The impact of dams on the Mekong in Asia

advertisement

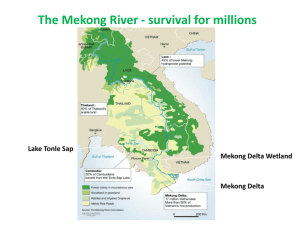

The impact of dams on the Mekong in Asia There are many positive aspects of dams. These include: harnessing of a renewable natural resource lower levels of air and water pollution compared with fossil fuels increasing water flows in the dry season lower flows in the wet season generating electricity to increase industrial output and to raise standards of living. On the other hand, dams may be responsible for many adverse impacts: They alter the volume and timing of water flow. They lead to a decline in water quality. They cause a loss in biodiversity. Fisheries decrease. Sediment is trapped behind the reservoir. People are forced to resettle. They may contribute to seismic activity. Trying to balance the positive and the negative impacts is difficult as not all impacts can be measured in financial terms. Assessing possible trans-boundary impacts is even more difficult. This case study looks at the issues surrounding the Mekong basin in southeast Asia and the six countries through which the Mekong flows – Myanmar (Burma), China, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam (Figure 1). Figure 1. Map of the Mekong basin. Characteristics of the Mekong The Mekong is southeast Asia’s largest river and is a classic example of an international river bearing the brunt of economic conflicts between different countries. It is the world’s eighth largest river in terms of flow, twelfth largest in length and twenty-first in the size of its basin. Whereas most rivers flow in a single direction all year round, the Tonle Sap, a branch of the Mekong that runs through central Cambodia, does not. For half the year, it flows south-easterly towards the South China Sea, but after the summer monsoon, the river reverses its course, and begins flowing towards the northwest into the Tonle Sap lake. Unusually for such a large river in the heart of Asia, the largest city along the Mekong, Phnom Penh in Cambodia, has just 1.1 million inhabitants. Here, the pressure of a burgeoning population and fast economic growth is only just beginning to make its mark on the Mekong. However, the outcome could be all too familiar: a poor compromise between conservation and development. The Mekong River Commission (MRC) was established in 1995 as a river basin management organisation with the task of sharing resources equitably, sustaining the environment and developing resources. Harnessing the Mekong The Mekong is not navigable much beyond Phnom Penh. In the dry season, when the river is low, there are reefs and shifting sandbars. When the water level rises, the many rapids of Si Phan Don, or ‘Four Thousand Islands’, in southern Laos, form an obstacle to shipping. Over a stretch of 30 kilometres, the Mekong divides into a network of streams and channels tumbling over cascades and shoals. The main reason this huge river has always been such an economic backwater is the scanty population along its course. The largest expanse of flat, well-watered and fertile land in the basin lies around Tonle Sap lake, but the devastating annual flood makes intensive agriculture difficult there. Depending on the strength of the rains, the surface area of the lake can swell to up to ten times its normal size during the monsoon. But the water recedes quickly when the rains stop, so the land is alternately flooded and parched. In contrast, the largest countries in the region took shape in more hospitable river basins: China on the Yangtze and Hwang He rivers, Thailand on the Chao Phraya, Vietnam on the Red, and Myanmar (Burma) on the Irrawaddy. There have been numerous attempts in recent decades to harness the Mekong. In the 1950s and 1960s, the USA expressed interest in harnessing the Mekong to enrich Indochina, as well as dent support for the region’s communist supporters. Plans were drawn up to dam the Mekong, and engineers got as far as surveying several sites before the Vietnam War put an end to such schemes. The Mekong remained almost untouched until the 1990s. The first dam on the river, at Man Wan, in China, was not completed until 1993. The first bridge across the lower Mekong (i.e. outside China) was built in 1994, between Vientiane in Laos and Nong Khai in Thailand. The population of Cambodia is growing by almost 2 per cent a year, and along with that of Laos (2.4 per cent) are among the highest rates in Asia. Growth is lower in the Thai and Vietnamese parts of the basin, but they have long been more densely populated. Economic growth is even faster: 4 per cent in 2005 in Thailand and Cambodia, 7–9 per cent in China, Laos and Vietnam (Figure 2). Figure 2. Population growth and economic growth in the Mekong region, 2005. Dams and development To accelerate economic development, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) is promoting schemes to integrate the economies of the ‘greater Mekong sub-region’. Two north–south highways are under construction to link China and Thailand, one via Laos and the other via Myanmar; so are five east–west routes linking Thailand and Vietnam, three via Laos and two via Cambodia. According to the International Rivers Network, an anti-dam group, some 100 large dams are proposed for the Mekong basin. China has already completed two on the Mekong itself, has started work on a third, and plans at least four more. Now that the first two dams have been built and are operating, it is possible to see some of the downstream changes. The river’s flow has changed, sediment has been trapped behind the dam, affecting levels of sediment deposited downstream at Pakse in Laos. The next two dams, Xiaowan and Nuozhadu will have much larger reservoirs and their impacts on the environment and the economy may be even greater. When the Mekong enters Vietnam, it has already formed a delta, leaving no opportunity for dam-building, so the government is building five dams on the one big tributary river that strays across its mountainous border with Cambodia instead. Thailand too has dammed the main tributaries that flow across its territory. The biggest dam enthusiast of all is Laos, which hopes to enrich itself by building enough hydropower projects to become the battery of southeast Asia. Hydroelectric power (HEP) development on the Mekong The potential of the Mekong and its tributaries for hydroelectric power (HEP) is considerable and largely untapped. Early plans to develop the river failed to materialise due to war and civil unrest. So far only 5 per cent (1,600 megawatts) of the lower basin’s hydroelectric potential of approximately 30,000 megawatts have been developed and these few projects have all been on the tributaries (Figure 3). Figure 3. Completed hydroelectric power stations on the Mekong. Of the total potential of 30,000 megawatts in the lower Mekong basin (LMB) approximately 13,000 are on the Mekong, the rest on its tributaries. There is a 13,000 megawatts potential in Laos, 2,200 megawatts on tributaries in Cambodia and 2,000 megawatts potential on tributaries in Vietnam. In contrast, in the upper Mekong basin in Yunnan Province, China there are 23,000 megawatts potential (Figure 4). Figure 4 – List of planned and completed hydropower schemes on the Mekong in China. The demand for electric power in the Mekong basin will increase by an average of 7 per cent annually until 2022. To meet such demand current electric generating capacity will need to quadruple by then. Most of the power generation projects currently planned for Vietnam and Thailand are powered by either coal or natural gas. Some HEP projects are planned on tributary rivers in Laos and Vietnam. There are no plans to dam the main Mekong channel in the LMB for a number of reasons: HEP schemes generally require high initial investment and a long payback period. Most of the potential HEP in the LMB is in Laos or Cambodia but these countries do not have a large home market to warrant large-scale projects. In the long-term, an integrated regional power network would allow Cambodia and Laos to sell power to neighbouring countries with greater need for power. All the other countries which share the Mekong have ambitious plans to engineer their own lengths of river. The governments, mostly without any other major resources, have been keen to back river developments in their own countries, believing that they can export the electricity generated to growing industrial centres in China and Thailand. Social and ecological impact of dam development In 2003 the Asian Development Bank, working with the Norwegian hydropower company Norconsult, recommended a $43 billion (£23 billion) electricity generation and transmission system for the region, which included major dams in Laos, China, Myanmar and Cambodia. Impact on fisheries These dams generate valuable electricity, aid irrigation and regulate flooding. However, in the process they have caused irreparable damage to what was the Mekong's most valuable resource – its fisheries. The Mekong and its tributaries yield more fish than any other river system. The annual harvest, including fish farms, amounts to about 2 million tonnes, or roughly twice the yearly catch from the North Sea. The Mekong is rich in biodiversity. It is home to over 1,200 different species of fish, more than any other river after the Amazon and the Congo. Over 1 million people in Cambodia depend solely on fishing to make a living, while in Laos 70 per cent of rural households supplement their income by fishing. The abundance of fish stems from the Mekong’s seasonal ebb and flow. During the monsoon, the habitat for fish suddenly increases by as much as ten times. Moreover, much of the floodplain is actually forest, which provides leaves for the fish to feed on. They spawn at the end of the dry season, so that the coming floods can carry the fry to the floodplain. The bigger the flood, the greater the feast on offer, and so the fatter and more numerous are the fish. More dams, however, mean smaller floods. Most hydroelectric plants aim to generate the same amount of energy all year round. That requires a consistent flow through the turbines, which in turn requires rainwater to be held in a reservoir for use in the dry season. The same drawback applies to dams designed for flood control. Dams for irrigation, meanwhile, have a doubly damaging impact on fisheries: they not only hold back water, but also encourage the conversion of forest to farmland in the floodplain. Fishermen all along the Mekong are already complaining of falling catches. For now, the problem stems more from the growing number of fishermen than from falling numbers of fish. Fish catch actually doubled in Cambodia between the 1940s and the 1990s. But over the same period, the number of fishermen (along with the population as a whole) has more than tripled. In general, the Mekong is studied so little that the effects of any development project are hard to predict. China, for example, is paying for a scheme that involves blowing up reefs in Laos, Myanmar and Thailand to provide a navigable channel for ships of up to 150 tonnes. Halfway through the blasting, the Thai government suspended the project for fear that the faster flow of an unimpeded current would increase erosion and thus alter the midstream boundary with Laos. Fishermen also worry that, since the reefs may be prime breeding grounds for fish, including the giant catfish, the catch of all species will plummet if their habitat is destroyed. In 1994 Thailand completed a hydropower dam on the Mun river, a major tributary of the Mekong. Since then, the fish catch directly upstream has declined by 60–80 per cent. To avoid a similar fiasco, the World Bank is insisting on several studies and safeguards for the Nam Theun II, a big dam it is financing on a tributary of the Mekong in Laos. However, authoritarian rulers in China, Myanmar and Vietnam do not always investigate big projects so carefully, and little cost—benefit analysis is made of the thousands of small dams, irrigation schemes and land clearances that are undertaken each year throughout the basin. Governments in upstream countries rarely give much thought to the impact of projects on lowly fishermen or farmers beyond their borders in pursuit of bigger economic interests. The Manwan hydroelectric dam across the upper Mekong, finished in 1996, has been frequently blamed by Thailand and other countries for reduced fishing and also for causing flash floods when water is released unpredictably. A second giant dam, at Dachaoshan, is almost complete but is said to be already affecting the river flow, and a third is due for completion in 2012. None of these projects, say the countries downstream, has been fully assessed for its social or ecological impacts outside China, which hopes to generate the equivalent in clean electricity of fifteen major power stations from the first three dams. Irrigation Irrigated rice farming, which is two or three times more productive than the rain-fed sort, is growing rapidly throughout the basin, albeit from a low base. In Laos alone, the area under irrigation increased eightfold in the 1990s. Flood levels have fallen by almost 11 per cent since 1965 (Figure 5). Figure 5. Many subsistence farmers may be forced to leave their lands following flooding by dams. Navigation By 2003–04, previously unseen sandbanks developed in the river’s lower stretches, making navigation increasingly hazardous. The Mekong’s downstream countries, which are almost completely dependent on the river and its tributaries for food, water and transport, fear that China’s plans for further dam building on the river could be disastrous (Figure 6). Figure 6. Dams may improve navigation. Not only was the Mekong’s river flow the lowest in history in 2004, it was also fluctuating as a result of dam operations in China according to the southeast Asia Rivers Network. Low rainfall in 2003 was partly to blame for the river levels, as was increased use of water by growing populations along the whole length of the river, but Chinese dam-building in the upper stretches of the Mekong is thought to be responsible for many of devastating consequences downstream (Figure 7). Figure 7. Dams may allow the extension of farming. Impact on Laos A series of relatively small dams and diversions has already forced the relocation of thousands of indigenous peoples to sites where there is insufficient land or water. Severe fishery declines have been recorded by many villages. In April 2005 the World Bank agreed to lend the government of Laos $270 million to build a dam on the Nam Theun river, a tributary of the Mekong. The Asian Development Bank followed with a loan of $120 million. The dam may impoverish up to 120,000 people, displace 5,700 people and saddle the country with enormous debts. The World Bank, which has been forced to pull out of many large dam schemes in the past because of the social effects involved, says the dam will aid development. However, all the electricity generated is expected to go to Thailand, whose state-owned power company has already signed an agreement to buy most of the electricity generated by the dam. That should bring Laos’s cash-strapped government, which currently depends on foreign aid to fund its budget deficit, up to $2 billion over the dam’s first 25 years of operation. Much of that money, in turn, could be used to fund additional development schemes for ordinary Laotians. The World Bank claims to have learned the lessons of equally worthy-sounding schemes that went badly wrong, including a dam on the Mun river in neighbouring Thailand, which left many fishermen destitute as their catch disappeared. The developers are setting aside money to resettle displaced villagers in Laos, restock the two affected rivers with fish, and manage a new wildlife reserve no less than nine times bigger than the area to be flooded by the dam. The government has also agreed to channel much of its revenue from the dam towards health, education and rural development. But Laos’s communist regime will still be managing the money, policing the wildlife reserve and implementing any schemes to improve the lot of local people – not the sort of tasks at which it has excelled in the past. Impact on Cambodia The cumulative impacts of the Mekong dams are likely to deeply affect Cambodia, where the river’s annual floods create the world’s fourth largest catch of freshwater fish and work for 1.5 million people. Cambodia catches 400,000 tonnes of freshwater fish every year, ranking only behind China, India, and Bangladesh, but annual river levels are thought to have dropped by at least 12 per cent since the dams and irrigation works started upstream. Ecologists fear that the situation could worsen rapidly if the proposed $4 billion Sambor dam is built. This is expected to flood more than 300 square miles, displacing 60,000 people and affecting fishing. Meanwhile dams built by Vietnam on the Se San river, a major Mekong tributary, have been particularly damaging in Cambodia. Se San fishers have complained that there are fewer fish and that the river’s erratic flows often wash away their nets. The fish cannot spawn when it is dry. Conclusion This case study is a good example of the economics versus environment debate, and of centralised government planning versus localised needs. Despite the many examples of large-scale water development schemes which have led to negative results, the countries of the Mekong appear to be doing their best to develop the river’s potential without considering all of the impacts they may cause. About 80 per cent of rice production in the lower Mekong basin depends on water, silt and nutrients provided by the flooding of the Mekong. The Mekong also supports very rich fishing grounds. Dams on the upper Mekong affect water flow in the lower Mekong during the dry season, changing the natural cycle of the river. The dams could mean less frequent floods, adversely affecting farming and fishing. There appears to be little official concern for the remote communities who are most affected by the dams. The Mekong River Commission argues that more needs to be done to protect the environmental and economic interests of it members, and it particularly needs China’s co-operation with this.