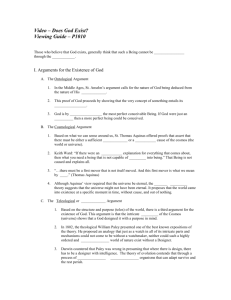

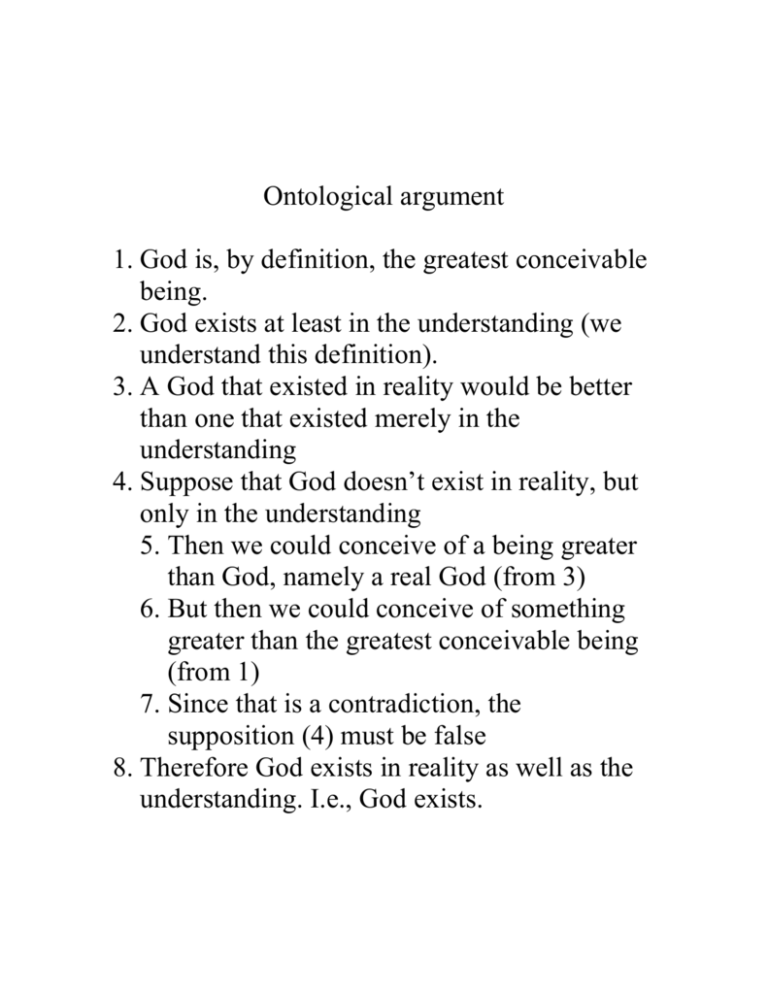

Ontological argument

advertisement

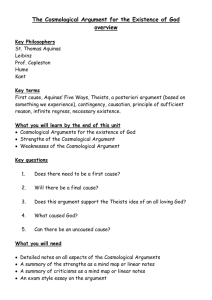

Ontological argument 1. God is, by definition, the greatest conceivable being. 2. God exists at least in the understanding (we understand this definition). 3. A God that existed in reality would be better than one that existed merely in the understanding 4. Suppose that God doesn’t exist in reality, but only in the understanding 5. Then we could conceive of a being greater than God, namely a real God (from 3) 6. But then we could conceive of something greater than the greatest conceivable being (from 1) 7. Since that is a contradiction, the supposition (4) must be false 8. Therefore God exists in reality as well as the understanding. I.e., God exists. Rough idea: existence is an essential part of God’s nature. God couldn’t not exist, any more than a bachelor could be married (and still a bachelor) or a triangle be four-sided. Problems with the ontological argument: Gaunilo’s objection: Something must be wrong, because it “proves” too much: a perfect island Not that anything you can imagine exists, only absolutely perfect things Kant’s objection: Existence is not a predicate (i.e., it is not a quality that changes the nature of something) If existence is not a quality, it cannot be a quality that increases greatness Blackburn’s objection: Real and imagined things are incommensurable Do imaginary turkeys weigh more or less than real ones? Both attack premise 3 Ontological argument is a priori: it relies on reason alone, rather than experience. In this way, like mathematics, unlike science Other arguments are a posteriori: they rely on experience Perhaps the existence of God is like the existence of leptons, quarks. These are things we posit in order to make sense of observations Cosmological Argument: The very existence of the world indicates that God exists Argument from (to) Design: The perfect nature of the world indicates that God exists Cosmological argument 1. Everything that exists has a cause or reason for its existence. (Principle of Sufficient Reason) 2. All worldly beings are dependent beings, i.e., they depend on something else for their existence. 3. Furthermore, the whole chain of worldly beings, even if infinite, is itself a dependent being. 4. There must be something that explains the whole chain. 5. But it cannot be a dependent being, for all of these are already included in the chain. 6. Therefore, there must be a necessary being, i.e., one whose nature explains its own existence. Hume’s objection: God does not seem to be a necessary being. We can imagine God not existing. If God is not necessary, then his existence only pushes things back a small step; it raises more questions than it answers One might reply: “But maybe God is necessary despite his not seeming so” Maybe, but then the same could be said about the world. Our reason for thinking that the world needs something else to explain it applies to God as well: we can conceive of it being otherwise. If that’s a good reason, then the cosmological argument fails, and if it’s a bad reason, then the cosmological argument still fails Argument from (to) Design 1. The world and many of its parts exhibit functional complexity (i.e., certain arrangements of matter are ‘just right’ – a small change and they would no longer perform their functions). Examples: the human eye, pond ecosystems, gravitational constant 2. In this respect, the world is like a giant machine. 3. Like effects have like causes. 4. Machines have intelligent designers 5. Therefore, the world has an intelligent designer Hume’s reply: It’s an argument from analogy, and those are only as strong as the similarities. Does the world really resemble a machine? Does it resemble a perfect machine? Does it resemble a machine more than it resembles a plant? But do we need an intelligent designer to explain how generation gives rise to order? Several known sources of order: Intelligence Instinct Vegetation Generation There is no reason other than human arrogance to elevate intelligence above the others, as the ultimate cause of the rest. In our experience, we see the order going the other way around, generation and vegetation giving rise to intelligence, rather than vice-versa The Problem of Evil Traditional theism: God is All-powerful All-knowing All-good If such a God existed, there would be no evil in the world. But there is; therefore, such a God does not exist Argument can be read probabilistically: perhaps there is an all-powerful, all-loving, all-knowing God, but there is no evidence for that claim and quite a bit against it Free-will defense Evil is the result of human freedom, and a world with human freedom and human suffering is better than a world with neither Blackburn: This only accounts for some of the evils. It is doubtful that earthquakes, plagues, etc. are the result of human free will Perhaps God is “beyond good and evil”, so incomprehensible in his infinity that our human categories can’t apply to Him Blackburn: Then theism is worthless, can’t be a guide to life. The difference between theism, atheism makes no difference