File

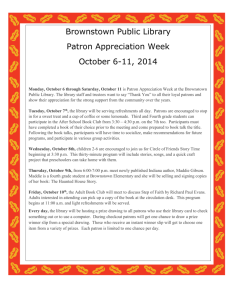

advertisement

Shaula M. Stephenson LIBR 266 1 Convincing the Patrons: The Public Relations Campaign for Deselection The task of deselecting or “weeding” materials from a library’s collection is fraught, to say the least. Aside from the pragmatist-versus-bibliophile death match that likely ensues in most librarians’ minds when faced with the prospect of discarding a publication, there is often public backlash when it is discovered that a library, especially in hard economic times, is getting rid of materials. It doesn’t have to be a large project, but the idea of discarding part of the collection is sufficiently taboo to create a great deal of unpopular public opinion. And that’s when the outcry begins. Someone once said, “The best defense is a good offense” and this philosophy holds true when a library begins a large deselection project. It is vital that the library make clear to patrons the benefits and necessity of trimming the collection. The brouhaha at the San Francisco Public Library in 1996 is a fine example, on many levels, of what not to do. As Will Manley pointed out, “[i]f San Francisco Public made a mistake, it was in timing. If they had to do it all over again I’m sure they would not remove 100,000 books all at one time and haul them down to the city dump” (Manley, 1996). I suspect they would also take some time to educate the patrons who had worked so hard to raise money for the new branch. Manley (2003) advocates “keep your weeding program out of the public eye,” which might be sound advice for small, periodic weeding, but can only spell trouble for large projects. When San Francisco City Librarian Kenneth Dowlin refused a public request to review the card catalog, resulting in Baker v. San Francisco Public Library, he threw fuel on the fire that was public distrust and outrage. No matter the truth, it looked like the library had something to hide. One effective way to combat public fears and suspicion about a large-scale project intended to the reduce a library’s collection is to run a thorough and aggressive public relations Shaula M. Stephenson LIBR 266 2 campaign in advance of the project in order to educate and involve the public and ultimately solicit their support. One of the primary misconceptions driving many of the objections to deselection projects is that a bigger collection is a better collection. There is a superstore mentality prevalent among American consumers, especially, that a larger selection equals a better selection; so to them, reducing a collection means that their choices are being reduced. Another assumption made by patrons is that when materials are removed from the library, they are automatically destroyed. Perhaps they are imagining some kind of animal control center for books where the sickly or unwanted publications are put down if they aren’t adopted. If patrons can be reassured that books are not being hauled to a landfill and dumped en masse or heaped onto bonfires reminiscent of Nazi book burning events, the next concern is that books are being removed from the collection as part of a personal or organizational agenda. In short, that deselection is being used as a method of censorship. Given librarians’ history as passionate defenders of free thought, the concerns about censorship are baffling. However, they are pervasive and must be addressed if a project is to go forward with minimal protest. The best weapons against the fears of wanton destruction and censorship are documentation and transparency. It is vital to have a clearly written and well-thought out collection management policy that is publicly available. The policy is tangible reassurance that the library regularly reviews the condition and currency of its collection and that materials are removed from the collection when they contain outdated information; are in poor physical condition; are unneeded duplicates; or when their contents do not fall within the scope of the collection development policy. It is important to emphasize that removal of materials is not the Shaula M. Stephenson LIBR 266 3 decision of one librarian alone; there are a number of people involved before the materials are retired. Equally powerful tools of reassurance are Section II of The Library Bill of Rights and The Freedom to Read statement. A few lines of “Libraries should provide materials and information presenting all points of view on current and historical issues. Materials should not be proscribed or removed because of partisan or doctrinal disapproval” (Library Bill of Rights, 1996) or “It is in the public interest for publishers and librarians to make available the widest diversity of views and expressions, including those that are unorthodox, unpopular, or considered dangerous by the majority” (The Freedom to Read Statement, 2004) are likely to provide solace to any number of suspicious members of the public. Side by side with concerns about the physical removal and disposal of materials sits the question of why a library is getting rid of items that were purchased with public money. 42.6% of librarians listed a wide variety of negative complaints from the public about the weeding process, ranging from particular items, especially classics, being missing from the shelves, to anger at finding hundreds of books discarded in local dumpsters, to outrage that taxpayers’ money is being wasted when items are weeded (Dilevko & Gottlieb, 2003). Combating these fears is as simple and as complicated as educating patrons about the fiscal and integral benefits of a trimmed and carefully considered collection. The integral benefits of reviewing a collection are well-documented: make more space on the shelves; present attractive materials that are in good repair; provide current and reliable sources (Allen, 2010); and improve the overall quality of the collection (Dubicki, 2008). The fiscal benefits of deselection are more subtle but equally important. Studies have shown that a well-tended collection stimulates circulation, which is often the benchmark by Shaula M. Stephenson LIBR 266 4 which many measure libraries’ overall success. “Penelope McKee, after using the Slote method, observed that there was ‘a strong positive relationship between declining stock [due to weeding] and increasing circulation’” (Dilevko & Gottlieb, 2003). Higher circulation numbers and greater patron attendance provide leverage with which the library’s administration can request more funding. Additionally, there are the proceeds from any sales of deselected books to add to the library’s coffers. These are the dragons that must be slain in order to proceed with a sizeable deselection project. The public must be convinced that Allen is correct when she writes, “Destruction of books brings up images of censorship and book burning, but it is better to have worthless books in the trash than have trash on your shelves” (Allen, 2010). Gray & Metz (2005) lay out the necessary steps for running a public relations campaign to promote understanding of a proposed weeding project in an academic library, but their strategies are applicable to other kinds of collections. For inspiration, one should look to The Wyoming Libraries Campaign. [L]aunched in February 2006 … [t]his creative and visually expressive campaign combined images of Wyoming with things from around the world you could learn about at the library: a windmill sits atop the Eiffel Tower; a pickup tows the Trojan horse. The results: Wyoming libraries saw a 21% increase in card holders from 306,550 in 2005 to 389,050 in 2006 (Outrider, 2007). The Wyoming Libraries Campaign took steps that can be applied to any effort designed at winning public approval of a project. By exposing to the public what the libraries had to offer, they drew positive public attention and increased their membership. Shaula M. Stephenson LIBR 266 5 Campaigns to gain public approval must outline for the patrons the benefits to a wellweeded collection; present it as trim, sleek and relevant. Think sports cars and super models; think sexy and hip. The first step in convincing the patrons is for the staff members heading the project to spend some time determining the focus of the campaign. Who is likely to object to the project? Who is likely to support it? When the supporters and detractors have been identified, it will be helpful to run an analysis of the situation. In an internal library matter - like a collection review - the primary advantage is the staff’s intimate knowledge about the deselection process and its benefits to the library and the patrons. The most likely weakness is the hesitancy expressed by many librarians about deselection (Dilevko & Gottlieb, 2003). The trick is to realize that this is an opportunity to present the public with the option to provide input about the process and the fate of the discarded library materials. Once it is clear what the campaign is facing, the objective must be clarified. In order to proceed with the deselection project, the public must be educated about the process and their support gained. This is where the Library Bill of Rights and the Right to Read statement will be most useful. Pertinent sections from both documents should be paraphrased in the key messages to the patrons. Remind them of librarians’ history of defending citizens’ rights of free access to information. Lay out the benefits of a select collection. Publicize any plans for the disposal of materials that aren’t sold; emphasize that materials that cannot be donated or repurposed will be recycled or disposed of in an environmentally responsible way. Recycling has been demonstrated to ease some of the guilt felt by library staff at having to dispose of materials. “One of the most mentioned impacts of collection disposal Shaula M. Stephenson LIBR 266 6 was how it affected staff emotionally. Many discussed the guilt and distraught they experienced in deselection and disposal. Recycling was comforting, when present, as it was in-line with their environmental values” (Urness, 2010). The Wyoming Libraries Campaign made effective use of a number of slogans: “You can have my book when you pry it from my cold dead fingers,” and “My other card is a library card.” There is no reason that a well-planned deselection project cannot use the same method. Slogans like “The only good library is a trim library” or “Less to see. More to find” will capture the public’s attention in a way that “Reasons why deselection is good” simply won’t. Additionally, Ash (1985) suggests the use of the terms “library review program” or “library review project” rather than more traditional and less favorable terms like “weeding,” “pruning” or, even worse, “deselection.” It is difficult to gain the support of nebulous groups, so it is necessary to identify the groups and individuals who will be affected by the project and in what way they are already suffering from the unreviewed collection, even if they don’t know it yet. Occasional patrons will need to be shown that their collection is being overrun by shabby, out of date materials; librarians, volunteers, and possibly regular and involved patrons should recognize how much harder they are working to maneuver within the oversized collection; and Friends of the Library or other support groups should see that they are losing valuable revenue with outdated books sitting on the shelves. Though they are not necessarily patrons or actively involved in running the library, elected officials should be brought into play if at all possible. If libraries in their constituency begin to close, it does not reflect well upon local politicians. They are relatively high-profile individuals who can increase the exposure of the campaign. Shaula M. Stephenson LIBR 266 7 Now that the involved parties have been identified, it is time to craft key messages, which will target the groups whose support the library requires. Tell the patrons that a well-kept collection is more useful than an oversized, out-of-date collection. Convince the governing board that a review of materials can result in potential capital for the library through sales of discarded materials and resultant increased circulation. Cite Penelope McKee on the increased circulation of a trim library collection, if you must. Remind elected officials that a well-kept collection will increase circulation, which will result in a more robust library in the officials’ constituencies and will make constituents feel well-served. Also point out that public involvement in planning will foster the habit of civic involvement in general. How, you may ask yourself, will we reach so many people with a low budget? Make use of as many low-cost communication methods as possible. This is where the wonder of the digital world will hold libraries in good stead. Most libraries have an e-mail list of patrons who receive notices electronically. Make use of the already existing e-mail list to contact active patrons. A library web site is another excellent and low-cost venue for disseminating information. Create a page about the project on the library’s site; establish a blog to provide updates on the progress; invite public comment; be certain that an RSS feed is available so that subscribers can receive updates to the blog. Exploit social networking. If the library doesn’t already have a Facebook page, then create one and use it to keep fans informed about the project and, most importantly, its benefits. If the library isn’t on Twitter, establish an account and send out regular Tweets about the project. For target audiences who are less comfortable with technology, there are tried and true lo-tech methods. Gray & Metz (2005) suggest publishing an article in the staff newsletter, which is clearly not an option if the project is taking place at a non-academic library. However, large, Shaula M. Stephenson LIBR 266 8 clearly worded notices can be placed in strategic locations at the library and at nearby community centers. A letter-writing campaign to local papers would reach a broad portion of the community and provide an opportunity for a most of the library staff to participate. Librarians must be prepared to receive feedback from the public: a patron who cares enough to take note of the posted information is likely to care enough to make suggestions. Where the public is involved, Gray & Metz’s discussion of flexibility is vital. A non-academic library will not have to confront the concerns of faculty for their particular fields of interest, but that doesn’t mean that the patrons might not have insights into what portions of the collection are most valuable. Granted, there will be some outrageous input – “You can’t get rid of that copy of the Washington Post from 2002; my dog’s obituary is in there!” – but overall, who better to give ideas about what is most valued in the collection than the people making use of the materials? Involvement begets questions: it is inevitable. If patrons feel they are part of the process they are going to want answers to their questions and someone must provide them. Gray & Metz (2005) cite the director of their collections department as the primary source of answers and that idea can apply to non-academic libraries as well. The library’s patrons must be told not only that the library is refining its collection but why and how. If librarians are squeamish about the idea of deselection, imagine how the public feels. It is important that the library staff be willing and available to answer patrons’ questions about the project. Public attention will likely attract media attention at some point. With a little preparation, it is easy to turn the media attention to the advantage of your project. If you anticipate some public reaction, prepare some written statements in advance. Practice answering some difficult questions. DON’T BE CAUGHT OFF GUARD. If you get a call from a reporter you can always Shaula M. Stephenson LIBR 266 9 tell them you’ll call back. Take some time to compose a statement … and always stress the positive aspect of weeding (Klopfer, 2010). If the project’s time frame allows, holding one or two community meetings will give interested patrons the opportunity to voice concerns or share suggestions with the library staff. When increasing numbers of patrons begin to participate actively in the planning the process it will be clear that the campaign has been successful in reaching out to patrons. The campaign should be conducted in stages. Contact with the public should be initiated approximately three months before the project begins. Initial contact should only indicate that the collection review project is imminent and that it will be a great benefit to the patrons and the community. Notices should be posted and e-mails sent, the blog, Facebook, and Twitter accounts should be established. It takes time for fans to accumulate on Facebook and for people to begin following a Twitter feed. The letter-writing campaign should also commence right away to give the letters time to be published. Two months from the beginning of the project, information should be released about the specific plans for the project: what sections of the collection will be reviewed first; the criteria used to decide which publications should be removed; how many librarians will make the final decisions about removal; and the various options proposed for disposal. This will give the public time to consider the specifics of the project and to offer suggestions or concerns. As the beginning of the project approaches, updates should become more frequent, even if it is just posting on Facebook articles about the benefits of collection review or a Tweet about particularly worn or out of date material that will likely be removed. The blog Awful Library Books (Hibner & Kelly, 2010) is an excellent example of how to present collection review as a desirable and entertaining process. Klopfer (2010) suggests setting aside some truly grievous Shaula M. Stephenson LIBR 266 10 materials for display in order to impress upon patrons that some things really do not need to stay on the shelves. Once the project has begun, the updates can be less frequent, but they should continue. Again, it is wise to use levity and hold up as examples some of the obnoxiously dated materials that are being removed from the collection. The ongoing updates are also a good opportunity to tout the Friends of the Library sale that will almost certainly follow the completion of the review process. Highlight any innovative or socially responsible solutions to disposing of the materials. If the library plans to donate ten boxes of graphic novels from the 1990s to a juvenile detention facility, be sure to mention it. Continue to encourage patrons to contribute their ideas for organizations that can use donations of materials. The actual cost of running a public relations campaign in this way will be minimal. The primary outlay will be staff time to manage the social networking aspects of the campaign and to write letters to the newspapers. With some forethought, planning and effort, debacles like the San Francisco Public Library (Baker, 1996) and Chicago’s Sulzer Regional Library (Eberhart, 2001) can be avoided. The public can be engaged and included in the process and come away feeling reassured that the library is behaving with candor and not attempting to reduce the collection for some nefarious purpose. Take the time to convince the patrons and a clash between the library and the public can be averted, even with large collection review projects. Shaula M. Stephenson LIBR 266 11 References Allen, M. (May/June 2010). Weed ‘em and reap: the art of weeding to avoid criticism. Library Media Connection, pp. 32-33. American Library Association. (2004). The Freedom to Read Statement. Chicago, IL: American Library Association. American Library Association. (1996). Library Bill of Rights. Chicago, IL: American Library Association. Ash, L. (Winter 1985). Old dog; no tricks: perceptions of the qualitative analysis of book collections. Library Trends, pp. 385-394. Baker, N. (1996, October). Letter from San Francisco, “The author vs. the library.” The New Yorker, p. 50. Dilevko, J. & Gottlieb, L. (2003) Weed to achieve: a fundamental part of the public library mission? Library Collections, Acquisitions, & Technical Services 27, pp. 73-96. doi:10.10106/S1464-9055(02)00308-1 Eberhard, G.M. (2001, October). Furor erupts over Chicago weeding program. American Libraries, pp. 22-25. Gray, C. & Metz, P. (May 2005). Public relations and library weeding. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 31(3), pp. 273-279. Hibner, H, & Kelly, M. (2010, August). Awful Library Books: the shame of library collections! [Web log]. Retrieved from http://awfullibrarybooks.wordpress.com/ Klopfer, K. (2010). Weed it! for an attractive and useful collection. Western Massachusetts Regional Library, Berkshire Subregion. Retrieved from http://www.wmrls.org/services/colldev/weed_it.html#How Manley, W. (December 1996). S.F.P.L blues. American Libraries, p. 96. Shaula M. Stephenson LIBR 266 12 Manley, W. (November 2003). Readers need weeders. American Libraries, p. 80. Poller, M. (March 1976). Weeding monographs in the Harrison Public Library. Collection Management 1(1), pp. 6-7. Urness, C. (2010, August). Library Collection Disposal: new tools for media management. Paper to be presented at Environmental Sustainability and Libraries SIG, World Library and Information Congress: 76th IFLA General Conference and Assembly, Gothenburg, Sweden. Wyoming libraries campaign wins John Cotton Dana Award. (January 2007). The Outrider 40(1). Retrieved from http://www-wsl.state.wy.us/slpub/outrider/2007/Jan2007.html