Spiritual Dilemmas for the Bereaved by Reverend Richard B

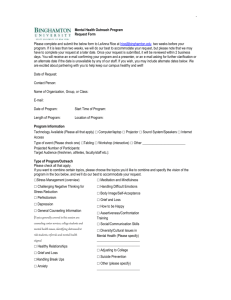

advertisement

Spiritual Dilemmas for the Bereaved by Reverend Richard B. Gilbert My minister spoke glowing words at Dad’s service, but there were problems with Dad and I am not sure I can talk to my minister about this. I believed and I prayed, and still God took my baby away. I don’t want to believe that, but people keep saying that I should feel “blessed” because Jesus chose to take my baby to heaven to be in his heavenly choir. My rabbi sat Shiva with me, but as soon as the “job” was done, he disappeared. I rejoice that Mom is with Dad in heaven. I really believe the wonderful promises of God, but why did she have to suffer so long with cancer, and then Alzheimer’s? There is so much injustice in the world. Why was so much dumped on Mom, and on all of us? I might risk believing in God again, some day, but prayer–– it doesn’t mean anything. In fact, the few times I go to church, I want to shout aloud when the prayer petitions are announced, “Don’t waste your time. God can’t or won’t do anything about your problems!” The above statements are not fiction. They are comments shared with me and others (though many feel forced to keep to themselves) by the bereaved men, women and children who continue to struggle with the issues of life and death, and have often felt everything from frustration to strong resistance in trying to translate the “Why’s” of their sorrow into a meaningful pathway to peace that is a long and personal journey for the bereaved. In a short form of this essay, I will introduce three themes regarding the spiritual dilemmas of the bereaved. Four additional themes focusing on the clergy role in bereavement are not included. Grief is a profoundly spiritual experience, however experienced and expressed by that person In his book, How We Grieve; Relearning the World, Thomas Attig reminds us that the task and opportunity placed before people who experience loss is to embrace the world as it now is because of that loss. He writes, “When someone in our world dies, we remain postured in that world as we were before the death, but we can no longer sustain that posture. We are challenged to learn new ways of feeling, behaving, thinking, expecting, and hoping in the aftermath of loss. As we learn these things, we cope”. (page viii). Grief touches us from top to bottom, reshaping and redefining life as it was, as it feels now (realizing those feelings change faster than the weather) and whatever it will become for us far down the road of this grief journey. Loss has embraced us, and everything about us, and that is true of our spirituality and our religion. First, some basic definitions: Spirituality is something all of us have and are. It may or may not sound particularly reverent or religious, but for the bereaved, the languages and dialects vary but the needs are usually the same. When assaulted by loss we are pressured to find meaning, search for some inner strength when empty seems to be our neighborhood, struggle to find values that bind us as we are tossed to and fro in our sorrow, and a world view that transcends all that we are and experience with something that is eternal or beyond ourselves. Simply put, religion moves beyond the “I” of a person’s spiritual quest, enabling us to find others of similar experience and understanding for mutual care and support. Religion is about rituals, creeds, cultic activities, mission and mutual respect and support. From my book, Heart Peace; Healing Help for Grieving Folks come these words: I am different, Lord I am bereaved. Nothing is the same; everything is different. I feel different. People treat me differently. Loss has been thrust upon me. I may even hold you responsible for that loss. I now must grieve, and I crave a word, a hint of hope and healing. Help me, Lord, to know that you are ever the same, ever constant in my life. Amen. (page 17). Spirituality can be as redefined as life itself when we are grieving. “God so loved the world” may offer a modicum of comfort at the time of a death or funeral, but what does that love represent to a mother and father whose child has just been killed by a drunk driver? What do the words of Christmas, pictures of the Holy Child, and God’s care for children mean to struggling young parents whose child was stillborn? “The Lord is my shepherd” may not be enough for the single mother whose young child, skipping along the debris- laden sidewalk between the projects and the school, and is gunned down by a stray bullet shot from a a gun held by a ten year-old who was meeting the ritual obligations of his or her gang. How might the promises of eternal life spelled out in John’s revelation comfort the recently widowed woman who is terrified of life without her spouse of sixty years? Sometimes it feels like the only option is to give up and die, to be rejoined in heaven. This is where people often struggle in their sorrow, and for many reasons, including their own fear or shame, often suffer in silence. None of us are experts in grief because this loss is always different from previous losses. Most bereaved who seek counsel are in search of clarification. “Tell me I am not crazy!”––and a measure of guidance––“Will you stay with me awhile?” Grief is demanding, it is overwhelming, it is hard work, and, just as no two people grieve alike, we seldom grieve alike for different losses within our own journey. This journey is different because my relationship with this person is different than those of other losses. Grief shatters our foundations, our traditions, and the roots which become the veins through which the gracious love of God flows. Like the hardened arteries of bad dieting or the many forms of heart disease, the veins of grace become blocked by this lack of clarity, by the continued loneliness of feeling abandoned by God and fellow believers. And if our past spiritual resources have been ill-defined, misguided or neglected, the turmoil will be even more pronounced Grief is a powerful filter that can redefine and maybe spoil faith as we know it. It is intriguing that we can understand filters in our body, filters that we use when cooking, and the many filters in our automobiles, but we seem unable to translate this concept to the process we call grief. When we find ourselves in the deepest holes or valleys of the grief experience we experience the raw power and vulnerability of grief. The deeper the pain the deeper the spillover (filtering) into the rest of our story. Thus, we say that grief filters our whole selves, physically, socially, emotionally, sexually, and, yes, spiritually. At the same time, another filtering is going on. These are the filters that influence how we do or do not grieve. Some of those filters are gender, ethnic or cultural expectations, the nature of the loss, past experiences with loss, and, yes, spirituality and religion. Spirituality and religion come with many definitions and personal nuances individually formed and shaped. It also can be well defined, but then compromised by the “packaging” of those providing the care. When a minister thinks or says, “You should be over this (grief) by now”, that is not only ill-timed and manipulative, it is also abusive. Spirituality is meant to be nurturing, enabling and facilitating, not controlling. Guilt is common in grief, emerging from within as we try to give meaning to the events going on in our lives. Shame is not the same as guilt, emerging from external pressures (an abusive parent or spouse, peer pressure, demands of the workplace, and, yes, spirituality and religion). “Jesus died and rose again for your uncle. He is in heaven. Don’t you believe that?” The bereaved now face a dilemma. “How do I say, ‘Yes, I believe, but I miss him so very much? I still don’t want him to be dead.” Because grief is a filter we must ever be mindful of the fact that everything we observe as a griever is manipulated by the profound sense of loss, and the topsy turvy whirlwind of grief. “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death…” (Psalm 23). It is a very lonely and frightening walk through the wilderness we call grief. It is personal, it is long-lasting, it is demanding, and it is a mine field of explosive feelings, detours and disappointments. The Rev. Dr. Richard B. Gilbert, BCC, is the executive director, The World Pastoral Care Center and Director of Chaplaincy Services at Elgin, Illinois. Dr. Gilbert welcomes any opportunity for further dialog. You may contact him directly at dick.gilbert@shermanhospital.org. Visit our website: www.twpcc.org. Printed with permission. Rev. Gilbert wrote this article for our Summer 2002 issue of Wings. ©April 1, 2002