LSU Emergency Animal Shelter Disaster Response Manual

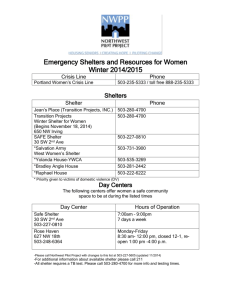

advertisement