Student Perceptions of the

advertisement

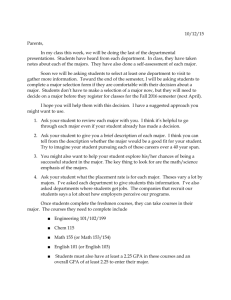

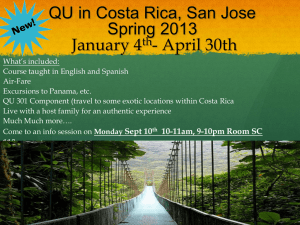

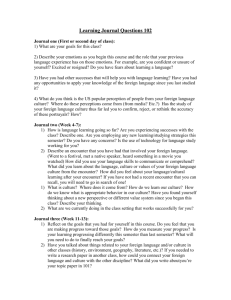

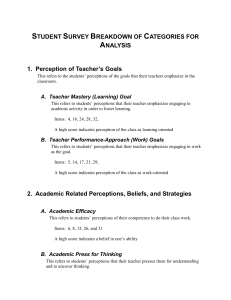

The First Course in Accounting: Students’ Perceptions and Their Effect on the Decision to Major in Accounting by Marshall A. Geiger Associate Professor of Accounting E. C. Robins School Of Business University of Richmond 28 Westhampton Way Richmond, VA 23173 804/287-1923 mgeiger@richmond.edu or geigerma@notes.cba.ufl.edu and Suzanne M. Ogilby Professor of Accounting School of Business Administration California State University—Sacramento 6000 J Street Sacramento, CA 95819 916/278-7157 ogilbysm@csus.edu DRAFT: July 10, 2000 Please do not quote without permission. We would like to thank the instructors that took part in this study, the participants at the 1998 American Accounting Association Western Region and Annual Meetings, Lamont Steedle, the reviewers, and the editor, Jim Rebele for comments on earlier drafts of the paper. We also thank Christine Yap for her data assistance. The First Course in Accounting: Students’ Perceptions and Their Effect on the Decision to Major in Accounting ABSTRACT Little empirical evidence exists regarding students’ perceptions of the first course in accounting and the effect of these perceptions on deciding whether or not to major in accounting. The purpose of this study is to begin examining student perceptions regarding the first accounting course and how those perceptions relate to selection of accounting as a major. The study separately examines initial perceptions and changes in perceptions over the semester for intended accounting and non-accounting majors, and assesses the association of individual accounting instructors with changed student perceptions. We then examine the relationship between perceptual changes, final grades, and individual instructors on decisions to major in accounting. Responses from 331 introductory financial accounting students from two universities indicate that while intended accounting majors perceived the course more favorably than nonaccounting majors at the beginning and end of the semester, both groups exhibited relatively positive attitudes toward the course. However, these attitudes were similarly less favorable by the end of the course for both groups. We also found evidence of the important role individual instructors play regarding changing student perceptions and selection of accounting as a major. The analyses for selection of accounting as a major indicate that the decision depended on initially intending to major in accounting, performance in the first course, and individual instructors, but not on changes in perception regarding the first course. The First Course in Accounting: Students’ Perceptions and Their Effect on the Decision to Major in Accounting INTRODUCTION The Accounting Education Change Commission (AECC), and several other groups within the accounting profession (e.g., AAA, 1986; Arthur Andersen & Co. et al. 1989) have identified the first course in accounting as a critical educational component for not only accounting, but for all business majors (AECC, 1992). In addition to these formal organizations, various individual accounting educators have discussed the role of the introductory course in the accounting and business curriculum (e.g., Cherry and Reckers, 1983; Baldwin and Ingram, 1991; Pincus, 1997; Vangermeersch, 1997). The importance of this first course lies in its ability to both present useful accounting information that can lead to better business decision-making for all business majors, and attract, or discourage, individuals from becoming accounting majors. The AECC (1992) has also argued that the first course in accounting is critically important for its potential impact on student perceptions regarding the accounting profession and an individual’s chances for success as an accounting professional: The course shapes their perceptions of (1) the profession, (2) the aptitudes and skills needed for successful careers in accounting, and (3) the nature of career opportunities in accounting. These perceptions affect whether the supply of talent will be sufficient for the profession to thrive (pp. 1-2). The implied mandate of the AECC, as well as previous calls from within the profession, appears to be based partially on the potential of the first course to affect student perception - or what has generally been referred to as the affective domain of education (Krathwohl, Bloom and Masia, 1964; Wilson, 1988). To date, however, no empirical evidence exists as to what perceptions students actually hold toward the first course in accounting and the impact of their perceptions on selection of accounting as a major. For example, before students enter the course, do they believe that the course will be useful? Rewarding? Boring? Do intended accounting 1 majors perceive the first accounting course differently than their non-accounting peers? Do students’ perceptions about the course change over the semester? Do students with positive changes in perception choose to become accounting majors? This study begins to empirically investigate student perceptions regarding the first accounting course, including changes in those perceptions throughout the semester. The study also examines changes in perception across individual instructors and the relationship of perceptual changes with students’ decision to major, or not major, in accounting. PRIOR LITERATURE A significant number of studies have been conducted to address various aspects of the introductory accounting course. Among other things, these studies have examined the determinants of student performance in the first accounting course (Eskew & Faley, 1988; Doran, Bouillon and Smith, 1991; Wooten, 1998), the possible effect of gender on accounting course performance (Buckless, Lipe and Ravenscroft, 1991) and the prediction of student performance in upper-level accounting courses based, in part, on performance in the introductory courses (Danko, Duke and Franz, 1992; Bernardi and Bean, 1999). There has also been a sizable amount of research and discussion on the appropriate content of the first accounting course (e.g., Cherry and Reckers, 1983; Baldwin and Ingram, 1991; AECC, 1992; Cherry and Mintz, 1996; Pincus, 1997; Vangermeersch, 1997). The summaries of accounting education research presented by Williams et al. (1988) and Rebele et al. (1991, 1998), however, reveal that no empirical study has performed a direct assessment of accounting students’ perceptions regarding any individual accounting course. Nor has any study performed an assessment of the relationship between course perceptions and major selection. 2 A study by Friedlan (1995) asked Canadian accounting students both at the beginning and end of the course the perceived importance of 12 skills on their ability to perform well in introductory accounting, and the importance of 13 skills for performance as accounting practitioners. While the Friedlan study assessed students’ perceptions of the skills needed to perform well academically and professionally, it did not directly assess students’ perceptions of the introductory accounting course itself. There has also been some empirical research concerning how various categories of instructors (e.g., accounting, business) view the first course in accounting (e.g., Cherry and Mintz, 1996) and on students’ general perception of accounting, accountants, and the accounting profession (e.g., Paolillo and Estes, 1982; Cory, 1992; Cohen and Hanno, 1993). However, studies involving student perception in accounting typically ask students one or only a few attitudinal/perceptual questions at the end of the course. These studies then compare responses to these few items across groups of students exposed to different pedagogy during the course (e.g., Daroca and Nourayi, 1994; Saudagaran, 1996; Hill, 1998). Accordingly, these prior studies have incorporated attitudinal questions, but have not adequately addressed student attitudes. Additionally, there have been several studies that have attempted to examine whether the introductory accounting course has the ability to attract “the best and the brightest” students to accounting (e.g., Inman, Wentzler, and Wicker, 1989; Baldwin and Ingram, 1991; Adams, Pryor, and Adams, 1994; Nelson and Deines, 1995; Riordan, St. Pierre, and Matoney, 1996). Riordan, et al. (1996) examined whether the introductory course appeared to attract or retain quality students (as measured by GPA). They found that the mean GPA of intended accounting majors was higher than that of non-accounting students before the introductory course, and that students transferring into accounting after the course had higher GPAs than those transferring out. These 3 results suggest that the introductory course may retain quality students and may actually attract higher performing students to major in accounting. A study by Cohen and Hanno (1993) used the theory of planned behavior to predict and explain the choice of accounting as a major. Their results indicate that students chose not to major in accounting because they perceived it to be too number-oriented and boring. Intended accounting majors were also found to place more emphasis than intended non-accounting majors on high performance in the introductory courses in their selection of a major. In a related study, Stice et al. (1997) categorized students as being “qualified” or “unqualified” to major in accounting based on performance in the introductory course. Their results indicate that course performance was not significantly related to the decision to major in accounting when examining just the “qualified” (i.e. high performing) students. That is, just because a student performs well in introductory accounting does not mean that they will choose to major in accounting. Their results are consistent with those of Adams et al. (1994) who found that students’ responses to the item “genuine interest in the field,” as opposed to actual course performance, was the most significant factor in deciding to major in accounting. However, none of these prior studies present a direct examination of student perceptions toward the introductory accounting course and how these perceptions relate to the decision to major in accounting. Stice et al. (1997) argue that while performance may serve as a screening device, future research should focus on identifying non-performance factors that affect the decision to major in accounting. Further, no study in accounting has examined the possible differential effect of individual instructors on students’ decisions to major in accounting. Although prior researchers (e.g., Daroca and Nourayi, 1994) have inferred that there may be a differential impact of individual faculty members on introductory accounting students, this conjecture has not been tested empirically. 4 Affective Domain Students’ perceptions regarding the first course in accounting can generally be considered to be part of the larger affective domain of education (Krathwohl et al. 1964). While student learning occurs in both the cognitive and affective domains (Bloom et al. 1956; Wilson, 1988), the affective domain encompasses learning objectives that “emphasize a feeling tone, an emotion, or degree of acceptance or rejection” (Krathwohl et al. 1964, 7). Such learning objectives are often expressed as interests, attitudes, perceptions, values, emotions, or appreciation. While these objectives differ from cognitive domain objectives (e.g., the aspects of knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation), they are nonetheless closely related to learning (Bloom et al. 1971) and to the selection of a major area of study (Adams et al. 1994). In fact, Munsterberg (1914) argued almost a century ago that: “The chief motive of human actions lies in feelings and emotions. If education is to secure certain actions, the safest way will be by developing certain likes and dislikes, pleasures and displeasures, enthusiasms and aversions” (p. 196). According to Krathwohl et al. (1964), the affective domain is comprised of five stages and begins at the level of receiving or attending in which the student is simply sensitized to the existence of a particular phenomenon. The second level of the hierarchy is responding, in which the student is somewhat committed to the phenomenon so that he or she will pursue involvement in it. Valuing, the third level of the hierarchy, indicates that the student believes the phenomenon has worth. The fourth and fifth levels of the hierarchy are attained as the student has increasingly positive internalized values relating to multiple phenomena and begins the process of organizing those values and integrating them into a total philosophy. While the last two affect levels, organizing and integrating, are important for higher order learning within any discipline, their assessment in introductory accounting students, including 5 intended accounting majors, is somewhat premature. Accordingly, this study presents a general assessment of the first three affect levels and attempts to examine students’ general perceptions, values, expectations, and attitudes about the first course in accounting and how these perceptions are related to the decision to major in accounting. Based on the existing literature discussed in this section, we examine the following research questions in this study: Q1 What are students' initial perceptions regarding the introductory accounting course? Q2 Do intended accounting majors have different initial perceptions compared to non-accounting majors? Q3 Do students' perceptions of the introductory course change over the semester? Q4 Do changes in students’ perceptions differ across individual instructors? Q5 How are students’ perceptions and course performance related to the decision to major in accounting? METHOD Instrument The instrument used to assess students’ general perceptions toward the first accounting course was a self-report, paper and pencil questionnaire administered during class in the first and last weeks of the introductory financial accounting course. The questionnaire contained ten statements regarding students' perceptions of the course across a variety of affect dimensions. Questionnaire items cover varying aspects of the first three affect levels (Krathwohl et al. 1964), and were adapted from questions used in an earlier pilot study on introductory accounting students (Watkins and Ogilby, 1996). We also included an item regarding students’ perceptions of how important their instructors are in affecting their opinion of the course. In addition, as an 6 overall reflection of students’ perceptions of their ability to do well in the course, instruments at the beginning and end of the course asked students their expected grade. The list of items presented to students at the beginning of the semester is presented in Table 1. Students responded to the ten perception statements on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree (“5”) to strongly disagree (“1”). Students indicated their expected course grade for the final item, which was then converted to a five-point scale. --Insert Table 1 Here-- The end-of-semester instrument contained the same items as presented in Table 1, except that items were reworded where necessary to reflect past tense. The only exception was that item number five (LOOK/ENJOY) was modified from "I am looking forward to this course" at the beginning of the semester to "I have enjoyed this course" at the end of the semester. Irrespective of the arguments presented by the AECC (1992) concerning the general business usefulness of the first accounting course, the first two items (i.e., COURSES and CAREER) were anticipated to be perceived as more valuable, a priori, by students intending to be accounting majors. The remaining items were felt to be more neutral with respect to selected major and to be potentially equally applicable to all students. However, due to the natural tendency of students to perceive a course in their major more positively than non-majors, we separately examine responses over the semester for accounting and non-accounting majors. The first instrument also collected demographic data such as gender, GPA, SAT scores, and intended major as of the start of the course. Since the vast majority of students in the study were first semester sophomores, several students (n = 77) had not yet decided on a specific 7 business major at the time of first administration.1 These undecided students were classified as non-accounting majors, and to a large extent represent the pool of students intended to be influenced by the first accounting course to possibly consider accounting as a major (AECC, 1992; Cohen and Hanno, 1993). We then examined subsequent student records for evidence of major selection immediately after the course. University records are available by semester and indicate the intended major of the student, which was required for registration purposes. Accordingly, we were generally able to identify subsequent selection of a major for students immediately following the course, including those originally undecided at the beginning of the course. Subjects Student participants in this study were enrolled in introductory financial accounting (i.e. the first required accounting course) in two medium-sized public universities in the United States during the fall semester. We included universities from two different geographic areas (i.e., east coast and west coast) to get a broader representation of accounting students in the United States. All sections of introductory financial accounting at the two universities participated in the study. Additionally, eight different instructors (four from each university) taught these students, and all used a fairly "traditional" lecture/discussion format.2 Neither university used “mass lecture” sections during our study. While the content covered in these courses was typical of an introductory financial accounting course, and coordinated within each university, faculty had the usual latitude in material sequencing, presentation, emphasis, assignments, and student testing and evaluation. In order to assess changes in perception and the impact of perceptions on selection of a major, students that did not respond to instruments both at the beginning and end of the semester 8 were eliminated. We also eliminated students for which we could not obtain final grades or selection of a major data subsequent to the course (e.g., student received an incomplete or withdrew from school). These requirements resulted in 331 students (117 and 206 from the two universities) who properly completed both instruments and for which all data were available.3 Of the 331 students, 175 were males, 45 indicated at the beginning of the semester that they intended to major in accounting, and 53 students selected accounting as their major immediately after the course. RESULTS Table 2 presents demographic data for intended accounting and non-accounting majors at the beginning of the course. As seen in the table, there was no difference in overall GPA between accounting and non-accounting majors, but accounting majors had higher SAT-math scores and lower SAT-verbal scores (p<.01) than non-accounting majors. --Insert Table 2 Here-- Q1 and Q2 – Initial Perceptions of Intended Accounting and Non-Accounting Majors Table 3 presents a summary of responses to the ten perception items, as well as to the question asking the student's expected grade for the course. Results are presented separately in the table for the intended accounting and non-accounting majors. An examination of the first two columns of Table 3 shows that the overall mean responses of both the intended accounting and non-accounting majors is generally above the neutral point of 3.0 (based on our 5-point 9 scale) for the positive items and under 3.0 for the negative (i.e., BORING) item. Results related to research question one, therefore, indicate that both intended accounting and non-accounting majors had a favorable initial perception of the introductory accounting course. --Insert Table 3 Here – To more directly address the second research question regarding perceptual differences between intended accounting and non-accounting majors, we performed 11 separate unbalanced ANCOVA models using the initial responses to the 11 perceptual items as the dependent variable, accounting/non-accounting major indications as the classification variable, and GPA as the covariate (to control for general academic ability).4 The results of these models are reported in Table 3. As expected, accounting majors initially perceived the course more positively than non-accounting majors on seven of the 11 perception items. With the exception of nonsignificant differences for the DIFFICULTY, BORING, INSTRUCTOR and EXPGRADE items, the accounting majors perceived the introductory accounting course in a generally more positive light than did the non-accounting majors at the start of the semester. Q3 – Changes in Perception The third and fourth columns of Table 3 present mean results as of the end of the semester, and the last two columns of the table indicate the mean changes in responses for the semester separately for the intended accounting and non-accounting majors. To examine the third research question, a within-persons t-test was run for each of the 11 items presented in Table 3 for the beginning-of-semester versus the end-of-semester responses for the combined group of accounting and non-accounting majors. This t-test procedure matches end-of-semester 10 responses to beginning-of-semester responses for each individual to determine if individuals have changed their perceptions over the semester. The results for all 331 students indicate that, with the exception of the INSTRUCTOR analysis, students did generally change their perceptions over the semester (p<.01). As shown in Table 3, when the sample is partitioned and separately analyzed according to intended major, identical change results were found for the non-accounting majors (i.e., differences on all items except INSTRUCTOR), but a few differences were noted for the group of intended accounting majors compared to the aggregate results. Only five of the eleven items (i.e., COURSES, REWARDING, BORING, MOTIVATED and EXPGRADE) were significantly (p<.05) changed over the semester for the accounting majors. The intended accounting majors were therefore relatively more stable in their perceptions regarding the introductory accounting course as compared to the non-accounting majors. However, an examination of both the end of semester mean responses and the changes in mean responses over the semester indicates that both intended accounting and non-accounting majors generally had slightly less favorable perceptions of the introductory course at the end of the semester as compared to the beginning of the semester. To assess differences between accounting and non-accounting majors on final perceptions, we again ran 11 separate unbalanced ANCOVA models, with GPA as the covariate, for the end of semester responses. We also performed a similar set of analyses on changes in perceptions in another set of 11 models using changes in perceptions as the dependent variable. Results of these models are reported in Table 3, both for the end of semester analyses and analyses of the change in perceptions over the semester. 11 As seen in columns three and four of Table 3, differences between intended accounting and non-accounting majors still existed at the end of the semester for five of the seven items where differences were noted at the beginning of the semester. Further, columns five and six indicate that the aggregate changes for the semester were relatively consistent between intended accounting and intended non-accounting majors. The only significant difference in the amount of changed perceptions between the two groups was that the intended non-accounting majors increased their response to the TIME item significantly more than the intended accounting majors (p<.05). Otherwise, the changes in perceptions over the semester were very similar between the two groups of students. Changes in responses to the BORING item represent the largest change in an item for the semester. The mean response for both groups at the end of the semester indicates that students generally "agree" (i.e. means of almost 4.0 on the 5-point scale) with the statement that the course was boring. The only item that became more favorable toward the end of the semester was the item for whether students looked forward to/enjoyed the course (LOOK/ENJOY). While intended accounting majors essentially remained stable on this item, the non-accounting majors indicated improvement in this area. Thus, while non-accounting students’ perceptions regarding other aspects of the course decreased, they increased their response to the overall enjoyment question. 5 Q4 – Perception Differences Across Instructors Our study involved a total of eight full-time accounting faculty - four from each institution. To assess the fourth research question regarding whether changes in student perceptions over the semester differed across individual faculty members, we used unbalanced ANCOVAs with instructor the independent variable6 and the change in perception on each of the 12 items in Table 3 the dependent variable in 11 separate analyses. To control for changes being due to initial response level, we used students’ initial response as a covariate in each of the 11 models.7 The results of the separate analyses are presented in Table 4. -- Insert Table 4 Here -All ANCOVA models presented in Table 4 were significant at conventional levels.8 The results provide fairly strong evidence that changes in students’ perceptions did differ across the eight instructors. Specifically, all but three of the 11 models exhibit a significant difference among instructors on changed perceptions over the semester at the .10 level, and five of the 11 models indicate significant differences between instructors at the .05 level. These results provide evidence regarding a relationship between individual instructors and changes in student perceptions during the first accounting course. Q5 – Selection of Accounting as a Major To assess the last research question regarding the relationship between student perceptions and selection of accounting as a major, changes in perceptions for the semester were regressed on a student’s decision to major in accounting (coded 0/1) immediately following the course. In order to account for the effect of a student’s initial selection of major, possible course performance, and instructor influences on their subsequent major selection, we included accounting major selection at the beginning of the semester (coded 0/1), actual final grades, and the teacher indicator variable in the regression. Results of the logistic regressions are presented in Table 5. --Insert Table 5 Here – The regression results indicate that the most significant (p<.05) predictors of students deciding to major in accounting after the introductory course were their initial selection of 13 accounting as a major, their final grade, their individual instructors, and whether students increased their perception of the usefulness of the course to their careers and their indications of boredom. Additional Analyses To assess whether students who did not finish the course had similar initial perceptions as those who did finish (i.e., a survivor bias in the data), we performed t-tests comparing students used in the study with students for which we only have beginning-of-semester data (n=256).9 This is a crude comparison because some students in this latter group undoubtedly remained in the course, but did not attend the class in which the second questionnaire was administered. The results of the t-tests indicate that these two groups were similar on all demographic variables, but that students not completing the second questionnaire were significantly lower in their initial perceptions on the COURSES, CAREER, and LOOKING/ENJOY questions (p<.05). Thus, students not attending class at the end of the semester exhibited more negative perceptions of the introductory accounting course at the beginning of the semester. To further assess whether changes in student perceptions over the semester were a function of student aptitude, we correlated changes in responses over the semester for the 11 items with GPA (for the students providing that information). The results indicate that the only changes in perceptions that were significantly correlated (p<.05) with GPA for the entire group of students were changes for the INSTRUCTOR, TIME and EXPGRADE questions. The significant negative correlation of GPA and the changes in INSTRUCTOR question indicate that lower GPA students had larger increases in response to this item. The significant positive correlation of GPA with the changes in TIME question indicates that higher GPA students had 14 larger increases than lower GPA students in their perception of time spent on the course by the end of the semester. The significant positive correlation of GPA with the changes in EXPGRADE question indicates that higher GPA students had smaller reductions than lower GPA students in their expected grade by the end of the semester. With the exception of these three items, overall changes in students’ perceptions were not significantly related to student GPA. To examine some possible causes of the general instructor effect found in our study, we first identified several instructor and course characteristics. Specifically, we identified the gender of the instructor, what type of examinations they used (multiple-choice questions, problems, or both), whether the course was taught during the day or at night, how many times the course met a week, how many sections of the introductory course were being taught by the instructor that semester, and highest degree held (Masters or PhD). We then ran sets of t-tests for the dichotomous categories (e.g., male/female; day/night, etc.) and unbalanced ANCOVAS for categories with more than one classification (e.g., type of examination, number of sections taught, etc.) on all 11 perceptual changes for the semester. The overall results of these additional analyses generally indicated no discernable pattern of changes in perception due to any specific instructor or course characteristic. While no significant results (p<.05) were found for most analyses, the results for number of class meetings per week indicated that meeting three times a week significantly increased the changes in perceived time (TIME) devoted to the class, as well as decreased the changes in perceived difficulty (DIFFICULTY), compared with classes that met only twice a week. A further analysis of mean changes in perceptions for the 11 measures across the eight instructors indicated that the instructor associated with the highest degree of positive changes in perception (highest on four 15 measures, second highest on two measures, and third highest on one measure) was a male instructor holding a masters degree that taught one section at night (twice a week) who used both multiple-choice and problem type questions on examinations. Similarly, a search for an instructor that was associated with the lowest degree of positive changes in perception indicated no clear selection. Several instructors were associated with the most negative changes in perception on two or three of the surveyed items, with a wide disparity of mean results across the instructors. Clearly, the examination of the causes of the significant instructor association are not resolved in this exploratory study. Future research is needed to assess possible instructor and course characteristics that may significantly impact changes in students’ perceptions about the introductory accounting course. Finally, we separately examined the selection of major for the initially undecided students. Of the 77 undecided students in our study, ten subsequently decided to major in accounting after completing the introductory accounting course. We then reran the logistic regression presented in Table 5 without the initial accounting selection variable, on just these 77 undecided students. Results of the regression indicate that the only significant variables were the instructor variable (p=.0195) and the change in perception of boredom (p=.0680). Again, after controlling for all other factors, the individual instructor is shown to have significant association with the decision to major in accounting for these initially undecided business students. While the change in boredom is significant, the sign on the coefficient is negative, indicating that the undecided students deciding to major in accounting show smaller increases in boredom than those choosing not to major in accounting. 16 CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION This study empirically investigated students’ perceptions of the first accounting course. Althought intended accounting majors perceived the course more positively than did nonaccounting majors, our findings generally indicate that both groups of students had fairly positive perceptions of the introductory accounting course across a number of dimensions. We did find, however, that both accounting majors and non-accounting majors had diminished perceptions of the introductory course at the end of the semester compared to the beginning of the semester. The largest perceptual change over the semester was the students’ increased indication of boredom with the course. We also found significant variation in changed student perceptions across individual instructors, as well as for the selection of accounting as a major after the course is completed. Our results also indicate that student perceptual positions at the end of the course are generally not related to selection of accounting as a major, after controlling for course performance, instructor, and initial major selection. While requiring further confirmatory research, our findings of significant individual instructor associations supports the conjecture of Daroca and Nourayi (1994) and reinforces the need for accounting programs, as well as educational institutions, to be selective in their assignment of instructors to the first accounting course (AECC, 1992). Since the introductory accounting course is often a student's first (and potentially only) exposure to accounting, selection of an instructor is critically important and can substantially impact the supply of accounting majors. This study represents an initial attempt to gather information on the affective domain of student perceptions, and requires additional replication work to collaborate our findings. Stout and Rebele (1996) point out that without appropriate replication, generalizing beyond the 17 immediate study may be premature and inappropriate. Accordingly, while we included every student and faculty member involved with introductory accounting at two medium-sized institutions, our use of only two universities should be recognized as a limitation of the study. Finally, our study did not attempt to systematically vary the style or format of classroom presentation that students were exposed to in the introductory course. Nor did it assess individual instructors along any psychological or personal characteristic or dimension (i.e. cognitive or teaching style). Varying teaching methods between the "traditional" lecture/discussion format and other formats, such as case-based teaching, cooperative learning, and using multimedia as a presentation mode, would assist in the evaluation of student perceptions of the introductory course and the decision to major in accounting. Likewise, evaluating the impact of individual instructor characteristics on changing student perceptions appears to be warranted based on our findings. 18 Table 1 Perception Items—Initial Questionnaire 1. This course will help me to do well in my future business courses. (COURSES) 2. This course will help me do well in my career. (CAREER) 3. Doing well in this course would be personally rewarding. (REWARDING) 4. I expect to spend more time on this course than my other courses. (TIME) 5. I am looking forward to this course. (LOOK/ENJOY) 6.. This course will be difficult. (DIFFICULTY) 7. This course will be boring. (BORING) 8. I am highly motivated to do well in this course. (MOTIVATED) 9. I expect to learn a lot in this class. (EXPLEARN) 10. The instructor will affect my opinion of the usefulness of this course. (INSTRUCTOR) 11. What is your expected grade in the course? (EXPGRADE) 19 Table 2 Demographic Variables a GPA SAT-mathb SAT-verbalb Accounting Majors 2.85 577.5 454.8 Non-Accounting Majors 2.84 535.8 487.1 ___________________ a Based on 38 and 255 accounting and non-accounting students, respectively, who answered this question. b Based on 30 and 151 accounting and non-accounting students, respectively, who answered this question. 20 t-test p value .91 .01 .01 Table 3 Summary of Students' Mean Perceptions (Accounting majors - n=45; Non-Accounting majors - n=286) Variable COURSES CAREER REWARDING TIME LOOK/ENJOY DIFFICULTY BORING MOTIVATED EXPLEARN INSTRUCTOR EXPGRADEa Beginning of semester Acctg Non-Acctg End of semester Acctg Non-Acctg Change Acctg Non-Acctg 4.76 4.75 4.82 3.73 4.14 3.74 2.74 4.49 4.57 4.14 3.73 4.51++ 4.61 4.33++ 3.84 4.12 4.00 3.94++ 4.24+ 4.39 4.10 3.23++ -.25 -.14 -.49 .11 -.02 .26 1.20 -.25 -.18 -.04 -.50 4.40** 4.27** 4.49** 3.36** 3.77** 3.77 2.75 4.22** 4.33* 3.96 3.61 4.25++** 4.01++** 3.97++** 3.83++ 3.93++ 4.02++ 3.84++ 3.85++** 4.12++** 4.01 3.02++ -.15 -.26 -.48 .47* .16 .25 1.09 -.37 -.21 .05 -.59 See Table 1 for an explanation of the variables. ____________________ a Based on a scale of 1 to 5. + Significantly different than the beginning of semester responses based on within-persons t-test at p<.05. ++Significantly different than the beginning of semester responses based on within-persons t-test at p<.01. * Significantly different than the accounting majors at p<.05. ** Significantly different than the mean for accounting majors at p<.01. 21 Table 4 Individual Instructor Influences - Summary of ANCOVA Models (All majors - n=331) (All models significant at p<.0001) Dependent Variablea: Change in COURSES CAREER REWARDING TIME LOOK/ENJOY DIFFICULTY BORING MOTIVATED EXPLEARN INSTRUCTOR EXPGRADE W/Initial Position as Covariate Type III SS Model F Teacher p-value 27.80 .018 17.21 .189 17.06 .354 49.34 .016 33.67 .208 44.61 .001 77.52 .058 20.16 .081 5.69 .069 48.23 .002 4.87 .005 See Table 1 for an explanation of the variables. ____________________ a The Type III SS p-value indicates the impact of adding the teacher variable to the model last, after the covariate is already included. 22 Table 5 Logistic Regression--Selection of Accounting Major (All majors - n=331) Independent Variable Intercept COURSES CAREER REWARDING TIME LOOK/ENJOY DIFFICULT BORING MOTIVATED EXP LEARN INSTRUCTOR FINAL GRADE INITIAL MAJOR TEACHER Coefficient F-value P-value -2.406 -0.016 0.970 0.295 -0.149 0.016 -0.099 0.441 0.179 -0.093 -0.208 0.327 3.646 -0.491 20.746 0.002 7.796 0.995 0.475 0.004 0.227 4.822 0.423 0.077 0.873 8.354 48.663 16.593 .0001 .9621 .0052 .3185 .4908 .9505 .6338 .0281 .5154 .7808 .3501 .0038 .0001 .0001 Model F = 119.013; p-value = .0001; df=13. 23 REFERENCES Accounting Education Change Commission. (1992). The First Course in Accounting: Position Statement No. Two, Issues in Accounting Education, 7(2): 249-251. Adams, S. J., L J. Pryor, and S. L. Adams. 1994. Attraction and retention of high –aptitude students in accounting: An exploratory longitudinal study. Issues in Accounting Education 9(1): 45-58. American Accounting Association (AAA). Committee on the Future Structure, Content and Scope of Accounting Education (The Bedford Committee). 1986. Special report: Future accounting education: Preparing for the expanding profession. Issues in Accounting Education 1(1): 168-193. Arthur Andersen & Co., Arthur Young, Coopers & Lybrand, Deloitte Haskins & Sells, Ernst & Whinney, Peat Marwick Main & Co., Price Waterhouse, Touche Ross. 1989. Perspectives on Education: Capabilities for Success in the Accounting Profession. New York: Authors. Baldwin, B. A., and R. W. Ingram. 1991. Rethinking the objectives and content of elementary accounting. Journal of Accounting Education 9(1): 1-14. Bernardi, R. A. and D. F. Bean. 1999. Preparer versus user introductory sequence: The impact on performance in Intermediate Accounting I. Journal of Accounting Education 17 (2-3): 141-156. Bloom, B. S., M. D. Engelhart, E. J. Furst, W. H. Hill, and D. R. Krathwohl. 1956. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives:The Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay Company, Inc. Bloom, B.S., J.T. Hastings, and G.F. Madaus. 1971. Handbook on Formative & Summative Evaluation of Student Learning. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc. Buckless, F.A., M.G. Lipe, and S P. Ravenscroft. (1991). Do gender effects on accounting course performance persist after controlling for general academic aptitude? Issues in Accounting Education 6(2): 248-261. Cherry, A. A., and S. M. Mintz. 1996. The objectives and design of the first course in accounting from the perspective of nonaccounting faculty. Accounting Education—A Journal of Theory, Practice & Research 1(2): 99-111. Cherry, A. A., and P. M. J. Reckers. 1983. The introductory financial accounting course: Its role in the curriculum for accounting majors. Journal of Accounting Education 1(1): 71-82. Cohen, J., and D. M. Hanno. 1993. An analysis of underlying constructs affecting the choice of accounting as a major. Issues in Accounting Education 8(2): 219-238. 24 Corey, S. N. 1992. Quality and quantity of accounting students and the stereotypical accountant: Is there a relationship? Journal of Accounting Education 10(1): 1-24. Danko, K., J.C. Duke, and D. P. Franz (1992). Predicting student performance in accounting classes. Journal of Education for Business 67(5): 270-274. Daroca, F. P., and M. M. Nourayi. 1994. Some performance and attitude effects on students in managerial accounting: Lecture vs. self-study courses. Issues in Accounting Education 9(2): 319-329. Doran, B. M., M.L. Bouillon, and C.G. Smith (1991). Determinants of student performance in accounting principles I and II. Issues in Accounting Education 6(1): 74-84. Eskew, R.K., and R.H. Faley (1988). Some determinants of student performance in the first college-level financial accounting course. The Accounting Review 63(1):137-147. Friedlan, J.M. (1995). The effects of different teaching approaches on student perceptions of the skills needed for success in accounting courses and by practicing accountants. Issues in Accounting Education 10(1): 47-63. Graves, O.F., I.T. Nelson, and D.S. Deines (1993). Accounting student characteristics: Results of the 1992 Federation of Schools of Accountancy (FSA) Survey. Journal of Accounting Education 11(2): 311-225. Inman, B. C., A. Wenzler, and P. Wickert. 1989. Square holes: Are accounting students wellsuited to today’s accounting profession?, Issues in Accounting Education 4(1): 29-47. Krathwohl, D. R., B. S. Bloom, and B. B. Masia. 1964. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives:The Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook II: Affective Domain. New York: David McKay Company, Inc. Mintz, S.M., and A. A. Cherry (1993). The introductory accounting course: Education of majors and non-majors. Journal of Education for Business 68(5): 276-280. Munsterberg, H. 1914. Psychology and the Teacher. New York: D. Appleton and Company. Paolillo, J. G. P., and R. W. Estes. 1982. An empirical analysis of career choice factors among accountants, attorneys, engineers, and physicians. The Accounting Review 62 (4): 785-793. Pincus, K. C. 1997. Is teaching debits and credits essential in elementary accounting? Issues in Accounting Education 12(2): 575-579. Rebele, J. E., B. A. Apostolou, F. A. Buckless, J. M. Hassell, L. R. Paquette, and D. E. Stout. 1998. Accounting education literature review (1991-1997), part II: Students, educational technology, assessment, and faculty issues. Journal of Accounting Education 16(2): 179-245. 25 Rebele, J.E., D.E. Stout, and J.M. Hassell. 1991. A review of empirical research in accounting education: 1985-1991. Journal of Accounting Education (Fall): 167-231. Riordan, M. P., E. K. St. Pierre, and J. Matoney. 1996. Some initial empirical evidence regarding the impact of the introductory accounting sequence on the selection of accounting as a major. Accounting Education—A Journal of Theory, Practice & Research 1(2): 127-136. Saudagaran, S. M. 1996. The first course in accounting: An innovative approach. Issues in Accounting Education 11(1): 83-84. Stice, J. D., M. R. Swain, and R. G. Worsham. 1997. The effect of performance on the decision to major in accounting. Journal of Education for Business 73(1): 54-69. Stout, D. E. and Rebele, J. E. (1996). Establishing a research agenda for accounting education, Accounting Education—A Journal of Theory, Practice & Research 1 (1): 1-18. Vangermeersch, R. G. 1997. Dropping debits and credits in elementary accounting: A huge disservice to students. Issues in Accounting Education 12(2): 581-583. Watkins, T. A., and S. M. Ogilby. 1996. The learning expectations of students in their first year of college-level accounting courses. Paper presented at the 1996 American Accounting Association Annual Meeting, Chicago, Ill. Williams, J.R., M.G. Tiller, H. C. Herring, and J.H. Scheiner (1988). A Framework for the Development of Accounting Education Research. Sarasota, FL: American Accounting Association. Wilson, R. M. S. (1988). Applying the case method in accounting: A comment. British Accounting Review 20: 279-286. Wooten, T. C. 1998. Factors influencing student learning in introductory accounting classes: A comparison of traditional and nontraditional students. Issues in Accounting Education 13(2): 357-378. 26 ____________________ 1 T-test comparisons between these undecided business majors and the other non-accounting majors revealed no significant differences (p<.05) on any of the variables reported in the study. 2 One of the researchers taught a section (n=37 students) of the introductory accounting course included in the study. Exclusion of these students from the analyses does not alter the results presented in the paper. 3 T-test comparisons between the two universities were performed on the demographic variables. The only significant difference (p<.05) found was that students at one university had slightly higher mean GPAs (2.98 vs. 2.75). 4 The use of “unbalanced” ANCOVA models in this study adjusts for the difference in group size for the intended accounting (N=45) and intended non-accounting majors (N=286). Further, results of these analyses without the covariate were substantially the same as those reported in the paper with the covariate. 5 The improvement in these scores may also be attributable to respondents indicating what they believe the researchers (and their teachers) wanted to hear – e.g., that they enjoyed the course, as well as being attributable to an overall indication of their satisfaction with both the course and their instructor. Future research is needed to resolve this seeming disparity in changed perceptions. 6 Each teacher was randomly assigned a number from 1-8. 7 Analyses without the covariate in the models produce results essentially the same as those presented in Table 4. Additionally, instead of controlling for initial perception positions, we ran the analyses using final grades as the covariate. Results of these modified analyses are also substantially the same as those presented in Table 4. 27 8 Separate ANCOVA analyses performed on just the non-accounting majors produced results substantively the same as those presented in Table 4. The small number of declared accounting majors for each instructor precluded a similar analysis on just the accounting majors. 9 Additionally, there were 72 students for which we have end-of-semester data and no beginning- of-semester data. 28