Re-Imaging Inanna: The Gendered Reappropriation of the Ancient

advertisement

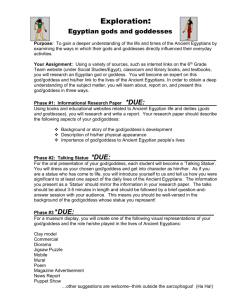

Re-Imaging Inanna: The Gendered Reappropriation of the Ancient Goddess in Modern Goddess Worship Abstract Re-Imagining Inanna: The Gendered Reappropriation of the Ancient Goddess in Modern Goddess Worship examines the specifically gendered reconstruction of the ancient Mesopotamian deity Inanna in modern Goddess worship. This paper argues that the reconstruction of Inanna in modern Goddess worship is an imaginative process based upon unexamined gendered assumptions of what is properly feminine for a great goddess. The result of this process is a constructed image of Inanna that is incongruent with the personality of Inanna as imagined in ancient Mesopotamia. Moreover, this incongruence leads to an examination of the Pagan approach to history and an analysis of the sociological features present in contemporary Paganism that allows for these selective reconstructions. Imagine a gathering of prominent feminist theologians, historians, and commentators. Visualize a San Francisco dinner party attended by Merlin Stone, Carol Christ, Luisah Teish, Starhawk, Charlene Spretnak, and Jean Bolen. Such is the setting presented in the National Film Board of Canada’s short film titled Goddess Remembered.1 Amidst the sounds of glasses, plates, and spoons, the participants narrate their personal encounters and discoveries of the Goddess. These nostalgic tales are periodically interrupted by the soothing tones of sweet music supporting the serene voice of an anonymous narrator waxing nostalgic for ancient Goddess religion. Eventually the viewer is presented with an image of England’s Silbury Hill. Described as a Neolithic monument to the Goddess, the conical shape of Silbury Hill rises above the green English countryside, framed by a clear blue sky punctuated by soft white cumulus clouds. An image of sheep grazing on lush grass gives way to a cool, clear, bubbling stream. The narrator recites: 1. Goddess Remembered, videocassette, produced by Studio D (city?: National Film Board of Canada, 1989). © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004, Unit 6, The Village, 101 Amies Street, London SW11 2JW. O Lady, your breast is your field. Inanna, your breast is your field. Your broad field pours out plants. Your broad field pours out grain. Water flows from on high for your servant. Bread flows from on high for your servant. Pour it out for me, Inanna. I will drink all you offer.(2) Inanna is, of course, none other than the Sumerian Queen of Heaven, highly regarded throughout Mesopotamian history as the goddess without rival. The above verse is a brief passage from the Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi. Described as the world’s first love story (3) this tale and Dumuzi’s words reveal more than his arousal and desire for Inanna. This passage also depicts one way in which the ancient Sumerians imagined the provenance and immanence of their most beloved deity. Some 5,000 years after the appearance of the Sumerians in southern Mesopotamia the image of Inanna has been revived and used by Goddess Wicca (4) in a spiritual quest to re-imagine the goddess. Forming part of the religion of the Great Mother Goddess, the quest for Inanna is not simply a recovery of a lost goddess; rather, it is an eclectic, creative enterprise—a construction—conditioned by a feminist spiritual theology and informed by specifically gendered conceptions. Furthermore, the gendered reappropriation of Inanna is a magnifying glass through which sociological characteristics of contemporary Paganism and the role of history in Goddess worship may be examined. As a reconstructive enterprise, Goddess worship fosters a climate that allows for selective and constructed understandings of who and what the Goddess is. Douglas Cowan, in his forthcoming book titled Cyberhenge: Modern Paganism on the World Wide Web has developed a theory concerning, in his terminology, “closed source” and “open source” religions. (5) Partially inspired by the development of the Linux computer operating system, Cowan uses these terms to describe the degree to which religious practitioners in a given system have access to religious doctrine or 2. Ibid. 3. Diane Wolkstein and Samuel Noah Kramer, trans., Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer (New York: Harper and Row, 1983), xix. 4. In the literature the terms “Goddess Wicca,” “Goddess Religion,” and “Goddess Worship” are not clearly delineated. Though recognizing that some might argue specific and technical differences, for the purposes of this essay the terms will be used synonymously. 5. Douglas E. Cowan, Cyberhenge: Modern Paganism on the World Wide Web (New York: Routledge, forthcoming), 2. © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004. theology. Linux is unusual because individual users may download the operating system, access the source code, make improvements, and then upload the new version. Ideally this constant modification continually improves the software. (6) Subject to very similar processes, Goddess worship, as an “open source” tradition, “encourages theological and ritual innovation based on either individual intuition or group consensus.” (7) As an “open source” religion, Goddess Wicca is necessarily decentralized. There is no organizing body, and ritual working groups are free to operate in any manner they choose. (8) Issues of worship and practice are left to each ritual working group and ultimately to each individual. As Melissa Raphael states, Goddess religion is a great collage of deities with none more legitimate than the other. (9) In Goddess Wicca, the individual picks and chooses from the many images of the Goddess and decides what the Goddess means in his or her own worldview. Carol Christ’s statement is telling: “Ancient traditions are tapped selectively and eclectically, but they are not considered authoritative for modern consciousness.” (10) Not only does the “open source” nature of Goddess Wicca lead to an eclectic mix of individual interpretations, it also allows for the observation of the play of preconceived notions as practitioners access, interpret, and reinterpret the theology of the Great Mother Goddess. A very specific example may be observed in the gendered reappropriation of Inanna. Following the lead of Marija Gimbutas, many Goddess worshipers locate the origin of their religion in the opaque depths of the Paleolithic Age (25,000–30,000 BCE).11 Goddess worshipers argue that this was a matrifocal age when feminine ideals governed society. (12) Red ocher spread 6. Ibid., 2-3. 7. Ibid., 4. 8. Starhawk, The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess, 10th ed. (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1989), 28. 9. Melissa Raphael, “Truth in Flux: Goddess Feminism as a Late Modern Religion,” Religion 26 (July 1996): 200. 10. Carol Christ, “Why Women Need the Goddess,” in Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion, ed. Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1979), 276. 11. Merlin Stone, When God Was a Woman (San Diego: Harcourt Brace and Company, 1976), 10-12. 12. The following is a synthesis and summary of many sources. See particularly Marija Gimbutas, The Civilization of the Goddess (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1991), Stone, When God Was a Woman, and Starhawk, The Spiral Dance. For the archetypal understanding of the Goddess (from which many Goddess theologians seem to draw), see Eric Neuman, The Great Mother, An Analysis of the Archetype, trans. Ralph Manheim (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1963). © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004. around vulva shaped cave openings and on female corpses indicated a sign of respect for the female. Nude female figurines discovered in countless Stone Age settlements indicated the worship of the feminine embodied in a female deity. The perceived absence of fortifications and weapons indicated peace. The equity of burial goods between sexes indicates balance and harmony. The female was the creative force. Women invented agriculture and domesticated animals. Society lived in harmony with the earth without exploitation of planetary resources. For many Goddess worshipers, Inanna represents this time when power was feminine and communal while life, fertility, and death were respected. (13) Goddess worshipers contend that until the arrival of patriarchy in the third millennium BCE, Inanna held pride of place as the Mesopotamian representative of the culture of the universal great Goddess. A sampling of statements from a variety of sources reveals that re-imagining Inanna is a subjective, eclectic, and creative enterprise. For example, according to Los Angeles based ReWeaving Coven, Inanna is the Earth Goddess. (14) The ReWeaving Coven invokes Inanna in three annual ceremonies. During the Spring Equinox the coven recites the Sumerian hymn Inanna and the Huluppa Tree. At the Summer Solstice the coven recites the Courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi while at the Fall Equinox Inanna and the God of Wisdom is recited. For ReWeaving, Inanna embodies fertility, the wheel of birth, growth, death, and regeneration. Spiralgoddess.com emphasizes representations of Inanna as the goddess of love, fertility, and procreation. (15) The pliable nature of interpretation is further reinforced in the work of Patricia Telesco, author of several popular books for Pagan practitioners. According to Telesco, borrowing heavily from Mesopotamian mythology, Inanna is goddess of “mining, homes built underground, basements, and underground parking lots.” (16) The language Goddess worshipers use to describe Inanna is significant. According to Telesco, Inanna looks upon the world seeing its wholeness and unity, while her gentle tears wash from heaven, quenching the emotional fires that keep people apart in the world. (17) According to the Daily 13. Mary Wakeman, “Ancient Sumer and the Women’s Movement: The Process of Reaching Behind, Encompassing and Going Beyond,” The Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 1 (Fall 1985): 8 14. ReWeaving, “In Praise of Inanna,” http://www.reweaving.org/inanna.html (accessed February 7, 2004). 15. Spiral Goddess Grove, “Goddess Altar of Ishtar and Inanna,” http://www .spiralgoddess.com/Inanna.html (accessed February 7, 2004). 16. Sirona Knight and Patricia Telesco, The Cyber Spellbook: Magick in the Virtual World (Franklin Lakes, State?: The Career Press, 2002), 66. 17. Patricia Telesco, 365 Goddess: Daily Guide to the Magic and Inspiration of the © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004. Guide to the Magic and Inspiration of the Goddess, on August 20, the day of Inanna, the reader is to make an “Inanna wand” designed to manifest peace, oneness, and love. (18) According to Carol Christ, the Goddess is woman and she is the earth.(19) She is the life force that links humanity together with itself and with nature. The earth is the Goddess and the cycles of nature are the rhythms of her body. (20) “The Goddess is manifest in the world; she brings life into being, is nature and is flesh.” (21) Starhawk argues that the Goddess is the earth, a dark nurturing mother who brings forth all life. She is fertility and generation, the womb, the tomb, and the power of death. (22) She is the Queen of Heaven, the star goddess, ruler of knowledge, mind, and intuition. (23) As described above, these images of Inanna represent just one manifestation of the Great Mother. According to Starhawk, the Great Goddess has infinite aspects and thousands of names. (24) The Goddess is also Isis, Astarte, Aphrodite, Demeter, and Tiamat; her names are infinite. While the Goddess is known by many names in many cultures, she is, nevertheless, one great deity. (25) Indeed, she is “constantly changing form and changing face.” (26) While all the above characteristics are, without doubt, evident in Inanna’s personality, they are mere facets of the gem we call Inanna. Thorkild Jacobsen accurately describes Inanna as lady of infinite variety. (27) To the Sumerians Inanna was Nin-me-sar-ra, or, “Lady of Myriad Offices.” (28) Early Mesopotamian myths, however, depict Inanna as a war goddess. Goddess (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1998), August 20; no pagination, reference is by date. 18. Telesco. 19. Elizabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, “Roundtable Discussion: What Are the Sources of my Theology,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 1 (Spring 1985): 122. 20. Raphael, 200. 21. Starhawk, “Witchcraft and Women’s Culture,” in Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion, ed. Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1979), 263. 22. Starhawk, The Spiral Dance, 92. 23. Ibid. 24. Ibid., 22. 25. Goddess Remembered. 26. Starhawk, The Spiral Dance, 24. 27. Thorkild Jacobsen, The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976), 135. 28. Ibid., 142. © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004. A Neo-Babylonian text titled the Prayer of Lamentation to Ishtar (29) states: “O unequaled angry one of the fight, strong one of the battle, O firebrand which is kindled against the enemy, which brings about the destruction of the furious.”30 In a far older text (ca. 2400 BCE), Enheduanna, daughter of Sargon the Great and High Priestess of Nanna at Ur, writes of Inanna: The mountain who kept from paying homage to you—vegetation became “tabu” for it. You burnt down its great gates, Its rivers ran with blood because of you, its people had nothing to drink, Its troops were led off willingly (into captivity) before you, Its forces disbanded themselves willingly before you. (31) Inanna as war goddess is illustrated with even greater clarity in the following hymn: When I stand in the front (line) of battle I am the leader of all the lands, When I stand at the opening of the battle, I am the quiver ready to hand, When I stand in the midst of the battle, I am the heart of the battle, the arm of the warriors, When I begin moving at the end of the battle, I am an evilly rising flood, When I follow in the wake of the battle, I am the woman (exhorting the stragglers); “Get going! Close (with the enemy)!” (32) The multi-faceted nature of Inanna’s personality is portrayed well in the following verse: To pester, insult, deride, desecrate—and to venerate—is your domain, Inanna. Downheartedness, calamity, heartache—and joy and good cheer—is your domain, Inanna. 29. Ishtar is the Akkadian name of Inanna and equivalent to her Sumerian counterpart in numerous ways. Though originally of separate origin, the characteristics of the Akkadian Ishtar seem to have matched those of the Sumerian Inanna to such a degree that a combination of the two deities must have been natural. In the course of this article the names are used interchangeably. 30. Ferris J. Stephens, trans., “Prayer of Lamenation to Ishtar,” in Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, ed. James B. Pritchard, 2nd ed. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1955), 384. 31. S. N. Kramer, trans., “Hymnal Prayer of Enheduanna: The Adoration of Inanna of Ur,” in The Ancient Near East, vol. 2, A New Anthology of Texts and Pictures, ed. James B. Pritchard (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975), 137. 32. Jacobsen, 137. © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004. Trembling, affright, terror—dazzling and glory—is your domain, Inanna. (33) Inanna/Ishtar is also pouty and spoiled. When Gilgamesh rejects Ishtar’s advances in The Epic of Gilgamesh, she storms into heaven to seek redress: Ishtar was furious, and [went up] to heaven, Ishtar went up and wept before her father Anu, Her tears flowed before her mother Antu. “Father, Gilgamesh has shamed me again and again! Gilgamesh spelt out to me my dishonor, My dishonor and my disgrace.” Ishtar made her voice heard and spoke, She said to her father Anu, “Father, please give me the Bull of Heaven, and let me strike Gilgamesh down!” (34) Clearly, a presentation of Inanna as loving goddess of sex and fertility contrasts sharply with the unpredictable Inanna, violent war goddess and pouty, spoiled child of Anu. The manner in which Goddess worshipers ignore or downplay these aspects of Inanna’s sphere of influence reveals a selective reading that serves specifically modern gendered interests and preconceived notions of what is properly feminine for a great Mother Goddess. For example, war poses a problem for many in contemporary Goddess theology. Many commentators and theorists argue that war is a product of patriarchy and is virtually unknown in the civilization of the Goddess. (35) Marija Gimbutas states that the pattern of war and hierarchy is “typical of androcratic (male dominated) societies such as the Indo-European but does not apply to the gynocentric (mother/woman-centered) cultures.” (36) The re-imaginative characteristic of Goddess worship allows Carol Christ to specifically reject the Greek goddess Athena because of her association with war. (37) Christ further elaborates, “contemporary feminists have noted that most known patriarchal societies are characterized not only by the rule of men within family and society, but also by central 33. Ibid., 141. 34. Stephanie Dalley, trans., Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh and Others (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), 80. 35. Gimbutas, 48; Eisler, 17-18, 48-49; Starhawk, The Spiral Dance, 18. 36. Gimbutas, viii. 37. Mary Jo Weaver, “Who is the Goddess and Where Does she Get us?” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 5 (Spring 1989): 59. © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004. organization, hierarchy, class division, and slavery,” of which organized warfare is a result. (38) These gendered ideas, coupled with a flexible approach to history, necessarily lead to these conclusions. Christ reflects, “But I find it contradictory to criticize the warrior aspects of the God we have known as a dominating other and then to affirm the warrior Goddesses.” (39) In even stronger terms, Mary Condren argues that the term “war goddess” is an oxymoron and a distortion of patriarchal scholarship, as the image and the symbols of the goddess are opposed to battle. (40) Specifically, according to these characterizations, war is a characteristic of the masculine while peace and harmony are viewed as characteristics of the feminine. Problems abound with this interpretation of prehistory. Amongst the most problematic is an absence of texts. (41) Faced with this difficulty many scholars have turned to ethnographic studies of existing indigenous cultures as a potential window into the prehistorical age. Of course, this method relies upon a faulty assumption that traditional peoples and their practices are static and themselves without history. Another source of information is archaeology. Though looking at material remains, archaeology is often a “scattershot affair,” subject to individual interpretation through which identifying gender is notoriously difficult. A simple comment, posed by Cynthia Eller, reveals the difficulties with this approach. Specifically, concerning the identification of female skeletons, “a biological female may have been a social man (or vice versa), or . . . other gendered categories beyond the standard two existed.” (42) In other words, the identification of societal attitudes and values from material remains is often tentative and interpretative and fraught with unexamined assumptions. Setting aside for a moment the fact that the existence of primeval matriarchal societies is hotly debated, can we assume that the male, universally and throughout history, exercises a monopoly on violence, destruction, and war? A brief look at the Hindu goddess Kali illustrates that Inanna, as violent goddess, is not an aberration in world religion. In many 38. Carol P. Christ, Rebirth of the Goddess: Finding Meaning in Feminist Spirituality (New York: Addison-Wesley, 1997), 59. 39. Christ, Rebirth of the Goddess, 98. 40. Mary Condren, “Women and Goddess Traditions: In Antiquity and Today,” in Goddesses and the Lives of Women, ed. Judith Oschorn (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1997), 385. 41. For additional elaboration on the problems with a prehistorical matriarchy, see Cynthia Eller, The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory: Why an Invented Past Won’t Give Women a Future (Boston: Beacon Press, 2000), 81-93. 42. Eller, 88. © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004. striking ways the multivalent personality and domains of Kali resemble those of Inanna. The so-called “black Kali” sprang from the head of Durga issuing a primal cry into the skies. Armed with a sword, Kali devours and crushes the enemy with glee. (43) Like Inanna, she is imagined not only as the great fertility mother, but also as the great goddess of destruction. Goddess worshipers have at least two hermeneutical (Interpretive; explanatory) tools for explaining Inanna as goddess of war. Some argue, following Starhawk, that these aspects should be embraced but understood in a different manner. Despite pleading for a move away from “Patriarchal death cults and toward the love of life, of nature, of the female principle,” (44) Starhawk maintains that masculine principles are required to maintain balance in nature. (This is why, unlike Z. Budapest, Starhawk advocates male participation in ritual working groups.) Furthermore, Starhawk argues that any quality that has been assigned to one gender can often be found in its opposite. Therefore, aggression is not a singularly masculine trait. (45) Nevertheless, that there are perceived gender differences is betrayed in Starhawk’s claim that the feminine is the life-giving force while the masculine is the death force. To attain balance the individual must be in touch with both forces. (46) Furthermore, according to Starhawk, to name is not to limit, but to invoke. (47) Therefore, Starhawk argues that the discourse looses its sexism through an understanding that invocation calls upon the masculine and feminine aspects of the Goddess. Acceptance of this notion has important implications for feminist deconstructions of religious traditions. If we follow Starhawk’s claim that to name is not to limit but to invoke, we must also allow for the dual nature of masculine naming practices in Western monotheisms, an issue that feminist scholars of the Bible have struggled against for many years. Scholars such as Phyllis Trible have argued that the imagery surrounding God in the Old Testament is often, and unjustly in its ancient Hebrew context, interpreted in masculine terms. (48) The perspective of Starhawk, that naming practices invoke rather than limit, seems to undercut Trible’s argument by offering some legitimation of these patriarchal images. Goddess worshipers who adopt Starhawk’s approach fail to fully confront the blatantly cruel and warlike aspects of goddesses like Inanna. Instead, some subtly shift the focus from violence to death. As the crone, 43. Ajit Mookerjee, Kali, the Feminine Force (Rochester: Destiny Books, 1988), 54 44. Starhawk, “Witchcraft and Women’s Culture,” 268. 45. Starhawk, The Spiral Dance, 8. 46. Ibid., 41. 47. Christ, Rebirth of the Goddess, 94. 48. For the image of God in the Old Testament, see Phyllis Trible, God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1978). © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004. the Goddess brings death: she is the giver and taker of life. (49) Moreover, death is a good thing: it is part of the great cycle of life. The cycle of life embodies both creation and destruction. However, this is not the senseless destruction of armies drawing blood on battlefields; instead, this is the destruction of violent thunderstorms and floods. Starhawk admits difficulty in thinking of the Goddess as destroyer despite texts such as those cited above that clearly present goddesses like Inanna as cruelly violent. Instead, the wanton violence is given legitimation through an assertion that creation postulates change and change is a destructive process. (50) The more logically consistent perspective argues that Inanna as war goddess is a false representation. This position contends that the war goddess is a result of patriarchal rewrites of the Inanna myth. The purpose of the rewrite was to subjugate Inanna to, and reflect the values of, the new patriarchal pantheon. According to Mary Wakeman, the changeableness of Inanna represents the dawning of the patriarchal consciousness in Sumer (third millennium BCE). Her appearance as the femme fatale expresses fears associated with sexuality, change, and death. (51) The goddesses described in these patriarchal myths are mere reflections of their older selves. (52) The loving, protecting, nurturing, fertile Inanna is the older and more genuine understanding of the Goddess. Images of an armed and fighting Inanna reflect her transformation in the patriarchal pantheon. (53) We must note, however, that the so-called patriarchal revolution of the third millennium BCE is hardly a settled issue. Taking their cue from Gimbutas, many scholars of ancient Goddess culture argue for violent invasions of Indo-European hordes descending from the steppes of central Asia upon peaceful matriarchal cultures. However, archaeologists have found little evidence that the necessary conditions existed in the fourth millennium BCE to initiate migrations of entire population groups (.54) Furthermore, it seems apparent that violent invasion theories simply ignore alternate theories of “peaceful transfer of languages,” social interaction, or peaceful disintegration as processes for societal change. (55) Superficially, the argument for two Inannas (matrifocal and patrifocal) is persuasive. Ultimately, however, it may improvable. The hymns of Enheduanna to Inanna are among the earliest recovered. We can date Enheduanna through the reign of her father Sargon (2340–2284 BCE). 49. Trible, 8. 50. Starhawk, The Spiral Dance, 94. 51. Wakeman, 19. 52. Christ, Rebirth of the Goddess, 68. 53. Ibid., 97. 54. Eller, 164. 55. Ibid., 163-165. © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004. Moreover, it is difficult to argue that Enheduanna, an Akkadian herself, created an understanding of Inanna that was alien to Sumerian culture. Clearly, whatever image of Inanna Enheduanna chose to present must have corresponded in many ways to the images of Inanna that existed in the culture at large. If not, it becomes incomprehensible that these images were accepted, and even revered, by the Sumerians. Ultimately, the reappropriation of Inanna into Goddess religion is a modern quest for female empowerment. It is, moreover, a process fraught with anachronism (out of its proper or chronological order). According to Mary Wakeman, the women’s movement has taken an interest in ancient Sumer as part of a female desire for empowerment and a new myth of origins. (56) Wakeman describes the reaching back to Sumer as a process of “reaching behind the intervening patriarchal development to recover our sense of connectedness to the earth, with other species, with each other and with our own bodies.” (57) However, there is little evidence that a sense of “connectedness with the earth” is recoverable in ancient Mesopotamian narrative. Concepts like “connectedness with the earth” are philosophies that arise from modern ecological movements. It is a mode of thinking that is particular to our culture and our historical context. There is little evidence the Mesopotamians viewed the earth in this manner. In fact, there is a substantial body of evidence that seems to indicate that the Mesopotamians viewed nature from a position of subjection and fear. (58) As noted above, some Goddess theologians locate female power in biology. That this has been an important issue in Goddess religion is reflected in the continued and sustained focus upon the role of the ancient Goddess in creative and fertile endeavors. Carol Christ argues that the female body is an important metaphor for the creative powers of the earth body. (59) Moreover, “it will not help women to pretend that giving birth and nurturing children are not important in our lives.” (60) Z. Budapest claims that the female ability to give birth is a biological connection and manifestation of the Goddess. (61) Elinor Gadon argues further that, “Women experience power as rooted in their biological selves, an enabling 56. Wakeman, 7. 57. Ibid., 25. 58. Thorkild Jacobsen, “Mesopotamia,” in The Intellectual Adventure of Ancient Man: An Essay on Speculative Thought in the Ancient Near East, ed. H. Frankfort et al. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1946; city?: Phoenix Books, 1977), 125-83. 59. Christ, Rebirth of the Goddess, 91. 60. Ibid., 92. 61. Z. Budapest, “Self-Blessing Ritual,” in Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion, ed. Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1979), 271. © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004. life force in contrast to the authoritative, hierarchical ‘power over’ now so widely intrusive in our society.” (62) These statements raise a host of questions. Is nurturing biological or is it culturally conditioned? Some scholars have proposed that children in the Middle Ages were thought of as little adults and were treated accordingly, even by their mothers. (63) If correct, this thesis supports the argument that many characteristics associated with nurturing are culturally conditioned. If this is indeed the case, we cannot accept that the discourse about the nurturing Goddess is rooted in biology and nature. If there is a natural desire to give birth and nurture children, how do we understand women who choose not to have children? Are they biologically abnormal? Are they somehow less nurturing? Are they somehow less than natural? One might further ask whether childbirth was always a welcome event. (64) We know that in the past giving birth was dangerous for the mother and the child. Thus, one must consider if our modern perspective of safe childbirth is a further anachronism through which past female experiences of childbirth are being viewed. Judith Ochshorn recognizes the problems with these assumptions. She argues, “Fixing the distant origins of the Great Goddess worship in the females’ ability to reproduce is biological reductionism at its most pernicious.” (65) Indeed, she further claims, the veneration of maternity sounds suspiciously like a male invention used to focus female attention on their proper role in life (66) An unstated assumption in this discourse is that the masculine is less nurturing, while the feminine role in fertility and nurturance is primary. It seems reductionist to claim that the male as nurturer is simply another example of patriarchal subversions of what properly belongs to the female. If there is a natural dichotomy between the nurturing roles of males and females, then the medieval veneration of Jesus as breasted mother, (67) or even the rising modern practice of males rearing children while the female pursues a career, become biologically and naturally contradictory. Interestingly enough, if Sherry Ortner is correct, identifying the feminine and the Goddess with nature plays into the “universal” second (62). Elinor W. Gadon, The Once and Future Goddess: A Symbol for our Time (New York: Harper and Row, 1989), 230. 63. Philippe Ariès, Centuries of Childhood: A Social History of Family Life, trans. Robert Baldick (New York: Knopf, 1962). 64. Ochshorn, 388. 65. Ibid., 387. 66. Ibid. 67. Caroline Walker Bynum, Jesus as Mother: Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982), 113-25. © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004. class status of women. Ortner postulates that over the course of history the female has been identified and associated with nature while the masculine is identified with culture. “Since it is always culture’s project to subsume and transcend nature,” this perspective facilitates the tendency to subordinate and oppress women. (68) Ortner touches upon something very important with this statement. Following Peter Berger, not only does this association of the female with nature and the masculine with culture allow for the subjugation of women, it also creates a legitimation of a constructed social order. (69) The association of the female with nature, as something outside culture, is a very effective legitimation that hides the socially constructed nature of these gendered roles. Too often we mistake gender roles—socially constructed perceptions of maleness and femaleness based upon sex—with sex, the biologically determined differences between male and female. Many of the characteristics assigned to the great Goddess and re-created in Goddess worship are manifestations of the many ways that humanity has imagined the differences between manliness and femininity. This is not to say that biology is unimportant, however; what is important for Goddess reconstructions is the significance given to sex in “culturally defined value systems.” (70) In the words of Sherry Ortner, The secondary status of woman in society is one of the true universals, a pan-cultural fact. Yet within that universal fact, the specific cultural conceptions and symbolizations of woman are extraordinarily diverse and even mutually contradictory.(71) Specifically, Ortner continues, even if we “postulate emotionality and irrationality, we are confronted with those traditions in various parts of the world in which women functionally are…more practical, pragmatic, and this-worldly than men.” (72) The fixing of gendered modes of thought and experience is evident in reports of how men and women experience the Goddess. Female testimonies of Goddess experiences are dominated by mystical and “feminine” imagery, including birth canals, rebirth, enfolding, and envelopment. (73) On the other hand, Carol Christ describes the experience of the writer 68. Sherry Ortner, Making Gender: The Politics and Erotics of Culture (Boston: Beacon Press, 1996), 27. 69. Peter Berger, The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion (New York: Doubleday, 1967), 3-28. 70. Ortner, 25. 71. Ibid., 21 72. Ibid., 35. 73. Christ, Rebirth of the Goddess, 5-7. © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004. Ralph Metzner, whose experience lacks this imagery. Metzner discovered the Goddess through the work of Gimbutas. His discovery was based upon the realization of a lost history and was the result of an intellectual exercise. (74) The contrasting descriptions of female and male experiences reflect internalized gendered conceptions concerning the way males and females think and experience. Notice that the female experiences the Goddess through feeling, emotion, and mystical experience. The male, on the other hand, plays the role of rational thinker and finds the Goddess through intellect and thought. To conclude that the female approaches the Goddess through emotion while the male approaches the Goddess through rationality buys into a very specific gendered construction. Specifically, that the female is warm, moist, and emotional, while the masculine is rational, cold, and intellectual. Goddess Remembered concludes with a short testimonial by Charlene Spretnak. Spretnak recalls hours spent researching the ancient Goddess and suddenly coming to the realization that what she had found is the “female.” What she was reading was resonating within her and felt correct. Christ’s statement reveals a deeper tension that underlies this creative re-imagination of ancient images. Specifically, in light of this discussion, the question becomes “Does history matter?” Mary Jo Weaver asks, “[W]hen Neopagan practitioners appear satisfied with the Goddess as a psychic reality, must we conclude that they cannot find objective verification of her existence, or that they do not need it?” (75) We propose that, for the reasons outlined above, they do not need objective verification. “Witchcraft, today, is a kaleidoscope of diverse traditions, rituals, theologies, and structures.” (76) According to Starhawk, the outer forms of religion do not matter. What matters is the inner forms that cannot be described or defined but must be felt or intuited. (77) Z. Budapest states that Goddess worship is self-worship and just as the Goddess has thousands of names she can be worshipped in thousands of different ways. (78) According to Christ, “Out of our intuition, experience and research, some of us are creating Goddess traditions anew.” (79) Clearly, historical problems 74. Ibid., 7. 75. Weaver, 50. 76. Starhawk, “Witchcraft and Women’s Culture,” 262-63. 77. Ibid., 262-263, 78. Z. Budapest, “The Vows, Wows, and Joys of the High Priestess or What Do you People Do anyway?” in The Politics of Women’s Spirituality: Essays on the Rise of Spiritual Power within the Feminist Movement, ed. Charlene Spretnak (Garden City, NY: Anchor Press, 1982), 538. 79. Schüssler-Fiorenza, 123. © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004. are being ignored in order to maintain focus upon the psychic reality of Goddess religion for its adherents. (80) These problems manifest themselves in the gendered reappropriation of Inanna. We noted that the characteristics Goddess worshipers choose to represent Inanna serve the gendered theological interests. That certain key aspects of Inanna’s personality are ignored or downplayed is not a problem because the reality of Inanna is created in the imagination and experience of each individual worshiper. Ultimately, for Goddess religion, this “open source” system becomes a built-in protection against the sort of criticisms leveled in this article. However, these same protections may also prevent Goddess worship from becoming a lasting and major force in world religion. Spretnak speaks as if she has discovered some form of femaleness that independently exists in nature just waiting to be recovered. However, one could argue that Spretnak does to the texts what society does to her. In other words, the female Spretnak is finding in the text is the female that she has internalized in the context of the social setting and community revealed in Goddess Remembered. The process of gender construction is evident as the participants discuss and describe their experiences of what the great Goddess is and should be. In this setting the gender construction is affirmed, reinforced, and internalized. Albert Schweitzer’s comments upon the difficulty of the quest for the historical Jesus seem appropriate: “There is no historical task which so reveals a man’s true self as the writing of a life of Jesus.” (81) In other words, we must be self-reflective about what we bring to the texts because, if we are not wary, we are likely to find ourselves in them. Bibliography Ariès, Philippe. Centuries of Childhood: A Social History of Family Life, translated by Robert Baldick. New York: Knopf, 1962. Berger, Peter. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. New York: Doubleday, 1967. Budapest, Z. “Self-Blessing Ritual.” In Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion, edited by Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow, pages? San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1979. Budapest, Z. “The Vows, Wows, and Joys of the High Priestess or What Do you People Do anyway?” In The Politics of Women’s Spirituality: Essays on the Rise of 80. Weaver, 58. 81. Albert Schweitzer, The Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of its Progress from Reimarus to Wrede, with an introduction by James M. Robinson, trans. W. Montgomery (New York: Collier, 1968), 4. © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004. The Pomegranate 6.1 (2004) Spiritual Power within the Feminist Movement, edited by Charlene Spretnak, pages?. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press, 1982. Bynum, Caroline Walker. Jesus as Mother: Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982. Christ, Carol P. Rebirth of the Goddess: Finding Meaning in Feminist Spirituality. New York: Addison-Wesley, 1997. Christ, Carol. “Why Women Need the Goddess.” In Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion, edited by Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow, pages?. San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1979. Condren, Mary. “Women and Goddess Traditions: In Antiquity and Today.” In Goddesses and the Lives of Women, edited by Judith Oschorn, pages? Minneapolis: Fortress, 1997. Cowan, Douglas E. Cyberhenge: Modern Paganism on the World Wide Web. New York: Routledge, forthcoming. Dalley, Stephanie, trans. Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh and Others. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989. Eller, Cynthia. The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory: Why an Invented Past Won’t Give Women a Future. Boston: Beacon Press, 2000. Fiorenza, Elizabeth Schüssler. “Roundtable Discussion: What Are the Sources of my Theology.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 1 (Spring 1985): 122. Gadon, Elinor W. The Once and Future Goddess: A Symbol for our Time. New York: Harper and Row, 1989. Gimbutas, Marija. The Civilization of the Goddess. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1991. Goddess Remembered. Videocassette. Produced by Studio D. city?: National Film Board of Canada, 1989. Jacobsen, Thorkild. “Mesopotamia.” In The Intellectual Adventure of Ancient Man: An Essay on Speculative Thought in the Ancient Near East, edited by H. Frankfort et al., 125-83. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1946; city?: Phoenix Books, 1977. Jacobsen, Thorkild. The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976. Knight, Sirona, and Patricia Telesco. The Cyber Spellbook: Magick in the Virtual World. Franklin Lakes, State?: The Career Press, 2002. Kramer, S. N., trans. “Hymnal Prayer of Enheduanna: The Adoration of Inanna of Ur.” In The Ancient Near East, vol. 2, A New Anthology of Texts and Pictures, edited by James B. Pritchard, pages? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975. Neuman, Eric. The Great Mother, An Analysis of the Archetype, translated by Ralph Manheim. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1963. Ortner, Sherry. Making Gender: The Politics and Erotics of Culture. Boston: Beacon Press, 1996. Raphael, Melissa. “Truth in Flux: Goddess Feminism as a Late Modern Religion.” Religion 26 (July 1996): 200. ReWeaving. “In Praise of Inanna.” http://www.reweaving.org/inanna.html (accessed February 7, 2004). Schweitzer, Albert. The Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of its Progress from Reimarus to Wrede, with an introduction by James M. Robinson, translated by W. Montgomery. New York: Collier, 1968. Spiral Goddess Grove. “Goddess Altar of Ishtar and Inanna.” http://www © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004. Thomas Re-Imaging Innana .spiralgoddess.com/Inanna.html (accessed February 7, 2004). Starhawk. “Witchcraft and Women’s Culture.” In Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion, edited by Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow, pages? San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1979. Starhawk. The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess. 10th ed. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1989. Stephens, Ferris J., trans. “Prayer of Lamenation to Ishtar.” In Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, edited by James B. Pritchard, pages?. 2nd ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1955. Stone, Merlin. When God Was a Woman. San Diego: Harcourt Brace and Company, 1976. Telesco, Patricia. 365 Goddess: Daily Guide to the Magic and Inspiration of the Goddess. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1998. Trible, Phyllis. God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1978. Wakeman, Mary. “Ancient Sumer and the Women’s Movement: The Process of Reaching Behind, Encompassing and Going Beyond.” The Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 1 (Fall 1985): 8. Weaver, Mary Jo. “Who Is the Goddess and Where Does she Get us?” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 5 (Spring 1989): 59. Wolkstein, Diane, and Samuel Noah Kramer, trans. Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer. New York: Harper and Row, 1983. © Equinox Publishing Ltd 2004.