues against the resolution Negative block—combination of the 2nd negative constructive and 1st negative rebuttal when the negative team has back-to-back speeches in the round Overview—analysis given prior to specific arguments which explain the implications of the argument Paradigm—a perspective or guiding philosophy from which a judge evaluates arguments Permutation—test of counterplan competitiveness that argues both the plan and counterplan can co-exist; captures the offense of the counterplan by proposing to do both Plan—affirmative’s specific proposal to put the resolution into effect Presumption—assumption that the status quo should remain the same unless the affirmative can prove a compelling reason to change Prima facie—Latin term which means “first glance”; in debate it refers to a case that meets all of the stock issues; a prima facie case overcomes presumption Proposition—a statement worded in such a way as to be debatable Qualitative significance—proves that some harm exists in the present system Quantitative significance—a measurement of the harms in the present system Rebuttal—second speech given by a debater designed to crystallize issues already presented in the constructive speeches Refutation—evidence and arguments that deny the validity of the opponent’s position Road mapping—giving the judge indications as what part of the debate the debater is going to next; the order in which the debater will cover the arguments; aids in flowing. Shell—a block usually read in the 1NC which contains all of the structural requirements of a specific argument Significance—the importance or scope of an issue; claims that harms are occurring in the status quo 25 Slug (or tag)—a name or label for an idea Solvency—stock issue that proves the affirmative plan can solve the problem or gain the advantages claimed Standard—criteria for evaluating an issue Status quo—the present system or current way of doing things Stock issues—series of broad questions which encompass the major issues in any policy debate; includes inherency, significance, solvency and topicality Tag—short summary of the argument presented in a piece of evidence Topicality—burden of the affirmative to meet all of the terms of the resolution Turn—proving that an opponent’s argument has the opposite impact of what was intended Uniqueness—the “inherency” of a disadvantage; proves that the impacts of the disadvantage are caused by the action of the affirmative Warrant—support for a claim Workability—the ability of the affirmative plan to function