Lecture Notes (with diagrams)

advertisement

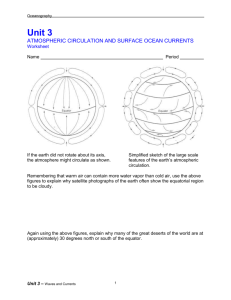

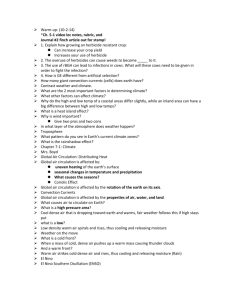

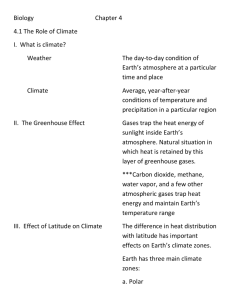

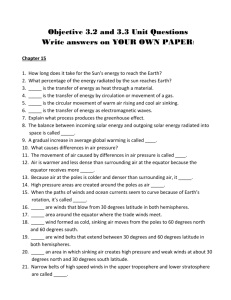

Earth-Sun Relationship The earth rotates counterclockwise (as viewed from above the northern pole) while it revolves around the sun. Because the earth is spherical, the intensity of sunlight is highest at the equator and lowest at the poles. This is visualized when the earth is neither tilted into or away from the sun. These times are called equinoxes, when day and night are equal length. This causes warming of the air at the equator and relative cooling air in the polar regions. This sets up a circulation “pump” – warm air rising around the equator, cold air falling on the poles. This circulation is “sheared” into three sections in each (northern and southern) hemispheres. (See circulation chart below). Because the axis of rotation of the earth is tilted 23.5 degrees off of perpendicular to the plane of revolution, the sunlight distribution on the earth varies throughout the year. This is the cause of seasonal variation in most all biotic communities. But, in general the tropical regions (that part between 23.5 degrees N and 23.5 degrees S latitude) receive the largest amount of energy input. The rising, warm, moist air around the equator, rises, cools, drops water and moves toward the poles. The cooler air descends at the poles. As it descends, it warms, and can hold more water. Because of this, the polar regions are extremely dry. They are very cold because of the low energy input from the sun. The circulation of the atmosphere is "broken" into three "cells" in each hemisphere. See figure on next page. This results in the following patterns: 1) A band of wet, warm, ascending air creates rainy weather near the equator (the equatorial low). 2) A band of dry, warm, descending air around 30 degrees north and south latitude (subtropical high) 3) A band of wet, cool, ascending air around 60 degrees north and south latitude (polar front) 4) A downspout of cold, dry, descending air over both the north and south poles (polar cap). The hot, wet zone is occupied on land with tropical forests. (between 23.5 north and south latitude) The warm, dry zone is the home of the world's biggest deserts. (around 30 degrees north and south) The cool, wet zone is the home the northern confierous forests. (around 60 degrees north and south) The cold, dry zone is the home of the tundra (a low-shrub flatland) and the polar ice caps. The winds of the world relate to this system. In the above diagram the important, global winds are named. The Trade Winds were very important during the sailing days. The "Westerlies" are the major source of our weather in California. Soon, by the end of October, the northern hemisphere polar front will slip south and, hopefully, "open the door" for the march of the winter storms into Northern California. Examine the biome map and convince yourself that this model of global water and air circulation goes a long way in explaining the general distribution of the biomes. It is easily seen in the distribution of the tropical rainforest, the deserts, and the temperate forests (both the deciduous forests and the taiga). Of course, their actual distribution is also modified by ocean currents, wind patterns and topography (mountains, etc.) ================================================================================= Instead of “just memorizing” this, try to recreate the global pattern with the following facts: 1) warm air rises, cold air descends 2) warm air can “hold” more moisture than cold air. (condensation often occurs when air is cooled). 3) The sun pumps more energy into the tropics than toward the poles. 4) This “pump” sets up the basic (theoretical) circulation. 5) The rotation of the earth splits the basic hemispherical circulation into 3 parts (for each hemisphere). 6) This shearing causes – the tropics to be wet, the “horse latitudes” (at 30 degrees N and S) to be dry, the “polar fronts” (at 60 degrees N and S) to be wet and the poles themselves (at 90 degrees) to be dry. 7) Combining 6) above with the heat distribution gives us the basic model. Ocean currents flow in predictable ways as well, but in this brief survey we are not going to “dive” into them! However, I would expect you to know: 1) The Japan-California current. Flows in a clockwise direction in the Northern Pacific, bringing cold water down the coast of California. This influences our climate (long-term) and weather (short-term) patterns significantly. 2) The “Gulf Stream” that flows in a clockwise direction in the N. Atlantic. It brings relatively warm water up the east coast (part of the reason for hot, humid summers) and bathes Northern Europe in warmish water. 3) The “Humboldt Current” that flows counter-clockwise in the S. Pacific, bringing cold water up the coast of Peru (hence the deserts on that coast), flows westward and then bathes Indonesia (and N. Australia) with warm water. This global circulation of air and water model is a very strong predictor of biome distribution worldwide and explains patterns on the earth that are truly puzzling without it.