MRenglish

advertisement

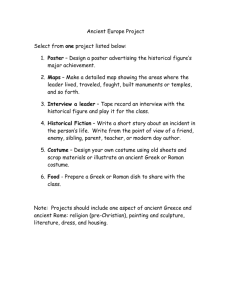

FRENCH MILITARY RECONNAISSANCE

IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE (18th & 19th CENTURIES)

AS A SOURCE

FOR OUR KNOWLEDGE OF ANCIENT MONUMENTS

Introduction

The nations of Europe have derived strength and security from the general

improvement of human reason, and the cultivation of the arts of peace and war;

in the meantime, the spirit of military enterprise has declined among the Turks;

the vigorous age of their monarchy is past; and the weakness of their empire has

been exposed to their enemies, and parts of it have been invaded, or wrested

from them1

Since the fall of the Roman Empire, the military have seized upon the

possibilities offered by various kinds of antique structures for defence, or for

their materials for dismantling and rebuilding. We owe the survival of theatres

and amphitheatres all over France, or temples in Turkey and the Lebanon, to

their re-use as fortresses, and our knowledge of ancient sculpture and

architecture often depends upon the reuse of ancient blocks in new structures,

as at Pergamum or Koykos (Turkey). When the European military sought

intelligence on the ottoman Empire, it was therefore inevitable that they should

view any structures which might prove useful to them both for military ends, and

to amplify their usually assiduous interest in the antique past, the product of

a classical education. This paper examines the French military attachment to

antique remains and their reuse - spolia - as an important aspect of the

developing interest in Greek and Hellenistic art and architecture from the late

18th century onwards. Indeed, the acceptance by the French Ministry of War of

“archaeological asides” in large quantities in the reports they received is a

reflection not only of how the fabric of Antiquity was still in use in the

Ottoman Empire, but also of how the practical and the antiquarian are often

indissolubly mixed in the reports the officers sent back. For scholars today,

the reconnaissance reports filed in the Archives de la Guerre at Vincennes

(Service Historique de l'Armée de Terre) provide assessment from frequently

knowledgeable officers of many monuments which have either disappeared

completely over the past two centuries, or have been radically altered.

The very size of the Ottoman Empire dictated the spread of French interests in

war materiel and fortifications from the Greek Islands and the Balkans to the

Black Sea, and from Eastern Turkey down into Syria - and hence the range of

Greek and Roman antiquities of which the French were to offer accounts. Of all

European powers during the 17th and 18th centuries France had the strongest trade

interests in the Levant - from the Balkans and Greece, through Syria, Egypt and

Tripolitania to Algeria and Tunisia - and used her navy and her military

Rev. Robert Walpole, Memoirs relating to European and Asiatic Turkey, edited

from manuscript journals, London 1817. Preliminary discourse on The Causes of

the Weakness and Decline of the Turkish Monarchy, p.1.

1

1

readiness and reconnaissances in order to protect them2. An ally of the Ottoman

Empire since 1535, French trade with that immense concatenation of countries

comprised some 50% of all her maritime trade. By the French Revolution, only

Spain and America were more important markets for her, and half the trade

between Europe and the Ottoman Empire was in the hands of France3. Like other

European powers, France wished to maintain the integrity of the Ottoman Empire

because it was not in her interests to see it divided. France's premier position

was maintained by a varied mixture of diplomacy4, agreements - the capitulations

- and the threat of force; and the Ottoman Empire was a useful weapon against

Russia and Austria. With Napoleon's invasion of Egypt in 1798 that threat became

a reality, subdued by the ignominious retreat and then enhanced by the designs

on the rest of Europe which unhinged the balance of power and presented Turkey

and the Balkans as a likely theatre of conflict between France and Russia. What

is more, Napoleon's actions, frequently contradictory and against traditional

French loyalties, achieved the otherwise difficult task of throwing Russia, long

the Ottoman Empire's enemy, into alliance with her5. The Levant, in other words,

was to become in the 19th century the target of the expanding empires of Britain

(Egypt) and France (Algeria and Tunisia), whilst the long-brewing conflict with

Russia came to a head in the Crimea.

During the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, Ottoman military and technological

skills declined, forcing her to employ temporary consultants from the West for

such tasks as cannon-founding, fortress-building, the production of gunpowder

and the training of troops in modern warfare and the use of modern small arms.

Thus 15 artillery experts are listed for payment in the budget for 15276; the

French Ambassador himself trained Ottoman artillery for the Russian War of 154850, and established naval operations against Spain in 1551-57; and French

embassies offered aid in the 17th century. The Embassy of Mehmed Efendi to

France in 1720-21 included military manoeuvres as well as the study of

fortification models8; and the series of military reverses the Ottoman Empire

suffered in the 18th century occasioned new efforts at military reform and

modernisation, such as the introduction as late as 1807 of training in European

fighting techniques mainly by France, but also by Britain, Sweden and Austria.

Foreign military aid continued, with Russian, Prussian and British military

missions in 1834 - too late, since her defeats triggered the Eastern Question,

namely the long agony for the dismemberment of the Empire which concluded with

the Treaty of Lausanne in 19239.

P. Masson, Histoire du commerce français dans le Levant au XVIIe siècle, Paris

1896; ibidem, Histoire du commerce français dans le Levant au XVIIIe siècle,

Paris 1911;

3 P. Mansel, Constantinople: city of the world's desire, 1453-1925, London 1995,

p. 114;

4 cf. A. Vandal, Les voyages du Marquis de Nointel (1670-1680), Paris 1900,

pp.1-21: "Louis XIV et l'Orient";

5 V. J. Puryear, Napoleon and the Dardanelles, Berkeley & Los Angeles 1951,

passim.

6 R. Murphey, "The Ottoman attitude towards the adoption of Western technology",

in J-L Bacque-Grammont & P. Dumont editors, Contributions à l'histoire

economique et sociale de l'Empire ottoman, Louvain 1983, pp.287-298.

7 D. M. Vaughan, Europe and the Turk: a pattern of alliances 1350-1700,

Liverpool 1951, pp. 124, 127.

8 F. M. Gocek, East encounters West: France and the Ottoman Empire in the 18th

century, New York 1987, pp.58, 86.

9 R. Mantran, "Les debuts de la Question d'Orient (1774-1839)", in R. Mantran

editor, Histoire de l'Empire Ottoman, Paris 1989, pp.421-458.

2

2

The setting for this paper is therefore an Empire in gradual decline faced by

increasingly industrialised European powers seeking markets for their products,

willing to use their armies and navies as an arm of commerce, and their military

and naval personnel on missions which included reconnaissances. In what was a

Mediterranean (and, indeed, Europe-wide) game of chess, with ever-moving

alliances, the French Ministry of War attempted to keep up-to-date on Ottoman

military and naval capabilities by studying the strengths and weaknesses of the

Ottoman Empire, by mapping possible invasion routes, and by recording the

reports on defences and weapons composed by officers lent to the Turks. In 1783

and 1784, for example, engineers, artillery officers and sappers arrived in

Turkey, to train troops, found cannon, and build fortifications, within a School

of Military Engineering10. Many such officers were well-educated, and intensely

interested in the antiquities they came across, not only because of a classical

education, but also because such antiquities (roads, forts, cisterns, aqueducts)

might well be needed in the event of invasion, as proved to be the case when

France invaded Algeria in 183011. Since their reports often write at great

length on such matters, and there is no sign of disapproval at what might prima

facie be considered digressions, the Ministry was clearly of the same mind. We

shall examine below some examples of the reports generated during this mission.

For antique remains in western Europe, we can often trace changes to and usage

of ancient monuments century by century, through contemporary accounts12. Such

documentation is very sparse for the Ottoman Empire, and French reconnaissance

reports are therefore valuable today because they are often the only record of

many antiquities since destroyed by pressure of population, or of the more

pristine states of monuments since become dilapidated. Through them we can gain

a much fuller picture both of the “antique landscape” of the Ottoman Empire than

is available from most 18thC or 19thC travel writers or (later) archaeologists,

and of how the Ottomans continued in many instances to use a “military

landscape” bequeathed to them by Rome and Byzantium. To take as an introductory

example the most basic antique feature of all, namely roads: Western Europe was

giving great attention to transport questions in the 18th century, even to the

extent of investigating building roads on the Roman model by excavating and

studying the makeup of stretches of Roman road in France. That such Roman-style

construction was an unattainable ideal because too expensive, is reflected

partly in the recourse to canal-building. But in the Ottoman Empire roads were

especially important, nothing equivalent having replaced what the Romans had

built well over a millennium beforehand. To locate and use such surviving roads

was therefore essential for any army. Their lack was a cause for lament, as in

an 1807 Itinerary from Spalato to Constantinople13: And, what is more, the roads

are such that one might say both that there are none, and that they are

everywhere!

Apart from the general watching interest they had in an Empire which occupied a

substantial proportion of the Mediterranean coastline, three specific factors

throw into relief the attention the French gave to the often venerable

fortifications of the Ottoman Empire. The first was the need to assess the

military strength of the Empire, especially the likely access-routes through the

Dardanelles or the Balkans, or perhaps through Syria; and, given the power of

L. Pingaud, Choiseul-Gouffier, la France en Orient sous Louis XVI, Paris

1877, pp. 95ff; cited in Masson, Histoire du commerce français dans le Levant au

XVIIIe siècle, p.275;

11 M. Greenhalgh, "The new centurions: French reliance on the Roman past during

the conquest of Algeria", War & Society 16.1, May 1998, pp.1-28.

12

M. Greenhalgh, The survival of Roman antiquities in the Middle Ages, London 1989.

13 Génie, Article 14: Turquie, Carton II, 1786-1838.

10

3

Russia, to assess her defensibility from the North and East as well. The second

was the lack of a true fortress-building tradition on the part of the Turks:

rather than build afresh, thereby destroying the fortifications of previous

centuries on the same site, they had often been happy to mend and update Roman

and Byzantine constructions, or to employ Europeans to build fortresses for

them; likewise their frequent use of artillery of monstrous size and hitting

power was mitigated by a tendency not to maintain it well. This leads to the

third factor, namely the employment of French officers to train their troops, as

German officers were used in this century. In the 18th century, the French

sometimes served as adjuncts to the Turkish military, helping with artillery

training, and also with surveys of military installations (although advisors

were withdrawn when Austria declared was on the Ottoman Empire in 1788). These

surveys, of course, also found their way into the archives of the French

Ministry of War. This meant that an observant officer corps, often very

interested in the classics, could travel the country and report back to France

with written reconnaissances.

The Intellectual Background for Reconnaissances: Travel and the Mapping of

France

It is important to bear in mind the scholarly context for such reconnaissances,

which are predicated upon assumptions about military endeavour and horizons

which have since faded. The 18th & 19th centuries regarded scholarship and

treasure-hunting as appropriate activities for their military, blessed by the

ancients. Alexander took scholars with him, to write accounts of his campaigns

as well as to study the art and architecture which their master might wish to

imitate; Napoleon did likewise in Egypt, and started a modest Egyptomania back

in France. The Romans had collected trophies of their conquests; so did the

French. Royal vessels took antiquities from Syria and Libya to ornament the

palace and gardens at Versailles; and much of Britain's antiquarian loot was

conveyed by the Royal Navy. Europe was transfixed by the vision of ancient

Greece, and tended (often unfairly) to see Islam as the ignorant destroyer of

classical remains. The revival of aspects of the classical world, not least

through collecting antiquities, was therefore devoutly to be wished, even if

this meant trying to wipe out successor-states on the same territory. ChoiseuilGouffier, French Ambassador to the Sublime Porte, was more an archaeologist than

a diplomat, and in 1765 actually exhorted Catherine the Great of Russia to

create an hellenic state on the ruins of Turkey, allied to Russia - to rescue

part of classical civilisation, in other words, from what he considered the

tyranny of the Turk14. This idea bore some fruit, since her second grandson of

1779 was baptised Constantine - not far from a deliberate vow to recapture

Constantinople for Christianity and Russia, the more so since talks were held

with Joseph II of Austria in 1780 with this end in view, the annexation of the

Crimea in 1783 and the loss to Russia of some Black Sea forts in 1792 being part

of the process. Choiseul-Gouffier's idea of an hellenic state also came to pass,

albeit on a smaller scale, when the Greek War of Independence (1821-30, with

some Russian intervention) led to the birth of the Greek state on the ruins of

part of the Ottoman Empire, and the destruction of the Ottoman Fleet by

Britain, France and Russia at Navarino in 1827.

For men such as Choiseul-Gouffier, the classical past was much more immediate

than the Middle Ages or Renaissance, and with more impressive monuments. With

P. Masson, Histoire du commerce français dans le Levant au XVIIIe siècle,

Paris 1911, p. 274;

14

4

the development of civilian travel in the 18th century, usually for

architectural or archaeological investigation, or for educating youngsters in

their heritage, the military could join skills with civilians in making highquality reconnaissances. They considered themselves adequately prepared only

when armed with the appropriate ancient authors (whose works, they believed,

could offer important information about strategy, battles and monuments) as well

as the modern travellers who frequently offered commentaries on the ancient

authors as well as on what they actually saw on their travels. Napoleon took

this enthusiasm for the past slightly to extremes on the Expédition de l'Egypte.

Not only was a complete set of copies of dispatches, Orders of the Day, etc kept

so that the history of the campaign could the more easily be written, but books

were sent out to him in Cairo15, amongst them the complete works of Voltaire and

Winckelmann, various military memoires, Gosselin's Géographie des Grecs, and La

Gardette's Ruines de Paestum, presumably because this was the closest

information that could be found to Egyptian architecture. But these were mere

afterthoughts, for Bonaparte took a library of no fewer than 560 works (not

volumes), following a shopping expedition costing over 192,000 livres16. The

works included the Encyclopédie (1,980 livres), the complete Mémoires de

l'Académie des Sciences (1,650l), the Mémoires de l'Académie des Inscriptions et

Belles-Lettres (480l), Choiseuil Gouffier's enormously popular Voyage

Pittoresque de la Grèce, and the Voyages of Captain Cook. The seven parts of the

Choix des costumes des peuples de l'Antiquité might well have offered some

background on Egypt - but could the nine in-folio volumes of the prints of

Piranesi have been for anything other than a kind of pole-star - a comparison

between what the Romans had achieved and what he, Bonaparte, would accomplish?

That such big spending on books bore fruit is evident from the monumental

Description de l'Egypte which is in a manner of speaking France's true monument

to her invasion of Egypt. And the spirit it inculcated is reflected in the works

produced by Bonaparte's officers. Chef d'Escadran Schaouani is a good example,

producing a large quantity of notebooks17 of what he saw in Egypt and further

West, taken during reconnaissances, some with the help of the IngénieursGéographes of the Army. These included not only familiar Egyptian antiquities,

but also Roman forts the measurements of which he gave, probably because he

thought they might be used to house troops for defence. He complains in bad

French of his lack of instruments, interpreter, pencils, pens, or chinese ink,

and the slog of following the marching troops for nine to twelve hours every

day, struck at every step by fresh objects which command one's attention; so the

stops were scarcely times of repose… But then, as we learn from the biographical

notes he gives us18, he was probably well over 50, having started his drawing of

antique ruins in 1746.

Such high-quality preparation evidently became a tradition, surviving the fall

of Napoleon, for he was not the only officer to read the works of the Académie

des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres in Africa. Captain Delambe, writing from

Bone, where he was in charge from January 1833 to November 1839, reported19 on

B6-83: Expedition de l'Egypte: Copies ordonnes par le Premier Consul pour

servir à l'histoire des Campagnes d'Egypte et de Syrie, 1798-1801. Cf chapter I

for the books despatched.

16 6B-80, Toise des depenses faites la le Citoyen Caffarelli, General de brigade

du Genie d'après les ordres du Général en Chef Buonaparte, sur les fonds assurés

par le Ministre de la Guerre, pour l'expedition de la Mediterannee, An 6.

17 B6-79: Mémoires et documents divers sur l'Egypte provenant du Chef d'Escadron

Schouani, 1798.

18 B6-79, Egypte: Notes particuliers et observations de … Schouani.

19 3M541, Dépot de la Guerre: Algérie 1830-1836.

15

5

29 March 1836 to the commanding General on a booklet published by the Academie,

entitled L'Histoire de l'Afrique Septentrionelle. He has read it with interest,

because all his leisure moments have been devoted to this same topic,

discovering the present-day names of Roman sites, the great majority of which he

believed would be a step to recovering their ancient names. Such work has had a

practical outcome, allowing him to correct many errors on the map of Colonel

Lapie - and he has evidently learned Arabic so as to be able to converse with

the locals. Thus we find the instructions20 given to two Ingénieurs-Géographes

who were to accompany M. Michaud to the Orient in 1830. They should learn the

language, read earlier travellers and ancient historians; and since Michaud's

research was the Crusades, they were ordered to undertake sorties designed to

correct the geographical details of central Asia Minor, of Syria and of Arabia

Petraea - regions which, from ancient empire to our own day, have been the

theatre for such important events. But why such solicitude for battles long ago?

Because it was realised that here (just as in Algeria), crusader fortresses and

their predecessors and successors still offered formidable obstacles to modern

armies. Indeed, scholarship could be served at the same time as military

reconnaissance, as is clearly implied by their further instructions: to get to

know, as a matter of the utmost importance, the military positions we should

occupy to defend the country. This would entail what we know of the marches and

military operations of the ancients with the dispositions required today, as

regards the lie of the land, as well as modern tactics and weaponry. In fact,

from the military point of view, this is a thoroughly modern reconnaissance,

using the Crusaders as a convenient skeleton, since their fortifications

perforce obeyed the same strategic laws dictated by the landscape. This same

symbiosis between what the Romans did, and what the French would do in their

footsteps, is a perpetual theme in their conquest of Algeria.

But if Napoleon provided the picture of the complete soldier-scholar, what

formal training was offered for officers to undertake reconnaissances? The only

general instructions that appear to have survived are from 182821, but these

might echo what was expected in the previous century. Reconnaissances should

include a careful note of the types and qualities of building materials to be

found on site, such as stone, wood, metals… Details of what to put on sketchmaps are also given: The houses, stone bridges and all masonry constructions are

to be drawn and coloured red - carte rouge, one might say, for including

antiquities which, in many locations, were the only masonry constructions

existing. Reports should conclude with a chapter of military considerations,

that is, a relation of military events ancient and modern for which the ground

reconnoitred, or its environs, was the theatre. If such events are lacking, one

will note down what is interesting about the history of the country.

What are the sources for such an interest in the antique past on the part of the

military? The impulse goes back to the Renaissance, when ancient military

manuals and tactics were first studied again, but only from texts. By the 18th

century, the desire for detailed knowledge led to systematic excavation and

travel expeditions to parts of the world (such as the Ottoman Empire) that had

not been much visited since the Crusades, except by traders ranged along the

coasts. Indeed, the 18th century saw a developing interest in national history,

including perforce that of the Middle Ages as well as of remote antiquity.

MR1619 Turquie 1619/33: Instruction pour les deux officiers du Corps royal

des Ingénieurs-géographes destinés à accompagner M. Michaud, membre de

l’Académie Française, dans son voyage en Orient, 1830.

21 MR1978/4, Comite Consultatif du Corps Royal: Extrait de l'Instruction pour

l'execution des reconnaissances Militaires don’t les Officiers du Corps Royal

d'Etat Major doivent etre chargés, 1828.

20

6

French scholars, along with English ones, were to the forefront in such

developments; and two large mapping projects bracket our period - the Carte

Générale de la France (1756ff) and the Carte de France (1841). Both undertaken

for census reasons but with an eye to military requirements, they set the scene

for the intellectual horizons of those French officers who write reconnaissances

of the ottoman Empire. It may even be that the vogue for archaeological

knowledge amongst the military may have developed after the production of the

Carte Générale de la France, called the Carte de l'Académie, which was funded by

an Act of Association in 175622. For this project, printed questionnaires were

prepared, asking for names of hamlets, villages, chateaux, rivers, mills, watermills and roads. Respondents were also to be questioned about trees, Piliers de

Justice, crosses, calvaries, gibbets, boundary markers etc etc which by their

height and position servent to indicate in that region the separation of

territories, Intendancies, judicial areas, or Bishoprics - that is, although

many of the items instanced are potentially of antiquarian interest, their only

point in this operation is as boundary markers, for which purposes prominent

antiquities had been used since the Middle Ages. Given that by 1793, a review

showed that by that date some sections of the Carte de France had seen as few as

one impression pulled, most 11 or under, very few 20, and the highest 40, the

Committee of Public Safety determined23 to systematise such works into a General

Depot of all the plans, maps, memoires and works to do with geography,

topography and hydrography considered from all points of view of public utility.

Importantly, this grand plan would include groups of artists charged with mapand plan-making, and divided into five divisions of geography, namely (1)

astronomical, (2) historical and political, (3) physical and economic, (4)

routes by land and communications by sea and (5) military. It is important to

underline the universal thirst for knowledge that such proposals reveal, and

which for our purposes paid dividends in the scholarship and antiquarianism

shown in so many French military memoires and reconnaissances.

Such attitudes were fine-tuned by the time of the 1841 Carte de France which,

like it 18th-century predecessor, was written according to predetermined chapter

headings, including:

- Physical Description;

- Statistics;

- History, including political events and archaeology. Some entries are probably

valuable, because quoting from memoires which may not be printed or published,

or discussing monuments since destroyed or altered24. This project may also

offer some of the earliest accounts of "Gallic" antiquities25.

3M395, Dépôt Général de la Guerre: Carte Générale de France, Rules for

execution by the Engineers, 1757.

23 3M277, Dépôt Général de la Guerre: Comité du Salut Public, Section de la

Guerre, 20 prairial, An 2. For usage of the Carte, cf, loc. Cit. a MS of 25

November 1793.

24 e.g. Captain de Laslases on Chauvigny, in MR1298, pp26-7. Captain Blondat has

several pages on the antiquities in his Mémoire on Poitiers (Carte de France,

1841, carton MR1298, pp.13-16, 25-30). Captain Reverdet’s Mémoire Géodésique

Militaire (Carte de France, 1841, carton MR1298, p.7), notes the high quality

lithographic stone around Chatellerault, with qualities qui sont propres aux

nouvelles applications que l’on fait de l’art lithographique, et qui se prêtent

facilement à la gravure en relief au moyen des acides. - although in this case

not for art, but rather for the growing practice of making multiple copies of

documents, making lithography the predecessor to the photocopier.

22

MR1298/52-59, Carte de France, Feuille de Poitiers, 1842 etc etc. Includes

(as 1298/54) a Plan des Monuments Celtiques de Chateaularcher, dits le Champ de

25

7

As well as the propensity on the part of classically educated officers to read

them for pleasure, reliance on the ancient authors, and on the markers provided

by ruins on the ground and relayed by military reconnaissances, was essential

for any itinerary- or map-making in the Ottoman Empire because the Dépôt de la

Guerre, which held such material in the 18th century, is characteristically

well-supplied with material for Western Europe, especially the borders of

France, but very light on material further East26. Attempts to remedy this

situation were made in 1797 by proposing a library for the Dépôt de la Guerre,

and drawing up very long lists of desiderata, strong on travels and voyages, as

well as on military arts, if somewhat lighter on history27.

Another element in the education of the French military which was a result of

the heady optimism of the Revolutionary period was the foundation of the Ecole

Polytechnique, and its organisation28 to include classes in architecture and

drawing for its students. The students would study architecture, or the

construction, distribution and decoration of private or national edifices. They

would draw from models and from nature, and would familiarise themselves with

the rules of taste in works of composition. Not only that, but a Conservateur du

Cabinet des Modeles was to the appointed - so the students might also study

architecture in the round as well as models of machines.

However, from hints in some of the documents it might be the case that not all

officers had patience with such a historically-based approach to the present.

Toscan de Terrail, on the General Staff in Algeria, prepared 111 pages of Notes

sur l’Afrique29 for his colleagues, and preceded them with an Avertissement

which reveals his frustration with such attitudes: Since one might find that

ther historical section of these notes goes back to too distant a period, deals

with events too well known or with those without a sufficiently direct

connection with the land called "Regency of Algiers", the table hereunder will

offer the reader a method of ignoring everything which might be judged useless…

But this account is purely historical, with nothing at all on the archaeology of

Thorus, Canton de Virome, Département de la Vienne - including views of them,

with three table dolmens (large stone leaning at angle against another), with

galeries, and a plan of a destroyed gallery. Also includes plans of various

important battlefields including Poitiers 732, at 1298/56. Indeed this Carte

(like them all?) includes a large section, Chapitre 5, dedicated to general

History, then Archaeology, then Military History (e.g. 263-74 for Battle of

Poitiers). The author of this account, Le Commandant Saint-Hippolyte, describes

(p. 206) how he had his officers each take account of the celtic monuments in

each section, and describe and mark them; but how the Champ de Thaurus was so

important that he drew it (see above) and described it himself, pp.218-40.

He also notes amphitheatres, walls, aqueducts and Roman roads. Nor is SaintHippolyte the only officer to report on antiquities: 1298/49-51, M. Fourcade,

Feuille de Saumur, Mémoire sur les environs des Trois Moutiers, Vienne, 1841,

includes (at 1298/51) pencil drawings of the Dolmen de Vaon, and a standing

stone “Polven (Caillou de Courcu)”.

Details in 3M249, Catalogue des Mémoires et Manuscrits topographiques et

militaires du Dépôt de la Guerre, An 8.

27 3M267, Dépôt de la Guerre: Bibliothèque; list dated 26 August 1797 (9

fructidor), with a much longer supplement dated Ventose An X.

28 3M311: Ecole Polytechnique, Organisation de l'Ecole Polytechnique, 7 Ventose

An 4.

29 MR881.1, Toscan de Terrail, capitaine d’état major, Notes sur l’Afrique, 111

pages, March 1836.

26

8

the country. Toscan was an exception, as the enthusiasm for reconnaissances

made the Balkans, Bosphorus, Dardanelles, Constantinople and the Greek Islands

will now reveal.

Reconnaissances in the Balkans

It was the task of a Ministry of War to plan invasion strategies even against

allies such as the Ottoman Empire. The difficulty was that that Empire was

visibly collapsing (hence the viability of the Greek War of Independence), and

what would fill the resultant vacuum? Invading the Ottoman Empire through the

Balkans, specifically Croatia30, seemed attractive because the naval ingredient,

and the need for troopships, was much less than that required for attempting the

Dardanelles. General Guillaume assessed the possibilities in the early 19th

century, and set his account31 at the very beginning in its historical context,

giving the ancient history of Nikopolis, Apollonia and the rest - the entrepôt

of the two Empires of Orient and Occident. A powerful reason, he believed, for

taking this route was that in Epirus we could re-establish with very little

difficulty or expense the great roads that the Romans placed there. Guillaume

then parallelled Roman campaigns with contemporary ones, and this description

will include the ancient and the modern geography of this country. There

follows an account of Roman success in Epirus, and the note that the walls of

Actium still stand to ten feet in height, the circus surviving as well. He

completed the circle by drawing contemporary conclusions from Roman campaigns.

Guillaume had been on a mission to Epirus in 1807, when still a Colonel32. This

he accompanied with a map, with the ancient sites marked in red. He compared the

tactics and strategy of Ali Pasha to those that could be found in the Iliad, and

found that nothing is more like the manners of the Greeks in the heroic age, and

like those depicted by Homer, than the manners of the Albanians - not

necessarily a compliment, of course. The conclusion is inevitable: to understand

what is happening now, read up about strategy and tactics in the ancient

authors, for nothing has changed.

We may, however, note that Guillaume's was not the only view of the matter. When

Capitaine du Génie Riollay wrote a memoire in 1810 on north-west Bosnia33, the

planning was done completely without an ancient framework - so presumably taking

the "ancient route" was at least in part a matter of education and personal

predilection.

Or does Guillaume's reconnaissance smell too much of the study rather than the

landscape? It contains no indication that he has actually followed the route he

is recommending; and when, to Riollay's assessment we add that of another

Cf. MR1626/44, dated 15 March 1810: Mémoire sur la Reconnaissance faite dans

la partie Nord-Ouest de la Bosnie, indiquant les routes que pourroit suivre une

armee française qui pénétroit en Turquie en passant de la Croatie.

31 Génie, Article 14: Turquie, Carton 2, 1786-1838: General F. Guillaume,

Mémoire sur la possibilite d'une invasion en Turquie par l'Epire.

32 Génie, Article 14 Turquie, Carton 2, 1786-1838: Rapport de ma mission en

Erzegovine, Albanie et Epire, 1807.

33 Génie, Article 14: Turquie, Carton 2, 1786-1838, Mémoire sur la

reconnaissance faite dans la partie Nord-Ouest de la Bosnie, indiquant les

routes que pourroit suivre une armee Française qui pénétreroit en Turquie

partant de la Croatie, March 1810.

30

9

Engineer Captain, Roux La Mazelière34, writing in 1808, it becomes clear that

Guillaume was indeed unreasonably optimistic and romantic in ignoring the

difficulties. Roux writes from experience: not only are the fortifications along

the route old masonry castles without terrassement, for the most part very badly

maintained, and almost witout guns, but the roads (no hint given of Roman

surfaces) are passable only to pack-horses, there are few stone bridges (hence

impossible to manage with artillery), and the houses are all of wood, so

offering no defensive positions. Bad news though it was, this report was either

highly valued or widely circulated, for the archives carry four copies of it.

The clarity and elegance of these straightforward reconnaissance reports is

admirable, and they are often written by men of culture. For example, General

Danthouard's Mémoire sur la Dalmatie35, dated 10 June 1806, marks antiquities in

the margin: in his two-page account of Zara his catch-heading is a large 70point Musée, with an indication in a private house of a passable collection of

antiquities. Four colossal statues dug up at Nona are to be seen; and of Nona he

notes that it is an ancient town, but which has preserved absolutely nothing of

its splendour under the Romans… At Spalato, on the Dalmatian coast, he notes

that the Venetian extensions to the fortifications of Spalato (with more walls

and bastions outside the Diocletian enceinte) skimped the job, and the

fortifications having been for so long abandoned, have been used as a quarry by

the inhabitants; one section is even called The Breach - that is, they will

steal any material, and not just antiquities. Lassaret, a member of the corps of

Ingénieurs-Geographes, reported on Spalato in 180636, logged earthquake as

responsible for the destruction of antique towns, and remarked that one meets at

every step in Dalmatia the more or less obvious vestiges of Roman towns and

monuments, as well as a large number of coins from the Imperial period. The most

remarkable and the best preserved are those of the town of Salona and the palace

of Diocletian the very walls of which form the first ring of fortifications of

the town of Spalato - i.e. the walls of the palace still in use as such, if not

as any kind of military obstacle, as we saw above.

Reconnaissances and Spolia in the Bosphorus and Dardanelles

Two of Turkey's greatest weapons, and the shield for Constantinople, were the

two easily defensible straits to north and south - the Bosphorus leading to the

Black Sea; and the Dardanelles, the funnel between the Sea of Marmara and the

Aegean, which was Russia's only easy access to the Mediterranean, and the route

for all seaborne trade with Constantinople from further west. Both straits are

so narrow that gunfire from the fortresses which stood sentinel on the European

and Asian coasts could be devastating - hence the frequent descriptions of their

construction and armament37.

Génie, Article 14: Turquie, Carton 2, 1786-1838, Mémoire topographique et

statistique sur la Bosnie, 1 April 1808.

35 21-24/MR1626.

36 MR29-30/1626, Mémoire a joindre a la Reconoissance Militaire de la Dalmatie,

signed “Lassaret Ingénieur et Géographe", December 1806.

37 V. J. Puryear, Napoleon and the Dardanelles, Berkeley & Los Angeles, 1951,

pp.437, with a commented bibliographical note, 421-430. Archives additional to

the Army Archives are available at the Ministere de la Marine (MM,B7, with over

452 cartons); AEMD Turquie (over 65 volumes), and AE Constantinople 74 with

consular material, 1795-1802.

34

10

But what was the quality of the forts and armaments which guarded these straits?

Many of them were antique in origin, or rebuilds using antique materials from

the plentiful antique cities which bordered them; and many of them mounted

cannon still firing marble cannon-balls. We may suspect that the mercantilist

interests of the West, including France, did not run to the installation of

weaponry of European standards (for marble cannon-balls were still being fired

across the Dardanelles in the mid-19th century); but if such antiquities were

sufficient to deter the French from running the straits under war conditions,

the British did indeed do so in 1807 (as a part-result of the Ottoman alliance

with France), and stood off Constantinople38 - the first foreign force to

approach Constantinople since the Cossack raid of 162439.

The Turks made very sure that friendly visitors knew about the power of their

armament, because they provided ceremonial salutes with them, as an English

captain recounts in 1790: The Turks at the Dardanelles always salute with

ball, and the nearer they go to the vessel, the greater the compliment. Each

fort fired seventeen guns; their cannon are monstruous, and the shot flying en

ricochet along the smooth surface of the water across our bows, from Europe and

Asia alternately, and throwing up the sand on the opposite shores, while shouts

of applause from the admiring multitude, hailed us on returning their salute,

crowned this charming morning40. That these cannon-balls were indeed cut from

antique columns (because of their ability to withstand firing, and their

devastating effect when they shattered on the target) is not in doubt. An

English traveller, Dr Hunt, in Turkey probably in 1799, confirms this: In the

great battery are guns of various calibre, and those on a level with the water

are enormous; the bore of them is nearly three feet. We saw a pyramidal pile of

granite shot for these huge cannon, which our Consul told us were cut out of

columns found at Eski Stambol (ancient Constantinople), a name given by the

Turks to Alexandria Troas…41 When he got to Alexandria Troas, he confirmed what

he had been told at Cannakale: Near the ancient port we saw piles of cannon

balls, formed out of granite columns, by order of a late Captain Pasha for the

supply of the forts of the Dardanelles. The voracious appetities for marble of

these cannon is confirmed by their quantity:, M.

Lafitte Clavé, in a long

account of 178442, includes a table of the artillery of the chateaux d'Europe

et d'Asie, reporting 19 ten-feet bronze pieces for the European side, which

fired a 22-inch-diameter stone ball, and one piece 20 feet long, with a 28 inch

diameter, The Asian side mounted 14 22-inch pierriers of ten feet in length.

As for the forts on the Bosphorus, Roumeli Hisar (p.71) has 13 pieces, each 17

feet long, 13 inches internal diameter, which are loaded with stone shot … we

have not been able to determine the weight of these balls since we do not know

the weight of the marble from which they are made compared with that of ordinary

shot. Since Lafitte Clavé was in Constantinople to give lessons on fortification

to the Turks, we can assume that he knew what he was talking about.

A good example of the scholarly bent of some soldiers who reported on the

Dardanelles is provided by M. le Chevalier de Clairac's Mémoire sur les

Dardanelles43 of 1726. Littered throughout with references to classical authors,

V. J. Puryear, Napoleon and the Dardanelles, Berkeley & Los Angeles 1951, pp.

127-147: "That Infernal Strait".

39 Mansel, op. Cit., p.232. The Russians had tried and failed in 1770.

40 Captain D. Sutherland, A tour up the straits from Gibraltar to

Constantinople, London 1790, p.348:

41 Dr. Hunt, Journals, p.84ff., in Rev. Robert Walpole, Memoirs relating to

European and Asiatic Turkey, edited from manuscript journals, London 1817.

42 SHAT MR1616,

Nos 7-8, Reconnaissance de Constantinople, 1784.

43 MR26/1616, begun 2 October 1726.

38

11

cited in Latin in the margin, this account is far different from the typical

Renaissance production, crafted in the study from the ancient authors alone. A

detailed and apparently scrupulous account of some 129 pages, it also has plenty

of references to classical sites, which he actually visited, employing the usual

technique of antiquarians trying to make sense of what the classical authors say

by reference to the topography of what he can see on the ground. He marched, he

tells us, compass in hand, walking at a steady pace, minute-watch and compass in

hand; and whenever we found a well, a fountain, or any larger object, I wrote

its position in minutes and orientation. The chateau vieux d’Asie, according to

what he heard at the Dardanelles and read in Belon, was built by Mahomet II from

blocks taken from the ancient site of Scamandria, half a league from the straits

(Belon p.77). Of the new forts, the one on the European shore mounted

canons-pierriers - guns which threw a marble cannon-ball of between 400 and 800

pounds in weight. This is indeed an observation of concern to the survival of

Antiquity, since the balls were generally carved from antique columns, a

plentiful if diminishing source which was very convenient because little labour

was required to trim shaft-sections to shape, the balls not needing to fit the

barrel tightly44.

Constantinople and Environs

Constantinople, with sophisticated and beautiful multiple defences unbreached

for nearly a millennium, was of particular fascination to classicists and

military alike. In the 18th century, the walls of Constantinople and the

fortresses up the two straits were important military obstacles, and French

accounts offer much interesting archaeological detail not otherwise available.

Thus Major de Lafitte Clavé, writing about 22 April 1784 for the Département

Général de la Guerre et de la Géographie 45, offers a description which forms

part of a larger Mémoire sur la défense du Canal de la Mer Noire. The walls are

very degraded, he writes, with large breaches which have not been repaired.

Indeed, the three enceintes were in the worst possible condition; the walls are

falling down in shreds, as well as the counter-escarpment, and are covered with

creepers and bushes in several places. Neverthess, the author is clearly taking

the walls seriously as a military obstacle remarking, of the section between the

Seven Towers and the sea, that toute all this section of the fortifications was

once upon a time repaired with column shafts and entablature blocks, taken from

antique Greek and Roman buildings which the Turks did not respect; these can be

seen on the facing of the wall (parement), and on several can be read the

remains of Greek inscriptions. This is useful, because it tells us of the

splendour aimed at by the mediaeval reuse of classical spolia. This tranche of

wall does not survive; and we have no accounts of columns used elsewhere in the

walls for repair (i.e. horizontally, as ties). Since this section of wall was by

the sea, we can assume that the columns served here as they did elsewhere in the

Empire as a guard against undertow in the water itself, or at footings level on

dry land as a defence against sapping.

The depradations of canons-pierriers upon antiquities will form the subject

of a future paper. Meanwhile, see the summary in M. Greenhalgh, CISAM DETAILS,

forthcoming.

45 MR1626:

Turquie: pieces doubles 1784-1829; cf. pp.52-60. A draft of this

document bears the exact date.

44

12

Major de Lafitte Clavé also gave an account of a journey southwards from

Constantinople to Bursa, Nicaea and Nicomedia in 178646, which offers equally

valuable accounts of the region. At Bursa, where little remains today of what he

correctly recognised as the Roman walls (The antique sections of these walls are

constructed with great blocks of dressed stone; but they have been re-laid

subsequently with less solidity), he confirms that the defences were in a poor

state; but he also notes that the inner fort, which has completely diappeared,

had towers and a gate decorated to right and left by bas-reliefs which have been

mutilated. We can confirm his good judgment, and his range of interests, by his

admiring comments on the walls of Nicaea, which do survive, built with beautiful

dressed blocks taken from ancient monuments, which attest to the splendour of

this town, and on which several inscriptions may be read. At Nicomedia, where

almost nothing survives today, there were no standing antiquities in his day

either - but everywhere, in the roads and the houses, are to be found fragments

of column, capitals, and other debris which attest that antique splendour which

the Turks have appropriated for their own use.

The archives of the Engineers contain accounts which are not purely military in

intention, but resemble high-quality civilian travel diaries - another

indication of the range of military interests. An example is the late 18thcentury document entitled Instructions pour un Voyageur qui veut voir

Constantinople47, which offers descriptions of the walls (including Greek

inscriptions), and of 13th-century Tekfur Saray (The palace … is remarkable only

for the bizarre nature of some mosaics formed out of bricks laid symmetrically

in the masonry infill between the dressed blocks on the west, and by bronze

frieze ornaments arranged in the window arches, and which make them appea marked

with wavy lines. We know about the diapered walls, which survive: but none of

the bronze ornaments have survived. He records inscriptions in the walls from

the Constantine Palaeologus rebuild, and compares what is left at the Seven

Gates with the Renaissance description of Gillius: he finds only two main

columns flanking the gate, and the bas-reliefs earlier recorded have disappeared

except for one representing a Lioness, the dugs of which are filled with milk,

which is to be found above the Porte, set into masonry work that isd clearly

Turkish. From here he proceeds to S. John Studion, still with its roof on, and

can recall for us the whole structure of the nave, only sections of which

survive: the vault is held up by seven verde antico columns on each side, 6 feet

6 inches in circumference, each of the Corinthian Order, and surmounted by a

frieze of white marble admirably sculpted into foliage. On top of this frieze

are erected seven more smaller columns but well proportioned in relation to

those underneath them. It is impossible to tell their colour, because the Turks

have limewashed them. Next to the church, is a cistern supported on 23 granite

columns.

The Ministry of War also collected when available reconnaissances by foreign

officers. One such is a Russian journal of 182948, conveniently written in

French, the international language of culture. This anonymous officer relates

(correctly) that Mahomet II shot pierriers at the wall in 1453, and he saw the

breach at the Adrianople Gate - still in evidence after over 300 years - by

which he entered the city. He considers the walls very well preserved, except in

some sections covered with the most beautiful creeper, which gives it a

respectably romantic air; and he comments on the coats of arms and Greek

MSS du Génie, 4to/120, Journal d’un voyageur de Constantinople a Brousse

Nicée et Nicomedie en 1786.

47 MSS du Genie, 4to/120, paginated.

48 30/MR1619 Extrait du Journal d’un officier russe, 1829: Notes sur

un voyage

de Constantinople. pp.30-31.

46

13

inscriptions still readable on several towers. But they are outdated: these

defences must have been formidably strong before the invention of gunpowder

[artillery], or when artillery was in its infancy…

Greece and the Islands

The islands of Greece were of continuing importance to the French Navy, offering

convenient ports of call and occasionally bases for their ships, whose task it

was to protect and where necessary defend French commercial interests in the

whole of the Levant. The Navy was in a better position than the Army to assess

harbours and anchorages; and, in this capacity, they frequently came across

activities involved in the transport of antiquities from Turkey and Greece back

to Europe, although usually only the debris of the crime. The British competed

with the French for commercial advantage, and used the Royal Navy in the same

fashion. Thus Captain D. Sutherland visited Paros, and recalled its reputation

for marble: While its marble quarries were being worked, Paros was one of the

most flourishing of the Cyclades; but on the decline of the Eastern Empire, they

were entirely neglected, and are now converted into caves, in which the

shepherds shelter their flocks … Several fine blocks of marble – fragments of

columns, are lying close to the water’s edge, and seem to have been brought

there by travellers, who for want of a proper purchase to get them on board,

have not been able to carry them farther…49

Just what a general reconnaissance involved for the French in the late 18th

century is illustrated by that ordered by the Marechal de Castries, Ministre de

la Marine, in 1784. The Engineer Lafitte Clavé was on loan to the Turks, and

offer the Porte the important service of reconnoitering her frontiers50. The

survey seems to be a broad one, being entitled Mémoire Militaire sur les

positions relatives des Isles et des Côtes de l’Archipel du Levant, and is

inscribed To serve as an introduction to the General reconnaissance ordered by

the Maréchal de Castries 1784. How latitudinarian de Castres’ General

Reconnaissance was understood to be can be seen from Lt-General Durnan's 251page folio reconnaissance of Crete51, which includes no fewer than seven pages

on a a detailed description of a visit to the Labyrinth, complete with balls of

twine and torches. The promised plan of the site is unfortunately missing, but

they encounter and transcribe some of the graffiti of earlier travellers. This

whole account should be most useful to historians of 18th and 19th century Crete.

Frequently, such reconnaissances tell of antiquities completely lost or

substantially altered, usually because of the pressures of population and hence

need for building materials, of which antiquities were often conveniently placed

near the shores. The islands were easier to rob than the mainland, with most

antique remains on or near a working harbour or anchorage. The same block and

tackle used for shipping supplies could be used for antique statues or columns both considerably easier to ship than a mast, for example. Thus an Italian

report on Ithaca, of 180752 identified the fortress of Ulysses and, in the

locality called Polis are antique walls, where it is said there once existed an

A tour up the straits from Gibraltar to Constantinople, London 1790. Pp.14950.

50 MR3/1626, p.36.

51 MR 6/1616.

52 MR1628/48 Rapport sur l’Ile d’Ethiaki (Ithaque), (in Italian, in spite of its

title), 1807. Perhaps written by or for L’Amministratore d’Ithaca, Felichs

Zambelli, whom it mentions.

49

14

ancient city. Also in the locality called Santi Tanassi are to be discerned

traces of an antique temple. These discoveries were made only a few years ago by

two English travellers, who spent several days on the island - this account

perhaps written by or for L’Amministratore d’Ithaca, Felichs Zambelli.

Zante is another island on which antiquities are today scarce. L.Fauchier

reported53 in 1808 the few remains he found: The only antiquities surviving on

this island are those found at the village of Melinadro, six miles from Zante.

There is a well-preserved Greek inscription in the church of Saint Dimitry on a

stone slab in use as the altar table [and he transcribes and translates it].

Paolo Mercati had seen more a couple of decades previously, for he enumerates54

several, including the tomb of Cicero [!] which he draws; and which he says was

found in 1544 by Fra Angelo Gugliese Minor near to the catholic church of Santa

Maria delle Grazie, whilst digging within the Monastery - together with two

glass phials, one for tears, the other for ashes, which he also draws. Mercati

was more assiduous than the Frenchman who followed him for, trascribing the same

inscription Fauchier remarked upon, he goes on to describe how in the same

village are to be seen a variety of antique columns and several disks [cut from

columns] of cipollino. It is therefore not unlikely that these remains were part

of some antique temple. He mentions other column pieces in the church of San

Giovanni in the village of Bujato - another antique temple! Also near to the old

Castle above Zante is a brick pavement, from which he deduces a temple of Venus

or Apollo.

The Temple at Bassae, in the Peloponnesus, with its 38 Doric columns, was

described in a reconnaissance in May 182955. The anonymous author correctly

describes the pronaos, with ten ionic columns, or rather half-columns. From

another undated (but late 18th century?) reconnaissance56, we learn not only

about the remaining walls of Phigalea, but also about Bassae. At Pavlitsa (the

site of Phigalea), we find all around the village, and especially to the East

where still stand the remains of a gate and walls well preserved in fine white

blocks … and the enormous ring of fortifications of the ancient Phigalea. The

inhabitants of Pavlitza say there are no fewer than twenty-four towers.

(Apparently he didn’t go to look for himself). Nearby, to the West, antique

columns have been incorporated into a church, in which are column shafts of

about 50 centimetres in diameter, an upturned white marble column of about 80

centimetres, and two others with doric capitals. The same happens in another

church to the North-East, at Ennlisia Tis Panagias, where on the ground itself

can be seen the remains of an enclosure paved in marble tiles. In the walls of

the church, the thickness of which is that of the fortifications, are columns of

a smaller diameter which seem to have formed the peristyle - suggesting a temple

turned directly into a church. But close-by was a much more important monument,

named Bassae or, by the locals, I Styli - the Columns. In the author's correct

estimate, this is the most beautiful and the best preserved of the ancient

monuments of the Morea. He describes its situation, confirms that as in his

later colleague's day, 35 columns were still standing, and marvels that there

are 15 columns to right and left on which the architrave still rests with no

cracks and no missing sections … In spite of the debris cluttering the sacred

area the various parts of the temple are easily distinguishable.

MR1628/49, L. Fauchier, Rapport sur l’Isle de Zante, 2 January 1808, p. 27.

MR1628/57, Paolo Mercati, Descrizione dell’Isola del Zante, undated, but

perhaps late 18th century.

55 MR 88/1628, Itinéraire de la route de Navarin à Nauplie par Arcadia,

SiderCastro, Suano, Tripolitza, les Moulis, May 1829, pp. 16-17.

56 MR1628/88 fols 13-16.

53

54

15

The French interest in Greece and the Islands, whilst part of a commercial

context as we have seen, also partake of a growing passion for things Greek

(rather than Roman), which had begun in the late 18th century. This provoked an

unseemly but fruitful rush for Greek antiquities on the part of the German

states, the British and the French - in the last case leading to the acquisition

of two famous trophies, namely the Venus from the island of Melos (1820), and

eventually the Winged Victory from the island of Samothrace (1863).

Reconnaissances further East

French reconnaissances were also made away from the “European” invasion routes

in order to be prepared in the case of invasion of Turkey from Russia. Once

again, these are often rich in archaeological observations. Hence a Plan de la

Ville et de la Citadelle de Kars (Arménie), dated 2 December 1853, attached to

the MS Mémoire sur l’Etat actuel de l’Armée d’Anatolie by C. A. de Challaye,

consul de France (in Istanbul) - and dated 25th December 185357. This contains a

long description of the citadel and of the fortifications of Erzeroum, and still

expresses amazement at the construction: the enceinte is built from stones of

great size, and perfectly assembled with lime and sand, and the revetment built

out of dressed stone, jointed with much care and precision. Of Kars’ citadel,

the author remarks that the external rings of fortification having been built a

considerable time before the period of Vauban, these works cannot resist attacks

by modern Science or the military techniques which she teaches. He makes a

similar point about Erzerum: a strong site, with hills above it - though doesn’t

state, but rather implies, that the reach of modern artillery renders the

citadel easy to destroy.

In an early 19th-century reconnaissance beginning in Syria, from Aleppo to

Eviran58, the anonymous author visits Edessa (Urfa), describes the fortress as

in ruins (as it still is), and then the city walls, which have disappeared: The

fortress itself, as well as the walls of the city, are beginning to fall down in

various places. Greek, Latin, Armenian and oriental inscriptions are to be seen,

and mosaic paintings {des peintures en mosaique] - and says the fortress was

built by King Abagar. The same document notes of the city of Diyarbakir (p.14)

that This town, a theatre of war for several centuries, still retains several

vestiges of her ancient monuments. Greek and Latin inscriptions are to be seen

on her gates, and mosaic paintings and bas-reliefs are to be found within

churches and in other places.

On many occasions, we could wish for much longer descriptions. When Fabvier &

Lamy journeyed from Constantinople to Teheran at the beginning of the 19th

century, their account59 took in the walls of Nicaea, which survive (and

although ruined could still put up a good resistance to attack. They are adorned

by a large number of towers of beautiful construction). But all Ankara's walls

except for the Citadel have now gone, so more than the following would have been

useful, especially since the authors seem able to distinguish the various

building periods with accuracy: three sets of fortifications are to be seen,

flanked by square towers. The first is modern, and built from debris parts of

which once belonged to beautiful examples of Roman architecture. The second and

MR1620, Turquie 1811-1840; pp.47ff for Erzerum, pp.81ff for Kars.

MR1625, Description de la Route d’Alep à Eviran. No name, no date, but the

Dépôt Général de la Guerre stamp in red bears a crowned eagle.

58 MR1673: Perse, MM Fabvier & Lamy, Route de Constantinople a Thairam

[Teheran], undated but early 19thc: see pp.6 & 22.

57

58

16

the third are older, protecting the upper parts of the town, reducing there to a

single wall which crowns the top of the hill.

In March 1800 M. Tromelin made a reconnaissance60 right across Anatolia from

South to North, beginning in Cyprus and finishing in Constantinople. It is

interesting because of the large quantities of antiquities he records. He

visited Phaselis (naturally by boat - there were no roads), then called Porto

Gennesse because the Genoese once had a trading post there. At Cnidus are still

to be seen the remains of an ancient mole, only very recently destroyed, and at

Bodrum, he believed he had found a Temple of Venus & Mercury on the right of the

port. At Mylasa he recorded the Temple of Augustus (in Pocock's day a very fine

temple survived complete) and then visits the mausoleum-like tomb, and the

temple at Euromos. Proceeding across country toward Mount Latmos, he comes

across Alinda which, like everyone else, he misidentifies as Alabanda (which is

further to the East). I discerned a large quantity of ruins, of large buildings

clothed in dressed stones of some three or four feet in length, two in breadth

and six in depth. The Aga has established himself in a square court, closed

within by walls, a little above and some fifty paces from the ruins of a great

building. The building the Aga used on the ancient agora has now completely

disappeared, but the "large building" is the magnificent market hall, still

standing but with its floors missing. Tromelin calls this "the palace", and

describes the uses to which its remains were put: The palace and the porticoes

decorated with oval columns have been destroyed. The locals tell me that an

earthquake toppled these monuments a few years ago. But I found their columnstumps in the Aga's courtyard, chiselled out to make mangers for his horses … I

also visited several of the tombs described by Pococke, which still survive. One

of them had stone seats inside, and both cornice and basement storey: I went

inside, which is now divided into two compartments in use as stables. The palace

half-way up the hill is of grey granite just like the tombs, and is used to

shelter the village's camels. The consoles on which the columns of this palace

rested are still to be seen - square, and about one-and-a-half feet per side

[i.e. supports for the floors]. Reusing tombs is common everywhere; at Alinda it

was especially appropriate since the walls of the city are on the side of the

mountain, and some at least of the monumental tombs are on the site of the

present village61, on gently sloping ground between the ancient city and the

plain. (It should be underlined that two-storey tombs of the "mausoleum" type

found at Mylasa make excellent houses, with the people above, and the beasts on

the ground floor.)

Having crossed the Maeander, going north, Tromelin finds he is travelling on an

ancient road across a marsh (that is, the flood-plain of the river), made from

marble slabs, and repaired with antique column-shafts. This is too far north to

be the Sacred Way to Didyma (which he does not visit), and is presumably north

of Priene: we headed northwards and came upon a narrow road-surface of some four

feet in width, dressed with large stones which for the most part were of white

marble. I frequently remarked column shafts several of which were cannellated.

This road is about a league in length, and crosses an immense marsh, with a lot

of standing water. Hence in many places arches have been built under the road to

allow the water to flow beneath it. This whole project seems to me mediaeval,

and too much of an undertaking to have been made by the Turks. Nevertheless,

there is nothing in the construction of the arches to suggest they might be

antique; on the contrary, the stone blocks, parts of column-shafts, and bits of

marble capitals from which they are built prove that the ruins of ancient

39/1617 Untitled account of a voyage from Cyprus to Constantinople by M.

Tromelin, pp.33.

61 G. Bean, Turkey beyond the Maeander, London 1971, fig 52 for an illustration.

60

17

buildings were used in their construction. This road is sinking by the day and,

given the very little care lavished upon it, will soon be totally unviable. Not

only have antiquities been used to repair the road: they are also in heavy use

in Turkish cemeteries. About a mile from Guzzel-Kissana the marsh ends, and

gardens begin, as well as a Turkish cemetery at the entrance to the village, and

all the stones that the Muslims are in the habit of putting at head and foot of

their graves are all column-shafts of white marble; many are cannellated, and

are probably about two feet in diameter and some fourteen or fifteen feet high,

others considerably less. I saw several Corinthian capitals, and beautifully

worked frieze and architrave blocks.

This was not the only reconnaissance Tromelin made, for in autumn 1807 he went

through Northern Greece, and to Thessaloniki62. Crossing the Vale of Tempe,

north of Larissa, he came across the remains of an antique road in one of the

clumps of plane trees characteristic of the region, which followed the side of a

gorge, and with its full width excavated from the rock, and paved with the

marble extracted from the cutting. This ancient road might be some twenty or

twenty-five feet in breadth. It is paved with large slabs of marble, and

everywhere in a good state of conservation - and it develops into an ancient

road still viable for modern artillery.

Reconnaissance at War: Algeria 1830-1845

Roman roads are very common in Algeria; their cities, fortresses and fortified

waystations, and above all roads are found at every step. Every col, every

strategic position is provided with a station consisting of a square fort

constructed from strong dressed stone blocks … From our observations it is clear

that the Romans built three parallel strategic routes, leading inland from the

sea…63

In Algeria, which the French had invaded, easily overthrowing Turkish rule

represented by the Bey, and were trying to pacify and colonise, Roman remains

were especially important, because they offered a lifeline to an army short of

money, supplies, men and backup. Reusing Roman forts saved shipping building

materials from France; Roman silos provided storage for grain, and Roman

aquedeucts and cisterns offered water. Roads were particularly important,

because of the need to move artillery around - so Roman roads were frequently

repaired, as a much cheaper and quicker alternative to new construction.

Reconnaissances in Algeria generally follow a set pattern of ruled columns

containing a listing of salient features, and sketches where necessary. One

example can stand for all: a anonymous itinerary of 184264. It gives stages on

the left-hand page, with sketches of rivers, defences, villages where need be;

and notes on specifics and on the road, on the right-hand opening. Some of the

sketches are detailed enough to be useful, such as the ruins at Doueira, the

blockhaus at Belidah, and Belidah itself, this last described as guere en effet

qu’un poche d’anciennes constructions. We are also given a sketch of the

aqueduct of Medeah, with its two tiers of arches, and the Ruins of a Roman camp,

the lines of its fortifications being drawn on the ground by lines of great

Génie, Article 14, Turquie: Carton2, 1786-1838, J. J. Tromelin, Officier

d'Etat Major, Voyage en Turquie, written up 10 February 1808.

63 11-13/1315, Lieutenant Montaudon, Memoire sur l’Algerie, 1844, p.30.

64 63-4/1314 Itinéraire de la route d’Alger à Boghar, dated 1842; cf. Fols 24v,

38v, 70v and 88v-89 for references.

62

18

dressed blocks near to Bervnaguiah – an irregular rectangle 160 metres broad by

250 metres long.

M. Dureau de la Malle, writing about the antiquities of Algeria in the Journal

des Débats in 1836, suggested65 that his gathering together of ancient and

modern accounts could be helpful in the coming push to occupy Constantine.

Statesmen and soldiers would profit from reading the topographical discussions

which he gave in abridged form. He also stated his belief that a member of the

Academie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres should accompany the army, to draw

the important ruins, city fortifications, and inscriptions.

To the extent that antiquarian expertise was needed to establish a viable map of

Algeria, and that scholars needed the support of the army in their endeavours

for safety and transport, there was a symbiotic relationship between the

military and the archaeologists in Algeria - the more so since so many soldiers

had antiquarian interests. Proof of the crucial need for reconnaissances and

archaeology to join together in order to supplement inaedquate modern maps of

Algeria comes from a member of the Scientific Commission on Algeria. E.

Pellissier, writing in 184366, noted that Already in the current situation

archaeology, everywhere we have been able to reach, is coming to the aid of

geography. Indeed, the Arabs leave things to go to ruin much more than they

actively destroy, so that the ruins of ancient monuments remain standing, and

every dig near them bears fruit. But, in this desolate landscape, ruins

frequently cover earlier ruins. In the level above ancient geography lies, so to

speak, Saracen geography, whioch has its own obscurities. How many cities still

standing in the times of Leo Africanus or of Marmol, have now completely

disappeared, so that their location is almost as difficult to find as that of

Scylax' Carthaginian cities? The author’s technique was to compare what he saw

on the ground, and then use the ancient authors - Strabo, Ptolemy, and the

mediaeval copy of an ancient map called the Tabula Peutingeriana. His concern

was to identify cities from antiquity, as a way of setting up his notional route

maps. Remarking briefly on the great number of ruins on the road from

Constantine to Setif, he noted that first making a large-secale map, and then a

simple comparison between this map and the Tabula Peutingeriana will suffice to

give them [the ruins] the appropriate names. Before we laugh at the use of a

mediaeval copy of an ancient map as a method of checking modern mapmaking, and

suspect (wrongly) that the French did not value accuracy in mapmaking, it is as

well to assess the problems the French faced in Russia and in Egypt, for both of

which countries modern maps were nearly non-existant. In 1812, the French began

not only the invasion of Russia, but the preparation of a map of Russia, in at

least 121 sheets. For Egypt, they prepared a map of 47 sheets, including

letterpress for 8011 italic words and 13,694 capital and roman words!67

Confirmation that reconnaissances including notices of antiquities were

considered useful as opposed to simply academic comes from the French engagement

in Algeria, when knowledge of surviving antiquities became essential to their

safety, signalling, food storage and water supply. In Algeria, the French were

treading in the footsteps of the Romans, and what their predecessors had

Génie 8.1 Constantine, Carton 1, 1836-1840, M. Dureau de la Malle, Notice

topographique et historique sur les villes de Constantine et de Guelma, from the

Journal des Débats, 27 & 31 December 1836.

66 MR1314: Algérie,

E. Pellissier, Mémoire sur la Géographie ancienne de

l’Algérie, 7 August 1843, 121 pages, written at Sousse.

67 3M262: Dépôt Général de la Guerre, Impression et Gravure, Comptabilite, 18e

siècle An XII-1814.

65

19

accomplished was used as a guide for strategy in war and colonisation, as well

as an invidious comparison with which to taunt those commanders whose actions

were not consonant with Roman actions and achievements. Chef de Génie Devay,

writing from Mascara on 11 April 1844, provides a considered review of what the

French were doing in Algeria, based on his reconaissance68 of the Habra, to the

West of Algiers. He begins: Since it is necessary at this stage of our African

domination to try and face all those grand questions which have to do with the

future development of this country, let us therefore come to grips with that

which will prove that we are indeed attached to the soil of this country, and

that we wish to base its prosperity on solid foundations independent of all

considerations external to Algeria. Here, as in all those places where projects

and useful thoughts inspire us we can find the example of previous dominations.

The first, whose traces are still written on the land, the greatest, the most

instructive of all, the Roman occupation has left here, in the valley of Ouedel-Hammam, incontestable traces of its passage in the shape of a complete city

- a city still standing in order, so to speak, to attest to the ancient

prosperity of this region. He went on to discuss the cost of erecting a dam to

re-fructify the country around (and such a dam was indeed built). He also found

canals and dikes, which leave no doubt at all that these works are antique, and

that it is possible to put them back in working order with the least possible

expense - since so many parts survive in good condition. He concluded by noting

that such work would help colonisation here, and we will then set ourselves at

last on the practical, rational and methodical path which would have assured the

Romans indefinite posession of these lands of Africa and Barbary … We shall tie

one by one the various knots of this colonising network which the political

science of the Romans thought necessary to tie up her conquest and fortify her

domination of the country.

In 1832, on 7 July, General Boyer wrote to the Minister of War recounting a

sailing expedition to the east of Algeria, with explorations on land by his AdC,

Captain Tatareau, who found at Saguid BeySultan some very remarkable structures

… several coupled capitals, crumbling vaults, column shafts, and a wall