MUMMIES. The dream- Attachment

advertisement

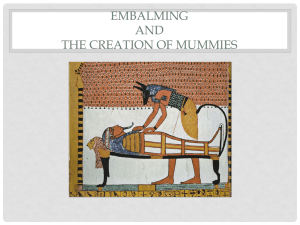

MUMMIES. The dream of everlasting life exhibition of the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology/Bolzano in cooperation with the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museums/Mannheim On mummies and mummification Why and in which circumstances are mummies formed? What do they tell us about the living conditions in the past? By which scientific methods is it possible to draw their secrets from them? Mummification A mummy is formed when the natural decomposition process of a cadaver is inhibited. Such bodies do not follow the natural cycle and are preserved due to particular chemic, physic and climatic circumstances. A distinction should be made between natural/accidental and artificial/intentional mummification. Intentional mummification suggests the use of embalming or preparation techniques or the intentional laying out of a body in a natural milieu that favours mummification. For many years the term mummy was only applied to embalmed corpses from Ancient Egypt. Following Napoleon’s Egyptian Campaigns of 1798-1801 a veritable wave of Egyptomania swept across Europe, ushering in the serious scientific study of mummies. In modern usage a mummy can be an animal or human body in which – unlike skeletons – the soft tissue has been preserved. Mummies are invaluable witnesses of their time. Nowadays state-of-the-art research methods have revealed keys to the living conditions and dietary habits, evidence of diseases and much more. Natural and artificial milieus Natural mummification in caves In caves natural mummification also occurs thanks to constant temperature and humidity. Absolute darkness inhibits the growth of bacteria and slows the decay of dead organisms, whilst air circulation through shafts and crevices dries them out. Mummies have been found in caves in desert areas as well as in Siberia. Natural mummification is possible even in damper caves in Central Europe as a result of air drying. 1 Mummification in desert areas In desert areas, whether cold or hot, bodies are frequently naturally mummified. The aridity and wind quickly strip a dead organism of all its fluid. The desiccated body surface, whether covered in hair or hairless, resists bacterial attack and does not re-absorb any moisture. Sand with a high salt and natron content further accelerates the desiccation of bodies that have been mummified in desert sand. Dry mummies are not always equally well preserved. Decomposition can continue inside the body due to its fluid content, and the organs decay. Natural mummification in ice In the glacial areas of polar and mountainous regions natural mummification is possible in two ways: A combination of high humidity and low oxygen converts body fat into adipocere, which envelops the skeleton and conserves the body. Or an icy cold and dry environment can remove crystallized water from the body so that the soft tissue is freeze-dried. In this process not all the moisture is removed, which is why these mummies are called wet mummies. (e.g. Ötzi). In permafrost areas the ice dries out the ground in which the body is lying and prevents decomposition. Natural mummification by salt Salt can occur in solid or dissolved form. Solid salt is found in salt deserts or underground. Salt has the property of binding water. The body dries out, bacterial growth is inhibited and the corpse eventually mummifies. Salt mummies can also occur in damp environments. In salt lakes and seas salt penetrates the body tissue thanks to a high salt concentration in the water, displacing the water and dehydrating the body’s cells. Natural mummification in bogs Bogs are depleted of oxygen due to the constant excess of water from rain or groundwater. Plant remains are only partially decomposed and form peat sediments. Bodies can be preserved in bogs thanks to the lack of oxygen, the presence of acidity and an antibacterial substance in peat moss (sphagnum). However, a substance called a polysaccharide which is released when a plant dies plays the most important role. It removes calcium carbonate from dead organisms, which bacteria need for growth. A tanning process also occurs, which preserves skin, nails and organs. Natural mummification in artificial milieus Natural mummification does not occur only in natural surroundings. It can also occur in manmade environments such as cellars, attics, ventilation shafts and power station stacks. Natural mummification requires dry air and is also favoured by a continuous air flow and temperature stability. 2 Mummies in the world Egypt In the graves of the Ancient Egyptian culture the desert sand dehydrated the bodies, which then mummified naturally. The first attempts to artificially preserve corpses were probably based on this observation. Once the Egyptians started to build tombs in the Early Dynastic Period (ca. 3000 BC), the environment for natural mummification was lost. They were then forced to preserve their dead artificially. The cult of the mummy was based on the Egyptian belief in the afterlife. To guarantee life after death, the body had to be preserved so that the soul “ba” could return to the body and enjoy a carefree existence in the hereafter. Asia Naturally and artificially mummified bodies have also been found in Asia. The majority of them come from desert areas, where the body was preserved naturally thanks to the extreme aridity of the environment. In wetter areas the dead were preserved with the help of special techniques and burial customs. Deliberate utilization of the natural environment and artificial preservation techniques show that in Asia too people felt a need to preserve bodies as intact as possible. South America The extensive desert areas on the Pacific coast of South America and the remote Andean peaks provide optimum conditions for the preservation of organic substances. In the grave fields on the coast, thousands of bodies from pre-Columbian culture groups underwent natural mummification. In some cases indigenous people deliberately used the favourable climate conditions to bury their dead, because preserving the human body was an important cult for Andean culture groups. They perceived death as a transformation of the soft tissue into a hard immutable material, in which their ancestors continued to live. Mummies in Europe The prehistoric cultures of Europe did not practise any artificial mummification of their dead. Bodies underwent mummification as a result of the natural environment (the bog bodies or Ötzi, for instance). Elaborately prepared bodies from Egypt, which characterized the idea of the mummy, came to Europe in the late Middle Ages along with medical knowledge from the Orient. Whole shiploads of mummies reached the harbours of the Occident and were made into medicines. A second import wave was unleashed by Napoleon’s Egypt Expedition at the beginning of the 19th century. This time the mummies kindled a fascination in the mysterious arts of Ancient Egypt. 3 In the Middle Ages only the bodies of emperors, kings and popes were embalmed. In subsequent centuries the custom of preserving bodies spread to the rich and nobles precipitated by the long period of laying out during elaborate ceremonial funerals. The internal organs that were removed were embalmed and sometimes buried separately from the body. Crypts in churches were much coveted as a final resting place, because relics kept in churches were said to bring salvation to the dead. Also in the 20th century people went on believing that the vitality of powerful people continues to radiate as long as the body is preserved remained – this was the idea behind the mummification of people from politics and public life. Lenin, for example, has been lying in state in a mausoleum in Red Square in Moscow since 1925. Even Eva Perón, Argentina’s First Lady, who died in 1953, was embalmed. But a military coup prevented her from being buried in an opulent mausoleum. The romantic odyssey of her body only ended in 1976 in the La Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires. Mummification today Countless people still want to preserve their body for eternity, even today. Mummification can be an alternative to burial or cremation and can be used for teaching and research purposes or to fulfill a dream of one day being brought back to life. Bodies today are mummified in a similar way to methods employed in Ancient Egypt. A more modern process is plastination. After removing endogenous fat and water with acetone and replacing it with plastics, the embalmed body is shaped as desired and cured. With the neuro option, the brain is cryogenically frozen in the hope that some day a new body can be grown from the brain cells by means of DNA replication. South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology via Museo 43, I-39100 Bolzano, Italy phone +39 0471 320100, fax +39 0471 320122 web www.iceman.it, email museum@iceman.it authorized for publication, please quote the source please send a deposit copy to patrick.gasser@iceman.it 4 MUMMIES. The dream of everlasting life exhibition of the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology/Bolzano in cooperation with the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museums/Mannheim Pictures and picture copyrights Picture copyrights will be given at no cost to the press solely and exclusively for the publication of the images in news coverage of the exhibition MUMMIES. The dream of everlasting life hosted in the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology from March 10th to October 25th 2009. All other uses are not permitted. We kindly ask you to precisely state your source and provide free deposit copies for the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museums and the picture copyrights holder(s) after publication. On demand we send high resolution pictures per email or cd. Ancient Peruvian mummy Inca Period, 1000 – 1532 AD South America/Peru Native American Collection, Archaeology and Ethnology Study Collection of the Native American Dept. of Bonn University (D) © Bonner Altamerika-Sammlung Universität Bonn, photo W Rosendahl Mummy and the coffins of Nes-pa-ka-schuti Ancient Egypt, Third Intermediate Period, ca. 650 BC Necropolis of Akhmim, Egypt Lippian Museum, Detmold (D) © Lippisches Landesmuseum Detmold, foto-dpi.com Grave goods of a Pre-Columbian mummy Chancay Culture, Peru, 15th century Reiss-Engelhorn-Museums, Mannheim, (D) © Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen Mannheim, foto-dpi.com 5 Howler monkey Gran Chaco, Argentina Schleswig Holstein Museum Found., Gottorf Palace, Schleswig (D) © Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf Woman with two children Pre-Columbian Period, 1000–1400 AD South America Reiss-Engelhorn-Museums, Mannheim, (D) © Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen Mannheim, photo J Christen Michael Orlovits (1.765-1806) Dominican Church of Vác, Hungary Hungarian Natural History Museum, Department of Anthropology, Budapest (H) © photo B Szandelszky Man from the Exloërmond Bog Iron Age, 2nd to 4th century BC Exloërmond, Netherlands Drents Museum, Assen (NL) © Drents Museum Assen 6 Skeleton of a child 3.600 – 3.400 BC Gebelein, Egypt Museo delle Antichità Egizie, Torino © Museo delle Antichità Egizie, Torino – foto-dpi.com Mummy of Imhotep Vezir of Thebes Egypt, 18th Dynasty, 1504 – 1492 BC Museo delle Antichità Egizie, Torino © Museo delle Antichità Egizie, Torino – foto-dpi.com The Iceman Copper Age, 4th millennium BC Hauslabjoch, Italy South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, Bolzano (I) © South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology Reconstruction of the Iceman South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, Bolzano (I) © South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, photo Andree Kaiser South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, Bolzano (I) © South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology For images of the Iceman/South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in high resolution please contact Melitta.Franceschini@iceman.it 7 8