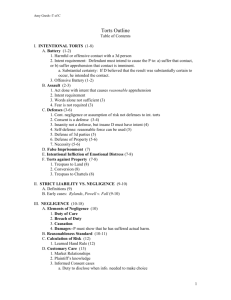

Identifying those Responsible for Harm

advertisement