Solving Varnish Problems at Power Generation Facilities

advertisement

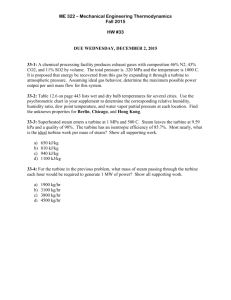

Solving Varnish Problems at Power Generation Facilities Greg J. Livingstone, Clarus Technologies Advancements in gas turbines have made them the technology-of-choice for new power generation projects for the past two decades. The advancements, however, place higher demands on turbine oils. Elevated operating pressures and temperatures, advancements in seal technology, preventing oil leakage, and smaller reservoir sizes have created new lubrication challenges and problems. One Northeast power producer experienced some major problems with varnish formation in its turbine oil. Plugging and sticking of an electrohydraulic pilot valve, a critical component in its combustion turbine, was affecting the turbine’s performance. Through an effective oil analysis program along with an onsite fluid processing service utilizing electrostatic oil cleaners, the power producer was able to eliminate its varnish problem. Background One of the growing lubricant problems with combustion turbines is varnish accumulation originating from thermal and oxidative oil degradation. Some potential negative effects of varnish in turbine systems include: Reliability problems with control valves, Performance problems with heat exchangers, Premature filter and strainer plugging, Advanced wear rates on bearings and valves, Reduced heat transfer, resulting in the lubricant’s inability to cool bearings because the varnish acts like an insulator, and Catalytic effects on the deterioration of the turbine oil. The bottom line is: varnish build-up can significantly increase maintenance costs and may result in unplanned outages. Peak-load combustion turbines are typically operated in a cyclical fashion, and as such, are among the most severe turbine oil applications. The fluids are subjected to high temperatures during operation and are then cooled down during stand-down periods. This heating and cooling cycle subjects the oil to extreme thermal and oxidative conditions. Although varnish can be caused from a wide range of sources, most varnish problems in turbine oils are a result of thermal and oxidative degradation. Both processes involve free-radical chain proliferation. Thermal degradation occurs without the presence of oxygen and is usually caused by hot spots in the system or micro-dieseling due to entrained air bubbles. Oxidative degradation occurs with oxygen acting in conjunction with elevated temperatures and catalysts, such as water and metal particles. It is not possible to monitor thermal and oxidative degradation on the molecular level, but it is possible to observe the products formed, such as acids and sludge-like insoluble suspension, occurring at the termination of the degradation mechanisms. Under the right stressing conditions and upon the depletion of anti-oxidant additives, both oxidative and thermal degradation can happen simultaneously and continuously in lubricants. Regardless of the degradation mechanism, high molecular weight insoluble oxides can form. These oxides can then precipitate out of the fluid to form sludge and varnish. Analytical Detection: Varnish Marker Series Fluids in steam and gas turbines are significantly less tolerant of varnish formation than lubricants in most other applications. Generally, the initiation of a performance problem can occur long before analytical results from routine oil analysis indicate a problem. Therefore, supplemental tests are required to identify the presence of insoluble oxidation by-products, the root-cause of varnish. The following series of tests, called the Varnish Marker Series, were created by Clarus Technologies to detect insoluble oxidation by-products: colorimetric analysis gravimetric patch test RULER® Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) These tests are designed to identify varnish potential before routine analysis, thereby providing turbine users with an additional proactive maintenance tool. Group I vs. Group II Basestocks Solvency, or a fluid’s ability to dissolve another substance and create a homogeneous mixture, is related to the level of soluble oxides that oil can hold before precipitation occurs and varnish is formed. Group II basestocks have a higher viscosity index and fewer impurities than Group I basestocks (solvent-refined), and provide a higher resistance to oxidation and formation of oxidation by-products. Once oxidation by-products form, however, their highly polar nature is less stable (soluble) to Group II basestocks and is more prone to lay down on dipolar metallic surfaces. This may also be due to soluble oxidation by-products that become insoluble at an earlier stage in Group II basestocks than in Group I. Case Study: Incorporating Electrostatic Oil Cleaners in Onsite Fluid Processing Background of the Problem and the Solution A peaking power plant in the Northwest had varnish formation in its GE Frame 7EA industrial gas turbine. The electrohydraulic pilot valve, a critical component of the control mechanism, was plugging and sticking on a regular basis. Physical inspection of the failed valves revealed a brown, sticky coating. The same brown deposits were also noticed on other turbine components and in the bottom of the main lube oil reservoir. The turbine’s main lube oil reservoir is filtered through high capture-efficiency three-micron filters maintaining a low particle count. Routine analytical results of the fluid showed no abnormal levels. The turbine fluid was an ISO VG 32 Group II basestock. Its aniline point was higher than the Group I basestock turbine oil’s aniline point, indicating lower solvency (Table 1). Click here to see Tables 1 and 2. The following steps were taken to remove the varnish precursors from the turbine fluid: 1. All turbine oil was emptied out of the reservoir. 2. The main lube oil reservoir was cleaned by confined-space tank cleaning. 3. The turbine oil was filtered back into the reservoir through a high-density sieve absorption filter and an electrostatic oil cleaner. 4. Several electrostatic oil cleaners were set up in a kidney loop on the reservoir providing slip- stream filtration for 30 days. Analytical Interpretation: Root Cause Analysis Before and after samples, as well as samples taken at intervals during the 30 day project were analyzed. The results are shown in Table 2. Based on the analytical results, it was determined that varnish formation was due primarily to oxidation. Following are results from the Varnish Marker Series: Colorimetric Analysis The before sample produced a patch with a strong brown hue (Figure 4), which indicated that oxidation by-products were present. The varnish tendencies chart (Figure 1) based on colorimetric analysis was developed in-house after analyzing dozens of samples of various turbine oils. The difference in solvency between Group I and Group II basestocks accounts for the greater lay-down rate tendency of insoluble oxidation by-products in Group II. This chart was developed as a guideline for the varnish potential of turbine oils and is to be used in conjunction with other analytical tests. Figure 1. Colorimetric Analysis FTIR Analysis There was a slightly elevated peak (1714 cm-1) in the carbonyl region (Figure 2), which indicated the presence of oxidation by-products. FTIR analysis often can indicate the presence of oxidation byproducts before acid number (AN) runs up because it is measuring several oxidation by-products including keytones, esters, carboxylic acids, carbonates, aldehydes, anhydrides and amines. In addition, there was no evidence of nitration (1630 cm-1) in the FTIR scan. Nitration can be a sign of thermal degradation (as opposed to oxidative degradation) due to hot spots or the effects of microdieseling, a phenomenon caused by excessive air bubbles in the fluid. Figure 2. FTIR Analysis of Carbonyl Region Gravimetric Analysis Gravimetric analysis measures the total amount of insolubles in a product greater than 0.3 microns. Although the used sample had a relatively low measurement of 0.8 mg/100ml, it was higher than would be expected when compared to the turbine oil’s ISO particle count of 14/12/9 (Figure 3). This signified a high presence of insolubles under 2 microns, which is consistent with oxidation byproducts. Figure 3. Contamination Trend Analytical Results: Removal of Varnish Precursors The analytical results indicated that the electrostatic oil cleaners were successful in removing the varnish precursors from the fluid. Several factors point to this conclusion: The colorimetric test indicated a substantial reduction in yellow and red values (Figure 1). FTIR analysis indicated a reduction in the carbonyl region (Figure 2). The gravimetric analysis indicated a reduction in insolubles (Figure 3). There was a visible difference between the patch of the before sample and a patch of the after sample (Figures 4 and 5). The color of the turbine oil was considerably lighter at the conclusion of the job. Figure 4. Colorimetric Patch - Before Sample Figure 5. Colorimetric Patch - After Sample The rotating pressure vessel oxidation test (RPVOT) results indicated that the fluid’s resistance to oxidation improved (Table 2). The 78 percent improvement in RPVOT can be attributed to the removal of oxidation by-products making the fluid’s antioxidants more effective. If all the fluid’s antioxidants had been depleted, no measurable increase in RPVOT would be anticipated. Physical Inspection and Follow-up Analytical Work Six months after the job’s completion, a physical inspection of the electrohydraulic valves was conducted. No visible signs of varnish existed on the valves. In addition, there have been no performance problems with the electrohydraulic control valves. Oil analysis revealed virtually identical results as those taken the day the job was completed. It is important to note that this power plant has had limited operational hours during this six-month interval. Therefore, another inspection is planned at the anniversary of the job. Removal of Oxidation By-Products from Metallic Surfaces The electrostatic oil cleaners not only removed varnish pre-cursors from the turbine oil, but also removed oxidation by-products from the system’s internal surfaces. The analytical results indicate that the fluid became slightly more contaminated after 10 days of processing compared to the end of the job. This can be attributed to stripping of the oxidation by-products from the metallic surfaces before they were removed by the electrostatic oil cleaners. Physical inspections of system components at the conclusion of the job confirmed this theory. (Note: Eradicating insolubles from metallic surfaces are complex and beyond the scope of this case study. Refer to Sasaki, A., et al, “Mechanism of Adsorption and Desorption of Oil Oxidation Products on and from Metal Surfaces” Kleentek, Japan.) Inadequacies of Dumping and Recharging Studies show that varnish on surfaces cannot be removed by dumping and recharging the system with new fluid. Not only will the varnish remain within the system, but the varnish may act as a catalyst to oxidize a new fluid charge. Typically, the time period before varnish becomes a performance problem in a turbine system is halved with each dump and new product recharge. (Note: Additional information on this subject can also be found in Sasaki’s paper on “Mechanism of Adsorption and Desorption of Oil Oxidation Products on and from Metal Surfaces”.) This user solved its electrohydraulic valve plugging and sticking problems by employing an onsite fluid processing service utilizing electrostatic oil cleaners. This service allowed the customer to better measure the project’s success while avoiding capital expenses. In addition, the service provided confined space tank cleaning, removing accrued contamination from the bottom of the reservoir. It is possible to achieve similar results by using electrostatic oil cleaners full time on a reservoir as the primary source of insoluble contamination control. In summary, the case study uncovered several findings. First, it reaffirmed the belief that varnish is a growing problem in the power generation industry, and turbine applications are less tolerable to varnish build-up than most other lubricant applications. Next, the case study showed that varnish detection is not normally achieved through traditional routine oil analysis testing. Incorporation of colorimetric analysis, FTIR, gravimetric analysis and the RULER® can assist in determining root cause analysis and indicate a fluid’s potential to produce varnish. It was also shown that electrostatic oil cleaners are capable of removing varnish precursors from oil. They have a positive impact on the fluid’s resistance to oxidation provided antioxidants remain in the oil. In addition, electrostatic oil cleaners are capable of removing insoluble oxidation by-products from a system’s internal surfaces. Finally, the power generator was able to eliminate its valve problems by using electrostatic oil cleaners through an onsite fluid processing service. System inspection six months later indicated excellence performance. References: 1. Yamaguchi, T. (2001, June). Investigation of Oil Contamination by Colorimetric Analysis. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. STLE/ASM Tribology Conference Proceedings. Society of Tribologists and Lubrication Engineers. Toms, A. and Powell J. (1997, August). Molecular Analysis of Lubricants by FTIR Spectrometry. P/PM Technology. Herguth, W. and Warne, T. (2001). Turbine Lubrication in the 21st Century. West Conshohocken, Pa: ASTM International. Fitch, J. (2002, January-February). Demystifying Sludge and Varnish. Machinery Lubrication, pp. 2-4. Fitch, J. (1999, May-June). Using Oil Analysis to Control Varnish and Sludge. Practicing Oil Analysis, pp.25-33. Young and Robertson (1989). Turbine Oil Monitoring. West Conshohocken, Pa: ASTM International. Reyes-Gavilan, J.L. and Odorisio, P. (2002). A Review of the Mechanism of Action of 8. 9. 10. 11. Antioxidants, Metal Deactivators, and Corrosion Inhibitors. Basil, Switzerland: Ciba Specialty Chemicals. Sasaki, A. (1987). The Use of Electrostatic Liquid Cleaning for Contamination Control of Hydraulic Oil. STLE 42nd Annual Meeting Proceedings. Society of Tribologists and Lubrication Engineers. Sasaki, A. (2002). Mechanism of Adsorption and Desorption of Oil Oxidation Products on and from Metal Surfaces. Tokyo: Kleentek Industrial. Smith, A. (1986). Aspects of Lubricant Oxidation. West Conshohocken, Pa: ASTM International. Fitch, J. and Troyer, D. (2001). Oil Analysis Basics. Tulsa, Okla: Noria. RULER® is a registered trademark of Fluitec International.