Bible translation as purposeful communication

advertisement

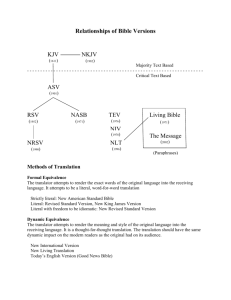

1 Bible Translation as Purposeful Communication: One Word, Many Versions D.C. Chemorion Abstract1 Translation is a secondary form of communication in which the senders and receivers belong to different cultures and languages. In order to communicate, senders and receivers need the help of a translator who is familiar with the lingua-culture of both the sender and the receiver of the message. Translators bridge the gap between situations where the differences in verbal and non-verbal behavior are such that there is not enough common ground for the sender and receiver to communicate effectively by themselves. For over two centuries now, Bible translators have acted as essential bridges of communication between the biblical authors and contemporary recipients of the word of God. Whereas different groups of people are happy to read the word of God in one version or the other, many people do not understand why the same word of God has been rendered in different versions. The question is: Why do we have many versions of the Bible? The purpose of this presentation is to highlight the nature of Bible Translation as purposeful communication and the necessity of different versions of the Bible in Africa. The presenter will also propose a strategy for producing function oriented alternative translations for an African context. 1.1 Introduction Translation is a secondary form of communication in which the senders and receivers belong to different cultures and languages. In order to communicate, senders and receivers need the help of a translator who is familiar with the lingua-culture of both the sender and the receiver of the message. Translators bridge the gap between situations where the differences in verbal and non-verbal behavior are such that there is not enough common ground for the sender and receiver to communicate effectively by themselves. For over two centuries now, Bible translators have acted as essential bridges of communication between the biblical authors and contemporary recipients of the word of God. Whereas different groups of people are happy to read the word of God in one version or the other, many people do not understand why the same word of God has been rendered in different versions. The question is: Why do we have many versions of the Bible? The purpose of this presentation is to highlight the nature of Bible Translation as purposeful communication and the necessity of different versions of the Bible in the African context. In addition, the article also proposes a Participatory Approach to Bible Translation as one of the viable strategies that could be applied in the production of alternative versions of the Bible in Africa.. 1.2 Bible Translation as secondary communication Bible translation may be defined as a process of re-expressing biblical information from its source language (SL) using the verbal forms of a receptor language (RL) for a given communicative function and by means of writing. This process may also be known as The ideas expressed in this article are informed by the author’s own dissertation in the field of Bible Translation at the University of Stellensbosch. See Chemorion (2008). 1 2 “Bible translating.” In a secondary sense, the term Bible translation also refers to the general field of study which deals with the science and art of rendering Scripture from one language to another, or to denote the product of the translation process, for example “an English Bible Translation”. The nature of Bible translation as a process of secondary communication may be described as follows: A Biblical author was the initial source (S1) of a biblical text, which he/she composed as an initial message (M1) for initial recipients (R1) who lived in biblical times and understood the biblical language used. This can be illustrated as using the following modified Aristotelian Source-Message-Receptor (SMR) model of communication. S1=====M1===R1 S2=====M2===R2 S3=====M3===R3 In the SMR model shown above, the sender (S1) of the message (M1) shares a common space and time with the receiver (R1) of the message. However, Bible translation is an ancient text whose original senders and recipients are no longer living. The original message is extant but the contemporary recipients in a given community may not be able to decode the message due their inability to read the SL. It therefore becomes necessary for translators to stand in the communication gap between the ancient biblical author and the contemporary readers. In this case, a translator who supposedly has the competence to decode the message in its original source SL form acts simultaneously as the first recipient R1 as well as a secondary sender (S2) of a re-encoded message (M2) for a 3 contemporary receptor audience (R2). In some cases, Bible translators are not able to translate directly from the biblical languages. Instead they translate from secondary sources, which are also translations of the original texts. In such cases, the translator effectively becomes the secondary recipient (R2) of the repackaged message as well as a third step sender (S3) for a repackaged third step message (M3) which is then made accessible to a third step receptor audience (R3)2. It is important to note that the act of translating is not only a linguistic operation, but it is also a way of facilitating communication between members of different cultures. This means that like any other type of communication, translation is goal oriented and it is aimed at achieving a certain communicative function as discussed in the following section. 1.2.2 Bible translation is function oriented Recent studies in the field of Translation Studies has shown that no single translation can communicate effectively all the aspects of a source text. Every Bible translation process is therefore undertaken with a specific skopos (communicative purpose) in mind. It is the intended skopos of the translation that determines how the information obtained from the source texts is reflected in the target text. This means that a single type of translation cannot fulfill all the communicative functions that various subsets of a community may expect from a translation of the Bible. In the past centuries when the science of translation had not come into being, new translations of the Bible would be received with a lot of suspicion. However, today the Bible is translated in very many ways and for a variety of purposes (Noorda 2002:8). One word of God has effectively been effectively rendered in many versions depending on the skopos of the translation. For the English speaking audiences, many modern English versions of the Bible have been produced with different functional emphases, based on real life experiences and 2 Although third step translations of Scripture are better than having no Scripture at all, it must be noted that basing mother tongue translations on existing second step translations (such as English Versions) is likely to introduce a certain degree of translation difficulties and distortions that would not have been fewer if one was able to use the original source texts as the basis of the translation. It is therefore important for translators to be competent in biblical languages in order to translate directly from the original texts 4 specific scriptural needs of various audiences. It is now estimated that there are over 500 versions of the Bible in English language since John Wycliffe produced the first handwritten English translation of the New Testament in 1383. Examples of such versions include versions with a study emphasis which are useful for students, versions designed to be more popular for a wider readership, versions that are more literary in style, versions that have a more protestant or more catholic background, versions designed to be particularly suitable for liturgical use, and so on (Hagreaves 1993:70-73). 1.3 Function oriented types of Bible versions Given the diversity of the purposes for which translations are needed, two main broad categories of Bible versions can be drawn: Documentary (foreignizing) translations and Instrumental (domesticating) translations (Cf. Munday 2001:81). Documentary translations serve as documents, which expose the original form of communication between the author of the source text and the source text recipient (Nord 1997:47). Literal translations of the Bible such as the King James Version, Revised Standard Version, New International Version, Jerusalem Bible, New American Standard Bible, and the Revised English Bible may be put in the category of documentary translations. An extreme form of a documentary translation is an interlinear translation which reflects the morphological, lexical, and syntactic features of the source language system as presented in the source text. Instrumental translations are produced in forms that are independent of the forms of their source texts. These types of translations are intended to fulfill communicative purposes without the recipients being conscious that they are reading or hearing a text, which previously had a different form and was used in a different communicative situation (Cf. Nord 1997:50). In other words, instrumental translations are shaped in such a way that readers would read them as though they were original texts written in the target language. The form of the text is usually adapted to target culture norms, conventions of text type, genre, register and tenor. Readers are not supposed to be aware they are reading a translation at all (Nord 1997:52). Majority of modern versions of translations are instrumental. Examples include: Good News Bible, New Living Translation, Biblia 5 Habari Njema, Contemporary English Version, and a variety of recent mother tongue translations in Africa. 1.4 The necessity of different versions of the Bible in Africa In Africa, many communities have only a pioneer mother tongue translation of the Bible, which is either complete or in progress. Like any other pioneer translations in the rest of the world, the overriding communicative function for the pioneer African translations is the missionary function. In other words, these translations were or are being produced with a missionary objective in mind. They are essentially designed to be part of the missionary effort of establishing the church in the dark continent of Africa. We need to note that while translation is yet to begin in some of the African languages, the translations in some of the communities are long overdue for revision. For example, some of the words used in the older versions have either acquired different meanings or have simply become archaic to younger generation of readers 3. In some cases, the translations were drafted by missionaries and their style lacks the natural flow of indigenous language. Most of the first translations are also very literal as they keep closely to the linguistic forms of the Hebrew and Greek texts, which make to give wrong meanings in some texts. In addition, some of the pioneer translations were done for particular denominations and there is need to come up with “Inter-church” translations acceptable to all Christians. Although missionary translations have served and continue to serve their purpose fairly well, other African translations with different functional emphases are needed. Christianity is now well established in many parts of Africa and the goal of translation need to expand its horizon from a missionary function to catering for other specialized 3 Cf. Kikuyu translation Deuteronomy 28:13, translation of the term for tail in Kikuyu has acquired a different meaning causing problems in public reading of the text for the current generation. 6 functions4. For an institution like St. Pauls we need versions of mother tongue translations that can be used as bases for biblical exegesis. 1.6 A strategy for producing alternative translations The task of determining and producing alternative translations is by no means an easy one. The prime question is: What strategy can translators use to design a scripture version that is not only complementary to the existing translation but also acceptable to the intended target audience? In the following section, a participatory approach to Bible translation (PABT) is presented as one of the viable strategies that could be used to identify an alternative function-oriented and acceptable Scripture version for an African context. The strategy in build on the theoretical framework of a functionalist perspective of translation, which suggests among other issues, that in the real world of translation, the central factor for determining how a translation is done may be found in the question: Does the translation fulfill the function that its initiator(s)5 had in mind for it? (Nord 1997:30). The PABT approach aims at the active involvement of the target language community in the design of the translation brief, which guides the actual process of Bible translation. In this approach the most important participants in the translation process are: the target language community, the sponsoring translation organization, and the source text author. As it has been discussed in the previous section, the target language community in the PABT approach is allocated the role of “initiator-cum-addressee” for the translation. There are three important steps to be followed in involving members of the community in the technical aspects of translating the Bible into mother tongue. These steps are: the engagement step, the source text analysis step, and the transfer step. The whole of the participatory process is illustrated in the following diagram. As De Vries (2001:312) observes “the situation in which only one type of translation has the monopoly should only be temporary”, because “a single translation is not enough for the various things people want to do with the Bible”. 5 “Initiator” is a technical term, which Nord (1997:20) defines as “the person, group or institution that 4 starts of the translation process and determines its course by defining the purpose for which the target text is needed.” 7 Step 1: Engagement. Target language Community needs a translation Rapport and Negotiation over translation brief/skopos Translation Brief: to guide the translation process. Translation acceptable to target text audience Step 2: Source text analysis. Translation agency provides the required expertise for translation Source text analysis Step 3: Transfer. Translation agency translates the source text in accordance with the translation brief Translation product that is loyal and acceptable Source text author provides the source text The source text message Translation loyal to source text author Figure 1: Diagram illustrating the process of translation in PABT 1.6 Conclusion Translations are produced to serve certain communicative functions. It is necessary to have as many translations of the Bible in order to fully understand the Bible from different perspectives. The need for alternative versions in an African context is urgent but without suitable strategies, the task of doing such translations can be very difficult. 8 The PABT strategy proposed in this presentation may be applied to produce acceptable and function oriented translations. Bibliography Chemorion, D.C., 2008. Translating Jonah’s Narration and Poetry Into Sabaot. Towards a Participatory Approach to Bible Translation. Stellenbosch University. De Vries, L., 2001. Bible Translations: Forms and Functions. The Bible Translator. Vol. 52 (3):306-319. Hargreaves, C., 1993. A Translator’s Freedom: Modern English Bibles and Their Language. Sheffield: JSOT Press. Munday, J;, 2001. Introducing Translation Studies. London: Routledge. Nord, C., 1997. Translating as a Purposeful Activity: Functionalist Approaches Explained. Manchester: St. Jerome. Noorda, S., 2002. New and Familiar. The Dynamics of Bible Translation. In: Brenner, A., & Van Hentem, J.W., (Eds.) Bible Translation on the Threshold of the Twenty First Century: Authority, Reception, Culture and Religion. London: Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 8-16. Wendland, E.R. Buku Loyera. An Introduction to the New Chichewa Bible Translation. Blantyre: Christian Literature Association in Malawi.