Tool 4: Design and Administration

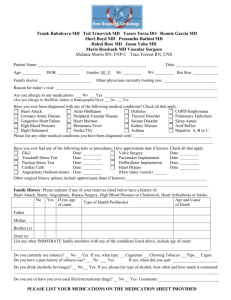

advertisement