Booworwa River Recovery

advertisement

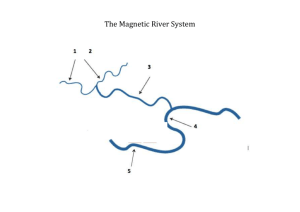

Boorowa River Recovery – Our River Sue Streatfield, Greening Australia South East NSW 2005 1. Overview of the River o The Boorowa River Catchment is located in the headwaters of the Lachlan River in central western NSW o The river runs from south to north and joins the Lachlan River just below the main water storage facility of Wyangala Dam. o The catchment covers an area of app 182,000 ha and the river length is an estimated 150 kms o The Boorowa River in the Lachlan catchment is an important part of the Murray Darling Basin. o Large amounts of salt discharge daily into the Lachlan River from the Boorowa River, thus impacting on the water quality of downstream users. o On average, approximately 26 t/day of salt discharge from the Boorowa River into the Lachlan River at Cowra. o The Boorowa River catchment has been extensively cleared for agriculture during the past 150 years. It is now estimated that less than 10% of the catchment remains under woodland or forest cover (Freudenberger et al 2004). 2. How the River interacts with the community History o The local area was originally inhabited by the Wiradjuri tribe - largest in NSW . o The Wiradjuri lands stretch from Nyngan to Albury and from Hay to Bathurst - the largest territory in New South Wales. o The rivers were important routes for Aboriginal people, providing food, water and shelter. o The Wiradjuri had semi permanent camping spots on the Boorowa and Lachlan Rivers. o There may have been several thousand of the Lachlan tribal group at first settlement, but surveys showed only 300 were left in 1851. o The name Burrowa, by which the region was once known, and Boorowa were said to be aboriginal words for native birds – bustard or plains turkey which were once common but now long since gone. o The region was first settled by Europeans in the later 1820s, especially by Irish convicts transported from Clonoulty, County Tipperary after political activity in 1815. o By 1871, the Burrowa Police District alone had 3,865 residents, a combination of Free Selectors and miners. In 1995, the population in the Shire was 2,630, whereas in 2001, the population was 2,321, with 1,184 males and 1,137 females. About 1,300 people live within the Boorowa township area. o The name of the district was changed to Boorowa in the mid 1900s (Lyold, 1990). o Boorowa, on the banks of the Boorowa River, grew in the middle part of the 19th century as a service centre for rural activities, providing a focus for the region. Its shops and pubs were often fiercely Irish in their outlook. o Boorowa retained a strong sense of its Irish roots although the convict backgrounds of its original settlers were soon forgotten. o By 1851 there were less than 3000 people in the entire Lachlan district o The main occupation of Boorowa settlers was wool. There were already tens of thousands of sheep in the district by 1840. With fencing and improved techniques Boorowa flourished as a prime sheep growing region - shipping wool, meat and (in the 1990s) live ship to world markets. o The village of Boorowa was surveyed around a main crossing of the Boorowa River and gazetted in 1850. On Crown Land and with sections reserved for the infrastructure of a town - court house (originally 1860 present building 1884 - closed 1988), post office (first 1856 - today's 1876) , and pound, it replaced earlier private towns. o In the early days Boorowa was notorious for crime and lawlessness. Robberies, assault and stock stealing were rife - fuelled by ex-convicts, poor immigrants from the U.K. with little respect for authority, and of course, bushrangers. o Although isolated in early days, Boorowa had a rich social and sporting life - Lessons were held in the local swimming hole on the river from 1920 until a proper swimming pool was built in 1965. o Economic Importance o Grazing is the dominant activity in the region, with some cropping on the more productive soil types. o The majority of people are employed in agricultural industries, directly on farms o Reticulated (tap) water is supplied to the Boorowa township from a weir on the Boorowa River. Fifty per cent of the urban population is connected to reticulated water and 50% of the rural population uses non-reticulated water. o The Boorowa River contributes a substantial volume of water and salt load to the Lachlan River, and is an important source of water to communities and irrigators downstream of the confluence with the Lachlan River. Fauna and Flora Past extensive clearing has resulted in significant loss of natural habitat for native plants and animals, species occurring in vegetation remnants within or near the shire provide some indication of the area's former native species diversity Does the river provide drinking water – for how many people o The major towns dependant on the Lachlan River for water supplies are Cowra, Forbes, Condoblin, and Lake Cargelligo. There are also a number of smaller towns and villages dependent on the river (Beumer, 2001). The problems affecting the River Environmental issues such as land and water degradation are complex and often interrelated. The main environmental issues that affect the Boorowa Catchment are: Native vegetation and biodiversity decline Dryland salinity Soil acidity, erosion and soil structure decline Water quality decline Downstream water users from the Boorowa Catchment are also affected due to declining water quality in the Lachlan River, as the result of salt and sediment load from the Catchment. Loss of vegetation o Although land clearing for agriculture and grazing started during the initial settlement in the 19th century, the greatest clearing activity is thought to have been during the 1920s. o The Boorowa River catchment has been extensively cleared for agriculture during the past 150 years. It is now estimated that less than 10% of the catchment remains under woodland or forest cover (Freudenberger et al 2004). o Prior to European settlement, Eucalypt species dominated and characterised the native vegetation of the region. Almost all native communities appear to have been cleared or modified to some extent by agriculture or grazing (Yates and Hobbs, 1997). o Pre-clearing extent o Riparian forests of Red Gum or She Oak occurred along the rivers and major creeks. Woodland communities, dominated by Blakely’s Red Gum and Yellow Box, occur along most creek lines and lower slopes. A Red Stringy-bark – Long Leaved Box forest occurs on sedimentary rocks on the lower slopes in the south-east of the Shire. White Box woodlands with a grassy understorey formerly occupied most of the undulating slopes in the Shire, while a grassland/open woodland occupied much of the broad basin centred on Boorowa. Ridge-lines and upper slopes support dry forest in which Red Stringy-bark is always a dominant species. Name of Vegetation Ecosystem River Red Gum forest River Oak riparian forest Pre-1750 Area (ha) Existing Area (ha) % Cleared 3,063 577 81% 738 111 85% Blakely’s Red Gum – Yellow Box Woodland 50,071 4,093 94% Kangaroo Grass – Red Leg grassland/open woodland 24,269 418 98% White Box Woodlands 39,700 2,204 96% Red Stringybark/Long-leaved Box/Candlebark Open Forest/Woodland 17,297 2,197 87% 2,379 828 65% Red Stringybark Dry Shrub Forests 72,955 9,492 87% Red Stringybark -Joycea grass tussock open forest 47,205 8,965 81% 257,659 28,862 88% Callitris endlicheri-Red Stringybark-Red Box shrub forest TOTAL o Much of the existing cover is in separate patches (remnants) and affected by long-term continuous grazing o Understorey is non-existent in most areas; particularly those used for the grazing of stock. These patches have been categorised as “disturbance evident, some regeneration” to “severely degraded, no regeneration”. o The majority of native vegetation is restricted to ungrazed roadsides and reserves. The vegetation of Boorowa is highly fragmented and dysfunctional. o The remaining remnants are under considerable stress from increased salinity, over fertilisation, grazing, herbicide drift and soil compaction. o Remaining vegetation continues to decline due to fragmentation, isolation and natural senescence. o The perilous state of the Shire’s vegetation means that its retention, regeneration and rehabilitation on private land are crucial to its survival Fauna and Flora o Given the extent of vegetation clearing, it is not surprising that many threatened plant and animal species occur within the Catchment. o The habitat for most of the threatened species is predominantly woodland. o The most threatened vegetation communities are White Box woodland, Blakely’s Red Gum – Yellow Box woodland and Kangaroo Grass – Red Leg grassland/open woodland communities are listed below. o A recent survey in the Catchment by CSIRO (Freudenberger, 2001) reported that “The Boorowa River catchment in not a biological desert. It may only have 7% cover of remnant woodland, but 115 species of birds were recorded across a diversity of woodland types, remnant sizes and habitat structures within the catchment.” The following (Table 11) is a list of threatened fauna in the Boorowa Shire. Common Name Species Status in Catchment area Birds Bush Stone Curlew Burhinus gralarius Superb Parrot Polytelis swainsonii Swift Parrot Lathamus discolor Barking Owl Ninox connivens Speckled Warbler Cthonichola saggitata Hooded Robin Melanodryas cuculatus Black-chinned Honeyeater Melithreptis brevisrostis Painted Honeyeater Grantiella picta Regent Honeyeater Xanthomyza phrygia Grey-crowned Babbler Brown Treecreeper Diamond Firetail Finch Pomatostomus temporalis Climacteris picumnus victoriae Stagonopleura guttata Extremely Rare; southern part of its range Adopted as a symbol of the Boorowa region Autumn/winter visitor, feeds on Whitebox & Red Ironbark Rare, southern part of its range Recorded in several sites Few sightings, inhabits grasslands & woodlands Rare, although reported in several sites No formal sightings, feeds on Mistletoe species No formal sightings, Inhabits BoxIronbark woodlands Several families in region, inhabits gassy woodlands Recorded in several sites, requires large remnants of native vegetation for survival Rare, Inhabits grasslands and woodlands Mammals Squirrel Glider Petaurus norfolcensis Koala Phascolarctos cinereus Large-footed Myotis Bat Myotis adversus Common Name Species Rare, southern part of its range Few sightings, inhabits woodlands & forests in east Rare, western part of its range, inhabits riparian zones Status in Catchment area Insects Golden Sun Moth Synemon plana Perunga Grasshopper Perunga ochracea Recorded in several Travelling Stock Reserves Rare, restricted to grasslands/open woodlands Table 11 Threatened fauna in the Catchment area (from Priday et al., 2002) Salinity o The large tract of mostly treeless land around Boorowa faces serious salinity and salt load in waterways over the next 50 years. o On wet days the Boorowa River, which meanders through thousands of hectares of prime sheep and wheat country between Yass and Cowra, dumps 60,000 tonnes of salt into the Lachlan River. o The salt is run-off from farms in the Boorowa catchment which, like much of Australia's prime agricultural land,is being poisoned by salt carried to the surface by vegetation clearing and rising water tables. The area affected by salinity is expanding by 17 per cent each year. o Increasing salinity (salt concentration) of the river could have a major economic impact on domestic and industrial users of water mainly through accelerating the depreciation of capital items. o Urban salinity has been identified in over 80 towns throughout Australia. Salinity in towns is the result of a combination of dryland salinity processes and over irrigation of urban areas. Irrigation of lawns and gardens on permeable soil types that overlie saline material mobilise salts, and groundwater flow redistributes these salts down slope. Towns are often located in low points in the landscape, and are adding water to those landscapes (Wooldridge, 1999). The Boorowa Township has obvious symptoms of salinity, such as: o dying and dead trees o salt tolerant species of grass appearing in gardens and playing fields, especially couch grass o bare patches in lawns and playing fields, often with white crusting on the surface o cracked, broken and deteriorating concrete paths and gutters o road surfaces breaking up o rising damp in building – private and public o deterioration (fretting) of bricks and mortar o salt crusting on brickwork, concrete and pavers o deterioration of house foundations o corrosion of underground services, such as gas and water pipes, sewerage systems etc. A recent survey of the Township revealed that at least 25 houses (or about 5% of houses in the Township) were currently displaying some damage from high saline watertables (Ivey ATP and Wilson Land Management Services, 2000). Damage to infrastructure can be costly to repair and can affect property values. Erosion o About 30% of the drainage network in the Catchment shows signs of streambank or gully erosion. The total length of drainage lines is 4,637 km Gully erosion has been recorded on 1,537 km. o Water quality has been severely impacted on, with the Boorowa River and Hovell’s Creek ranking second in a study on the intensity of gully erosion across the Lachlan Catchment (Brown, 1988). Water Quality o Turbidity and nutrient load, like salinity, are critical water quality issues in Catchment. They have become problems because of the uses to which the Catchment has been put since European settlement and because their levels have been significantly increased. o Turbidity is a natural phenomenon and has long been a feature of the district, but past and some current land management practices, have exacerbated it. As with salinity, turbidity is strongly influenced by river flows and runoff from the land. o Erosion due to landuse practices has greatly impacted on turbidity as soil erosion has increased. This increased turbidity is likely to be associated with erosion within the catchment. o A major source of sediment, nutrients and faecal (microbiological) contamination in our waterways is derived from stock camps and watering points along or creeks and rivers. Pests and Weeds Addressing problems o In order to limit erosion and the movement of sediment to the rivers, it is important to maintain a vegetative cover on land and to keep livestock away from riverbanks. Fencing stock out, to reduce traffic on creek and river banks, and providing alternative watering points (troughs, or safe bank access) is a viable solution in most cases. – River recovery will undertake these actions. o Through GA River Recovery will work closely with the Lachlan CMA, Transgrid the Boorowa community to achieve a whole-of-reach riparian restoration project on the Boorowa River and its tributaries by targeting willow removal, revegetation of riparian area and increasing connectivity of adjacent native vegetation over a 100km section of the river and its tributaries. o The project will target an area large enough to make a difference to the water quality and biodiversity of the Boorowa region o Importantly, the project will build on the past successful activities undertaken by the community Through the Saltshaker project, GA has already worked with 78 landholders on 80 different properties, the project and revegetated 930 hectares (ha) more than doubling the area of tree cover in the project zone. o Dept of Primary Industries (NSW Fisheries) will further improve aquatic biodiversity and water quality through the re-introduction of native species, such as the Purple Spotted Gudgeon, into treated areas of the river. Media Article "Flagship river" for hotspot Boorowa Friday, 12 August 2005 Boorowa News Greening Australia has c hosen the Boorowa River as a "flagship river" in an Australia-wide river recovery project. Other "flagship rivers" chosen include the Murray, the Yarra, the Hawkesbury Nepean and the Derwent in the project that aims to rehabilitate the health of rivers across the nation. In a surprise announcement at the launch of the Boorowa Catchment Action Plan on Monday last week, Lori Gould from Greening Australia told of the project and the money that had been contributed. "The reason we went with the Boorowa River as our flagship river is that Boorowa is a hotspot for salt," said Ms Gould, a project manager with Greening Australia (ACT and South East NSW). "It puts salt into the Lachlan which is a major contributor of salt to the Murray Darling basin. We thought we could achieve something by homing in on a hotspot We thought we could actually make a difference. "And we have a rapport with the local community. It seems the community is accepting of it because we got some great feedback on Monday." Ms Gould said the aim of the recovery project on the Boorowa River and its tributaries was to improve water quality and reduce salinity," she said. "We are now developing ways of running it based on a past project that was very successful, Salt Shaker. "We liked the fact Salt Shaker was community driven, it was flexible and adaptive, based on a scientific approach and it used incentives. We want to ensure this new project is run at a community level instead of a top down approach." Greening Australia has already pledged $100,000 to the project, with half of that coming from the National Heritage Trust. Transgrid has given another $25,000. But there was more exciting news on the night, when Rob Gledhill, chairman of the Lachlan Catchment Management Authority (CAN) rose to speak. He told both Lori Gould and the audience that, if the community endorsed the plan, the Lachlan CMA had pledged a further half a million dollars to it. As mayor of Boorowa Council he reminded people that the council had put close to $40,000 into the Saltshaker project. "It would not have got off the ground otherwise," he said. "If the community gets behind this one, we will put dollars towards it." So partners in the project now include Boorowa Council, Greening Australian, the Boorowa Regional Catchment Committee and the Lachlan CMA. "It's a potentially huge project," said Ms Gould. "We certainly got a lot of support from Monday night's meeting. "We wanted to get the community involved from the very start because SaltShaker was so successful. We felt we wanted to replicate that." She said there was "a pretty big toolbox of options" to give rivers and creeks the ability to withstand the pressures they face. These include "putting in a buffer zone to intercept surface salt, fencing off stock, reducing erosion and sedimentation and revegetation". Cleaning up fish habitats and restocking native fish is also part of the plan.