shock therapy

advertisement

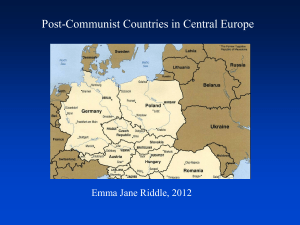

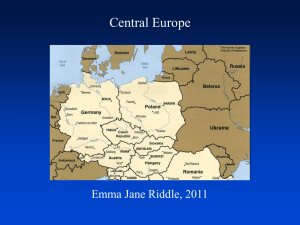

HANDOUT 4 The Economic Dimension of Transition Part I: The Shock Therapy Model Jeffrey Sachs - model of “shock therapy”: an economic theory of transition Based on a globalised, unified capitalist world: this would be brought about by formulating a policy of transformation in Central and Eastern Europe. He created a model of behaviour of the revelant actors and of the ways in which they would interact in certain circumstances faced with their particular constraints and incentives. Various names for this model: Shock Therapy/Treatment Radical Economic Reform Plan the Economic Big Bang Initially supported by US and British policy-makers andmost East European economists advocating reform. The Shock Therapy Model Involved: (Macro-Policies for Restructuring) 1) Breaking-up up of COMECON region, especially breaking-up the C/E Euro countries from the USSR. 2) Making a “root and branch” switch to a particular form of capitalist institutional structure in each state a precondition for normalising relations with that state. 3) Imposing, therefore, a “hub and spoke” structure on the relationship between the West and C/e Euro with each target state in the region relating to the others principally vai its relationship with the Western hub. (American policy between 1990-92 continued to favour the maintenance of a Moscowcentred economic sphere in the Soviet region, except for the Baltic Republics.) 4) Starting the process of regional transformation in the states with the most politically sympathetic governments and then using both negative and positive incentives to extend the required mix of domestic policies across the region as a whole. 5) Western states to provide, in the main through their multilateral organisation, the necessary positive incentives for co-operative governments and constraints for unco-operative governments. 6) The revivial of economic activity in co-operative target states woulf take the form of trade-led growth directed towards Western Europe compensating for COMECON’s collapse. 7) Co-operative states would gain full access to the market of the EC (partly through radically changing some of its key institutional pillars, such as its trade regime and CAP), very substantial economic assistance and eventual membership of an enlarged EU. This approach: a) urged the break-up and in effect the start of a competitive race by E Euro states to prepare themselves for direct entry into the W Euro market; b) rejected mixed or hybrid forms of socio-economic system on the grounds that market socialism had already proved unworkable; HOWEVER, this necessitated radical reform of the EC to accommodate an ‘export surge’ from C/E Euro states and called for an unprecedented degree of funding from co-operative states in the West. By 1990, this overall model was pushed forward as a comprehensive economic strategy for the region as a whole. This was especially favoured because the model was already being used in Yugoslavia and Poland: “Poland will bring in the first comprehensive market-oriented reforms in Eastern Europe.” “The Yugoslav outcome would differ from Poland’s for Yugoslavia would maintain, in large measure, its self-management approach to corporate governance.” (Sachs, 1990) By 1990 this approach was adopted by the G7 states. [Fr-Ger proposals to keep the USSR and C/E Euro linked via a free-trade regime were rejected; Fr proposals for a strategy which would engage in large public infr-structure projects covering the former USSR and C/E Euro were cut-short; a further Fr idea for a pan-European Confederation embracing both the EC and the whole of the East were repudiated. Poland and Yugoslavia were used as examples for a successful way forward.] The path forward, seen by most C/E European supporters of ST lay through the gradual adsorption of the states in the region into the Western economy institutionalised in the various multilateral organisation, especially the EU. Because of this the desired out come was identified as: - a unification of Europe in a single market; - the regional development of prosperous capitalist democracies. - the official projected outcome of ST was to be “democratically-based increased living standards and freedom.” At the base of this transformation was the idea that the post-communist world would have the potential to grow more rapidly than the developed world and thereby narrow the gap in living standards, if the states concerned “harmonised” their economic institutions and joined their economies to the global economic system. The Strategy of ST had: 1) A very paticular institutional “matrix” which included: open trade; currency convertibility; and the private sector as the “engine of growth”. 2) Core reforms that needed to be achieved for the model as a whole to be viable: a) open international trade b) currency convertibility c) private ownership as the main force for economic growth d) corporate ownership as the dominant organisational form for large enterprises e) opneness to foreign investment f) membership of key international economic institutions, including the IMF, World Bank and GATT [Reforms a/b/e/f - were about changing a state’s external politico-economic relations; reform d - was about a particular form of ownership; and reform c - was about what is generally seen as capitalism.] It was argued by the advocates of this strategy that: by joining the rest of the global economy the states of C/E Euro would be able to import some of the prosperity from the rest of the world, usually through the importation of new technologies, organisational patterns, managerial methods and financial capital. Only these could overcome the economic legacy of the previous 40 years. Another core requirement for the success of economic transition was foreign direct investment. In order to get this the strategy called for the creation of a free trade regime and the right institutional and economic conditions in C/E Euro. It was claimed that failure to implement this style of economic strategy (aimed at making a connection with the world economy) would lead to problems such as: an unconvertible currency. an unreformed industrial structure; and a hostile investment climate. [Generally this approach and vision of joining the global economy was a powerful motive for C/E Euro reformers - here again we can look at the examples of Poland and Yugoslavia; also the adapted version used in Hungary and the Czech Republic, and in the early 1990s (1992-93) in Russia through Gaidar’s reforms.] It was explained that such an opening-up of the C/E Euro economies to global capital was the necessary first step for government policy. This kind of policy justified sudden switches to free trade; it justified early convertibility as a means to anchor world prices in the domestic context - thus promoting economic revival through trade; it justified foreign direct investment as indispensible for privatisation and structuring. SHOCK THERAPY It is usually referred to as the 3 “izations”: 1) Liberalization 2) Stabilization 3) Privatization Recently a 4th has been added - Institutionalization As it has turned out in practice - these “izations” progress in a very partcular pattern, covering the interaction of actors with each other and with their environment: 1) the liberalizing/stabilizing shock 2) the international shock 3) privatization and foreign direct investment 4) trade-led growth 5) political/institutional consolidation and growth Shock Therapy, Democracy and ‘Civil Society’ Cardinal goals of ST have been the achievement of democracy and freedom. Although the building of a civil society has not been emphasized, this has been a constant theme of ST supporters. Yet these goals have been treated as ends and not means. As ends, they have been discursively very important because they have been used as core justifications of the means of ST. However, the liberal principle that ends should govern means has been operationally rejected within ST in favour of a more “dialectical” approach: the existing social, legal and political institutions are likely to be resistant to ST, but ST is the only, or best, path to truly democratic, legal and civil institutions, so the existing institutions must be negated from above and outside in order to realise true democracy and civil society. Between 1990-1995 Most governments in post-communist C?E Euro have to some degree tried to lock themselves into the strategy envisaged by ST (especially in terms of the relationships with the global economy) and have tried to combine the demands of the international financial institutional and the EC/EU with often comflicting domestic pressures. Some governments have drifted, without any coherent policy, and only a few, such as Romania, have consciously sought a different road to another form of capitalism. By the mid-1990s The path of progress for ST has proved unstable and many analysts are now criticising this model of economic transition. Although by the beginning of 1996 many analysts do begin to identify an up-turn in the economic climate within the region (things are beginning to stabilise - but is it already too late, politically. So far, 5 major charges are levelled against ST and what it has created in C/E Euro: I that its macro instruments of regional fragmentation and domestic shock change have been immensly costly in the short and medium terms; II that ST free trade-led policy for economic revival was largely misconceived; III ST’s macro policies for sustained economic revival have tended to weaken rather than strengthen long-term revival; IV the practice of ST on the part of Western actors has sharply diverged from the theory in ways that have damaged C/E Eruo states; V in terms of its own criteria, ST has been a failure. The implementation of ST has brought about a “double-depressive-shock” in the region: - part of this has been the result of the ST model’s insistance on the break-up of the COMECON area, rather than maintaining regional trade and production linkages through a customs union and new payment arrangement . . . - part of the shock has come from the implementation of the ST domestic policy cycle . . . All commentators on the region now know about these effects: 1) increased unemployment 2) reduction in real incomes 3) reduction in levels of production IMPORTANTLY, an OECD study entitled “Integrating Emerging Market Economies into the International Trading System” (1994-96) - analysed the state of economic transition in the region, specifically the depression being experienced by the mid-1990s. It pin-points the major causal factors (all deriving from the short-term consequences of ST): I It states that the “stabilisation” aspect, especially the credit squeeze via credit ceilings, was “indentified as the emportant element contributing to the recession, especially at the beginning of the reform process”. II The fragmentation of COMECON-regime trade had a disastrous impact on industrial outpu: “according to some calculation, this volume effect alone can explain most of the fall in output in Hungary and the CSFR and about one third of the decline in Poland”. III Key institutional vacuums, as pointed out by the critics of ST, such as the absence of a financial system, meant that “all countries suffered from an inadequate supply-side response”, in other words a downward spiral into protracted depression. This study, along with others, concluded by the mid-1990s that, dispite a host of arguments presented by ST supporters, the then contemporary situation, the simple undeniable fact, was that the entire ST programme held the depression as its core feature. Similar critiques have also focussed concern in the following areas: 1) the failure of the ST trade regime 2) the failure of the transition economies to gain full acess to the EU market It has been concluded that the tragic result of these politico-economic interactions has been that the domestic depressive shocks, policed by the IMF and designed to lay the basis for an export-led revivial, have largely led these countries up a “blind alley”, prolonging the depression. The origins of the revival, in so far as it has come, has not been led by foreign trade but by domestic consumption. Yet the policies of the international financial institutions have been overwhelmingly directed at reducing domestic demand pressures, stamping out inflation, lowering wages and reducing government deficits through spending cuts. CONSTITUTIONALITY VS SHOCK THERAPY IN RUSSIA The most direct and brutal test of the relationship between liberal principle and ST ocurred in Russia in 1993. The Yeltsin government derived its authority from parliamentary elections held in 1990 during the Gorbachev period. The Russian parliament elected at that time had then elected Yeltsin as president and, in the autumn of 1991, voted hm emergency powers for a year to give him a free hand with econmic transformation. By the autumn of 1992, with real wages down to 40% of their levels at the start of the year, the majority in parliament began to swing against the Gaidar reforms. By the spring of 1993 Yeltsin was on a collision course with the deputies. From the spring of 1993 Yeltsin embarked upon a drive to flout the constitution in order to crush erstwhile supporters within the Russian parliament. The parliament’s powers were not, in fact, very extensive. It could not vote on the government’s programme or pass a vote of no confidence in the PM. It could not approve individual ministers. But on the other hand, it could not be dissolved by the president and it has substantial power over budgetary matters. Faced with parliamentary opposition to his economic programme, Yeltsin decided to announce the dissolution of parliament, an act expressly prohibited in the constitution. When the Mps sought to resist this act by occupying the parliament building, Yeltsin had them surrounded and cut-off, and this led to an ill-judged but constitutionally legitimate effort by the parliament to strip Yeltsin of power. Yeltsin responded to a march on a radio station with a military assault on parliament building. After the defeat of the opposition, Yeltsin also imposed censorship and closed-down hostile newspapers. Mps who had participated in the occupation of the Whitehouse were thrown out of their flats within 3 days of the victory. Western governments ans ST supporters supported Yeltsin’s unconstitutional acts. The parliament leaders were branded as the “Old Guard”. “Yeltsin was faced with the alternative of surrendering to the Old Guard or breaching the constitution” he was reported in the West. This is propagandistic: the parliament had not been asking Yeltsin to surrender; they had been opposing his ST policy. REACTIONS IN CENTRAL/EASTERN EUROPE By the mid-1990s the populations of the region have not only suffered hardships but have elected governments on political platforms that have subsequently been blocked, in Hungary, Poland and Slovakia, by Western pressure. Attempts at ultr-nationalist backlash by the Christian Nationals in Poland, the Republicans in the Czech Republic, the Slovak Nationalist Party or the Csurka breakaway from the MDF in Hungary have all been repudiated by the electorates in the region. In general, the extreme right has been far weaker electorally in Eastern Europe during the 1990s. Instead voters have turned back to the one political current in the region that has received no support whatsoever from the West: the ex-communist socialist parties. These have achieved victories in Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Estonia, Ukraine and have become important also in the former GDR. ROMANIA: A DIFFERENT WAY FORWARD A stark contrast in the policy field would be that between Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic on the one side and Romania on the other. The Romanian case may be taken as a paradigm of an alternative, national, capitalist strategy of transformation counterposed to the ST cycle of “opening to globalism”. The Iliescu regime rejected a sweeping liberalisation of prices, avoided bankruptcies and large lay-offs of workers, sought to maintain the big industrial enterprises and directed its privatisation efforts towards management and worker buy-outs, largely excluding foreign capital. The government was also cautious about liberalising its trade regime. As a result of these policies it was largely rebuffed by the major international economic organisations. Romania initially suffered from acute internal tensions as a result of the form of transition from the Ceaucescu regime. It also suffered from an acute hard-currency shortage. Nevertheless, like Poland, the Romanian economy returned to growth by the end of 1993 with a 1% rise in GDP, and grew by a further 1% the following year. By 1995 it was reported “Romania, little noticed by the West, delivered last year probably the most impressive performance in Eastern Europe”. This does not mean that the Romanian experience should be erected as some sort of superior strategy to that of Poland, for example. Since 1989 the Romanian people have probably suffered more than the Poles. It does suggest 2 possible lines of investigations: 1) Romania had no significant foreign debt and this makes it similar to Poland with its debt reductions; 2) ST opening to global forces is at the very least no panacea if recent growth records are the standard of judgement: Romania has revived far more strongly than wide-open Hungary or the Czech Republic. SOME CONCLUSIONS However it was introduced, capitalism was bound to come as a bit of a shock to the peoples of C/E Euro. Illusions about capitalism were very widespread. Workers did not realise that it would entail a radical drop in their living standards, a great intensification of the work process and chronic insecurity, as well as destitution for a minority. There is a danger of blaming ST for capitalism as such. There were also widespread illusions about what kind of capitalism was on the market from the West. Many East European intellectuals, long disillusioned with dialectices, wanted Swedish-style social-democratic capitalism, not appreciating that if the communist world abandoned state socialism for postwar social-democratic captialism, this very choice would destroy the possibility of realising it: without communism, social democracy would be taken off the menu. It could also be said that official opinion, at least in the Visegrad states, continued, despite mounting popular opposition in Poland and Hungary, to be resolutely committed to the ST course and that this was not only due to Western structural power and pressure. While this is both true and important, it is also important to see why this commitment by these post-communist elites has been so strong. In the Visegrad states the idea of rapid, systematic change has been discursively pakaged as a quick “entry into Europe”. In this form it has been the legitimating discourse for the transformation towards capitalism as such. It has been the way for legitimising privatisation, unemployment, social differentiation and the impoverishment of large sections of the population. Those who have questioned this discourse have been marked as opponents to capitalism as such. Thus to have abandoned the set of Western policies and condition entailed by ST would have required an alternative means of legitmating the social transformation. Yet attempts to hail this country as a success on the basis of current growth tables are a facile way to judge the outcome of ST. The real test is the one proposed by Sachs himself: will ST provide higher living standards than those which prevailed in 1989, as well as democracy and freedom? We do not, of course, yet know! The Economic Dimension of Transition Part II: Attitudes Towards the Market and Government in the Post-Communist States In the aftermath of the anti-communist revolutions of 1989-1991, the new governments in Eastern Europe faced the great task of attempting simultaneously to build market economies and democratic political institutions. Though capitalism and democracy are often considered to be natural allies, in the cases of thesenew states they some-times pull against each other. The costs of the economic transition, in terms of growing unemployment, inequality and inflation, may erode support for the new governments and lead to calls for a “strong government” or leadership to cope with economic dislocations. To a large extent, the success of econmic transitions is dependent on the continuing popularity and legitimacy of new governments. Democratic legitimacy and stability can probably be maintained only if the governments remain broadly responsive to and representative of the opoulations - or at least be perceived as such. Attitudes Towards the Market and Government After the revolutions of 1989 citizens in the post-communist states demonstrated a remarkable ambivalence towards the theory and practice of socialism. The overwhelming majority agreed with the statement that “a free market economy is essential to our economic development. With the revolutions, the countries of C/E Euro left behind systems in whichc state and party dominated the economies and most other aspects of society. The state provided jobs and housing, set prices and wages, owned industries, schools and farms and subsidised basic necessities. The omnipresence and mnipotence of the state aggravated many people and contributed to revolutionary ferver. But many people also came to rely on the benefits provided by the state: under the communist systems, they may not have had freedom or affluence, but they did have basic economic security. The current reforms promise to deliver the former but threaten the latter. Now by the mid-1990s, as the East Euro countries move towards free enterprise and the market, economic inequality will grow sharply as the governments relax restrictions on wages and wealth, and abandon their commitment to full employment. A major task of the new governments is to convince their opoulations to accept greater economic inequality in their societies. This may be difficult given the prevailing attitudes. But in assessing the likely success of market-oriented reforms in the region, it is necessary to consider whi it is that supports and opposses these reforms. It would be helpful for market-oriented governments, of course, if a majority of the population supported the kinds of policies they are implementing. This, however, is not an easy task: many people in the postcommunist states still have a basically egalitarian and statist orientation that works against the laissezfaire and decentralising reforms being implemented. The bad news for the reforming governments has been that opposition to reforms has become mobilised and politically active. Silent majorities could safely be ignored as long as they remained silent. But as the transitional period has become more painful and taken more time, skepticism about the principles of reform has been reinforced by very real economic hardship. The combination of these circumstances has led to opoular upheaval and to electoral defeat for the reforming governments and strong electoral support for the newly revived post-communist parties in Lithuania, Poland and Hungary, and in Russia. RESHAPING CULTURE AND IDEOLOGY This kind of evidence points to some of the social and political obstacles to the transition to market democracies in C/E Euro. It is unlikely that the governments of the region will be able to work against this political culture in the short term: either the governments or the culture will have to change. Given the overwhelming consensus among both the post-communist political elites and Western financial institutions that they should push ahead with reforms, the governments will not lightly change their market-oriented reforms. What they need to do, in that case, is to work on reshaping popular values and political culture. There are those who argue that changes in popular orientations are already beginning to take place and that a shift in favour of the market and capitalism will accelerate as the economic reforms begin to improve the economies and deliver jobs, wealth and consumer goods. Indeed, most of the post-communist states show some shifts away from the radical egalitarianism and hostility to private enterprise that characterised the communist and early post-communist period. As was seen, however, even by 1993, 4 years after the revolutions, attitudes still remained much more egalitarian and statist than in the Western countries. ECONOMIC STATISTICS 1994-95 Basic categories applicable (see notes on 1990-93 in week 6). (Sources: European Bank on Reconstruction and Development - Transition Report (1994).) IMPORTANT: 1) HUNGARY POLAND See figures in Handout week 7 (Shock Therapy) - last page for 1995 figures. Some reform 1968 but especially from 1988 onwards 50% GDP private privatisation especially focussed on small scale 90% + prices free/also trade currency pegged to different international currencies 70% to ECU 30% to Dollar allows for profits accrued to foreign firms to be repatriated Similar except there had initially been reform in 1981 and 1989 some tariffs on trade currency pegged to a “basket” of external currencies CZECH REPUBLIC 60% GDP private comprehesive sale of state assets 85% prices free currency pegged to different currencies 65% Deutsch Mark 35% to Dollar SLOVAK REPUBLIC 50% GDP private same as above 2) BALTIC STATES 50% GDP private privatisation progressing at a steady pace but not as advanced as in above examples prices and trade proportionally well liberated full exchange rate convertibility (Estonia pegged to DM) 3) BULGARIA/ROMANIA Some small-scale liberal reforms in 1987, more in 1990s 35% GDP private prices liberated Bulgarian currency freely convertible Romanian currency pegged to a “basket” ALBANIA 50% GDP private liberalised prices actual privatisation less advanced RUSSIA 1987 perestroika but not real comprehensive econmoic reform, by 1992 fuller moves to economic model along lines of ST 50% GDP private 75% privatisation most prices free trade - organisated predominantly through bilateral relations with CIS ruble floats One major problem - the “shadow economy” CIS Except Kyrgystan - relatively little progress Inflation: Czech Repub: Hungary/Poland/Sovakia: Romania/Bulgaria: Russia: Ukraine: less than 10% p.a less than 35% pa. 51% p.m 51% p.m (previously 13-20%) 10% p.m (previously 40-70%) Growth: Most E. Euro countries and Baltics - increased growth Most CIS states - falling growth, although bottoming-out All countries are probably starting to get growth - see especially this years economic figures Problem in that some are not growing as much as expected Foreign Investment: All E. Euro and CIS countries - experience less foreign direct investment than either China/Mexico These countries have similar levels as Argentina and Malaysia Hungary: Hungary/Czech Repub/Slovak Repub: 44% two-thirds Most aimed at manufacturing industries (Hungary at some service industries) Opportunistic moves in the area by the LARGE foreign firms Some are there to gain access into domestic markets; some there because they see in generally as a way into the regon as a whole (first on the scene). Smaller firms more wary of investing: see it as an unstable region with unstable regimes; some small firms can not afford to take the risk of the high cost of creating new infrstructures. See also the “rouble zone” initiative of 1992-93 for the former Soviet space - initially accepted by CIS, later rejected, all republics now have their own currencies. Trade: Trade between the CIS states is down by 50% Fast reformers in C/E.Euro have been relatively successful in re-orienting trade towards the West, especially the EU European Agreements: Copenhagen Council of EU 1993 Bulgaria/Romania/Czech Repub/Hungary/Poland/Slovakia Enginered towards a progressive and asymmetrical joining with the EU - later full membership EU and Baltics Republics: Free Trade Agreement 1995 Central European Free Trade Agreement 1993: Czech Repub/Slovakia/Hungary/Poland Russian/CIS - rejection of “rouble zone” - replaced by bilateral agreements among the CIS states Bankruptcy Laws - initiated in varying degrees with varying powers of enforcement Divergence: Advanced group has some structural reforms and have stabilised relatively well Intermediate group is progressing at a slower pace but is gradually stabilising Weaker group is still faced with major short- and medium-term problems Reasons for this: 1) geographical position (E vs W) 2) different levels of enthusiasm politically 3) relative degrees of political stability 4) what are the motivations behind Western involvement 5) general uncertainty within the region reflected in Western reluctance 6) structural problems left-over by communist system need to be overcome 7) evaluating the possible outcome is difficult - gradualism vs shock therapy 8) Russian and CIS particular problems separating them from rest of C/E.Euro