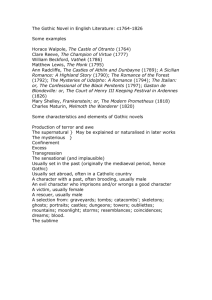

GOTHIC LITERATURE: INTRODUCTION

advertisement

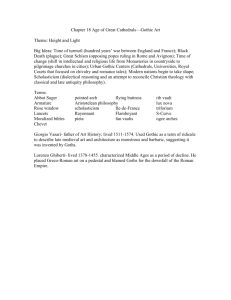

GOTHIC LITERATURE: INTRODUCTION The origins of Gothic literature can be traced to various historical, cultural, and artistic precedents. Figures found in ancient folklore, such as the Demon Lover, the Cannibal Bridegroom, the Devil, and assorted demons, later populated the pages of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Gothic novels and dramas. In addition, many seventeenth- and eighteenth-century works are believed to have served as precursors to the development of the Gothic tradition in Romantic literature. These works include plays by William Shakespeare, such as Hamlet (c. 1600–01), and Macbeth (1606), which feature supernatural elements, demons, and apparitions, and Daniel Defoe's An Essay on the History and Reality of Apparitions (1727), which was written to support religion and discourage superstition by providing evidence of the existence of good spirits, angels, and other divine manifestations, and by ridiculing delusions and naive credulity. However, while these elements were present in literature and folklore prior to the mid-eighteenth when the Gothic movement began, it was the political, social, and theological landscape of eighteenth-century Europe that served as an impetus for this movement. Edmund Burke's treatise A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757) introduced the concept of increasing appreciation for the nature of experiences characterized by the "sublime" and "beautiful" by depicting and then engaging (vicariously) in experiences comprised of elements that are contrary in nature, such as terror, death, and evil. Writers composed Gothic narratives during this period largely in response to anxiety over the change in social and political structure brought about by such events as the French Revolution, the rise in secular-based government, and the rapidly changing nature of the everyday world brought about by scientific advances and industrial development, in addition to an increasing aesthetic demand for realism rather than folklore and fantasy. The Gothic worlds depicted fears about what might happen, what could go wrong, and what could be lost by century, continuing along the path of political, social, and theological change, as well as reflecting the desire to return to the time of fantasy and belief in supernatural intervention that characterized the Middle Ages. In some cases Gothic narratives were also used to depict horrors that existed in the old social and political order—the evils of an unequal, intolerant society. In Gothic narratives writers were able to both express the anxiety generated by this upheaval and, as Burke suggested, increase society's appreciation and desire for change and progress. It is Horace Walpole's novel The Castle of Otranto (1764) that is generally acclaimed as the original work of Gothic literature—despite the fact that some of the Gothic trappings found in Walpole's work were present in works such as Tobias Smollett's The Adventures of Ferdinand Count Fathom (1753)— because in his narrative Walpole brings together elements of the supernatural and horrific, and models his ruined castle setting after his real-life residence, Strawberry Hill, a modern version of a medieval castle. The characters in the novel try to succeed in the modern world and to adhere to the optimism and forwardlooking agenda they have been asked to advance, but a dark, ancient evil from the distant past dooms them to failure. While the literary merits of Walpole's novel were challenged by many critics, the work inspired the reading public and authors alike, and works imitative of Otranto, written in what became known as the Gothic style, became extremely popular. Brother and sister John Aikin and Anna Laetitia (Aikin) Barbauld, in their Miscellaneous Pieces in Prose (1773), represent the intellectual and psychological mechanics of Gothic literature, and offer "Sir Bertrand, A Fragment," a story written in Gothic style, to illustrate their assertions. Ann Radcliffe, like Walpole, is considered one of the founders of the Gothic genre. Radcliffe began her career as a Gothic writer with the publication of her well-received novel The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne in 1789, and quickly followed up with the novels A Sicilian Romance and The Romance of the Forest published in 1790 and 1791, respectively. Radcliffe's 1794 novel, The Mysteries of Udolpho is regarded by many as the quintessential example of eighteenth-century fiction at its finest, and it is for this work that she is best known. Mrs. Eliza Parsons's Castle of Wolfenbach (1793) is an example of the melodramatic popular "shilling shocker," or "penny dreadful" type of Gothic fiction, a debased imitation of Radcliffe's style, characterized by gross excess and lack of literary skill, that was parodied by Jane Austen in Northanger Abbey (1818). Parsons was one of many novelists, including Edward Bulwer-Lytton—held as an author of a more "elevated," or skilled example of the popular Gothic melodrama—who produced works of this kind. Other works considered classic examples of the Gothic novel are Matthew Gregory Lewis's The Monk (1796), and Charles Robert Maturin's Melmoth the Wanderer (1820), both of which epitomize the stock Gothic character of the outsider, or social outcast, who must face the consequences of committing mortal sin. The great Romantic poets Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, John Keats, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge also contributed to the Gothic tradition in literature, and, according to critic Fred Botting, produced "major innovations, or renovations of the genre" that "drew it closer to aspects of Romanticism." The Romantic writers, asserts Botting as well as other commentators, while utilizing the settings and devices developed by Walpole, Radcliffe, and others, focused and expanded upon the psychological, internal qualities of the protagonists, and dealt with such themes as the search for identity, desire versus duty, social alienation, and the search for truth. William Godwin, and his daughter, Mary Shelley, are the Romantic writers most closely associated with the Gothic tradition. Godwin's Things as They Are; or, The Adventures of Caleb Williams (1794) utilizes the Gothic tradition to indict political repression and protest the tyrannical rule of the day, while Shelley's Gothic in Frankenstein (1818) urges personal integrity and social responsibility in an age of scientific progress, and represents the anxiety produced by the disruption of the traditional, known natural world order. While English writers are credited with founding the Gothic novel, Scottish writers such as James Hogg contributed heavily to the genre, and many English-language works were influenced by German literary traditions, particularly the works of such writers as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and E. T. A. Hoffmann. Sir Walter Scott's works reflect a German sensibility, and works such as his Waverly (1814)—as well as the works of others, including Walpole, Radcliffe, Shelley, Maturin, and Lewis—in turn inspired Charles Brockden Brown, Edgar Allan Poe, and James Fenimore Cooper, some of the most notable authors who developed what became the American Gothic tradition in literature. In addition, the English Gothic tradition influenced French authors, including Gaston Leroux, and Russian authors, including Fyodor Dostoevsky and Anton Chekhov. Since its inception, the Gothic genre in literature has undergone numerous changes and adaptations, but its essential role as a means of depicting humanity's deepest, darkest fears and otherwise unspeakable evils—both real and imagined—has endured. Gothic > Intro There are two distinct Gothic styles in the eighteenth century. The first, what we might call “early eighteenth-century Gothic,” is a revival of medieval styles, especially in architecture, as a form of cultural nationalism. Manor houses were built in the style of the Tudor castles of the Middle Ages because this were thought to be an indigenous “English”style that symbolized the English values of tradition, security, and strength at a time of great political and economic rivalry with France. In the later eighteenth century, the Gothic style came to be associated with another aspect of medievalism: the mysterious and spooky world of the Catholic church at the time of the Inquisition, for example, and the bright jewel-like colors, flat perspective, and sometimes gory piety of fifteenth-century church painting. So we might see early eighteenth-century Gothic manor houses using the classic pointed arch of the Gothic style, but the same pointed arch in a late-century building like Walpole’s Strawberry Hill is used in an exaggerated, almost campy way to symbolize style for its own sake, even decadence. The later Gothic style also expanded to include Gothic literature, paintin