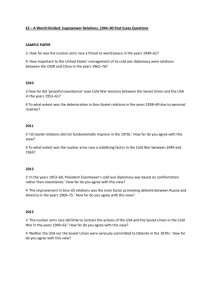

Detente reasons - YR12ModernHIstoryMGHS

advertisement

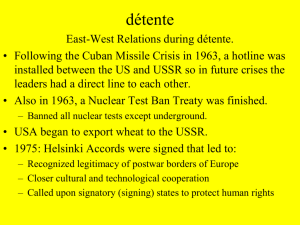

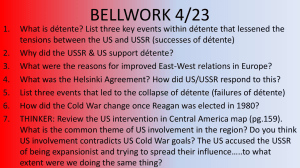

Account for the reasons of détente For the USA and USSR, natural adversaries of the Cold War, the notion of easing tensions through Détente presented a multitude of economic and political benefits. Both saw a move away from the financially demanding arms race as a step that would allow them to refocus the economy on issues that demanded attention after being given secondary importance throughout earlier decades, like trade and domestic concerns. Political failures like Vietnam and the Cuban Missile Crisis simultaneously revealed the inefficiencies of the ideological warfare. These economic and political factors worked in conjunction to propel the move towards peace and détente in the late 1960s. Support for détente from both superpowers grew with the knowledge that it would bring about an easing of the financially debilitating arms race. They were also keen on restraining the race as a result of the development of rough nuclear parity. For the USA and USSR, continuation of the fierce rivalry would only increase the likelihood of their opposition gaining an upper hand. Historian Walter LeFeber reiterates this argument saying that the Americans thought détente would ensure the suppression of the USSR as an even greater threat in an age of nuclear parity. Both powers begun to realise the financially unsustainable nature of the race, as it significantly damaged respective economies. Although military growth did not cease completely, the superpowers agreed on slowing down the arms race, and in consequence there was a natural progression towards peace in the form of détente. The superpowers knew that this move towards détente and concurrent move away from the arms race would correct the damages their rivalry had inflicted upon respective economies and societies. With estimates of ten to twenty percent of each economy focused on military advances, there was a neglect of other significant sectors of the societies. Subsequent protests against the war in the US around the late 1960s pushed the government to adopt a peaceful approach. In the USSR, grain output was being inhibited and the lack of government support resulted in an increase in the frequency of revolts and strikes. For both Nixon and Brezhnev, the notion of peace would invite greater popularity domestically. Brezhnev also assumed that an atmosphere of peace would be the best to promote Communism, which had previously been built on the foundations of a coercive apparatus. The inefficiencies of this system were evidenced by the events of the Czechoslovakian crisis in 1968. Thus for both powers, the economic and social pressures created by the excessive focus on the superpower rivalry indicated the need to partially ease it and initiate a move towards détente. With the damage to their economies through the arms race and superpower rivalry as stated, the USA and USSR understood the significance of initiating peace and détente to help improve trade. For the Soviet, trade with the US would restore the stagnation of the economy that had been initiated by the excessive focus on nuclear arms growth. They needed to keep pace with the rival Western economies and Brezhnev understood the need to increase the capital production through trade. This would improve the growth of agriculture and industry and in turn improve living standards of the USSR. For the US, trade with the USSR would help re-establish the post-WWII era of economic prosperity, which in the late 60s was coming to a close. Thus the prospect of economic co-operation appealed to the governments of both superpowers, furthering the move towards détente. Of momentous significance to the development of détente, were the events of the Cuban Missile Crisis that would reveal to both superpowers the flaws of the ideological warfare between them and the need to reconsider strategy. They realised that a potentially fatal outcome of the nuclear rivalry was very possible and were deterred by the impending dangers of a solution of such nature. Subsequently, improved communication and relations was promoted to avoid the two countries again reaching a point so close to the brink of nuclear destruction. Leaders Khrushchev and Kennedy created a “hot line” between the two nations that would improve communication and was symbolic of the improvement of relations. The imposition of the Partial Test Ban Treaty that restricted nuclear testing in the atmosphere was indicative of the peaceful approach the superpowers now adopted. The atmosphere of fear that was created as a result of the crisis and concern for the possibility of a potential repeat, warranted the move towards détente The USSR was urged towards détente as a result of the exposure of their own vulnerability through the Sino-Soviet split. The breakdown of the relationship between the Soviet Union and China was simultaneous to the gradual improvement of relations between the USA and China. This in turn created the progression of the world from bipolar to multi-polar and it ensured that the USA now had the upper hand. The USSR’s threat deteriorated with the Sino-Soviet split and they were compelled towards peace through détente. This led to an increased understanding of the true nature of the Communist world, and the dismissal of the notion of “Soviet Communist Expansionism” that had earlier been introduced in US Cold War propaganda. The threat of the USSR thus diminished as it was revealed that they didn’t hold a superior hand in the affairs of the Communist world. For the US, their development of financial and political links with China, primarily through trade led to an improvement in their perceptions of Communism and the atmosphere of fierce antagonism was somewhat calmed. Détente was further encouraged by the USA as a result of their damaging experiences in Vietnam, which had the effect of altering the country’s stance on foreign affairs. As can be seen in the geopolitical development of the Sino-Soviet split, Asia played a significant role in the events of the Cold War. The USA’s unsuccessful efforts in Asia developed into a setback in the overall Cold War as it pushed them into considering the idea of peaceful relations with their adversaries. Here, the US was forced to abandon their policy of containment, which had initially set the foundations of the entire Cold War. Unlike in Cuba, where there were only hypothetical scenarios presented, in Vietnam, the USA had actually physically experienced the damaging implications of their attempts to contain the Communist sphere of influence. This was an experience, which would trigger the move towards détente for America, after the Cuban Crisis had earlier “sown the seeds”. Thus the Vietnam War had the effect of forcing the USA to desert their commitment of opposing the “Domino Effect” and take a more peaceful approach to relations with Communism and the Soviets. A multiplicity of motives for peace presented themselves to both superpowers in the lead up to détente. Geopolitical developments, inefficiencies of a wasteful rivalry and the desires for improved trade would eventually diminish the fierce tension that manifested the relationship between the world’s superpowers.