Diversity Reference Manual - Center for Development of Human

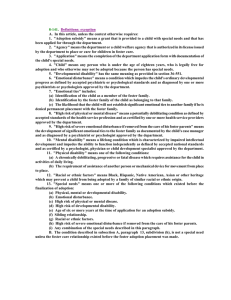

advertisement