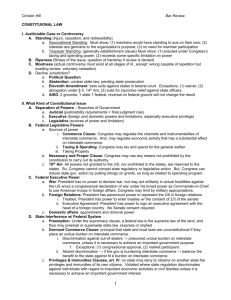

constitutional law outline

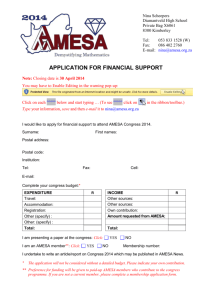

advertisement