1 How are markets organized? Draft version. Comments welcome

advertisement

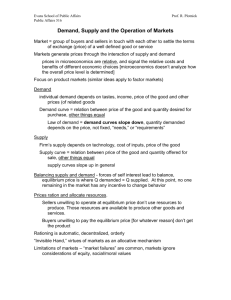

1 How are markets organized? Draft version. Comments welcome. Göran Ahrne, Patrik Aspers and Nils Brunsson May 2011 Theories about markets stand in a complicated relation to theories about organization. Some economic theories state that the opposite of the market is hierarchy. But the opposite of hierarchy is not market but rather voluntariness; hierarchy means that someone else decides what is to be done while voluntariness means that the actor himself makes the decisions, something that occurs in many other contexts than on markets. It sometimes seems as if by hierarchy is meant organization. It is a confusing usage: organization is an institution in which one element may be hierarchy but which also contains a number of other elements. We hold that it is more fruitful to compare market to organization than to hierarchy. Market and organization constitute different institutions. That does not mean that they are opposites or irreconcilable. In this paper we shall argue that they can be combined and that they are nearly always combined in practice. We argue that markets are nearly always organized, even though the degree and kind of organization may differ. The fact that hat markets are organized has important consequences for how they function and for how we can understand and analyze them. 1. Market or organization? Economists tend to see markets as naturally generated. They stress that markets appear and function well when ”economic men” meet to satisfy their preferences by trading goods and services. Neither economic men, preferences, commodities, nor the institutions making commerce possible are explained – they are instead exogenously given in relation to the market. The market is described as a natural consequence of 2 people’s mutual adjustment to each other (Lindblom 2001). Nobody needs to tell market actors what to do, or tell them to start acting; they are, so to speak, born with these capacities. As the market actors signal their preferences through prices, there will be a balance in each market between supply and demand. A market equilibrium has been established as a consequence of mutual adjustment (Hayek 1973; Hayek 1988; Smith 1981). Because this process is considered a ”natural” or ”spontaneous” consequence, there is no need to explain markets according to many economists; the existence of the market is rather the starting point for further analysis. Oliver Williamson, for instance, argued, ”In the beginning there were markets” (1975:20). Organization is, at most, something that can replace the market when the price equilibrium fails, ”organizations are the means of achieving the benefits of collective action in situations in which the price system fails” (Arrow 1974:33.) Sociologists are more divided on the question of whether markets are spontaneously arisen or actively administered. Some sociologists have emphasized how markets are the result of mutual adjustments (Luhmann 1982; Luhmann 1988; Smith 2007; White 1981; White 2002a; White 20089. Most sociologists argue, however, that markets are actively administered. Several use the terms organization and organizing to describe this administration. The most prominent idea is seeing states as central to the formation of markets, (Fliegstein 2001; Fliegstein and Mara-Dritta 1996.) Already Polanyi meant that markets are organized by a central administration: ” Where markets were most developed, as under the mercantile system, they throve under the control of centralized administration… Regulation and markets, in effect, grew up together” (1957:71.) Fliegstein argues that organization of markets should be considered a political process (Fliegstein 2001), and his focus was on strategies and ”conceptions of control”. But the active administration does not have to be through a state. Abolafia stressed the importance of markets being constructed, not least in the study of market makers. He argued that: ”The social constructivist perspective suggests that markets are not spontaneously generated by the exchange activity of buyers and sellers. Rather, skilled actors produce institutional arrangements: the rules, roles, and relationships that make market exchange possible” (Abolafia 1996:9.) According to Abolafia, these market 3 makers see themselves as the creators of the market. They organize the market by upholding rules and standardising commerce. Callon emphasises that ”the market implies an organization, so that one has to talk of an organized market (and the possible multiplicity of forms of organization) in order to take into account the variety of calculative agencies and their distribution!”(Callon 1998b: 3.) Donald MacKenzie, influenced by Callon, has made several thorough studies of how markets have been organized, e.g. markets for emission allowances (MacKenzie 2009.) These have been created by political decisions with more or less support from market actors. Furthermore, he has shown that organizing by organizations has been a central part of the organizing of markets. By maintaining that markets are actively administered sociologists criticise the economic approach. They often use the concept of organization as a term for this active administration. But what is meant more exactly by organization is often unclear and several questions are left unanswered: which elements on markets are organized and which are not, and not least, how does the organization happen? This goes also for the literature in political economy that describes how unions have influenced markets directly and through the state (e.g. Hall and Soskice 2001; Korpi 1983), but focus has not been on how this has been brought about. The latter literature has often taken over the view of what a market is from economists and as we have seen, this means that the question of organization tends to disappear. What is missing from today’s literature on this subject is a systematic discussion of how organization and market are connected. One might say that economists have taken the market for granted. Sociologists have touched upon organization but have not succeeded in explaining what it means. We shall describe the connection between organization and market and how markets are organized. We shall take as our point of departure a fairly precise concept of organization that is both more comprehensive and narrower than those current. We shall start by defining the concepts of market and organization. In section 3 we shall show that it is possible to achieve well functioning markets on the basis of complete, formal organizations and in section 4 is shown how markets also can be partially 4 organized. In the 5th section we describe the consequences of organization, not least for the stability and changeability of markets. Markets are formed by the interplay and conflicts between different organizers. In section 6 we point out some different types of organizers, including buyers and sellers. In the last section we take up a few problems for further research on market organization. 2. Market and organization! So, what is a market? Particular markets may have many and various characteristics but it is possible to discern a few elements that are fundamental or constitutive for the institution of market: without these elements most people would not think it was a question of a market or at least not a ”true” market. There have to be a minimum of characteristics for us to conclude that we are observing a market – there are a number of necessary market elements. A market is a social structure for the exchange of owner’s rights. There are two parties exchanging, seller and buyer. They shall have the right to own and the right to buy and sell. In most cultures only individuals and organizations (including states) can have these roles. It should be voluntary to take part in exchanges, i.e. the buyers must want to buy and the sellers want to sell for an exchange to happen. There must also be something to trade - a good, usually consisting of an object, a service or money or other financial instruments. The parties do not have to perceive the goods in the same way but they must perceive it as goods. It is a question of exchange of goods, not gifts or robbery – one party cedes the right of ownership of a piece of goods and in turn gets ownership of another piece of goods. There must be a means of deciding the value of the goods and in a developed economy this normally means that monetary prices must be set. It may be at an auction, such as when buying furniture at Sotheby’s, or as when the price is set in a shoe shop. The most important argument for legitimating markets is to try to point out that they are characterised by competition (Boltanski and Thévenot 2006). By referring to competition one can legitimate sellers’ and buyers’ rights to act as they want themselves: sellers have the right to set what prices they want and sell to whomever 5 they want and buyers in their turn are free to buy or not. Without competition the voluntariness of one of the parties could put the other party in a coercive situation. Competition means that at least three actors have to be in a relationship in which two are on one side and one on the other side of the market. Only in this case can there be a competitive relation between either two buyers of the same goods or two sellers competing for the same buyer. The competitive relation is different than the conflict of interest existing between sellers who want to make as much profit as possible from the thing sold, and buyers who want to pay as little as possible for the same goods or services (Geertz 1992:226.) It is the ”third party” (Simmel 1923), i.e. the one who can benefit from the fact that at least two others are competing for a deal who can profit from the competition. Markets not characterised by competition are difficult to legitimate and lack of competition may also lead to a conviction that there is no market but only a case of barter. A formal organization - a state, a company or an association – is built on the institution Organization. For us to conceive of something as an organization it should show a number of elements and these differ from those of the market. Organizations are constituted by other elements. Organizations are decided orders. Organizations are formed by decisions and in organizations there are decision makers who decide over and on behalf of the members of the organization. The decisions concern, among others, a number of fundamental elements in organizations. One is membership: organizations are not open to anybody but organizations decide who is member or not. There is a hierarchical principle in organizations, i.e. a right to make binding decisions for the members of the organization; however, hierarchy is not an obligation – an organization can also make decisions that are not binding for the members. And members only have to follow decisions within their zone of indifference (Barnard 1938: 168-69.) Inside this zone of indifference organizations may decide on rules for the actions of members. These rules may be made binding for members and rules are very common in organizations. A rule stabilizes actions: it stipulates similar actions in similar situations. Organizations also have the right to monitor its members and they have the right to issue sanctions, both positive and negative. All these elements of organization are fundamental for formal organization – formal organizations have access to them and are also expected to use them (Ahrne and Brunsson 2008.) Organizations are legitimated in 6 a different way from markets: not by the idea of competition but by the idea that members have chosen voluntarily to belong to the organization or because the decision principles or leadership of the organization have been designated in a manner that reflects legitimate values, e.g. democracy or ownership. Described in this way market and organization appear very different from each other but they are in no reasonable sense each other’s opposites and they are not incompatible with each other. The fact that mutual adjustment between parties with high degrees of liberty happens on markets seems to have tempted many to suppose that everything else on markets also is a result of this type of processes in which no one decides on the actions of others; more or less well functioning markets is an unintentional consequence of economic men acting in their own interest. It is assumed that sellers and buyers in a market are not decided by membership but by their voluntary decision to take part or not, that the parties are free to act as they wish in each situation, that they do not expose themselves to control and that there are no other ”sanctions” than the decision of individual parties to interact or not with a particular other agent. But although such markets may exist, it is more common that markets are combined with organization. There is no fundamental opposition between organization and market but these forms may be combined. Many markets have arisen with the help of organization and markets are regularly exposed to various attempts at organization. Something may be highly organized and still be regarded as a market. Markets are organized in different ways. We shall begin by discussing completely organized markets and then proceed to those who are partially organized. 3. Completely organized markets The fact that contemporary economists make a sharp distinction between market and organization and assume that markets appear naturally is somewhat surprising as their market theory is based on Walras’ and Marshall’s studies of Stock Exchanges (Aspers 2007). Marshall wrote already in 1920 ”The most highly organized exchange are the Stock Exchanges. As a rule those who deal in it are in effect a corporation: they elect new 7 members as well as the executives of their body and appoint the committee by which their own regulations are enforced” (1920:256-7.) What Marshall noted is that exchanges are formal organizations. Usually, they have the form of associations or companies. As formal organizations they may not only make decisions, they also have access to all fundamental elements of organization. To deal on exchanges one must be a member and membership is decided by the exchange. This means that the exchange is in control of who may deal (although nearly all members deal on behalf of others, their clients.) There is a hierarchy in that decisions may be binding. This possibility to make binding decisions is often used. One decides on membership and decides on a large number of detailed rules such as exactly what goods are to be handled. There are often decisions on detailed rules for classifying goods in fixed and clearly separated groups. One defines different kinds of securities or different qualities of commodities. The rules normally include also how exchanges should be carried out as well as how information should and may be distributed. The Exchange is entitled to control what deals are made and how the members act. It can issue negative sanctions in case breach of the rules is discovered. But as in other organizations the Exchange does not decide on everything the members do. The members are left some areas where they can decide themselves – they have a zone where they are not indifferent. Members may decide themselves when to be sellers and when to be buyers, how much to exchange (although there may be some restrictions) and what prices they are willing to accept. And these prices create competition between members. Without this degree of freedom it would no longer be a market. One might say that the extensive organization of the exchange is a precondition for this freedom. The market is thus an effect of organization. It is interesting to note that it is correctly organized exchanges that can create markets that come closer to the market ideal of economists than all other markets. Walras stressed that ”the markets which are best organized from the competitive standpoint are those in which purchases and sales are made by auction… this is the way business is done in the stock exchange, commercial markets, grain markets, fish markets, etc”(Walras 1954: 83-84.) On an ideal market (Knight 1921:76-81) there are competing buyers and sellers and the role of each individual buyer or seller is marginal and cannot affect how the market works or how prices are formed. The transaction cost is zero and the products are homogenous. These products are changed between operators who can 8 act both as sellers and buyers. The market operators have access to plentiful and equal information. A modern stock exchange fulfils these requirements to a very high degree. Stocks are homogenous; one H&M stock is identical to another. There are rules for the giving out of information and traders with privileged access to more information than others, so called insiders, are subject to special rules. Computerised price mechanisms have been created which increasingly remove personal relations on the floor, increase monitoring and make the cost of a particular transaction minimal. The price of the standardised goods becomes the only information needed and sellers and buyers compete with the price. (Spence 2001.) It is interesting that the creation of such a near perfect market requires much organization. We must ask ourselves if a perfect market presupposes full organization. Another case of markets organized within the frame of a formal organization is the setting up of so-called internal markets in companies or states. The leadership of the organization allows various units to exchange goods against payment from other units. This organizing requires more decisions than those in stock exchanges. In stock exchanges one can let in members who already possess the basic skills of buying and selling. It is a question of selection of such operators. When one creates internal markets the sellers and buyers have to be actively created; units must be provided with some kind of ownership rights, anchored in the rules of the organization, not in those of the state, an accounting system must be set up to measure the flow of resources between departments and assets in each separate department, and there must be decision makers who can decide about purchase and sale. The management of the organization often sets prices in the form of so-called internal prices. Competition is guaranteed because departments also have the right to buy from outside suppliers or from several suppliers within the organization. The actors on internal markets usually act only in one of the capacities as buyer or seller on a specific market. Yet another form of complete organization of markets is cooperative association. One example is economic associations in the farming and forestry sectors. The members ”own” the society but are at the same time its most important suppliers (e.g. of timber) and customers (e.g. purchase of forestry services). In this case some actors who 9 originally were sellers associated and established an organization that functions as buyers. The consumer co-operations are originally associations of buyers who create sellers within their organization. Members decide jointly which goods should be sold, to which prices and in which shops. But the individual member is free to decide what to buy and in which shop and she may also shop from competitive sellers outside the association. Completely organized markets, however, are only a minor part of all markets. Most markets are not organized within the framework of a formal organization. On the other hand, this does not mean that they are not organized at all. They nearly always contain some elements of organization. Such partial organization is the theme of our next section. 4. Partially organized markets A formal organization has access to all the elements of organization we have mentioned above. But the different elements may be used separately or in different combinations outside formal organization. Society contains plenty of partial organization (Ahrne and Brunsson 2011.) By this term we mean that individuals and organizations may use the elements of organization, membership, rules, monitoring, sanctions, and even hierarchy, without being combined in a formal organization. This holds for markets, too, also those outside formal organizations can be, and nearly always are, organized to some extent through combinations of one or more elements of organization. These elements of organization are geared towards different market elements: to goods, sellers, buyers, exchanges, prices or competition. Such partial organization is typical of so called fixed-role markets (Aspers 2011.) They differ from security markets and other ”switch-role markets” in which persons or organizations are sometimes buyers and sometimes sellers, so that some actors are always buyers while others are always sellers. On the clothing market retail-clothing companies are sellers while the clothes consumers are buyers, while the clothing company is a buyer on the labour market of employees. In the market for special steel 10 Sandvik is a big seller while, for instance, mining companies and machine manufacturers are buyers. As we saw above, economic theory was not originally developed for fixedrole markets, and these do not usually function in accordance with how markets called efficient by economists should function. We shall now look closer at the various elements of organization in them. Membership Membership may be used on markets to decide who may appear as a seller in the market, if at all. In the guild system admittance as seller was decided (Commons 1931.) A modern variant is the requirement in some countries or cities to belong to an organization to be able to offer taxi services. Arrangers of market places of various kinds nearly always have to decide who will be allowed to appear in the market – space is limited in the market place or the exhibition hall and furthermore, the arranger will perhaps only allow sellers of particular goods or sellers with particular qualities, for instance especially serious ones. Membership can also be a means of strengthening sellers even though it does not lead to direct exclusion of some potential sellers. Sellers may associate in trade associations, sometimes with the purpose of giving sellers a certain identity as particularly serious or reliable through membership. Sellers on some markets often state in their information material that they belong to for instance, the French Union des Syndicats de l’Immobilier or The Swedish Bar Association. Airline alliances give greater possibilities for coordinating long distance flights between airline companies. On labour markets the existence of strong unions forces employers to negotiate with them rather than with individual employees. Membership in itself is not something positive on a market; it is also about what the organization does in relation to the market. To be a member of a cartel is nowadays not considered a desirable identity; on the other hand cartels can coordinate prices or distribute sales commissions between members in a way that will benefit them and palpably influence the function of the market. 11 Buyers can also be organized through membership. Employers organize in employers’ associations before negotiations with unions. Dissatisfied train commuters create a society whose membership size is an argument and they complain collectively instead of individually. Many sellers are interested in organizing their customers in various ”clubs” that generally do not contain any other element of organization than the membership itself. Airline companies create customer clubs for frequent flyers or for customers whom they hope will become frequent flyers because of the membership. In the last decades the functioning of the aviation market has become strongly influenced by these customer clubs and by airline alliances. Membership may also be used as a means of limiting the number of possible customers although this is unusual and often forbidden by law. Restaurants can be made open only to certain customers by being turned into clubs with membership lists as a way of raising the status of the club and ensure customers about what kind of other customers they are likely to meet. Rules Rules are probably the element of organization of markets that has attracted most attention, particularly state rules but rules of other types and origins are common on markets. They may deal with how products should be designed, how sellers or buyers should be, which prices should apply, or how the exchange should be made. States issue rules about all markets within some territories or even globally. But states can also issue rules that are valid only for specific markets. There are, for instance, rules that regulate which goods may be sold on markets for medicines. Buyers must be of a certain age, an age that may be higher than the age of majority. To deal in firearms the seller needs a special permit and the buyer needs a gun licence. Other organizations also issue rules. As we saw above stock exchange members as well as enterprises listed at stock exchanges, must follow many rules. Trade associations can set up rules that are conditions for membership. Many market rules are standards, i.e. rules that are not binding (Brunsson and Jacobsson 2000.) The rule setter does not force the intended rule followers to follow the 12 rules – because the rule setters are not entitled to do so or because they do not wish to force the followers of the rules. Some state laws are standards. In Sweden the Sale of Goods Act, for instance, is dispositive, i.e. voluntary for the parties. But most standards are set by other organizations than states. National, and increasingly, international standardising organizations, have set a very large number of standards for goods in the last hundred years. There are standards for clothing sizes, screw dimensions, for computer and telephone components. Standards are used to categorise goods into those that comply with standards and those that do not. There are standards for which goods can be counted as safe or environmentally friendly. If many follow the same standards it means in many cases that the possibilities to combine different goods increase. In some areas standards very efficiently limit which goods are offered in the market at all, as is the case for telephone components. It is not meaningful to try to sell components that do not follow established standards and therefore cannot be used in telephones. In other respects standards influence many buyers’ evaluation of various goods, for instance in the case of eco-labelling. Membership organizations for sellers may also develop quality standards to make consumer choices easier, among other things by introducing ”judgment devices”, in other words tools for facilitating for actors on markets to make decisions to act because goods and services can be evaluated (Karpik 2010.) Sometimes standards are developed in organizations that are common to sellers and other interested parties. One example is the Forest Stewardship Council in forestry (Boström 2006.) In other cases standards are defining for goods, for example so called appellations (Karpik 201:45-46.) Champagne must be produced exclusively in the district of the same name and by designated methods. Standards for different qualities of a particular commodity, such as farming products, make it possible for sellers and buyers to interact without the commodity being present. They are able to trust that the commodity complies with the standard. Historically, standards, including the introduction of a standardised means of exchange in the form of money, have been decisive for making it possible to deal in rights on stock exchanges and for the emergence of futures contracts. 13 Standards are also used to categorise sellers and buyers, especially if they are firms. Accounting standards used to judge the economic strength of a firm, belong here, or quality standards, or standards for environmental work or social responsibility governing how the internal work of a firm is administered and which should assure buyers that they are buying from solid, reliable and ethically acceptable sellers; (Botzem.) Standards may concern several parts of supply chains. Standards for fair trade, for example, concern from what type of firm a seller in his turn may buy – a clothing company should not buy its fabrics from sellers using child labour. And as a direct buyer of labour the company should not employ child labour. Monitoring Just like rules organized monitoring is relatively common. There are many who monitor if standards and other rules are complied with on markets. States control market transactions, to collect taxes, to ensure that goods are not dangerous or to maintain competition. But much monitoring is carried out by other organizations. There are other organizations that certify or accredit other organizations. Companies may be certified as quality businesses or as businesses that are socially responsible. Rating institutes such as Standard and Poor’s or Moody’s survey the credit worthiness of businesses. It happens that senior citizens’ organizations decide to systematically survey the pricing of everyday commodities. Newspapers and other media publish and compare prices on consumer commodity markets. Companies may also be investigated on how ethical they are. In many cases monitoring may happen against the will of those monitored, in other cases companies themselves take the initiative to be monitored by applying and paying for a certification. In all these cases an outsider monitors the sellers and the motive is to inform potential buyers so they can make a better choice in some sense. There are examples, however, of cases when buyer and seller have agreed to organize some form of independent monitoring to enable exchange and pricing in the market to work, i.e. to bring about a functioning market at all. One case is so-called timber measurement, which occurs when buying, and selling harvested wood. It is not so easy to measure exactly the amount of wood when the trees are still standing in the forest. 14 The parties have therefore agreed to let independent timber measurers estimate the amount of wood, its quality and thus the prices when the harvested wood is delivered to the buyer. Sanctions Sanctions may consist of rewards and penalties. By organized monitoring one can facilitate for individual buyers, for example, to carry out a kind of sanction by refraining from buying from some sellers or by favouring other sellers. But groups of market operators or outside organizers can also institute sanctions. Such sanctions can be decided without the use of any other element of organization. Organizers decide on sanctions against market operators who do not have to be members and there does not have to be organized monitoring. An organizer can award something he, she or it deems worthy of encouragement. Such a sanction is recognition in the form of awards, e.g. on the book market or the film market. A prize is awarded to show what is considered a meritorious achievement, perhaps in the hope that an increase in output and demand of this kind of quality in books and films will follow. Sanctions, not least positive sanctions, are also a means of advertising the awarder of the prizes. An example of organized punishment is a decided boycott of certain goods or goods from certain sellers (Micheletti 2003.) Monitoring is often followed by organized sanctions. Certification of an enterprise can be seen as positive sanction that follows after organized monitoring, refused certification as a negative sanction. The scrutiny of companies from an ethical standpoint by media can lead to listings in which some are pointed out as particularly bad. In this way the brand is denigrated. A bad report in a food guide can kill a restaurant while a good review can keep it fully booked for weeks ahead. Hierarchy Hierarchy may be used by formal organizations. This means that the leadership of the organization use their right to make decisions that are binding for the members. Breach of such decisions may ultimately lead to expulsion from the organization. As we have pointed out, hierarchy is often put in opposition to market. But markets contain many hierarchical elements. It is common to point to states in this context. States are 15 organizations that can decide on membership, rules, monitoring, and sanctions that will be binding for the actors on different markets. States can, for instance, force sellers to sell to certain buyers: large producers or wholesalers cannot simply refuse to sell to certain retailers. But which state shall offer hierarchy is not always a given thing. In international trade it is common for sellers and buyers to agree that hierarchy should settle disputes and which hierarchy should take precedence, which court or other arbitral institute that should be applied to. This principle can be traced back hundreds of years to the development of Lex Mercatoria, principles for trade, which governed economic transactions even between merchants from different countries and without direct state intervention (Volckart and Mangels 1999.) Not only states establish hierarchy on markets. Organizations for sellers or buyers may do it as well. In such organizations hierarchy means that individuals or organizations voluntarily have ceded the right to make decisions on some of its actions to somebody else. They have the possibility to make decisions on rules, monitoring, and sanctions that the members are forced to follow as long as they wish to continue as members. The members of a trade association may, for instance, be made to follow certain ethical rules, and they may be forced to permit monitoring and accept sanctions, e.g. to pay damages. In cartels, such as those on the labour market, the rules may concern which prices can be accepted. A trade association can also decide how competition should be. NHL decides, for instance, that the teams that have done poorly in the previous season get to choose new players first, before the better teams in the post-season draft. It is not a matter of course, however, that trade associations are able to use the hierarchical principle in practice very often. It is usually meta-organizations, i.e. organizations in which the members themselves are also organizations. Such organizations often find it difficult to make binding decisions on questions that are controversial among members (Ahrne and Brunsson 2008.) Instead they use standards, voluntary control, and avoid negative sanctions. Markets are differently organized Even though it is unusual for markets to be organized in one single formal organization such as a stock exchange, nearly all markets contain elements of organization. It is easy, 16 however, to observe that different markets are organized to varying degrees and in different ways. The market for clothing is differently organized than the market on groceries or train transports. The rental market is differently organized than the labour market. Different elements of organization are used to a varying degree and they organize the different market elements to a different extent. Partial organization is not necessarily the same as an unequivocal order. As there are different interests behind the organization there may also be different rules and different forms of monitoring and sanctions in one and the same market. The point is, however, that markets cannot be explained without looking at how they are organized and that changes in the form of market exchanges always occur in interplay with different types of organization. What is the significance of market organization? What consequences does organization have for how markets develop? 5. Consequences of organization To emphasise organization on markets does not imply a denial of other processes by which order is created. The effects different elements of organization give rise to can be reached by other processes, above all by the mutual adjustment often held to be significant for markets (Lindblom 2001) or the development of special cultures on markets (Aspers 2011.) It is not only decided memberships that rule the access to a market. Economists have pointed at other obstacles to access. Access to markets may also be limited because everybody does not have resources enough to buy, to manufacture or to sell. The corresponding differences are valid for other elements of organization. The non-decided correspondence to rules is norms that are developed on markets and to a large extent differ between different markets (Aspers 2011.) Nonorganized monitoring consists, for instance, of the consumers’ daily monitoring of goods and prices in various shops. And the most important sanction on most modern surplus markets is the buyers’ refusal to buy from some sellers because their products or prices 17 are not accepted. All these forms are different than the corresponding elements of organization. Sellers and buyers make a large number of decisions about their own actions on markets, e.g. about what to sell or buy. However, elements of organization are decided and those decisions affect others than only those who make them. Therefore, organizing decisions must also be communicated to others and thus achieve a greater visibility and publicity than the decisions the individual sellers and buyers make on their own behalf. Elements of organization thus get a different attention than market elements. The decision aspect of organization has several important consequences (Ahrne and Brunsson 2011): decisions are attempts, decisions create a form of uncertainty, decisions give explanations, they stress the importance of specific decision makers who are responsible for the decisions and they call attention to the possibility that people can influence the situation. As decisions on different elements of organization are about what others shall do there is a potential gap between the contents of the decision itself and what will happen; there is an uncertainty whether the decision will be followed or not. Organization is therefore always an attempt, but it is a question of attempts that have been publicized. Those who have made such a decision have also stated what they want others to do. It can therefore be seen if this succeeds or fails and such failures often become more visible than ordinary market failures. This may be one reason why it is often said that organization destroys markets. At the same time decisions can lead to greater transparency in that they are always visible. Decisions also imply that there have been options and a decision can therefore be questioned; why was this option chosen instead of another; other members could have been chosen, rules could have been formulated differently, etc. It is therefore easy to question the design of various elements of organization. 18 Decisions are in themselves attempts to create certainty and predictability and to stipulate how the nearest future will turn out. At the same time uncertainty is created (Luhmann). Through a decision a particular option has been selected before another and thereby is shown that there are in fact options. Thus an organized order always involves some instability – it may change and may change fast. Decisions are made by specific individuals or organizations that become responsible for the decision and its consequences. Consequently, there is also somebody to turn to if one is dissatisfied with a decision. For every element of organization there is somebody responsible. For that part of the market that is the result of mutual adjustment or development of a culture, the responsibility is highly diluted. There are many buyers and sellers but none of them are responsible for the market itself. There is instead talk about “market forces”. All in all, these consequences of organization combine to make elements of organization visible and attract attention. In this way focus is moved from market elements to elements of organization. If one is dissatisfied with something on a market it is common to direct one’s complaints to organizers rather than to individual sellers or buyers; one complains of environmental organizations which issue eco-labels, trade associations that lay down guiding principles or states that make laws. At the same time criticism against organization often leads to new decisions being made for others and the result is more organization. To change a market generally requires fairly much organization. Even the idea of “setting the market free” leads to demands for organization. In some cases this idea leads to an extreme amount of organization. A case in point is today’s European train transport market (Alexandersson.) Markets are often described as highly dynamic. But much of the dynamics is created by organization. To the extent that a market is organized it is also unstable and quick changes cannot be excluded. Organizers strive to stabilize the market on their conditions 19 but cannot guarantee the result. The mutual adjustment most often leads to slower changes. Those who analyse the consequences of mutual adjustment on markets have shown great interest in possible equilibriums. But when organization is concerned there is no equilibrium that guarantees stability. Precisely therefore is it common that market actors dream of and ask for so called stable rules of the game. But because it is a question of rules of the game they can change very suddenly and it is difficult to predict when and how. The organization of a market typically leads to a compromise, not to efficiency – it is unlikely that the organization of a market should be the unambiguously most efficient solution of anyone’s problem. Rather than emerging as functions of different kinds of goods that necessarily will generate different forms of market organization, single markets are temporary and the not particularly stable results of a struggle between many people and organizations with different interests (cf. Weber 1978). The rules of the game are rarely the fulfilment of the dreams of anyone particular. All this has implications for how we can understand and explain markets. They can partially be explained by reference to organizers who have appeared, met with resistance and support and by the fact that some organization has succeeded and some other has failed. To understand why markets look in a particular way just now one must analyse different organizers, their interests and chances of influence. In the next section we will look at important market organizers. 6. Organizers of the market There are a large number of market organizers and there is reason to distinguish between some major categories. Sometimes, not least in so-called regulation research the role of states is particularly stressed and is contrasted to “private” or “nongovernmental” regulation. But states have many roles on markets and we will instead make another classification of the market organizers. We discern three major categories – Others, profiteers and market actors. They all use organization to try to change the market order that has been created by others’ 20 organization efforts, by in the market mutual adjustment or by cultural development. But their roles and motives differ. “Others” Modern society contains a growing number of private individuals and organizations we might call “others”, i.e. persons and organizations that claim not to act in their own interest but in that of others or even all. (Meyer). They do not act themselves but offer views and advice on how other people and organizations should act. One group of others that has attracted special attention in the research on how markets are organized are economists. This research has often been called performativity theory (Callon 1998a), since the theoretical statement on how a market should be organized, i.e. the theory, is the template for how real markets are organized. Economic sciences have not only studied markets but also developed models for what properties markets should have, e.g. in the form of the ideal market which we described above. By the increasingly central role of the social sciences they no longer are a mirror of the laws of society, but can instead be viewed as an integral part of its own object of study (Latour 2005.) Economists have also succeeded in influencing the organization of quite a few real markets (Callon 2007; e.g., Callon, Millo, and Muniesa 2007; MacKenzie and Millo 2003.) The economic theories that have had an impact have been very general and dealt with markets at large. There are also “others”, more interested in the function of specific markets. Some markets are supposed to give rise to negative so-called external effects, for instance, in the form of environmental pollution, injustice, health problems, moral decay, or misery in general (Satz 2010.) Markets are culturally prominent today, and moreover, in many cases ethically controversial (Satz 2010); there is hardly anyone today without an opinion on sweatshops in publicly well-known industries like coffee and clothes (Aspers 2006; Micheletti 2003; Stehr, Henning, and Weiler 2006.) Such markets attract many “others”. The external effects constitute the basis of legitimacy of proposals for re-organization of problematic markets or even proposals that goods dealt in them should no longer be traded at all. Those who wish to organize markets for this reason can join in associations, for instance, environmental movements or temperance societies. Although 21 these organizations have more purposes than organizing markets they sometimes are examples of organizing buyers through membership. Members may be exhorted to buy only certain goods from certain sellers. Another strategy is to set standards for goods, a possible strategy for influencing what is sold. Such standards can state which goods are acceptable and which are not. It is often possible to combine it by some kind of monitoring. This is the case when approved goods are marked with certain symbols, as for instance eco-labels or fair trade labels. Sometimes sellers are compared to standards. Sellers who do not confirm to certain rules may be sanctioned by boycotts. Various “others” have different chances to influence the organization of markets. When they wish to strengthen their influence they often approach states or organizations with states as members. Economists try by moulding public opinion or by lobbying to influence states to organize markets in the way they think is the correct way. Economists have often been engaged by states to design rules for how to organize markets. OECD is a well-known organization of states in which economists both survey how different states organize their markets and issue standards for how markets can be “better” organized. The EU also uses economic experts to create the so-called inner market, which among other things is built on comprehensive standardisation, and action plans for competition (Fliegstein 2008.) In a similar way, organizations such as environmental movements often wish that their organizing could be made into imperative laws, with legal sanctions upheld by states or associations of states. They may also want states to set up rules for buyers, for instance in the form of age limits, or some kind of approval as a licence to buy firearms or through membership in a club or that the exchange itself should be organized, for instance, by rules on opening hours, spatial allocation and design. States as organizations are often a medium for various interest groups to influence markets, states thus become one “other” among several. The central role of states for explaining the emergence and form of markets (Fliegstein 2001) should be understood in the light of their unique position and concomitant power to organize markets. Following various forms of globalization states have got a different and often weaker 22 role. This has led to an increased transnational organizing of states but also to greater scope for non-governmental “others”, not least for those with transnational agenda. States also have other roles in the market. They are always large buyers and often also sellers in select markets. They also have an economic interest in markets. Profiteers of the market One of the historically most important motives for states to organize markets has been to make money. States have organized markets to make it possible and more efficient to collect taxes. Instead of buyers and sellers dealing with each other without outside intervention, states and princes have established market places to gain control over the economic life (Masschaele 1992.) To be able to hold a market was almost identical to being a prince (Weber 1998:163.) Weber argued, “princes … wished to acquire taxable dependents and therefore founded towns and markets” (Weber 1981:132.) Others, too, wish to make money on markets and have an interest in influencing their organization. Brokers are an example. Brokers act in the market as representatives of buyers or sellers. On the stock exchange each side has its own representative, while on property markets and in the case of auctions there is one representative who handles the relation for both parties. There are different variants for what side that bears the costs, and to what degree. It is thus a case of two combined markets. On one primary market there is exchange of, for instance, stocks, property, or antiquities. On the other market brokers and auction houses compete for their clients’ commission to sell or buy. It is a market that is parasitic on the primary market in that it can exist only if the primary exists. At the same time the establishment of a parasitic market means that the primary market will be differently organized, with other sellers or buyers or because existing sellers and buyers will acquire the competence of a broker, for instance. Sellers on the parasitic market have an incentive to make sure there are many deals on the primary market. Brokers and auction houses rarely take any great risks, as they never own the securities or the properties; they are only intermediaries. They live on the volume of deals for which they will get commission. It is in their interest that markets are organized so that volumes are maintained, regardless of whether prices go 23 up or down. Agents for players, models, photographers and other services also occupy this structural position. Further examples of organizers who make money on markets are consultants who help sellers to translate standards to the sellers’ specific conditions, or who offer certificates or help with certificates. Such consultants often work very actively to bring about standards, their look, and they thus contribute to and form much of this kind of standardization (Tamm Hallström.) They live on the fact that it is often easier to make people agree on abstract rather than concrete standards; thus many standards are not too explicit and concrete but need to be interpreted. . Another example of market profiteers are media who attract readers by watching over markets by testing various consumer goods, writing film reviews or rating the service of different airline companies (Karpik 2010.) They help customers by scanning the market but they also set the standard for what is a good bargain, directly or indirectly. Common to all market profiteers is that they have double interests, on one hand they want a market that functions well to be attractive for others, but they do not want to make themselves superfluous. They have thus often reasons to unite to organize the market in order to make it an attractive marketplace. Sellers Thus, sellers and buyers act on markets that are to a large extent organized by others. As there is voluntariness they may step in and out of markets. But most sellers cannot simply go from one market to another; if one sells cars it is not so easy to switch to selling butter. On the labour market those who sell their labour encounter similar blocks. Instead of exit they therefore often use voice. They may react against the organization of others by supporting some organization and oppose others. Moreover, they can more pro-actively organize the market they themselves are working on. Large companies are well-known and important lobbyists and opinion-makers with decided views on market organization. They operate singly but above all through various metaorganizations that together can form entire systems (Andersson 2011; Fries 2011.) 24 These meta-organizations can create organization among their members and influence organization decided by others. A central uncertainty problem meeting sellers in a market is competition. The pressure of competition can be diminished through organization. One method is for the seller to organize buyers with the help of membership. The single seller also has the opportunity to diminish its uncertainty and arrange the competition with the help of other elements of organization. Price cartels are examples of attempts to remove the price as a factor of competition. Standardization of the merchandise is an attempt to exclude its characteristics or at least certain of its qualities from competition. By setting standards for different components in a good, a seller can make sure what characteristics buyers will be interested in at the same time; this will not be dependent on sudden changes on the part of buyers or competitors. In lines of business with fast product development sellers put great effort into making standards for their goods. Systems of standardization and certification of sellers is one means of diminishing the number of competitors and make them more equal. In this way one can increase predictability – both by increasing the predictability of present competitors and decrease the risk for new competitors to appear all of a sudden. Sometimes a trade association and rules for membership in it have a similar effect. But at the same time the organization itself is a source of uncertainty. Buyers Many of the “others” that try to organize markets refer to the circumstance that ultimately they work in the buyers’ interest. And everybody is a buyer of consumer goods at least. It does happen that people engage in organization in their capacity as buyers. They have often, but far from always, an interest in promoting competition among sellers. They can create more or less complete organization such as the cooperative movement. They can form consumer associations that make demands on sellers and producers and survey some goods. Another example is initiatives to boycott particular goods or sellers. One way of analysing buyers’ interests is to look at what is called transaction costs (Williamson 1981.) The concept of transaction costs refers to costs in the form of time, 25 efforts, and uncertainty a buyer has to find what he wants on a market. Primarily one can distinguish three types of such costs: search and information costs, bargaining costs and policing and enforcement costs (Williamson 1981.) Variations in transaction costs may occur because of the accessibility of a piece of goods, what form it has and how it should be delivered; if it is something that will be delivered for a longer stretch of time, for instance, an education or a treatment of some kind. It may also concern difficulties to judge the quality of the goods. Several of the market organizers we have distinguished above argue that they decrease the buyers’ transaction costs. For enterprises like stock exchanges, brokers, or auction houses, diminished transaction costs for others are an important part of their business concept. Precisely by a division of interest can the more fundamental problem of trust on markets be solved; as owners of rights you have a business partner (broker) you can trust and do not have to build up trust from the start for every single transaction. Competition between exchanges to tie up clients is primarily about transaction costs and what services they can offer their clients apart from buying and selling securities. Consultants of various kinds make money by decreasing their clients’ transaction costs by monitoring or sanctioning sellers by certificates or ranking. These consultants often estimate to what extent sellers and buyers follow certain standards. Here it is much about diminishing the so-called policing and enforcement costs. Auction houses deal in unique items, such as antiques or art objects that cannot be standardized. But by arranging auctions an enterprise can organize purchase and sale to decrease the transaction costs for their customers, for search and information costs as well as bargaining costs. According to the original theory of transaction costs (Williamson 1975), too high transaction costs will make organizations that are dependent on buying something on a market, e.g. commodities or a particular type of services or labour, include the production of the commodity or service in the own organization. In the theory organization (called “hierarchy”) and market are alternative solutions. If, however, one understands organization as combinations of elements of organization, it will be possible to modulate the picture. 26 First, one does not have to see organization as opposed to market but can see how different elements of organization instead can be a precondition for or simplify market exchanges. Second, one can see that there are several different combinations of elements of organization that make markets more or less and differently organized. Their organization influences the transaction costs and thereby the buyer’s cost estimate. A highly organized market diminishes the buyer’s incentive to incorporate production of the goods in his own organization. Third, and most important, incorporation is not the only means of organizing. To diminish the transaction costs a company may try to influence the organization of the market instead. The choice is thus not only between buying and producing but organizing may instead lead to organization in order to be able to buy simpler and safer on a market. The great engagement of some companies in standardization work, their demands for certification of their suppliers and their lobbying of states and other organizations, can partly be understood as attempts to influence their transaction costs. At the same time these organizational activities come at a cost just like incorporation into the own organization (Williamson 1985:162), which may explain why companies do not always choose organization alternatives before status quo. In standardization theory one has pointed out that smaller firms (as well as consumers) rarely have enough resources to be on an equal footing with, or able to take part at all, in international standardization work (cf. Djelic and Quack 2007.) 7. Questions about organization and market This paper has combined two literatures. The first is the economic sociological literature about markets. This literature has touched upon organization of markets only to a limited degree. The other literature is the literature on organization. It has only touched upon markets to a limited degree. We have shown the fruitfulness of combining these two literatures, to enable us to better understand how markets are organized and how they become organized. 27 Classical economists and sociologists seem to agree that an efficient and well functioning market requires a high degree of organization but what exactly they mean by organization is often unclear. We have discussed the organization of markets from a concept of organization that is wider than only comprising formal organizations but narrower than embracing all order or active ordering. By breaking down the concept of organization into different elements a better analysis is feasible as well as a deeper understanding that markets are organized and how they are organized. Organization is more than hierarchy or rules. To put market against hierarchy runs the risk of hiding essential elements of the organization of markets. The same risk exists when one speaks of the regulation of markets. And it is definitely not exclusively, or even mainly, states that organize markets. There are many market organizers. The elements of organization and the market elements can be combined in different ways. Existing markets are organized to different degrees and in different ways. Common for all market organization is that it provides space for buyers and sellers with some form of free choice, and that there is competition on either or both sides. Organization of markets does not mean that they will be eliminated. On the contrary, organization is often a central element to bring about a market or to change a prevailing market structure. An organizational perspective on markets also gives rise to new research issues. During the last half-century scholars have put a number of fundamental questions about how formal organizations are constructed and function. Most of these questions can also be asked about the organization of markets but can be expected to yield different answers. A comprehensive question is how organization can contribute to create markets. What do such processes look like and what decides if a market arises and why it gets a particular organization from the beginning? Are there, in spite of the modern faith in markets, still areas that are especially difficult to organize as markets and how are such difficulties overcome? Why are not all markets organized like stock exchanges? One might also ask who the organizers of the market are and how they appear. Most organizers are formal organizations and knowledge about them is necessary for 28 understanding how they operate. We have distinguished between “others”, profiteers, and market actors and demonstrated that they have partly different functions and characters. But are there other or more detailed subdivisions that are more relevant and clarifying? Organizers can be expected to have different interests and values. Some wish to maximize their own profits, others wish to promote efficiency or ethics, while still others worry about the impact of markets on environment or distribution. What conflicts arise between these organizers and how are they handled? The instruments for solving conflicts on markets seem to be fewer than in organizations. To what extent and in what way are conflicts about market organization solved and to what extent do they persist? Why are some interests and values dominant on some markets? How does the organization of markets change? As in the case of formal organizations, there are many who wish to reform markets with various arguments. Sometimes such reforms are attempts to rectify previous reforms that one dislikes; at other times they are reiterations of reforms that have not had the wanted impact. Sometimes they are reactions to the perception that markets have developed in a negative way due to other processes than organization. From where do the ideas for these reforms come and what possibilities to learn from experience exist? What influences the transition from organization to institution and vice versa? As all organization consists of attempts the question of its effects becomes central. What effects do different elements of organization or combinations of them have in different situations? Is it more difficult to organize some elements of the market than others? Are there strategies that organizers use that is more successful than others? Under what circumstances can market organization be institutionalised? Taken together the answers to such questions may elucidate issues of power and responsibility on markets. Who gets power over the market organization? Formal organizations concentrate responsibility while markets dilute it to a higher degree. What effects do different degrees and types of market organization have for the division of responsibility for markets? 29 The answers can also elucidate the comprehensive question of to what extent markets are ruled by mutual adjustment, institutions, or organization, and how these forms interplay? The answers to all these questions are, of course, interesting in their own right. They may also be compared to the answers given about formal organizations. Such a systematic comparison can be used as a research strategy to generate further and more precise questions and answers. But the comparison also has a value of its own. Formal organizations and markets are the central forms of the economy and it is important to better understand the differences and similarities between them. And the difference is not that one is organized and the other is not. 30 References (incomplete) Abolafia, Mitchel. 1996. Making Markets. Cambridge Ma.: Harvard University Press. Ahrne, Göran and Nils Brunsson. 2008. Meta--Organizations. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. —. 2011. "Organization Outside Organizations: The Significance of Partial Organization." Organization 18:83-104. Arrow, Kenneth. 1974. The Limits of Organization. New York: W.W. Norton &Company. Aspers, Patrik. 2006. "Ethics in Global Garment Market Chains." Pp. 287-307 in The Moralization of the Markets, edited by N. Stehr, C. Henning, and B. Weiler. London: Transaction Press. —. 2011. Markets. Cambridge: Polity Press. Barnard, Chester. 1938. The Functions of the Executives. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press. Boltanski, Luc and Laurent Thévenot. 2006. On Justification, Economies of Worth. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Burt, Ronald S. 1988. "The Stability of American Markets." The American Journal of Sociology 94:356-395. Callon, Michel. 1998a. "Introduction: The Embeddedness of Economic Markets in Economics." in The Laws of the Market, edited by M. Callon. —. 1998b. "The Laws of the Market." Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. —. 2007. "What Does It Mean to Say That Economics is Performative." in Do Economists Make Markets? On the Performativity of Economics, edited by D. MacKenzie, F. Muniesa, and L. Siu. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Callon, Michel, Yuval Millo, and Fabian Muniesa. 2007. "An Introduction to Market Devices." Pp. 1-12 in Market Devices, edited by M. Callon, Y. Millo, and F. Muniesa. Oxford et al.: Blackwell Publishing. Commons, John. 1931. "Institutional Economics." The American Economic Review 21:648-657. Djelic, Marie-Laure and Sigrid Quack. 2007. "Overcoming Path Dependency: Path Generation." Theory and Society 36:161-186. Dodd, Nigel. 2005. "Reinventing Monies in Europe." Economy and Society 34:558-583. Fligstein, Neil. 2001. The Architecture of Markets, An Economic Sociology for the TwentyFirst Century Capitalist Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press. —. 2008. Euroclash, The EU, European Identity, and the Future of Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Fligstein, Neil and Iona Mara-Drita. 1996. "How to Make a Market: Reflections on the Attempt to Create a Single Market in the European Union." The American Journal of Sociology 102:1-33. Frank, Robert. 1985. "The Demand for Unobservable and Other Nonpositional Goods." The American Economic Review 75:101-116. Geertz, Clifford. 1992. "The Bazaar Economy: Information and Search in Peasant Marketing." Pp. 225-232 in The Sociology of Economic Life, edited by M. Granovetter and R. Swedberg. Boulder: Westview Press. Hall, Peter and David Soskice. 2001. Varieties of Capitalism, The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 31 Hayek, Friedrich von. 1973. Law, Legislation and Liberty, A New Statement of the Liberal Principles of Justice and Political Economy, Volume 1, Rules and Order. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. —. 1988. The Collected Works of Friedrich August Hayek, Volume I, The Fatal Conceit, The Errors of Socialism. London: Routledge. Karpik, Lucien. 2010. Valuing the Unique: The Economics of Singularities. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Knight, Frank. 1921. Risk, Uncertainty and Profit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. Korpi, Walter. 1983. The Democratic Class Struggle. London: Routledge & Keegan Paul. Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor Network Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lindblom, Charles. 2001. The Market System: What It Is, How It Works, and What to Make of It. Yale: Yale University Press. Luhmann, Niklas. 1982. The Differentiation of Society. New York: Columbia University Press. —. 1988. Die Wirtschaft der Gesellschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. MacKenzie, Donald. 2009. Material Market: How Ecnomic Agents are Constructed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. MacKenzie, Donald and Yuval Millo. 2003. "Constructing a Market, Performing Theory: The Historical Sociology of a Financial Derivatives Exchange." The American Journal of Sociology 109:107-145. Marshall, Alfred. 1920. Industry and Trade, A Study of Industrial Technique and Business Organization; of Their Influences on the Conditions of Various Classes and Nations. London: Macmillan. Masschaele, James. 1992. "Market Rights in Thirteenth-Century England." The English Historical Review 107:78-89. Micheletti, Michele. 2003. Political Virtue and Shopping. Individuals, Consumerism, and Collective Action. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan. Polanyi, Karl. 1957. The Great Transformation. Boston: Beacon. Satz, Debra. 2010. Why Some Things Should Not Be for Sale: The Moral Limits of Markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Simmel, Georg. 1923. Soziologie, Untersuchungen über die Formen der Vergesellschaftung. München und Leipzig: Duncker und Humblot. Smith, Adam. 1981. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Indianapolis: Liberty Press. Smith, Charles. 2007. "Markets as Definitional Practices." Canadian Journal of Sociology 32:1-39. Spence, Michael. 2002. "Signaling in Retrospect and the Informational Structure of Markets." The American Economic Review 92: 434-459. Stehr, Nico, Christoph Henning, and Bernd Weiler. 2006. "The Moralization of the Markets." London: Transaction Press. Walras, Léon. 1954. Elements of Pure Economics, or The Theory of Social Wealth. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. Weber, Max. 1978. Economy and Society, An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Translated by G. R. a. C. W. e. 2.volumes. Berkeley: University of California Press. —. 1981. General Economic History. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. —. 1998. The Agrarian Sociology of Ancient Civilization. London: Verso. White, Harrison. 1981. "Where do Markets Come From?" The American Journal of Sociology 87:517-547. 32 —. 2002a. "Markets and Firms: Notes Toward the Future of Economic Sociology." Pp. 129-147 in The New Economic Sociology, Developments in an Emerging Field, edited by M. Guillén, R. Collins, P. England, and M. Meyer. New York: Russel Sage Foundation. —. 2002b. Markets from Networks, Socioeconomic Models of Production. Princeton: Princeton University Press. —. 2008. Identity and Control, How Social Formations Emerge. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Williamson, Oliver. 1975. Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implication. New York: Free Press. Volckart, Oliver and Antje Mangels. 1999. "Are the Roots of the Modern Lex Mercatoria Really Medieval?" Southern Economic Journal 65:427-450.