Written Comments of The Open Society Justice

advertisement

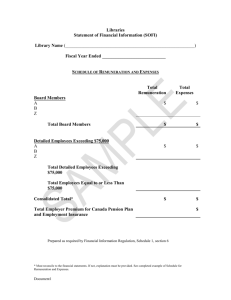

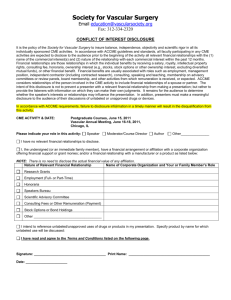

WRITTEN COMMENTS OF THE OPEN SOCIETY JUSTICE INITIATIVE on the Consejo para La Transparencia’s Draft Regulations Regarding Disclosure of Remuneration for Public Companies and State Owned / Controlled Companies I. Introduction and Statement of Interest The Open Society Justice Initiative provides this submission to assist the Consejo para la Transparencia (hereafter “Consejo”) in developing regulations concerning the disclosure of remuneration for Executives and Directors of public companies and state-owned or state– controlled companies (the “Regulations”). The Justice Initiative, a worldwide legal program of the Open Society Institute, pursues law reform activities grounded in the protection of human rights, and contributes to the development of legal capacity for open societies. The Justice Initiative combines litigation, legal advocacy, technical assistance, and the dissemination of knowledge to secure advances in four priority areas: national criminal justice, international justice, freedom of information and expression, equality and citizenship, and anti-corruption. Its offices are in Budapest (Hungary), New York (United States) and Abuja (Nigeria). In the area of access to information, the Justice Initiative has extensive experience in promoting the adoption and implementation of freedom of information laws in Eastern Europe, Latin America, and elsewhere. It has also contributed to international standard-setting and monitoring of government transparency around the world. The Justice Initiative files amicus curiae briefs with national and international courts and tribunals on significant questions of law where its thematically focused expertise may be of assistance. In the area of freedom of expression and information, the Justice Initiative has provided pro bono representation before, or filed amicus briefs with, all three regional human rights systems and the UN Human Rights Committee. In particular, the Justice Initiative, jointly with four other groups, filed amicus curiae briefs with both the Inter-American Commission and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in the landmark case of Claude Reyes et al v. Chile. The Regulations proposed by the Consejo require public companies and state owned or controlled companies (collectively referred to herein as “SOEs”) to publicly disclose several categories of information including (i) constitutive documents and the legal framework applicable to such companies, (ii) organizational structure, (iii) financial conditions, (iv) related companies, and (v) the directors and management group. Our comments address only those portions of the Regulations related to the disclosure of remuneration practices of Chilean companies. Substantial attention has been devoted in recent years to the regulation of executive remuneration. Our research indicates that the clear international trend is to require disclosure of remuneration paid to officials, both of companies that are not affiliated with the state but which are publicly traded on a national stock exchange as well as SOEs.1 1 We understand that the Regulations would apply only to public companies created by law, companies of the state and companies in which the state has a 50% or more ownership stake or the majority of the board. Although these 1 Section II of these Comments sets forth seven arguments that have been advanced to justify and advocate for robust disclosure requirements by numerous experts, including experts on practices in China, Switzerland, Australia, the U.S., U.K., EU and OECD. Section III summarizes the disclosure requirements found in various developed and developing countries. Section IV concludes that the disclosure regulations promulgated by the Consejo are consistent with policies and principles underlying democratic institutions, transparency, democracy and good corporate governance, and offers some additional recommendations that the Consejo may wish to take into account as it continues to elaborate and apply guidelines regarding disclosure requirements for Chilean companies. II. Policy Justifications for the Proposed Regulations Disclosure requirements serve several important functions in ensuring transparency and openness in corporate governance. This Section provides an overview of these functions. a. Requiring disclosure of remuneration makes directors and executives more accountable to shareholders and the public at large. Where remuneration is set by an agent (such as a board of directors), there must be a certain level of accountability in order to prevent self-dealing among the board and the executives. The disclosure regime proposed in the Regulations increases this accountability.2 The board must “certify” (through disclosure) that the remuneration is reasonable and promotes shareholder interests. Disclosure causes the board to justify its pay choices publicly and with more care.3 If the shareholders do not believe that the board is fulfilling its duties with respect to remuneration, they can dismiss directors that are not acting in the corporation’s best interests or adopt new corporate resolutions that prevent such abuses.4 The act of disclosing compensation allows shareholders to act as corporate monitors and keeps the behavior of those in charge of compensation in check by exposing any potential self-dealing or corporate waste in the form of unjustified compensation packages.5 Comments do in part draw from examples of disclosure regimes and scholarly work that is focused on non-state affiliated, publicly traded companies, we believe, for the reasons stated herein, that the justifications for requiring disclosure of remuneration practices is equally forceful in the case of SOEs. 2 Jennifer G. Hill, (Professor, University of Sydney Law School), What Reward Have Ye? Disclosure of Director and Executive Remuneration in Australia, 14 CO. SEC. L. J. (1996) at 13, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=934697. Please note that all references cited herein are on file with Ropes & Gray. 3 Guido A. Ferrarini (Professor, University of Genoa), Niamh Moloney (Professor, London School of Economics) & Cristina Vespro (Université Libre de Bruxelles), Executive Remuneration in the EU: Comparative Law and Practice, 14 (ECGI, Working Paper No. 09/2003), available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=419120; see also Hill, supra note 2, at 13. 4 See Hill, supra note 2, at 13. 5 Id. 2 b. Disclosure permits shareholders to effectively monitor management and remuneration practices and reduce costs of the agency relationship between shareholders and executives. In the typical corporate governance structure, the owners of the company (shareholders) do not manage the company’s affairs. The owners rely on hired managers (executives) to run the enterprise for them. This dynamic creates an agency relationship between the shareholders and the executives (agents), which inherently creates a conflict.6 With respect to executive compensation, the interests of the executives (one of which is to maximize their own compensation) are not clearly aligned with those of the shareholders – to maximize the value of the company.7 Shareholders can reduce the conflict by monitoring management to ensure that management does not act in its own self-interest.8 Constantly monitoring management, however, is time consuming and costly, and it is unlikely that any single shareholder will have sufficient incentive to monitor management.9 Shareholders have only a fractional interest in firm profits and are not incentivized individually to monitor and discipline management.10 Even when the information is obtained after such effort, it is in a format that would be hard to compare to other companies in a meaningful fashion. Uniform disclosure of executive and director compensation, as it is proposed in the Regulations, is an effective method of combating this conflict in a way that lowers the shareholders’ monitoring costs.11 As stated by Rashid Bahar, an expert at the University of Geneva: Over the last decade, regulators and promoters of corporate governance codes have increasingly relied on transparency to resolve the conflict of interest in executive compensation. This increased disclosure is implemented by statute, agency regulation, or corporate governance codes. This approach is based on the underlying assumption that if investors are informed of the compensation scheme, they will be again in a position to check and react against managerial excesses. In other words, by forcing companies to disclose information the proponents of this 6 See Rashid Bahar, (Assoc. Professor, Centre de Droit Bancaire et Financier, Université de Genève), Executive Compensation: Is Disclosure Enough?, 3 (Université de Genève, Working Paper, Dec. 9, 2005), available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=869415. 7 See Lucian A. Bebchuk (Professor of Law, Harvard Law School) & Jesse M. Fried (Professor of Law, University of California, Berkeley), Executive Compensation as an Agency Problem. 17 J. ECON. PERSP. 71, 71-92 (2003), available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=364220. 8 See Bahar, supra note 6, at 34. Ferrarini, Moloney & Vespro, supra note 3, at 13 (“Collective action problems are exacerbated in the case of executive pay as shareholders are unlikely to see great individual gains from a reduction to the costs of [executive] pay.”). 9 10 Id. at 5. 11 Edward Iacobucci (Assist. Professor, University of Toronto Faculty of Law), The Effects of Disclosure on Executive Compensation, 48 U. TORONTO L. J. 489, 499-500 (1998). 3 approach hope to lower the costs of monitoring by shareholders and reduce the agency costs linked to executive compensation.12 Greater monitoring of remuneration through mandatory disclosure of executive pay as set forth in the Consejo’s proposed Regulations would strengthen the correlation between executive compensation and firm performance and would reduce the agency costs inherent in this relationship.13 c. The increased transparency resulting from disclosure increases “outrage costs” and is accordingly a strong constraint against managerial abuse. As noted above, because shareholders are often unable to effectively monitor management, directors and executives may be able to extract excessive remuneration packages. Scholars argue that shareholder and public “outrage” can act as a counterbalancing constraint on the power of management to extract such excessive remuneration.14 Such outrage may produce an additional constraint on excessive remuneration packages as directors and management may be unwilling to adopt remuneration arrangements when faced with such a reaction from shareholders and the public. This reaction is referred to as the “outrage cost” that directors and management must weigh against the particular benefits of a remuneration package when considering whether to adopt or approve it. When the cost is sufficiently high, management may find itself unable to justify certain compensation practices because of the reputational damage that might follow or a desire to avoid being perceived as an “outlier” and the potential for negative publicity.15 Evidence in the United States as well as the United Kingdom and Australia suggests that this “outrage cost” can be an effective restraint on managerial power.16 12 Bahar, supra note 6, at 22-3. 13 See Guanghua Yu, (Assoc. Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Hong Kong), The Regulation of Executive Compensation: An Agency Perspective, a paper focusing on the practice in China, including regarding SOEs, presented at the 16th Annual Corporate Law Teachers Association Conference organized by the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia during February 5-7, 2006, available at http://users.austlii.edu.au/clta/docs/pdf/2006-confpapers/yu.pdf. 14 Lucian A. Bebchuk & Jesse M. Fried, PAY WITHOUT PERFORMANCE: THE UNFULFILLED PROMISE OF EXECUTIVE COMPENSATION (Harvard Univ. Press 2004), p 65; see also Lucian A. Bebchuck, Jesse M. Fried and David I. Walker (Professor, Boston University School of Law), Managerial Power and Rent Extraction in the Design of Executive Compensation, 69 U CHI. LAW REV. 751, 786 (2002). 15 Bebchuk, Fried & Walker, supra note 14, at 786-787. 16 See, e.g., Marilyn F. Johnson (Assoc. Professor, Michigan State University), Susan L. Porter (Assist. Professor, University of Texas at Austin), and Margaret B. Shackell-Dowell (Cornell University), Stakeholder Pressure and the Structure of Executive Compensation (Working Paper, May, 1997), available at http://papers.ssrn.com/id=41780 (finding that companies receiving negative coverage of their executive compensation policies in various business publications experienced smaller increases in total compensation than comparable firms in subsequent years); Kym M. Sheehan (Snr. Lecturer, Faculty of Economics & Business, University of Sydney), Is the Outrage Constraint an Effective Constraint on Executive Remuneration? Evidence from the UK and Preliminary Results from Australia, (Working Paper, March 18, 2007), available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=974965 (discussing evidence that disclosure and shareholder ratification requirements in the UK and Australia may lead companies to “make the necessary 4 In order for this “outrage cost” to function effectively, the outrage must be sufficiently widespread “amongst relevant groups of people.” If the outrage is not sufficiently widespread, management will have little or no incentive to take the potential outrage cost into account when considering remuneration packages.17 Relevant groups include investors, media, and social and professional groups about whose views the executives and directors care.18 Accordingly, transparency may enhance this “outrage” cost via a multiplier effect – the greater the required disclosure and the more widely available such disclosure is made, the more likely a greater portion of the public will experience this outrage, thus enhancing the “outrage cost” that may result from approving such compensation packages. d. Disclosure encourages the development of norms regarding remuneration practices. The disclosure requirements in the Regulations will make available to shareholders and the public valuable information that “signals” management’s view of “acceptable and appropriate” remuneration. This signaling and feedback process plays an important role in ensuring that companies adopt remuneration practices that are reasonable and norm-adjusted. As all companies fulfill their disclosure requirements and a greater amount of information becomes available regarding remuneration practices, norms regarding “acceptable and appropriate” remuneration practices may start to develop.19 Companies will then likely find it difficult to stray from these norms without a clear justification for doing so. Mandating disclosure is crucial in ensuring the effective functioning of this process: without such disclosure requirements, interested parties would likely find it impossible to obtain reliable and complete information regarding the remuneration practices of companies. Even if they are able to obtain such information regarding a particular company, it is of limited utility when they are unable to compare it to the practices of other similar companies. e. Requiring disclosure is a cost effective and less intrusive method of controlling compensation than other methods that have been tried. Although some costs will be incurred in preparing information that must be disclosed, the costs of such efforts likely are outweighed by the costs that would result from requiring companies to adopt remuneration practices that comply with some legal or judicial limit.20 Moreover, disclosure will only indirectly impact on remuneration practices of companies thus ensuring that companies efficiently allocate resources. This should be compared to the experiences of other countries that have sought to regulate and limit remuneration through other more costly and intrusive measures. adjustments to remuneration to ensure their remuneration complies with prevailing views of acceptable remuneration.”). 17 Bebchuk, Fried & Walker, supra note 14, at 787. 18 Id. at 788. 19 See Bahar, supra note 6, at 44; see also Hill, supra note 2, at 14. 20 See Hill, supra note 2, at 14. 5 For example, in the United States, provisions in the tax law seek to directly limit remuneration through the denial of tax benefits. These include (i) Section 162(m) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the “Code”), that limits public companies from taking a deduction for remuneration for certain named executives that is in excess of USD $1 million (unless such remuneration qualifies as “performance-based” under detailed rules) and (ii) Code Section 280G, that both denies a company a deduction for and imposes a 20% nondeductible “excise tax” on a recipient of, an “excessive parachute payment” or “golden parachute” payment (very generally defined as a payment that is contingent on a change in control of the company and that exceeds a certain base amount). More recently the United States has enacted detailed and onerous requirements aimed at regulating and limiting the ability of executives to defer the receipt of remuneration. 21 Companies have expended countless resources in designing remuneration packages that are intended to comply with these provisions and it is debatable what effect they have had on remuneration.22 Whether such limitations are an effective way of regulating remuneration or misguided efforts, it remains that disclosure can play an important role in ensuring transparency regarding remuneration practices in a far less intrusive manner and without these potential unintended consequences. f. Requiring disclosure in the case of state owned / controlled enterprises (SOEs) is an important part of ensuring proper corporate governance of such companies. Lack of transparency is one of the largest problems in the corporate governance of SOEs. According to a study conducted by the World Bank, lack of transparency “undermines the ability to monitor management, limits the accountability of management and the government, and can conceal liabilities that can have an impact on national budgets and even financial stability.”23 The study concludes that lack of transparency can limit the ability of a country to attract capital at competitive rates, build efficient and trusted institutions, and maximize its economic growth. 24 Transparency and disclosure prevent the corruption and unchecked management practices that investors fear in SOEs and allow for fairness and the predictability of the rule of law.25 A reason for this lack of transparency is that government and individual officers in these enterprises attempt to promote their own political or individual goals.26 21 See, e.g., 26 U.S.C. §§409A, 457A. 22 See, e.g., John R. Graham (Professor, Duke University) & Yonghan Wu (Barclays Global Investors), Executive Compensation, Interlocked Compensation Committees, and the 162(m) Cap on Tax Deductibility, (Working Paper, January 2007), available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=959686 (concluding that Code Section 162(m) does reduce remuneration); but see Johnson, Porter, & Shackell-Dowell, supra, note 16 (concluding that Code Section 162(m) does not generally result in a reduction of executive remuneration). 23 David Robinett (Corporate Governance Dept., The World Bank), Held by the Invisible Hand: The Challenge of SOE Corporate Governance for Emerging Markets, 19 (May 2006), available at http://rru.worldbank.org/Documents/Other/CorpGovSOEs.pdf. 24 Id. at 19. 25 Id at 15. Standard & Poor’s Governance Services, Transparency and Disclosure by Russian State-Owned Enterprises, 2 (June 2005), available at http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/9/59/35175841.pdf. 26 6 The Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) has published Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises.27 Chapter V, on Transparency and Disclosure, provides that SOEs should be subject to (1) an annual independent external audit based on international standards28 and (2) the same high quality accounting and auditing standards to which listed companies are subject, including the requirement to disclose remuneration policies.29 The Consejo’s proposed Regulations fully comply with the Guidelines proposed by the OECD. Requiring disclosure of remuneration practices is made all the more important in SOEs where the “shareholders” (e.g., taxpayers) are unlikely to be able to exercise the same influence over management as shareholders of a company that is not affiliated with the state. Moreover, unlike in the case of a publicly traded company not affiliated with the state (where shareholders may express their disapproval of remuneration practices and management generally by selling their shares), taxpayers often have limited means for expressing their disagreement with management of SOEs. Therefore, ensuring transparency and the availability of information regarding remuneration practices of SOEs is an important part of ensuring good corporate governance and may also enhance the public’s trust in SOEs. Requiring such disclosure is also justified by the fact that corporations (including state owned/controlled ones) derive benefits by their very status of being corporations. For example, corporations enjoy the benefits of the rule of law (limited liability, etc.) as well as a legal and regulatory framework within which they may operate. With such benefits comes a responsibility to the public, and disclosure is part of the corporate responsibility to the public to control profligacy and self-dealing. Although executives of SOEs may in some sense be “employees” of the state, there are important parallels between their position and those of executives in a non-state affiliated company. Indeed, executives of SOEs generally have all the duties and powers of executives of a non-state affiliated company and more. Directors and executives of SOEs are accountable to the public as they are performing government functions as part of their job. It is reasonable and fair, as part of ensuring this accountability, to inform the public of their remuneration so the public is able to assess for itself whether such remuneration is fair and appropriate. g. The Consejo’s proposed Regulations are consistent with the clear international trend towards requiring disclosure and will be welcome in ensuring the standardization of such disclosure rules. As evidenced by the discussion in Section II below regarding the disclosure requirements in various countries, it is clear that the benefits that disclosure can play in ensuring good corporate governance have become well accepted. The Regulations play an important role in this evolving process – as more countries adopt disclosure requirements, and as countries 27 ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT, OECD GUIDELINES ON CORPORATE GOVERNANCE OF STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISES (2005). 28 Id. 29 Id at 44. 7 continue to develop and perfect these disclosure requirements, disclosure regimes will begin to standardize and coalesce around a “model” approach to disclosure.30 The adoption of such a “model” approach will make it easier to compare remuneration practices across a wider spectrum. III. Disclosure Regimes in Other Countries As noted, the strong international trend is to require disclosure regarding the remuneration of directors and executives of both publicly traded, non-state affiliated companies as well as for SOEs. For instance, the OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance call for the disclosure of compensation to individual board members and key executives,31 termination and retirement provisions,32 and any specific facility or in-kind remuneration provided to management.33 The European Union has for several years been working on a model set of disclosure requirements for companies in the EU.34 This Section provides brief summaries of the disclosure regimes in various countries throughout the world. Although the discussion below focuses in part on disclosure requirements applicable to non-state affiliated, publicly traded companies (and not SOEs), we believe these disclosure requirements are relevant examples in evaluating the Regulations. Indeed, for the reasons noted above, the disclosure requirements applicable to non-state affiliated, publicly traded companies should apply equally to SOEs where the same issues regarding lack of information, agency conflicts and need for development of best practices in the area of remuneration are just as, if not more, acute. a. United States Under rules promulgated by the United States Securities & Exchange Commission (the “SEC”), non-state affiliated, publicly traded companies listed on a national stock exchange in the United States must, on an annual basis, disclose detailed information regarding the remuneration of all directors as well as the Chief Executive Officer, Chief Financial Officer and the three other most highly paid officers.35 The rules generally call for three types of disclosure of executive 30 See Hill, supra note 2, at 17. 31 ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT, OECD PRINCIPLES OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 22 (2004), available at http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/32/18/31557724.pdf. 32 Id. 33 Id at 52. 34 See 2004 O.J. (L 385) 55, 14.12.2004, available at http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2004:385:0055:0059:EN:PDF; see also European Union: European Commission, Report on the Application by Member States of the EU of the Commission Recommendation on Directors’ Remuneration, 13 July 2007, SEC (2007) 1022, available at http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/company/docs/directors-remun/sec20071022_en.pdf; Statement of the European Corporate Governance Forum on Director Remuneration 1 (March 23, 2009), available at http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/company/docs/ecgforum/ecgf-remuneration_en.pdf. The particular rules for disclosure are set forth in the provisions of the SEC’s Regulation S-K, specifically, Item 402 (Executive Compensation), Item 403 (Security Ownership), and Item 404 (Related Party Transactions). 17 C.F.R. §§ 229.402-.404 (2008). 35 8 remuneration paid or earned during the prior year: (1) tabular disclosures regarding executive remuneration36 and director remuneration;37 (2) narrative description of other types of remuneration and any information material to an understanding of the tabular information,38 and (3) a Compensation Discussion and Analysis (“CD&A”).39 All of this information is required to be included in a company’s annual proxy statement, which is made publicly available through the SEC’s website.40 The information required to be included in the tabular disclosures for executives includes information for the three preceding fiscal years regarding yearly salary, bonus remuneration, remuneration in the form of equity awards, and remuneration that is deferred. Tabular disclosures required for directors are similar (although slightly less detailed, particularly with regard to equity remuneration).41 Detailed rules apply in determining the value to be reported for equity remuneration which are beyond the scope of this commentary paper.42 These tabular disclosures must be accompanied by narratives that are to “provide a narrative description of any material factors necessary to an understanding of the information disclosed in the tables.”43 The largest recent change in disclosure requirements for public companies in the United States was the addition of a requirement that a company’s annual proxy statement must include, generally as of December 15, 2006, a CD&A which is to discuss “all material elements of the [company’s remuneration] of the named executive officers.”44 The SEC has indicated that a company must address six items in its CD&A: (i) the objectives of the company’s remuneration programs; (ii) what the remuneration programs of the company are designed to reward; (iii) what is each element of remuneration; (iv) why the company chooses to pay each element of remuneration; (v) how the company determines the amount for each element of remuneration; and (vi) how each element of remuneration and the company’s decisions regarding that element fit into the company’s overall compensation objectives and affect decisions regarding other elements of remuneration.45 36 17 C.F.R. § 229.402(c) (2008) (summary compensation table); 17 C.F.R. § 229.402(d) (2008) (grants of planbased awards table); 17 C.F.R. § 229.402(f) (2008) (outstanding equity awards at fiscal year-end table); 17 C.F.R. § 229.402(g) (2008) (Option exercises and stock vested table); 17 C.F.R. § 229.402(h) (2008) (pension benefits table). 37 17 C.F.R. § 229.402(k) (2008). 38 17 C.F.R. § 229.402(e) (2008). 39 17 C.F.R. § 229.402(b) (2008). 40 See generally http://www.sec.gov. 41 To view a sample summary compensation table for a US company listed on the NASDAQ stock exchange, see http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1288741/000119312509078820/ddef14a.htm at 19. 42 For an excellent summary of the considerations and calculations that companies subject to the disclosure regime should take into account in preparing this tabular disclosure see W. Alan Kailer (Partner at Hunton & Williams), The Securities and Exchange Commission’s 2006 Executive Compensation Rules: Preparing the Executive Compensation Tables, (Hunton & Williams LLP, Dallas, TX) January 2008, available at http://www.utcle.org/eLibrary/preview.php?asset_file_id=14930. 43 17 C.F.R. § 229.402(e)(1) (2008). 44 17 C.F.R. § 229.402(b)(1) (2008). 45 Id. 9 In revising the disclosure rules to require a CD&A, the SEC indicated that the CD&A was “intended to provide investors with a clearer and more complete picture” of remuneration practices of the company and accordingly the CD&A “needs to be focused on how and why a company arrives at specific executive [remuneration] decisions and policies.”46 Thus, the CD&A is an effort to move beyond a tabular presentation of numerical information regarding remuneration and towards a more complete discussion of how remuneration is set at public companies, thereby providing shareholders with more detailed information regarding the process taken by management in setting remuneration for directors and executives. In addition to the above disclosures and the CD&A, other regulations are intended to increase transparency in remuneration practices of public companies and corporate governance generally. For example, disclosure is required regarding (i) beneficial ownership of public company securities by persons owning 5% or more of any class of the company’s voting securities and executives and directors;47 (ii) transactions between the company and related persons (generally defined to include officers, directors, 5% beneficial holders, and close family members of these individuals);48 and (iii) disclosure regarding a company’s processes and procedures for the consideration and determination of executive and director remuneration.49 The United States disclosure regime is one of the most comprehensive disclosure regimes in the world and has served as a model for numerous other countries in developing their own disclosure regimes. As the above summary demonstrates, this disclosure regime places emphasis on both (i) detailed disclosure of “straightforward” remuneration information in a format that readily allows comparison across companies and (ii) disclosure regarding the general remuneration processes and decisions of public companies and corporate governance matters related to remuneration practices. Moreover, recent indications are that the SEC’s emphasis on disclosure is going to increase. Just this year, the SEC has indicated that it is considering expanding disclosure requirements to require enhanced disclosure about the company’s compensation policies and practices, including disclosure for non-executive officers, if such policies have a material impact on the company's risk profile.50 b. Canada The current disclosure regime in Canada is very similar to that of the United States, an unsurprising fact when one considers that many Canadian companies are subject to the disclosure rules in the United States by virtue of being listed on stock exchanges in the United 46 Staff Observations in the Review of Executive Compensation Disclosure, Division of Corporate Finance, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, September 10, 2007, available at http://www.sec.gov/divisions/corpfin/guidance/execcompdisclosure.htm. 47 17 C.F.R. § 229.403 (2008). 48 17 C.F.R. § 229.404 (2008). 49 17 C.F.R. § 229.407 (2008). See SEC’s Proposed Rule: Proxy Disclosure and Solicitation Enhancements, available at http://www.sec.gov/rules/proposed/2009/33-9052.pdf; see also, SEC Acts on Proxy Disclosure and Voting Issues, ROPES & GRAY CLIENT ALERT (Ropes & Gray LLP, Boston, MA), July 6, 2009, available at http://www.ropesgray.com/secactsproxydisclosurevotingissues/. 50 10 States. Although certain differences exist in the exact information that must be disclosed and how information must be presented, the required disclosure is generally as robust as in the United States.51 Thus, under rules promulgated by the Canadian Securities Administrators (“CSA”), non-state affiliated, publicly traded companies listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange must include in annual filings summaries of remuneration for the CEO, Chief Financial Officer and the three next most highly compensated officers and for all directors as well as a “Compensation Discussion & Analysis” which is very similar to the CD&A required for U.S. public companies discussed above. This information is publicly available through the CSA’s online database.52 c. Europe In October 2004, the EU Commission recommended that publicly traded companies disclose their policies on executive remuneration, as well as the levels and form of each individual executive’s pay.53 The EU Commission recommendations are not legally binding, and accordingly there exists a range of mandatory disclosure regimes in Europe. At one end of the spectrum are the UK, Ireland and France, which have mandatory disclosure regimes that are similar to those in the US (e.g. individual level reporting). Other countries such as Portugal and Denmark only require aggregate reporting with limited breakdown of individual amounts.54 Exhibit A contains an illustrative table of the different disclosure regimes in the larger European economies and includes how the Consejo’s proposed Regulations compare to these disclosure rules.55 Below is a brief description of the disclosure regimes in the United Kingdom (the country with the most disclosure in Europe) and Germany (the country with the most similar disclosure regime to Chile in Western Europe). i. United Kingdom 51 For comparisons of the disclosure regimes in the United States and Canada see Proposed New Canadian Executive Compensation Disclosure Rules Released, UPDATE (Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP, Toronto, Ontario, Canada), May 11, 2007, available at http://www.osler.com/uploadedFiles/Resources/Publications/12098Updated%20Sept%204Proposed%20New%20Canadian%20Executive%20Compensation%20Disclosure%20Rules%20Released.pdf ; and DELOITTE & TOUCHE LLP, ENHANCED DISCLOSURE OF EXECUTIVE COMPENSATION: THE DELOITTE PERSPECTIVE (2007), available at http://www.deloitte.com/dtt/cda/doc/content//ca_en_ExecutiveCompensation_may07.pdf. 52 CSA’s online database can be found at http://www.sedar.com/. Western European Executive Pay Disclosure Trends Bode Well for Better Credit Analysis, MOODY’S GLOBAL CORPORATE GOVERNANCE: SPECIAL COMMENT 5 (Moody’s Investors Service, New York, NY), December 2007, available at http://v3.moodys.com/sites/products/AboutMoodysRatingsAttachments/2007000000459228.pdf. 53 54 See generally: Velma Roberts et al., Executive Compensation Disclosure in Europe, PERSPECTIVE (Mercer Limited, London, England), Sept. 25, 2007, available at http://www.mercer.com/referencecontent.htm?idContent=1282000 (follow “Download Perspective” hyperlink) [hereinafter Mercer Report]; Guido Ferrarini, A European Perspective on Executive Remuneration (September 2008) (unpublished presentation), available at http://www.ecgi.org/remuneration/documents/ferrarini_presentation.pdf; and Ferrarini, Moloney & Vespro, supra note 3. 55 See Mercer Report at 3. The table is included as Exhibit A to compare the proposed Chilean disclosure regime to the European disclosure regime that existed less than two years ago. 11 The United Kingdom has the most extensive set of disclosure requirements with respect to management compensation in Europe. Under the Companies Act 2006 and the UK Listing Rules, the UK requires publicly traded companies listed on a national stock exchange to disclose executive compensation in their annual reports. The disclosure regime requires the disclosure of salary, fees, bonus benefits, pension and long term incentives in a tabular format.56 In addition, companies are required to provide a detailed description of several compensation elements including: executive compensation philosophy, overview of bonuses, overview of long term incentive plans, description of pensions, payouts to departing executives, and the peer groups used to help determine remuneration.57 Most notably, the United Kingdom requires a vote of the shareholders to approve the remuneration report.58 This is a level of disclosure that is not prevalent in the rest of the world but has been cited as “best practices” for listed companies in Europe.59 ii. Germany In Germany, the Corporate Governance Code, as amended on June 18, 2008, requires the disclosure of compensation of directors of German listed companies. 60 Mandatory executive compensation disclosure rules are contained in the German Commercial Code and require that the notes to the annual balance sheet and profit and loss statement of medium-sized and large corporations report the total remuneration of members of the company’s leadership.61 Remuneration that must be disclosed includes salaries, profit participations, options and other share-based payments, expense allowances, insurance payments, commissions and fringe benefits of every kind.62 German disclosure requirements do not, however, require the qualitative description of the compensation.63 For instance, the philosophy behind the executive compensation and the explanations of the bonuses are typically not provided in all annual reports. One aspect in which the disclosure regime in Germany diverges from the Consejo’s proposed Regulations is that in Germany the shareholders are allowed a non-binding vote on the remuneration report.64 d. Brazil 56 Jonathan Baird (Partner at Altheimer & Gray) & Peter Stowasser (Partner at Schulte Rechtsanwälte), Executive Compensation Disclosure Requirements: The German, UK and US Approaches, GLOBAL COUNSEL (Practical Law Company, London, England) 29, 33 (October 2002), available at http://crossborder.practicallaw.com/4-101-7960 (follow “Download PDF” hyperlink). 57 Mercer Report at 3. 58 Id. 59 See Ferrarini, supra note 54; see also Moody’s supra note 53 at 5. 60 Handelsgesetzbuch [HGB] [Commercial Code] June 18, 2009, BGBl. I, available at http://www.corporategovernance-code.de/eng/download/E_CorGov_Final_Version_June_2009.pdf. 61 Baird & Stowasser, supra note 56, at 30 62 Id. 63 Mercer Report at 3. 64 Id. 12 In Brazil, the city of São Paulo has shown leadership in disclosing the salaries of public officials and officials of public companies. Although under no legal obligation to do so, the City Hall of São Paulo has been publishing the salaries of public officials and officials of public companies since June 2008.65 Publishing the salaries was a response to a municipal law (Lei n 14.720/2008)66 which requires information – including the name, the position and the unit where the official works – to be published on the web. A decree signed by the Mayor implements the above mentioned law.67 As for public companies, they are mentioned in the Constitution68 and are defined in the decree as well. According to the decree: “II - Emprêsa Pública - a entidade dotada de personalidade jurídica de direito privado, com patrimônio próprio e capital exclusivo da União, criado por lei para a exploração de atividade econômica que o Govêrno seja levado a exercer por fôrça de contingência ou de conveniência administrativa podendo revestir-se de qualquer das formas admitidas em direito.”69 On June 16, 2009, the Mayor of São Paulo decided that the new website, Keeping an Eye on Public Costs, should include a list of all civil servants attached to the municipality – including 147,000 employees of the central administration and another 15,000 employed indirectly – with their posts, salaries and places of work.70 Two associations of civil servants (representing professors, engineers and architects) filed lawsuits against this decision. They were granted an urgent provisional decision by the Superior Court of São Paulo, and the information was taken off-line. The two associations argued that the disclosures would, among other things, breach their constitutional rights to privacy and security of person. The São Paulo Superior Court held that the information could put people at risk, and also accepted some procedural arguments. The Municipality appealed to the Supreme Court. On July 8, 2009, the Supreme Court upheld the Mayor’s decision to order the posting online of the salaries of all municipal civil servants.71 Justice Gilmar Mendes, who ruled on the case, referred to the fact that the Internet has transformed the citizen-State relationship, particularly in relation to social control over public expenditure. He recognized that in some cases, openness could legitimately be limited. However, in this case, the public interest in having the information was stronger than the rights of civil servants. Moreover, enforcing a judicial decision that undermined the Municipality’s policy of transparency in favor of individual rights would violate the “public order.” 65 Salaries are available at: http://deolhonascontas.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/index.htm. 66 Available at http://www.camara.sp.gov.br/legislacao.asp. Decree N 50.070, 2008, available at http://74.125.113.132/search?q=cache:A122u2ghdPQJ:ftp://ftp.saude.sp.gov.br/ftpsessp/bibliote/informe_eletronico /2008/iels.out.08/iels188/M_DC50070_021008.pdf+DECRETO+N%C2%BA+50.070,+DE+2+DE+OUTUBRO+DE+2008&cd=1&hl=ptBR&ct=clnk. 68 Constitution of Brazil, promulgated in 1988, Article 173, available at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constitui%C3%A7ao.htm. 69 1967, article 5, available at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil/decreto-lei/Del0200.htm 67 Article 19 press release, “Brazil: Supreme Court OKs Publication of Civil Servants’ Salaries,” July 14, 2009, http://www.article19.org/pdfs/press/brazil-supreme-court-oks-publication-of-civil-servants-salaries.pdf. 71 See Decision of the Supreme Court, in Portuguese, submitted with these Comments. 70 13 e. Israel In Israel, the Treasury publishes an annual report that lists the salaries of several thousand officials in the public sector, including those employed by government-controlled companies, companies controlled by local authorities, and companies or legal entities that receive more than 25% of their funding from the state (including, e.g., public health service providers). Companies are required to disclose the compensation of all employees; the salaries of employees that exceed a certain threshold (currently 17,000 NIS – approximately USD $4,000 – per month) are made publicly available through an online database.72 Companies must disclose information regarding salary, any bonus or other remuneration, and pension and other deferred payments. The Treasury publishes two reports: one is very long and includes the full data on several thousand posts, and the other is a shorter report that includes just those entries that seem not to be in line with the Treasury’s guidance. Although the reports do not include names, they do include positions, and it is easy for the media and the public to decipher to whom an entry refers (e.g., the deputy director of XYZ hospital). IV. Conclusion We believe that the Regulations proposed by the Consejo are a crucial step in ensuring the vitality of principles of transparency and openness in Chilean corporate governance. In particular, by requiring disclosure regarding remuneration practices of SOEs, the Regulations will permit shareholders, taxpayers and the public to gain valuable insight into an important aspect of the corporate process. Increasing access to this information will, as discussed above, produce numerous potential benefits to companies, shareholders and the public at large. By reducing agency costs, increasing accountability and potential outrage costs, and signaling the pursuit of remuneration norms, the Regulations will incentivize management to give serious consideration to the interests of shareholders, taxpayers and the public in designing remuneration packages. The Regulations will also increase public confidence in companies and assist with commercial competition. This benefit is significant, particularly in the current environment in which public distrust of companies (both governmental and non-governmental) is perhaps at an all time-high given the economic crisis. With increased transparency, the public will be better able to judge whether the remuneration practices of Chilean companies, and the corporate governance principles of such companies generally, are in line with best practices, both within Chile and internationally. Moreover, the proposed Regulations are in line with the clear international trend towards increased transparency in the area of remuneration. The increasing globalization of securities markets makes it important that Chilean standards of corporate governance accord with international best practice. For countries trying to attract financial capital, corporate governance is essential in bolstering the confidence and commitment of potential investors, contributing to corporate competitiveness and facilitating long-term economic development. 72 See http://hsgs.mof.gov.il/ViewReportPage.aspx. 14 We believe that the proposed Regulations are a welcome addition to Chile’s commitment to transparency. In addition, we would like to propose a few refinements to the disclosure requirements that would allow Chile to realize a maximum benefit from its disclosure regime: We note that the portion of the Regulations requiring disclosure of remuneration focuses on raw data and summary presentation of remuneration figures. The Consejo may wish to consider requiring companies to not only disclose the remuneration of executives and directors, but also require them to discuss the decision-making processes management undertakes in designing and setting remuneration. As commentators have noted, although disclosure plays a crucial role in regulating remuneration, raw data without context often does not paint a full picture.73 Shareholders and the public may be better equipped to evaluate and assess remuneration with such qualitative information as is required in the CD&A in the United States and Canada (see Section II(a) and (b) above). The Regulations do not appear to require companies to include disclosure regarding equity compensation, retirement benefits or deferred compensation. We believe these forms of compensation should be subject to disclosure as they are an increasingly material portion of the remuneration packages of public company executives. The Regulations do not appear to require disclosure regarding related party transactions. Disclosures of these types of transactions provide valuable information regarding transactions that are often subject to conflicts of interest and present unique opportunities for mismanagement and corruption. We note that the Regulations would require companies to update information made publicly available on a monthly basis. Although there is a clear benefit to requiring current and accurate information, it may be a more efficient allocation of resources to require these updates to be made on a less frequent basis (perhaps quarterly or yearly). We note that the disclosure regimes in North America and Western Europe do not require such frequent updates. __________________________ Sandra Coliver Senior Legal Officer, Freedom of Information & Expression Open Society Justice Initiative New York, NY U.S.A. September 21, 2009 See Bahar, supra note 6, at 49 (“perhaps the best way to improve accountability would be to focus disclosure on the process and the policies”); see also Jeffrey N. Gordon (Professor of Law, Columbia Law School), Executive Compensation: If There's a Problem, What's the Remedy? The Case for “Compensation Discussion and Analysis” (J. CORP. L., Working Paper No. 273, 2006), available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=686464. 73 15 ■ Other Description of compensation element: ■ Executive compensation philosophy ■ Overview of bonus ■ Overview of LTI plans ■ Description of pension ■ Any payouts to departing executives ■ Any peer groups used Norway Portugal Spain Sweden Switzerland UK ■ Long Term Incentives (LTI) Netherlands ■ Pension Italy ■ Benefits Ireland ■ Bonus Germany ■ Fees France Executive remuneration only provided as aggregated amount Executive compensation provided for each executive by name separately Elements of compensation disclosed in tabular format: ■ Salary Finland Executive compensation disclosed in the annual report and accounts Executive directors covered CHILE Exhibit A All directors All directors Board members Board members Board members Board members Board members Board members Board members Board members Board members Board members and senior management All directors CEO only Highest paid executive All types of stipends Severance Severance Severance, long term costs Severance, small perks CEO only [] [] [] [] [] [] [] [] [] Disclosure of performance required Shareholders vote on the remuner. report Severance Change of control provisions Performanc e graph Note: The disclosure rules in each country typically relate to all companies listed on that country’s stock market. Shareholder vote typically advisory. © 2007 Mercer LLC. [] = Typically not provided in all annual reports.