THE ONTOLOGICAL ARGUMENT

advertisement

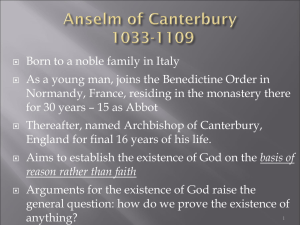

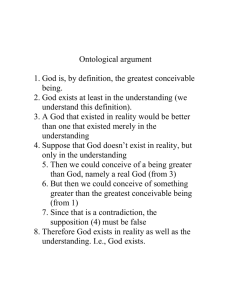

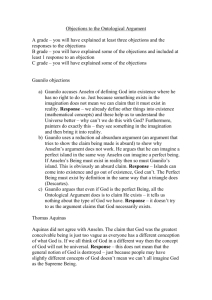

The Ontological Argument: Revision notes THE ONTOLOGICAL ARGUMENT Attributed to St Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury in the 11th century. Attempts to prove that God is a necessary being with every positive attribute: infinitely powerful, wise and good. There is still much interest in it in modern times. THE ESSENCE OF THE ARGUMENT Anselm defines God as a being greater than which nothing can be thought. By 'greater' he meant 'more perfect'. However, if the object of this idea only existed in our mind, we could frame an idea of something superior to it. This being would be a being with all the perfections of the idea we had framed, but with the improvement of actually existing in reality. It therefore follows according to this argument that God must exist in reality: the concept of a most perfect being that we have must include real existence. Any conceptualisation of a being greater than which nothing can be thought must include real existence as one of its qualities: existence belongs to the nature of the most perfect being. GAUNILON'S OBJECTION 1 The Ontological Argument: Revision notes 2 Gaunilon was a monk at Marmoutiers in France, and a contemporary of Anselm's. He was the first important critic of the ontological argument. In his introduction of the ontological argument, Anselm referred to the psalmist's 'fool' who says in his heart, 'There is no God.' Anselm believed that even a fool would have the idea of the greatest possible conceivable being. Gaunilon therefore entitled his objection On Behalf of the Fool. He claims that Anselm's reasoning would lead to absurdities if applied in other areas. Gaunilon develops a parallel ontological argument for the existence of the most perfect island. The argument can be made that, unless it also exists in reality, the island cannot be the most perfect conceivable. We could therefore use the ontological argument to prove the real existence of the perfect island. ANSELM'S REPLY TO GAUNILON Anselm said that the ontological argument could only be applied to God. The important concept for the argument to work is necessary existence. Anselm stated that we could easily imagine an island not existing because it is just a material object and forms part of the contingent world. The Ontological Argument: Revision notes 3 Contrasted with this, God as an infinitely perfect being would not be limited by space or time. He therefore could not be conceived of as coming into existence at a particular point in time, or ceasing to exist at a particular point in time. According to Anselm, this renders his non-existence impossible. As He is perfect, God would not only have to exist, but also have to exist necessarily. NORMAN MALCOLM AND NECESSARY EXISTENCE Norman Malcolm thought that existence is not a predicate. However, he thought that necessary existence is a predicate. An object that exists necessarily depends for its existence on nothing outside itself. Malcolm argues that if we say God exists necessarily, we vastly add to his powers. DESCARTES' REFORMULATION The French philosopher Descartes (1596-1650) reformulated the ontological argument. He treats existence as a predicate: Descartes believed that saying about something that it 'exists' describes a characteristic. He thought that existence must be a necessary characteristic of a perfect being: a defining property The Ontological Argument: Revision notes 4 of God. It is an essential attribute, without which God would not be perfect. So Descartes thought that the idea of existence belongs analytically to the concept of God. KANT'S OBJECTION Kant thought that saying about something that it 'exists' does not add anything in thought to the concept. All that is added by saying that a concept 'exists' is that it is instantiated: that there is something in the world that corresponds to it. Kant accepted that real existence belonged analytically to the concept of God, the most perfect being. However, he asserted that it did not necessarily follow from this that God existed. The most we could say is that, if there is a supremely perfect being, then that being must really exist in order to be supremely perfect. IS EXISTENCE A PREDICATE? Kant expressed this objection formally by saying 'existence is not a true predicate'. In saying about something that it exists, are we actually adding anything at all to the concept of the thing? Or are we instead saying that there is at least one instance in reality of the thing in question? Consider the following argument: The Ontological Argument: Revision notes 5 1) Elephants exist. 2) Dumbo is an elephant. 3) Therefore Dumbo exists. However, when we say 'elephants exist', do we not mean that some elephants exist? This would allow us to say that Dumbo does not happen to exist. DISTINCTION BETWEEN BEING AND EXISTENCE Are we forced to make this distinction? We would then have to say that there are things that do not exist. IS 'EXISTENCE' A PROPERTY, (A PREDICATE)? If God is the greatest being, and existence is a property, then God must exist - otherwise He would not be the greatest being. He would be less good, omnipotent and omniscient if He did not exist, than the perfect being we can imagine. PLANTINGA AND POSSIBLE WORLDS Plantinga presents a version of the ontological argument by using the concept of possible worlds. 'Maximal excellence' = omniscience, omnipotence and moral perfection. It is possible that a maximally excellent being exists. The Ontological Argument: Revision notes 6 There is therefore a possible world in which a maximally excellent being exists. 'Unsurpassable greatness' = 'Maximal excellence in every possible world'. An 'unsurpassably great' being exists either in every possible world or in none. Therefore if any world contains an unsurpassably great being, then every world contains him. However, there is a possible world in which an unsurpassably great being exists. Therefore an unsurpassably great being exists necessarily in all possible worlds. OBJECTIONS TO PLANTINGA This argument assumes that what is necessary or impossible does not vary from world to world. A crucial premise is that maximal greatness, and therefore unsurpassable greatness, are instantiated in a possible world. Leibniz maintained that the ontological argument does not prove God's existence: it just proves that God's existence is either necessary or impossible. THE DEVIL AND THE ONTOLOGICAL ARGUMENT Perhaps Plantinga's methodology could be adapted to prove the non-existence, or the existence, of the Devil. The Ontological Argument: Revision notes 7 The Devil could be defined as a being of 'minimal greatness'. The Devil would possess the ultimate of all negative attributes. If 'non-existence' is regarded as a negative attribute, then this could be attributed to him as well. We would then have to regard 'non-existence' as a predicate, which seems conceptually difficult. We might counter that evil is in fact increased, and not decreased, by the actual existence of the evil being. Perhaps the ontological argument can therefore be used to prove the necessary existence of the Devil, an unsurpassably evil being, rather than his non-existence.