Five Bridges along students` pathways to college

advertisement

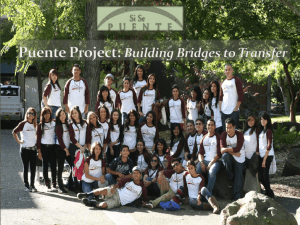

AUTHOR'S NOTE: This article draws from research supported by grants to C. R. Cooper, J. F. Jackson, and M. Azmitia from the University of California Linguistic Minority Research Institute; to C. R. Cooper and B. Thorne from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Pathways Through Middle Childhood; and to M. Azmitia and C. R. Cooper from the Center for Research on Education, Diversity, and Excellence of the U.S. Office of Education. I thank colleagues Margarita Azmitia, Robert G. Cooper, Cynthia Garcia Coll, Jacquelyne F. Jackson, Edward M. Lopez, Nora Dunbar, Jill Denner, Ron Gallimore, Patricia Gandara, Bud Mehan, and Barbara Rogoff, as well as the students, families, and outreach program leadership, including Ben Tucker, Liz Chavez, Yvette Gullatt, Elizabeth Dominguez, Carrol Moran, and Edward Aguilar. The comments of Patricia Gandara, Courtney Cazden, and two anonymous reviewers greatly improved this article. Please direct correspondence to C. R. Cooper, Department of Psychology, Social Sciences 2, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, ccooper@cats.ucsc.edu. Five Bridges Along Students' Pathways to College: A Developmental Blueprint of Families, Teachers, Counselors,) Mentors, and Peers in the Puente Project CATHERINE R. COOPER What program components might enhance our effectiveness in promoting college access for all students? This article considers five bridges along students' pathways to college: family involvement, culturally enriched teaching, counseling, mentoring, and peers. Longitudinal case studies of Puente students highlight how these bridges function along Latino students' pathways to their college and career aspirations. Bridges often extended beyond high school to support students' college enrollment, transfer and retention. A developmental model and prototype database are proposed for both qualitative case studies and variable-based analyses of bridges across students' worlds, family demographics, college and career aspirations, math and English pathways, and college admission and enrollment. Developmental models and longitudinal research can help outreach programs such as Puente strengthen bridges along multiple pathways to college and careers. As these tools advance science, policy, and practices, they can also transform academic pipelines. STUDENTS' PROGRESS from early childhood to college, career, and family roles has been compared to a ball rolling through an academic pipeline. There are three important differences between this tidy image and reality. Unlike a ball that remains unchanged as it moves through the pipe, students change along their pathways through childhood and adolescence to adulthood. Unlike a ball's direct route, students' developmental pathways look more like those of explorers navigating through unmapped worlds of families, peers, schools, and communities. As they pursue their dreams for school, career, and other goals, youth meet barriers that may divert or even stop their progress. Finally, unlike a sturdy pipe, programs that bridge across gaps or barriers along students' pathways are themselves changing and even fragile, as they respond to funding pressures, gains, and losses as well as shifting political sands. This article considers how to strengthen programs by mapping how their components may function as interconnecting bridges along students' pathways to college and careers. College outreach programs such as the Puente Project, AVID (Advancement Via Individual Determination), EAOP (Early Academic Outreach Program), MESA (Mathematics, Engineering, Science Achievement), Upward Bound, I Have a Dream, and GEAR UP (Gaining Early Awareness and Readiness for Undergraduate Programs) have taken on key roles in strengthening diversity in higher education (Hayward, Brandes, Kirst, & Mazzeo, 1997; Mehan, Hubbard, Villanueva, & Lintz, 1996). These range from competitive programs, whose graduates typically attend universities, to selective programs, whose graduates go on to either 4-year or community colleges, from which they may transfer to 4-year institutions. Of course, based on the U.S. Civil Rights Act of 1964 (U.S. Department of Education, 1988), which forbids discrimination on the basis of "race, color, or national origin," public schools are in principle inclusive programs that offer equal access to collegeprep classes. Continuing lawsuits against school districts attest to the limits of this democratic ideal. An inclusive program approach can be seen in the college awareness activities of GEAR UP, in which entire schools are funded in partnerships with community organizations. Systematic analysis of the implementation and impact of these rapidly proliferating programs is a growing concern for educational scholars, policy makers, and practitioners (Gandara & Bial, 2000; Perna & Swail, 2001). To increase the numbers of Chicano/Latino students who become eligible for the University of California and go on to 4-year colleges, Felix Galaviz and Patricia McGrath designed the High School Puente project by building on the Puente community college model. The program draws students across a range of skill levels in what can be considered a selective approach. Puente targets five core components: high school teachers providing intensive college-prep English classes on Latino literature in 9th and 10th grades, bicultural counselors guiding students toward college through high school, Latino community professionals providing mentoring, families being involved with students' pathways to college, and peer networks of Puente students who support each other's college goals (Gandara & Bial, 2000). This article highlights how these components can work as bridges along students' pathways to college. These bridges are illustrated with cases of high school Puente students who were followed from the time they entered the Puente program in ninth grade through high school graduation and college enrollment. Finally, the article considers how developmental models and research tools can link case studies of individual students' pathways to group patterns and how using such developmental tools can help scholars, policymakers, and educators link programs through the pipeline, thereby enhancing students' access to higher education. FIVE BRIDGES ALONG PATHWAYS TO COLLEGE: FAMILIES, TEACHERS, COUNSELORS, MENTORS, AND PEERS Research suggests that five bridges are at work in the Puente Project: families' involvement, teachers' intensive instruction, guidance counseling, mentoring, and support of college-bound peers. These play complementary roles in supporting pathways to college. Some of these component bridges are common in programs and some are rare, but we all have more to learn about each bridge and how it can complement others along students' pathways to college. Students' challenges and resources across their families, peers, schools, and communities affect their program participation, college eligibility, enrollment, and progress as well as program effectiveness (Cooper, 2001). We are beginning to learn that one way programs work is by helping boost the resources and buffer the challenges students find in each of their worlds as they bring college and career dreams and aspirations into realities. The following cases are adapted from those developed by Gandara (in press), who focused on an intensive sample of 27 students studied over 4 years. These students had similar demographic backgrounds, with most of their parents being immigrants from Mexico with modest levels of formal education, and families speaking only Spanish or both Spanish and English at home. Students ranged across four categories of achievement and motivation. The highest achievers began high school with a grade point average (GPA) of 3.5 and aspired to attend 4-year colleges and universities, yet most showed significant declines in both their grades and aspirations, with their families and peers both resources and challenges. Notably, they all maintained close relations with other Puente students, studying together and supporting each other. The moderately high achievers began high school with GPAs of 3.0 but graduated with 2.82, so they focused their college plans on state universities or private 4-year colleges rather than the more competitive University of California campuses. Again, it was striking that more successful students chose their friends from among Puente participants. The lower-achieving students began high school with less well-developed skills and modest goals. Their GPAs averaged 2.5 and dropped to 2.0, but they graduated planning to attend community college and transfer to 4-year schools. No students in this group chose Puente students as close friends. And the lowest achieving students began high school with 1.67 GPAs, all wanting to go to college, but they did not spend time with other Puente students nor did they maintain contact with Puente teachers or counselors, although those who stayed in school did improve their grades. This article draws from Gandara's analyses of these 27 students to illustrate how the five bridges may function-or falter-across achievement levels. Families Promoting "The Good Moral Path" From Childhood to Adulthood Family involvement is one of the most widely discussed and touted program bridges, although its nature and the extent of implementation can vary (see Tierney, 2002, [this issue]). Latino parents, primarily Mexican immigrants, have described their children as nearing the crossroads between the good moral path–el buen camino-and the bad path-el mal camino (Azmitia & Brown, in press; Reese, Balzano, Gallimore, & Goldenberg, 1995). These parents considered moral guidance their primary role and sought to protect children from negative peer influences. To these parents, strong moral upbringing included and supported school achievement. Parents held high aspirations for their children to become doctors, lawyers, or teachers. With a school-based sample, one study interviewed Mexican immigrant parents (Azmitia, Cooper, Garcia, & Dunbar, 1996; Cooper et al., 1994). Most worked as farm laborers or in canneries and had left school in their Mexican villages in childhood, so by fifth grade, children exceeded their parents' schooling, making it difficult for parents to help with homework. Others understood the importance of college but did not know about application procedures or financial aid. But parents helped by making homework a priority over chores and holding up their own lives of physical labor as examples of what not to do. In many Latino families, older siblings taught reading, math, and school expectations to younger brothers and sisters, and university students convinced parents to allow younger siblings, especially sisters, to join them at college (Cooper, Jackson, Azmitia, Lopez, & Dunbar, 1995). This sense of responsibility to family can be both a resource and challenge to students. In this example from Gandara's case studies, a student drew inspiration from her family yet also drew upon Puente teachers and counselors to build a bridge from family responsibilities to her new life at college, so she could sustain her dream, and that of her father, for a college education: Raquel gave Puente credit for helping her with writing, teaching her about the importance of her GPA and giving her information about college. When Raquel immigrated to the U.S., she was in fourth grade. Her parents lacked a formal education and came to this country so their children could get one. She named her father as the person she admired most because he worked so hard to give his family a better life, and she felt a debt for his sacrifices. Her sister earned her teacher credential and supported Raquel's schooling. Raquel began high school with a 2.6 GPA, wanting to go to college but also needing to learn English. Her GPA dropped to 2. 1, but she still hoped to go to the University of California. Raquel did not spend time with other Puente students, although her friends said they wanted to go to college. Despite problems with science classes, Raquel took geometry in summer school to get back on track to calculus and raise her grades. When Raquel graduated from high school she chose to attend the local state university, but she worried about studying with many distractions at home, so her Puente counselor helped her set study times at the library. She was doing well and pursuing a degree in business administration. Teachers and Counselors: Enrichment and Bridging From Families to College Teachers-from any ethnic background-can serve as cultural brokers when they give students experiences talking and writing about their dreams for careers, education, families, and their communities. Puente's culturally enriched English classes are central to the program's mission to make school not only relevant but a safe place for students to develop their sense of cultural identity (see articles by Cazden, 2002, and Pradl, 2002, in this issue). Bicultural counselors also act as bridges when they help youth succeed in school and achieve their dreams. Some review assessments of English language learners to ensure they are not misplaced in special education. Of course, teachers and counselors can also act as institutional gatekeepers when they assess students against standardized benchmarks that determine eligibility for college-prep, vocational, or remedial classes and for programs such as Puente (Erickson & Schultz, 1982), or discourage them from taking advanced English, math, and science classes required for university admission and attempt to enroll them in vocational tracks. In the following case from Gandara's analysis, the student drew inspiration from Puente teachers and counselors, whose help was needed beyond the high school years. Many people argue that the highest achieving students do not need support to make it to college, and program resources should be spent on more deserving and more vulnerable or at-risk students. Still, students' complicated personal lives and responsibilities and financial challenges can make pathways to college uncertain, so the continuing intervention of Puente program counseling beyond high school remain a key resource. When family members are unfamiliar with the U.S. educational system, the program appears to be a crucial bridge from high school into college in students' lives. Andres finished ninth grade with all As and dreamed of a career in law enforcement and joining the FBI. He lived with his stepfather and mother and helped his mother deliver newspapers early each morning. Although Andres spoke positively about his biological father, tensions eroded their relationship. Andres supported his Puente friends by tutoring them and encouraging them to take AP and Honors classes. He too took college-prep classes and graduated with 3.74 GPA and 11 20 SAT scores. His counselor and teachers helped him apply to a nearby prestigious 4-year college, but his concerns about money and helping his family led him to join the Marine Corps Reserves to help pay for college and defer college. He attended community college, joined its Puente program, and maintained a 3.5 GPA, with plans to graduate from the local state university. Mentors: A View of the Future Community mentors from a range of ethnic backgrounds can act as culture brokers when they help students gain educational experiences and acquire bicultural skills for success in school (Cooper, Denner, & Lopez, 1999). Many share a common language and even a family history with Students and pass on their understanding of how to retain community traditions while succeeding in school and college. Like Latino parents, staff often define success in life in moral terms as well as by school success. Researchers have found that the benefits of mentoring on academic outcomes are mediated partly through improving parental relationships (Rhodes, Grossman, & Resche, 2000). In a large study of 959 youth from ages 10 to 16 in Big Brothers/Big Sisters programs, randomly assigned to treatment or control and questioned at program entry and 18 months later, mentoring led to reduced unexcused absences and enhanced perceived scholastic competence (with no effects on self-worth, school value, and grades). However, studies of mentoring suggest some students prefer mentors closer to them in age (Gandara et al., 1998; Mejorado, 1999; Public/Private Ventures, 1996). Mejorado (1999) found that mentors helped by accepting how youth defined success, by tutoring, teaching time management and how to choose friends, talking about the future, and going on field trips. They provided support and challenges when grades slipped. Mejorado found that the strength of mentors' relationships with students predicted their English and math grades and university eligibility. The mentoring component appears, like family involvement, to be one of the weaker bridges in the program, with implementation a continuing challenge across program sites (see Gandara, 2002 [this issue]). Still, we hear in Gandara's (in press) case studies that career mentoring may offer even the most vulnerable students a sense of future and purpose for staying in school, whether or not they continue to college: Carlos, one of the lowest achieving students as he entered high school, credited mentoring from Puente for his caring about college and learning how to prepare for careers. Carlos was determined to do better than his brothers. He started high school with low grades, with a 1.5 GPA in ninth grade and improved to 3.5, although he slipped to 2.92 as he began cutting classes. He chose friends outside of Puente who pressured him to cut school. After a fight at school, he was asked to leave the program, but Carlos ultimately graduated from another high school. Peers: Both Crucial Resources and Continuing Challenges Peers can make the worlds of school and outreach programs appealing. Students of all ages see peers as key sources of emotional and practical support for going to college, but they may also find it difficult to maintain ties to their neighborhood friends who do not understand their college dreams and accuse them of pretentiousness and disloyalty (Cooper et al., 1995). In the following case, Gandara found evidence that peers-both friends and a boyfriend-may be a key factor in what makes the Puente program work, yet they may also create continuing complexities in navigating the path to college. Ofelia, one of the highest achieving students, credited her Puente peer study group and her boyfriend with her academic comeback. Ofelia came to the U.S. when she was seven. She began high school with a 3.8 GPA and hoped to become a doctor, lawyer, or CEO. To help pay for college, though, she wanted to join the military or go to the Naval Academy. Her parents separated when she was young, so she spent most of her childhood with foster families. Her mother had an elementary education and difficulty maintaining stable home and work life. Since her mother was incarcerated on drug-related charges, Ofelia had to augment the family income and lived with her older brother and then later with her boyfriend's family. Taking on several jobs to help support herself took a toll on Ofelia's health and grades, which fluctuated from a high of 3.7 to failing all her courses. She took night classes and summer school to make up for failed courses and raise her GPA, She studied often with Puente friends and volunteered at the local hospital and library. She graduated with a 2.4 GPA and 900 SAT, and she enrolled in a state university with financial aid. Although Puente staff encouraged her to stay, eventually she returned home, where she and her boyfriend enrolled in the local junior college. A DEVELOPMENTAL BLUEPRINT: HOW YOUTH IDENTITIES AND "GOOD BURDENS" LINK GENERATIONS AND BRIDGE ACROSS WORLDS These cases show the intricate and sometimes daunting challenges youth face as they forge their college and career identities while trying to coordinate the expectations of their families with those of peers, schools, and communities. Programs such as Puente can boost resources that youth draw from each world and can bridge across these worlds to build pathways to college, career, and family roles (Cooper, 1999). Sometimes the same experiences can be-paradoxically-both challenges and motivating resources or "good burdens." For example, in one study, Mexican-descent sixth-graders applying for a selective program described their dreams of becoming doctors, lawyers, nurses, and teachers, as well as secretaries, police officers, firefighters, and mechanics, although many of their parents worked as agricultural fieldworkers or held service jobs (Cooper et al., 1999). Studies of outreach programs report how program leaders can spark students' goals to do something good for their people by taking jobs that would help their community, such as becoming politicians, counselors, or helping build low-income housing, even if these were lower-paying jobs (Cooper et al., 1995). As one outreach program student said, "Money is important, but it is not the issue. We have the burden-and it's a good burden-of helping our people." For these reasons, youth and their families often benefit from emotional and instrumental support of programs that offer them bridges across their worlds as they move through elementary, middle, and high school to college and college-based careers. Devoting resources to understanding these bridges-both their strengths and, especially, when they fail-can illuminate the realities that shape or undermine college eligibility, admission, and retention (Edgert & Taylor, 1992; Latino Eligibility Task Force, 1993). Cultural research partnerships link generations and bridge across worlds as they focus on students' pathways to college. They reach across lines of race, ethnicity, socioeconomic class, and gender to work with youth, families, schools, and programs. These partnerships draw both on qualitative methods, such as interviews, field observations, and case studies, and quantitative methods (including surveys, grades, test scores, and statistical analyses). One partnership involved more than 500 youth, primarily Latino, participating in a selective program that awarded scholarships to sixth-grade students from low-income families and offered activities to help students stay on track to college. With the program director, researchers created a longitudinal database of youth records, including application essays, grades, and responses to annual surveys and activities (Dominguez, Cooper, Chavira, Mena, Lopez, Dunbar, & Denner, 200 1). Another partnership involved more than 200 youth in the University of California Early Academic Outreach Program. Working with program directors, researchers traced links from career and college dreams and challenges and resources from families, teachers, programs, and peers as predictors of high school grades and, later, college eligibility and enrollment (Cooper, Cooper, Azmitia, Chavira, & Gullatt, 2002). Each of these research partnerships drew on a developmental model known as the Bridging Multiple Worlds Model to create a database tapping five key dimensions: • • • • demographics of students' families and communities through the academic pipeline; students' career and college goals and identities over time; students' English and math academic pathways to college eligibility, enrollment, graduation, and careers; students' challenges and resources, including enriched teaching, counseling, tutoring, mentoring, family involvement, and peers; and • programs and partnerships at local, regional, state, and national levels. For example, the demographics of programs are key windows on their inclusiveness. As part of enforcing civil rights laws, the U.S. Office of Civil Rights helps schools and programs to monitor demographic indicators of student diversity (U.S. Department of Education, 1988). Who is eligible? targeted? selected? Who participates, who is missing, and who drops out? Mapping family demographic background-by ethnicity, immigration history, home language, parent education and literacy, urban/suburban/rural residence, age, and gender of program participants compared to their schools, districts, some who seem on track can suddenly become derailed. Most Puente students, even at this point, were still vulnerable to pressures that could undermine their ambitions. Their intense concerns about school and unresolved issues with parents reflected a need for both academic and emotional support during and beyond their last year of high school. These case studies suggest that even the highest achieving students were challenged, so the Puente Program could not be seen as "creaming" students who did not need the program's support. The cases also suggest challenges and vulnerabilities for the coming years in these students' lives, as hinted by many leaving for college tentative about their decisions and feeling homesick and isolated. SUSTAINING RESEARCH PARTNERSHIPS AND ALLIANCES Programs, students and families, K- 18 faculty and administrators, legislators, and education writers are partners in keeping the academic pipeline open to diverse students. Yet programs have proliferated with little studentlevel longitudinal analysis of who participates over time, what program elements help which students, and how programs and partnerships develop over time as learning communities. Ironically, many program events are underused while underrepresentation of low-income, urban, rural, and ethnic minorities continues. Meanwhile, media coverage of outreach programs creates hopes of simple one-component or "silver bullet" solutions or relies on single meetings or press conferences rather than thoughtful, ongoing dialogue. Helping partners develop a common language to adapt best practices for local communities, states, and nations strengthens diversity throughout school systems across democracies, whether they be states or nations. Teams of youth and families work as researchers with outreach program staff in formative evaluation to develop longitudinal case studies of student pathways to college (Cooper, 1999). Partnerships ask who is selected, who participates, and who is missing in programs. What are the daily realities of students' lives with their families, peers, schools, and communities that help or hinder participation decisions and college eligibility, competitiveness, and enrollment? Tracing different routes to college, directly from high school and through community colleges, benefits local and system-level stakeholders, including program directors, regional coordinators, frontline staff, and students. In the partnerships, youth can work as researchers with frontline staff to survey demographic portraits; career and college identities, challenges, and resources across worlds; and math and language pathways of classes and grades. Youth and staff can compile and graph students' responses and work with program directors and staff to graph worlds and pathways in programs as part of formative evaluation (Dominguez et al., 2001). Our common goal for programs such as Puente is to link them with schools, families, and other community-based organizations to enhance and sustain access to college for children and youth of diverse ethnic, racial, economic, and geographic communities. Communities' capacity to be "where diversity works" rests on customizing local programs while staying attuned to common goals and collaborating among partners-students, families, schools, community organizations, legislators, businesses, and media. Achieving these goals is enhanced with clear conceptual models of change, testing and comparing them with evidence, and strengthening communication among stakeholders with an ongoing three-step cycle: a) developing models of continuity and change, with accompanying data templates; b) testing these models with longitudinal case studies and quantitative statistics on students, programs, and partnerships across regions by linking local descriptions to quantitative measures of change; and c) building and sustaining alliances of program directors; K-18 faculty and administrators; students and families; legislators; business leaders; and education writers, with public access to proceedings. Key to this effort is that teams of researchers, practitioners, and policymakers, are contributing to models of what local, community-specific, and common program elements enhance program effectiveness. Parallel flow charts can trace how many students flow through programs beginning with selection, orientation, or other "first contact" events (Smith, 1985). Research on local communities addresses questions such as: Which students are wage earners for families so cannot attend after-school, Saturday, or summer programs? Which parents rely on radio, television, or word of mouth rather than print because of their modest literacy in English and native languages? What policies and practices can be scaled up and which must be local? To expand and weather funding cuts, programs can share materials and staff, sponsor joint activities, and develop complementary services. Such alliances and cycles of research, policy, and practice have begun. In describing one alliance for research on diversity and equity, Oakes (2001) identified six factors she considers essential for diverse students' successful pathways to college: college-going culture of beliefs and values, wherein adults and peers see college going as expected and attainable and the required effort and persistence as normal; • rigorous academic curriculum with college-prep, honors or advanced placement courses; • high-quality teaching by qualified teachers that engages students in work of high intellectual quality and opportunities to learn; • intensive academic and college-going support with tutoring, SAT preparation, coaching about college admissions, and financial aid; • multicultural, college-going identity, so students develop confidence and skills to negotiate college without sacrificing their identities and connections with their home communities through bridging their multiple worlds; and • parent and community connections for college-going and academics, where parents learn about curriculum, teaching, college preparation, and college going, with access to college-savvy social networks. (p. 2) In their analysis of outreach programs across the United States, Gandara and Bial (2001) note that programs such as Puente target individual students and their families, screen through selection, and group select students into classes at school. Puente could partner with alliances as well as more inclusive programs to transform schools and help retain the highest risk youth. Dosage effects, despite high attrition rates, indicate that more time in programs predicts greater benefits, so Puente might also link to programs that begin earlier in the pipeline. Inevitably, most programs serve only some students and miss others and create discontinuity in services, and their impact erodes when they end. We observed students migrating across programs during elementary, middle, and high school as well as community college; professionals might observe these students' pathways for ideas on bridging across programs. Program partnerships can also build across staff leadership, and Puente could partner with inclusive programs. The modest reported gains in GPA or test scores suggest programs may start late (most in high school) and not operate sufficiently long, intensively, or extensively. Puente might start earlier and increase dosage of events over time. Although most programs are not linked across K- 12 and higher education, such partnerships can be assets. Longitudinal data, including that linking high school to community college, will help outreach programs conduct cost-benefit and comparative benefit analyses. As we look to the future, we have much to learn about individual bridges and their interconnections. Close relationships with caring and knowledgeable adults who monitor students appear key, but research on mentoring has just begun to answer basic questions. The same is true for peer relationships of students navigating pathways to college. The role of students' cultural and family traditions in college-going identities is another weakly understood yet crucial process that could be monitored more closely, especially as students become more diverse in cultural traditions. Although monitoring and guidance happen through teachers, counselors, mentors, and special classes, programs such as Puente may also benefit from joining Web-based career counseling projects. Although it is understandable that most programs, including Puente, cannot provide scholarships, the case studies starkly illustrate that financial aid counseling-if not scholarships-is another crucial bridge for low-income students. Finally, the policies of precollege outreach program design and funding often refer to abstract and generic concepts of families, schools, peers, and communities, but just as real bridges must fit their local landscapes and flex with the heat and cold of the seasons, so too must enduring programs find ways to engage with the real and shifting contours of students' lives in their particular families, schools, peers, and communities over time. We have much to learn about the physics and the engineering of bridges along students' pathways to college. REFERENCES Azmitia, M., & Cooper, C. R. (2001). Good or bad? Peers and academic pathways of Latino and European American youth in schools and community programs. Journal for the Education of Students Placed at Risk, 6, 45-7 1. Azmitia, M., Cooper, C. R., Garcia, E. E., & Dunbar, N. (1996). The ecology of family guidance in low-income Mexican-American and European-American families. Social Development, 5, 1-23. Cazden, C. B. (2002). A descriptive study of six High School Puente classrooms. Educational Policy, 16, 496-52 1. Cooper, C. R. (1999). When diversity works: Formative evaluation of student outreach, UC System-regional partnerships, and student pathways through college. Santa Cruz: University of California Office of the President Outreach Evaluation Advisory Committee. Cooper, C. R. (200 1). Bridging multiple worlds: Inclusive, selective, and competitive programs, Latino youth, and pathways to college. Affirmative development of ethnic minority students. The CEIC Review: A Catalyst for Merging Research, Policy, and Practice, 9, 14-15, 22. Cooper, C. R., Azmitia, M., Garcia, E. E., Ittel, A., Lopez, E. M., Rivera, L., et al. (1994). Shifting aspirations of low-income Mexican American and European American parents. In F. A. Villaruel & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Environments for socialization and learning: New directions in child development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Cooper, C. R., Cooper, R. G., Azmitia, M., Chavira, G., & Gullatt, Y. (2002). Bridging multiple worlds: How African American and Latino youth in academic outreach programs navigate math pathways to college. Applied Developmental Science, 6, 73-87. Cooper, C. R., Jackson, J. F., Azmitia, M., Lopez, E., & Dunbar, N. (1995). Bridging students' multiple worlds: African American and Latino youth in academic outreach programs. In R. F. Macias & R. G. Garcia Ramos (Eds.), Changing schools for changing students: An anthology of research on language minorities (pp. 211-234). Santa Barbara: University of California Linguistic Minority Research Institute. Davenport, E. C., Davison, M. L., Kuang, H., Ding, S., Kim, S., & Kwak, N. (1998). High school mathematics course-taking by gender and ethnicity. American Educational Research Journal, 35, 497-514. Dominguez, E., Cooper, C. R., Chavira, G., Mena, D., Lopez, E. M., Dunbar, N., et al. (2001). It's all about choices/Se trata de todas Ins decisiones: Activities to build identity path ways to college and careers. Retrieved online at http://www.bridgingworlds.org Edgert, P., & Taylor, J. W. (1992). Final report on the effectiveness of intersegmental student preparation programs: The third report to the Legislature in response to Item 6420-0011-001 of the 1988-89 Budget Act. Sacramento: California Postsecondary Education Commission. Erickson, R., & Shultz, J. (1982). The counselor as gatekeeper: Social interaction in interviews. New York: Academic Press. Gandara, P. (2002). A study of High School Puente: What we have learned about preparing Latino youth for postsecondary education. Educational Policy, 16, 474-495. Gandara, P. (in press). The Puente Program. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Gandara, P., & Bial, D. (200 1). Paving the way to higher education: K- 12 Intervention programs for underrepresented youth. Washington, DC: National Postsecondary Education Cooperative. Gandara, P., Larson, K., Mehan, H., & Rumberger, R. (1998). Capturing Latino students in the academic pipeline (Report No. 1). Sacramento, CA: Chicano/Latino Policy Project. Hayward, G. C., Brandes, B. G., Kirst, M. W., & Mazzeo, C. (1997). Higher education outreach programs: A synthesis of evaluations. Berkeley: Policy Analysis for California Education (PACE). Latino Eligibility Task Force. (1993). Latino student eligibility and participation in the University of California: Report number two of the Latino Eligibility Task Force. Santa Cruz: University of California. Mehan, H., Hubbard, L., Villanueva, I., & Lintz, A. (1996). Constructing school success: The consequences of placing underachieving students in high track classes. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Oakes, J. (2001). Research to make a difference. Los Angeles: University of California at Los Angeles. Perna, L. W., & Swail, W. S. (200 1). Pre-college outreach and early intervention. Thought and Action: The NEA Higher Education Journal, 27, 99-110. Pradl, G. M. (2002). Linking instructional intervention and professional development: Using the ideas behind Puente high school English to inform educational policy. Educational Policy, 16, 522-546. Public/Private Ventures. (1996). Mentoring: A synthesis of P/PV's research: 1988-1995. Philadelphia: Author. Reese, L., Balzano, S., Gallimore, R., & Goldenberg, C. ( 1995). The concept of educacion: Latino family values and American schooling. International Journal of Educational Research, 23, 57-81. Rhodes, J. E., Grossman, J. B., & Resche, N. L. (2000). Agents of change: Pathways through which mentoring relationships influence adolescents' academic adjustment. Child Development, 71, 1662-1671. Smith, M. P. (1985). Early identification and support: The University of California-Berkeley's MESA Program. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. College-School Collaboration: Appraising the Major Approaches, 24, 19-25. U.S. Department of Education. (1988). Education and Title VP Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination based on race, color or national origin in programs or activities which receive federal financial assistance. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights.