Laryngeal Presentations Of Rhinoscleroma

advertisement

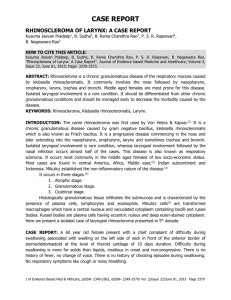

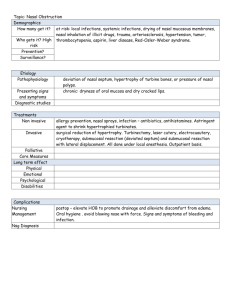

Laryngeal Presentations Of Rhinoscleroma Author 1: Osama G. Abdel-Naby Awad, MD. Otolaryngology, Head and Neck department. Minia University,Minia, Egypt. Author 2: Abdel-Rahiem A. Abdel-Keriem, MD. Otolaryngology, Head and Neck department. Minia University,Minia, Egypt. Author 3: Effat A. Zaki, MD. Speech and phoniatrics unit, Otolaryngology, Head and Neck department. Minia University,Minia, Egypt. Name of author responsible for correspondence and proofs: Osama G. Abdel-Naby Awad, MD. Otolaryngology, Head and Neck department. Minia University,Minia, Egypt. 122 Kornish El-Neel Street, Minia City, Minia, Egypt. Zip code: 61111, Fax: 02-086232505. e-mail : omarsmsm2014@yahoo.com 1 Abstract Background: Rhinoscleroma is a chronic granulomatous disease of the upper respiratory tract caused by Klebesiella rhinoscleromatis. . It is considered endemic in Egypt. The nasal mucosa represents the primary region of occurrence. The disease can potentially spread to involve the larynx and trachea causing dysphonia, stridor and airway obstruction. Objective: To describe the various laryngeal presentations of Rhinoscleroma in our endemic area. Methods: The study included 50 patients with positive histopathological and bacteriological examination for Rhinoscleroma presented with dysphonia and the other manifestations of Rhinoscleroma. Results: 12% only of the patients had the typical subglottic narrowing with sticky greenish disharge and subglottic membrane. Other patients presented with atypical laryngeal presentations e.g. (unhealthy vocal folds, ventricular fold hypertrophy, suproglottic sticky greenish discharge). Conclusion: Rhinoscleroma can present with atypical laryngeal presentations which should be kept in mind to avoid misdiagnosis. Keywords: Rhinoscleroma, Histopathology; Larynx; Hoarseness. 1 Introduction Rhinoscleroma is a chronic, progressive, granulomatous infectious disease of the upper respiratory tract. It was 1st reported in Europe, but it is now rarely diagnosed on that continent. The term RS was 1st coined in 1870 by Von Hebra 1, who described a nasal lesion that they classified as a form of sarcoma. In 1877, Mikulicz 2 described the histological features of this disease in detail and established its non neoplastic inflammatory nature. Von Frisch3 identified the causal agent of this lesion in 1882 as a gram negative coccobacillus, now known as klebesiella rhinoscleromatis. Rhinoscleroma is found predominantly in rural areas and is commoner where socio-economic conditions are poor. Acquisition of the disease is facilitated by crowding, poor hygiene and poor nutrition. Females are more frequently affected than males and disease tends to present in the second and third decades of life. There is also suggestion of iron deficiency may predispose to the disease acquisition.4 Rhinoscleroma affects most areas of the respiratory tract. The nose is affected in (95%-100%) of cases and the pharynx in up to half, other affected areas include the Eustachian tubes,5 sinuses,6 mouth,7 orbit,8 larynx,9 trachea and bronchi.10 The skin in proximity to the affected mucosa e.g. upper lip or nose may be involved and there is a report of back lesions.11 Spread by extension to the brain is also possible.12 In two patients with Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome and Rhinoscleroma, there was no evidence of dissemination despite low CD4 lymphocyte counts.13 The disease usually arises at the junction between epithelial surfaces; for example, in the nose It occurs at the junction between the stratified sequamous epithelium of the anterior nares and the deeper columnar ciliated epithelium. Iron deficiency can lead to sequamous metaplasia and this might be an explanation for the association with poor nutrition and the higher incidence in women of child-bearing 1 age. Rhinoscleroma is divided clinically and pathologically into three stages: atrophic, granulomatous and sclerotic. In the atrophic stage (sometimes called ozaena), there is foul-smelling purulent nasal discharge which persists for months. There may be unilateral or bilateral nasal obstruction, the mucosa may be atrophic. In the granulomatous stage, the patient complains of epistaxis and other problems depending on the other areas affected, e.g. hoarseness with laryngeal involvement. Nasopharynx and pharynx are involved in most of cases which present with shrunken and deformed "Gothic palate" and nasopharyngeal stenosis. Most cases are diagnosed in this stage, when the lesion appears as a bluish-red rubbery granuloma, indurated granulomatous mass. In the fibrotic stage there is nasal deformity and may be destruction of the bone.9 On histological examination there may be atrophy or hyperplasia, although the latter is more common.7 The hyperplasia is termed pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia and contains an infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells, monocytes, lymphocytes and histiocytes (macrophages) with numerous vacuoles containing viable or non-viable bacteria known as (Mikulicz cells) which can be found beneath the basal lamina together with Russell bodies which are eosinophillic structures within the cytoplasm of plasma cells. In the sclerotic stage there is increasing deformity and stenosis, with granulomatous areas surrounded by fibrotic tissue. At this stage Russell bodies and Mikulicz cells are diificult to demonstrate.2,9,14, Rhinoscleroma of the larynx is uncommon and usually occurs in the subglottic region, with the major deleterious effect is the airway obstruction which usually requires endoscopic treatment.15 The aim of this study was to describe the laryngeal presentations in patients with clinically diagnosed Rhinoscleroma in our endemic area 1 during the daily practice. 1 Materials and methods Our prospective study included 50 patients presented to our otolaryngology department, Minia University hospital, Minia, Egypt, from Jan.2103 to Jan.2014. These patients presented with various clinical manifestations of RS. Over the study period, 85 patients were presented to our outpatient clinic with manifestations of Rhinoscleroma in our highly endemic area. We selected only those 50 patients who had dysphonia as their main concern. All patients were subjected to full history taking, with special emphasis on contact with diseased relatives, the duration of their main complaint, other nasal, pharyngeal or laryngeal symptoms, the history of previous medications, the history of previous head and neck operations, history of gastro-esophageal reflux disease, history of common causes of immunodeficiency such as human immunodeficiency virus, long term steroid therapy, diabetes mellitus, or history of immunosuppressive therapy. Thorough otorhinolaryngeal examination was done for all the patients including nasal endoscopic examination. Biopsies were taken from each nasal cavity separately from the muco-cutaneous junction under local anesthesia for histopathological and microbiological examination. Each patient had computed tomography (CT) scan for the neck region. For each patient fibroscopic laryngeal examination was done followed by endoscopic examination of the upper respiratory tract under general anesthesia and other biopsies were taken from any suspected unhealthy lesions in the larynx, these biopsies were also examined histologically and bacteriogically. The bacteriological evaluation was done through culture in MacConky agar and bacteriological identification by using gram staining. The pathological examination of the biopsies 1 was done by light microscope. We considered Rhinoscleroma as a definite diagnosis with the presence of positive bacteriological culture of the klebesiella Rhinoscleromatis and the typical histopathological picture in the form of pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia with an infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells, monocytes, lymphocytes, Mikulicz cells and Russell bodies, with no pathological evidence of malignancy. These requirements of diagnosis was a must for both the nasal and laryngeal biopsies. In addition, laboratory screening for diabetes mellitus, Human immunodeficiency virus infection, complete blood count and routine pre-anesthetic assessment were performed for all patients. Patients in the study received intermittent medications in the form of variable antibiotics (Rifampicin, streptomycin and ciprofloxacin), alkaline nasal douching and multivitamins for short duration ranged from 1 to 6 weeks before the inclusion in the study. We excluded from the study patients with negative nasal or laryngeal bacteriological cultures or with atypical histopathological results, even if the patient had the characteristic clinical manifestations of Rhinoscleroma. Also we excluded patients with gastro-esophageal reflux disease and patients with previous nasal or laryngeal surgeries. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Minia University. Because the study involved no deviation from existing standard therapy for these patients and no new drugs, individual consent was not required by the board. Statistical analysis was done using the Statistical Package for the Social Science software programe (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). 1 Results and analysis Our study included 50 patients including 17 (34%) male patients and 33 (66%) female patients, their ages ranged from 14-48 years old, with mean age 33 years. Fifteen patients (30%) were farmers, 30 patients (60%) were house wives, 3 patients (6%) were students and 2 patients (4%) were drivers. Forty eight patients (96%) live in rural areas and 2 patients (4%) live in urban areas. Ten patients (20%) were cigarette smokers, 8 patients (16%) had diabetes mellitus, 48 patients (96%) had microcytic hypochromic anemia with marked iron deficiency. Fifteen patients (30%) had positive family history of Rhinoscleroma in one of their house hold relatives. The duration of the patients complaint ranged from 2 to 10 years with a mean about 4 years. The duration of dysphonia ranged from 6 to 18 months with a mean about 12 months. Presentation of nasal lesions: All the patients in study had nasal obstruction, 45 patients (90%) had bilateral nasal crustations, 43 patients (85%) had bilateral greenish nasal discharge, 25 patients (50%) had total anosmia, 25 patients (50%) had hyposmia with 5 patients (10 %) had cacosmia. Twenty patients (40%) had epistaxis either unilaterally or bilaterally. We didn't report any patients with atypical nasal manifestations e.g. (nasolacrimal involvement or external swellings). Also we didn't report any patients with primary laryngoscleroma ( i.e. laryngeal manifestations in the absence of nasal lesions). On endoscopic nasal examination the following findings were reported: - Forty three patients (86%) had bilateral roomy nose with thick greenish discharge (atrophic stage). Six patients (12%) had bilateral roomy nose with 1 granular surface (granuomatous stage) and 1 patient (2%) had intranasal adhesions with external nasal deformity (Fibrotic stage). - 20 patients (40%) had pharyngeal involvement with the characteristic shrunken and deformed soft palate "Gothic palate". Presentation of laryngeal lesions: All patients in the study had dysphonia with different grades, 2 patients (4%) had mild to moderate stridor and respiratory distress on exertion. On fibroptic and laryngeal examination under general anesthesia the following findings were reported: - Twenty five patients (50%) had congested and unhealthy vocal folds mucosa with intact focal folds mobility (Fig. 1). - Fourteen patients (28 %) had congested unhealthy vocal folds mucosa with subglottic and suproglottic sticky greenish disharge with intact focal folds mobility (Fig.2). - Five patients (10%) had ventricular fold hypertrophy with irregular unhealthy mucosa with intact focal folds mobility (Fig.3). - Four patients (8%) had subglottic narrowing with sticky greenish disharge (Fig.4). - Tow patients (4%) had subglottic narrowing with thick membrane (Fig.5). These 2 patients were females and had the preoperative stridor and respiratory distress. One of these 2 patients developed more distress during the recovery from the anesthesia which necessitates urgent trachestomy. CT neck findings were consistent with the endoscopic findings. We didn't report any of our patients with tracheal involvement. Table 1 correlates between the nasal stages and the laryngeal findings. 1 Table I. Correlation between the nasal stages, laryngeal findings and duration of dysphonia in the study patients. Laryngeal lesions # of Nasal stage patients congested and unhealthy vocal folds Duration of dysphonia 25 25 patients with atrophic stage. 6-10 months 14 14 patients with atrophic stage. 8-12 months 5 - 4 patients with atrophic stage. 10-15 months mucosa with intact focal folds mobility. congested mucosa unhealthy with vocal folds subglottic and suproglottic sticky greenish disharge with intact focal folds mobility. ventricular fold hypertrophy with irregular unhealthy mucosa with intact -1 patient with granulomatous focal folds mobility. stage. subglottic narrowing with sticky 4 4 patients with graulomatous stage. 10-18 months 2 - 1 patient with graulomatous 12-18 months greenish disharge. Subglottic narrowing with thick membrane and with limited bilateral vocal stage. folds mobility. - 1 patient with sclerotic stage. 1 Fig.1 Congested and unhealthy vocal folds mucosa. Fig.2 Congested unhealthy vocal folds mucosa with subglottic and suproglottic sticky greenish disharge. Fig. 3 Ventricular fold hypertrophy with irregular unhealthy mucosa. 1 Fig. 4 Subglottic narrowing with sticky greenish disharge Fig.5 Subglottic narrowing with thick membrane Discussion Rhinoscleroma is a chronic specific granulomatous disease. The majority of 1 cases affect the upper airways particularly the nose. Rhinoscleroma is one of the most common granulomatous diseases among the Egyptian population. This graulomatous disease occurs sporadically in western Europe usually in immigrant populations arriving from contries where the disease is endemic. The disease is transmitted by air and humans are the only identified host.16 Poor hygiene, malnutrition and crowded living conditions are believed to increase the potential for infection and transmission.17 Patients are immunocompetent except in ineffective phagocytosis by the Mikulicz histocytosis.17-22 The lesions initially start at the muco-cutaneous junction in the nasal vestibule then spread to nasopharynx. The epithelial transition at the subglottic are is the next area of affection.17 The aim of this study was to study the possible laryngeal presentations of Rhinoscleroma. The age of patients in our study ranged from 14-48 years with mean age 33 years, de Pontual 23 found that the median patients age at diagnosis of Rhinoscleroma to be 35.7 years with range from 5-72 years. This wide range can be attributed to the very long contact time needed and the long duration of the complaints, misdiagnosis of many patients by general practioners or non compliance of those poor patients and neglicance of taking medications for long duration.24 In our study, females were affected more significantly than males, this result matches the results of Hart and Rao who suggested the association of Rhinoscleroma with poor nutrition as in rural areas with higher incidence in women of childbearing age.25 Cellular immunity may be impaired in patients with scleroma, however, their humoral immunity is preserved, otherwise patients are immunocompetent in every regard except for the ineffective phagocytosis.17-22 In our study all the patients were immunocompetent by exclusion of the common causes of immunodeficiency such as 1 human immunodeficiency virus infection, history of long term steroids therapy or history of immunosuppressive therapy, except for the presence of diabetes mellitus in 8 patients, which didn't significantly affect the presentation. The duration of patients complained ranged from 2 to10 years , de Pontual et al.23 reported that the probable duration of exposure to klebesiella rhinoscleromatis in endemic areas varied widely from 0 to 28 years and the clinical features and the outcome also varied considerably among cases. Nasal involvement occurred in all the study patients, also the Rhinoscleroma evidence in the larynx in these patients were positive, only 40% of patients had pharyngeal involvement. This important finding in our study opens a new aera in the research of how this scleroma spread through the upper respiratory system. Gamea et al. 26 observed pharyngeal involvement in one third of the cases and mentioned that the nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal scleroma develops as a result of contiguous extension along the palate, lateral wall of nasopharynx and faucial pillars. However, primary involvement of pharynx and larynx has been observed without any demonstrable lesion in nose.23 Only 6 patients (12%) in our study presented with typical presentation of laryngoscleroma in the form of subglottic involvement. Other patients in the study presented with atypical laryngeal involvement, which raised the possibility of other laryngeal diseases, however, the histopathological and bacteriological results for Rhinoscleroma were positive. Razek27 in a recent study addressed the CT findings of laryngo-tracheal scleroma and stated that it appears as symmetrical or asymmetrical circumferential subglottic stenosis with extension into trachea and the bronchi, it may appear as a thickened epiglottis, aryepiglottic fold and vocal cords, and, rarely, there is concentric transglottic narrowing. In our study we didn't report cases with tracheal 1 involvement. In a more recent study, Razek et al.28 used MRI in cases with laryngoscleroma, and they found that laryngoscleroma was seen more commonly in the subglottic, but can occur at the suproglottic region, and they found that laryngoscleroma at granulomatous stage appeared as diffuse circumferential soft tissue mass with high or mixed signal intensity on T2- weighted images, and laryngoscleroma at fibrotic stage was seen as a diffuse asymmetrical circumferential thickening of the subglottic region with low signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Dolci et al.29 in his report revealed that respiratory scleroma affected the larynx in 40%, and the principal findings were glottic and subglottic stenosis. This atypical presentation of scleroma is not confined to the larynx, Fawaz et al.25 reported 18 patients with different atypical presentations of Rhinoscleroma in the form of intraorbital extension, check swelling, Potts puffy tumor, cutaneous involvement and unilateral nasal affection. It was also clear from our study that patients with early nasal stages (atrophic and granulomatous stages) had less severe laryngeal lesions in comparison with patients with late nasal stages ( sclerotic stage) who had advanced laryngeal lesions in the form of subglottic narrowing with thick membrane and respiratory distress. This very important finding also opens a new era for studying the correlation between the nasal and laryngeal stages in a wider range of patients and emphasize on the role of early diagnosis and adequate treatment of this granuloma which may help to prevent a possible serious complications. Our study, up to our knowledge, is the largest series studying patients with laryngeal scleroma and the 1st to correlate between nasal and laryngeal presentations in a hope to alert physians about this important endemic disease. Conclusion 1 From our study, we can conclude that Rhinoscleroma in endemic areas can have atypical laryngeal presentations and the advanced nasal stages are usually accompanied by more affection of the larynx. In order to avoid misdiagnosis and delayed treatment in endemic or non-endemic areas, it is important to keep in mind these atypical manifestations of laryngeal scleroma. Acknowledgments: None. 1 Financial Support : None. Conflict of interest: None Ethical Standards: The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guidelines on human experimentation (Osama Awad) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as reviewed in 2008". And the authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional guides on the care and use of laboratory animals (Osama Awad)." Reference 1 1- Von Hebra F. The clinical and histological findings of Rhinoscleroma (In Germany). Wien Med Wochenschr 1870; 20:1-5 2. MiKulicz J. About The Rhinoscleroma (In Germany). Arch F Klin Chir 1877;20:485-534 3- Von Frish A. The etiology of Rhinoscleroma (In Germany). Wein Med Wochenscher 1882;32:969-82 4- Akhnoukh S, Saad EF. Iron-deficiency in atrophic rhinitis and scleroma. Indian J Med Res 1987;85:576-9 5- Soni NK, Hemani DD. Scleroma of the Eustachian tube: salpingoscleroma. J Laryngol Otol 1994;108:944-6 6- Gamea AM, eL-Tatawi FA. Ethmoidal scleroma: endoscopic diagnosis and treatment. J Laryngol Otol 1992;106:807-9 7. Garter TD. A brief discussion of scleroma (Rhinoscleroma) with a report on some cases seen in Rhodesia. Cent Afr J Med 1966;12:159-61 8. Lubin JR, Jallow SE, Wilson WR, Grove AS, Albert DM. Rhinoscleroma with exophthalmos: a case report. Br J Opthalmol 1981;65:14-7 9- Andraca R, Edson RS, Kern EB. Rhinoscleroma: a growing concern in the United States? Mayo Clinic experience. Mayo Clin Proc 1993;68:1151-7 10. Soni NK. Scleroma of the lower respiratory tract: a brochoscopic study. J laryngol Otol 1994;108:484-5 11. Gaafer HA, el Assi MH. Skin affection in rhinoscleroma: A clinical, histological and electron microscopic study on four patients. Acta Otolaryngol 1988;105:494-9 12. Bahri HC, Bassi NK, Rohatgi MS. Scleroma with intracranial extension. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1972;81:856-9 13. Paul C, Pialoux G, Dupont B, Fleury J, Gonzales-Canali, Eliaszewicz M, et al. 1 Infection due to Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis in two patients infected with human . Clin infect Dis 1993;16:441-2 14- Meyer PR, Shum TK, Becker TS, Taylor CR. Scleroma (Rhinoscleroma). A histologic immunohistochemical study with bacteriologic correlates. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1983;107:377-83 15. Amoils CP, Shindo ML. Larygotracheal manifestations of rhinoscleroma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1996;105:336-40 17. Diallo BK, Diallo M, Kane A, Diop Y, Niang ND, Toure S, et al. A new case of rhinoscleroma with skin extension. Rev Laryng Otol Rhinol 2004;125:253-5 18. Batsakis JG, el-Naggar AK. Rhinoscleroma and rhinosporidiosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1992;101:879-82 19- De Champs C, Vellin JF, Diancourt L, Brisse S, Kemeny JL, Gilain L, et al. Laryngeal scleroma associated with klebsiella pnuomiae subsp. Ozaenae . J Clinl Microbiol 2005;43:5811-3 20. Lyengar P, Laughlin S, Keshavjee S, Chamberlain DW. Rhinoscleroma of the larynx. Histopathology 2005;47:224-5 21. Omeroglu A, Weisenberg E, Baim HM, Rhone DP. Pathologic Quiz Case: Supraglottic granuloma in a young Central American man. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2001;125:157-8 22. Soni NK,. Scleroma of the larynx. J Laryngo Otol 1997;111:438-40 23. Maguina C, Cortez-Escalante J, Osores-Plenge F, Centeno J, Guerra H, Montoya M, et al. Rhinoscleroma: eight Peruvian cases. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2006;48:295-9 24.de Pontual L, Ovetchkine P, Rodrigus D, Grant A, Puel A, Bustamante J, et al. Rhinoscleroma: a French national retrospective study of epidemiological and clinical 1 features. Clin Infet Dis 2008;47:1396-402 25. Fawaz S, Tiba M, Salman M, Othman H. Clinical, radiological and pathological study of 88 cases of typical and complicated scleroma. Clin Respir J 2011;5:112-21 27. Hart CA, Rao SK. Rhinoscleroma. J Med Microbiol 2000;49:395-6 28.Abdel Razek AA. Imaging of scleroma in the head and neck. Br J Radiol 2012,85:1551-5 29. Razek AA, Nada N. Role of MR imaging in laryngoscleroma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2013;270:985-8 1 Summary The observed prevalence of glottic and suproglottic manifestations of Rhinoscleroma was higher than in previous reports. The results point to that advanced laryngeal manifestations of Rhinoscleroma were associated with late nasal stages of the disease. The observed laryngeal manifestations of Rhinoscleroma in our endemic area differ than other reports from non-endemic areas. 1 Tables Legend Table I: Correlation between the nasal and laryngeal findings in the study patients 1