Three Main Organizational Issues

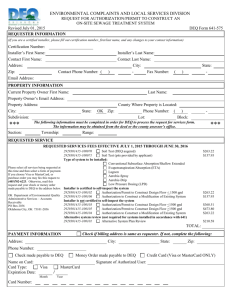

advertisement