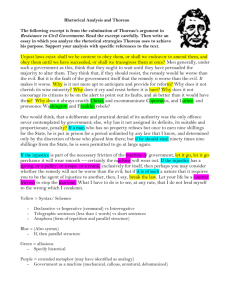

Models that link Teaching for Social Justice

advertisement

TSJ Models Edu 430/530 Professionalism and Social Justice TSJ Models Models that link Teaching for Social Justice to pedagogical practice and curriculum development. Developed by Pat Russo and Anne Fairbrother In the SUNY Oswego School of Education, we define Teaching for Social Justice as both a principle and a goal. Adams, Bell, & Griffin (1997) provide a more in depth discussion of the nature of this goal to guide our work: We believe that social justice education is both a process and a goal. The goal of social justice education is full and equal participation of all groups in a society that is mutually shaped to meet their needs. Social justice includes a vision of society in which the distribution of resources is equitable and all members are physically and psychologically safe and secure. We envision a society in which individuals are both self-determining (able to develop their full capacities) and interdependent (capable of interacting democratically with others). Social justice involves social actors who have a sense of their own agency as well as a sense of social responsibility toward and with others and the society as a whole. (p. 3) We recognize that Teaching for Social Justice is an essential component of our programs to prepare candidates to help all students learn, grow, and flourish. Our goal is that candidates will become advocates for all children, proactively resisting/addressing injustice within and beyond the classroom. Pedagogical Practice The best statements and examples of Teaching for Social Justice are provided in a number of books published by the Rethinking Schools organization (www.rethinkingschools.org). In one volume, the editors (Bigelow et al, 1994) define Teaching for Social Justice in the following way: …a common social and pedagogical vision unites this collection. This vision is characterized by several interlocking components that together comprise what we call a social justice classroom…we argue that curriculum and classroom practice must be: Grounded in the lives of our students Critical Multicultural, anti-racist, pro-justice Participatory, experiential Hopeful, joyful, kind, visionary Activist Academically rigorous Culturally sensitive (pp. 4-5) In the next section, we share information about seven models that exemplify Teaching for Social Justice practice that we have compiled as a result of reviewing a number of resources. For each model we provide a brief description, some lesson descriptions, and several resources. We realize that this source book is to be used by student teachers who are placed in grades 1-12. Because of this, we have tried to provide samples of lesson descriptions that cross all grade levels and all content TSJ Models areas. However, we expect student teachers to use the best of their creativity to extrapolate ideas from these examples that are would work for their unique classroom setting. Teaching for Social Justice Model 1. Difference-Injustice-Justice: This model, derived from Derman-Sparks & the A.B.C. Task Force (1989), has three key components: Recognize and value difference; identify and name injustice; talk about and plan to address injustice Although the anti-bias curriculum plans were developed for use with early childhood programs, their strategies can be used at any level pre-K through 12 (and beyond). This model is one of the most basic frameworks for thinking about TSJ. In nearly all models, there is some attention to helping students recognize and value differences of race/ethnicity, gender, (dis)ability, class, sexuality, family structure, religion, and/or language. Also, all the models draw attention to helping students identify and name examples of injustice that occur around difference. Nearly always, when we help students to identify injustice, they want to do something about the injustice they now see. Thus, the third part of this basic approach is to help students talk about and/or plan to address the injustice they have uncovered. How does this play out in the classroom? Because this model is such a basic framework, the model shows up in many different classrooms, in many different ways. You will see this in the range of examples we provide in the following section. Begin at this point: Imagine lessons in which you address all three of these things: differenceinjusticejustice Avoid the myth that by talking about difference (or injustice) that the talk will only encourage poor attitudes. Instead think about helping kids to develop language for the things they see around them. Avoid your tendency to stop conversation by telling the kids about how alike we all are. We are alike in many ways, but injustice tends to grow from how we perceive differences, so focus on the injustice, rather than avoiding it. When students embrace a climate of valuing difference, of seeing how difference strengthens and deepens what a group can do, then injustice will diminish. Avoid thinking that the only difference to be discussed is the difference within your classroom. Do not single out the one Latino boy, or the one girl with two moms, or the one kid with a physical disability. Instead talk about difference between the people that show up in your curriculum. Find literature that addresses differences, and use that to start conversations. Use word problems in math lessons that address injustice. Talk about injustice around issues in social studies lessons. Find issues relating to social justice as you teach science concepts. The following lesson descriptions provide some examples of this model. Derman Sparks and the ABC Task Force (1989). Chapter 8, “Learning To Resist Stereotyping and Discriminatory Behavior.” Pp. 69-76. Sleeter & Grant (2007). Turning On Learning. Folk and Fairy Tales Lesson Pp. 206-209. TSJ Models Rethinking Our Classrooms, Volume 1, “Tapping Into Feelings of Fairness” pp. 44-48 Teaching for Social Justice Model 2. Critical Lens: Develop a critical lens for viewing the world (Banks & McGee Banks, 1997) that includes recognizing patterns of privilege and/or disadvantage; identifying and unpacking stereotypes; and noticing how social attitudes result in the valuing or devaluing of people from particular social groups. Teaching for social justice is teaching that arouses students, engages them in a quest to identify obstacles to their full humanity, to their freedom, and then to drive, to move against those obstacles. And so the fundamental message of the teacher for social justice is: You can change the world. (Ayers, 1998, p. xvii) When we use the term “critical lens” here, we are not talking about what is often referred to as “critical thinking” in schools. In “critical thinking” we usually focus on increasing students’ reading comprehension by helping them understand cause/effect relationships, or sequencing of events, or maybe even character development. When we use the term “critical lens” in terms of teaching for social justice we are talking about helping students see the world with an eye that is sensitized to noticing injustice in its many forms. Once you begin noticing injustice in the world, you tend to see it all around you: on television, at the movies, in store displays, in interactions between people at the mall, in the workplace, and even in your own family. By helping students attend to evidence of injustice around issues of race, class, gender, sexuality, (dis)ability, religion, or language, you will sharpen the lens they use to view their world. However, if you try to simply tell students that this or that example is evidence of injustice, they will likely reject your suggestions. Instead, to help students develop a critical lens, you should work to present them with information (or help them to collect information) that they can use to draw their own conclusions about social injustice. Then you can help them learn skills for analyzing what they are seeing, and for addressing the issues of injustice they raise. The following lesson descriptions provide some examples of this model. Sleeter & Grant, Turning On Learning: Stereotypes Lesson, pp. 106-109 Reading, Writing and Rising Up, “Unlearning the Myths That Bind Us: Critiquing Cartoons and Society,” pp. 40-47 and 50-51. Rethinking Mathematics, “Ten Chairs of Inequality,” pp. 135-137 Rethinking Our Classroms Vol 2, “Teaching Math Across the Curriculum,” pp. 84-88 TSJ Models Teaching for Social Justice Model 3. Simulations of Exclusion: Develop an understanding of the impact of exclusionary practices through simulations; and then move beyond feelings of empathy (or sympathy) toward an analysis of injustice. Caution: This model should only be used with careful thought about your students’ strengths and needs, and with careful planning. This model begins with a classroom simulation that is designed so that some of the students are purposely left out of some classroom activity, denied classroom privileges, or denied the use of their sight, hearing, hands, or mobility. During the simulation, the teacher often makes the situation more frustrating by doing or saying things that further handicaps the excluded students. After 10 minutes, or an hour, or sometimes more than an hour, the simulation stops and the class discusses the experience, usually with the students who were excluded talking about how it felt to be left out. The best known example of this kind of exercise was developed by then teacher, Jane Elliott, following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968. This lesson is known as the “Blue Eyes, Brown Eyes Experiment” (see www.janeelliott.org). However, to use this model from a teaching for social justice stance, the teacher needs to take the discussion further than simply talking about how it feels to be left out. Following the simulation, it is important to discuss the event and the feelings that this simulation elicited. The teacher should be sure to examine feelings of being left out, but also the feelings (and thoughts) of the students who were included, privileged, or allowed to be able-bodied. This is a key point of departure into discussions of injustice. For another discussion of this topic see the document “Teaching About People With Disabilities and Social Justice,” in the Hot Button Issues section later in this packet. These are some things we know about exclusion in our society today: there are always people who are included or excluded (because of issues of race, class, gender, sexuality, (dis)ability, religion, language, and other characteristics) people who are privileged (included) often do not realize that exclusion is going on for others when people who are excluded complain, others often do not understand the basis of their claim sometimes people who are excluded do not even realize it is happening to them sometimes people think their privileges are deserved and only a result of their hard work (even though this isn’t always the case) sometimes people assume others deserve to be left (excluded) out because of their lack of effort (they fail to see the structure that routinely excludes people automatically)—in teaching for social justice terms we call this: discrimination or oppression injustice exists as a result of the confusing assumptions and attitudes about exclusion and inclusion TSJ Models in order to understand and challenge such injustice, we try to help students identify situations where people have been left out (excluded) even though they deserve to be included Later in this packet, in the section titled “What Does It Mean to Teach For Social Justice,” there are many examples of inclusion (privilege) and exclusion (discrimination or oppression) provided in the sections on race, class, gender, sexuality, and (dis)ability. When teachers use this model in their classroom lessons, after talking about feelings of being left out, it is important to move the discussion to issues of fairness when inclusion or exclusion occurs. Note: A simulation is not the same as a role playing exercise. In a simulation students do not pretend to be someone else, or pretend to know what someone else is thinking. In a simulation, the students act like themselves within an artificial situation that the teacher sets up. Caution: Because this model calls for a simulation where some students are actually left out, and expected to feel bad, if this activity isn’t done carefully the students may become needlessly upset. There are many strategies you can use to help prepare the students for the activity, or to prepare an activity that minimizes this risk. Also, these types of activities should never be used before a very comfortable, trusting, and caring relationship has been developed between the teacher and the students. The following lesson descriptions provide some examples of this model. Rethinking Our Classrooms, Vol 2 “A Lesson On the Japanese-American Internment,” pp. 73-74 Rethinking Our Classrooms, Vol 1, “The Organic Goodie Simulation,” ppl 88-90 Wink, J (1997). section of Chapter 5, pp. 101-103. in Critical Pedagogy: Notes From the Real World. Boston: Pearson (Allyn and Bacon). TSJ Models Teaching for Social Justice Model 4. Critical Studies of Cultural Groups: Teach about cultural groups (within the US or beyond) in a way that includes multiple perspectives, issues of power and privilege, dominance or subordination, privilege or exclusion, advantage or disadvantage. Here the term critical refers to considering issues of oppression or injustice within the lessons. Use the wonderful features of the World Wide Web to explore a fuller picture of any cultural group (historic or current). Your approach should be sure to: Include multiple perspectives of events or circumstances Use primary documents that represent the authentic voice of the cultural group Provide information about discrimination, oppression, or exploitation of the cultural group Make links between historical and current experiences of a cultural group Share more comprehensive (and truthful) information about holidays, heroes’ experiences Situate the experiences and struggles of one cultural group within the larger story of struggles for social justice, independence, and/or human rights Notice: This approach lends itself quite well to the use of Documents Based Questioning (DBQ) activities that are currently used in the K-12 curriculum. Avoid teaching about the following: "heroes and holidays" (Banks, 1999; Lee et al, 1998), where you only present one perspective, or a misrepresentation of particular heros or holidays (see hot button issue document later in this packet) "tourist curriculum" (Derman-Sparks, 1989), where you view a society as if you were tourist, only looking for entertaining experiences "exotic" examples of cultures, where you only focus on traditional, or mythic, or idealized stories of a particular cultural group’s history or current existence The following lesson descriptions provide some examples of this model. Rethinking Columbus, “Discovering Columbus: Re-reading the Past,” pp. 17-22 Turning on Learning, Lesson Plan: Back Home During World War II (Before) to Japanese Americans—U. S. Citizens (After) and Why the Changes. Pp. 154-156 Rethinking Our Classrooms, Volume 2, “Unsung Hereos” pp. 34-36. Rethinking Our Classrooms, Volume 2, “Teaching About Unsung Heroes,” pp. 37-41 Rethinking Our Classrooms, Volume 2, “Discovering the Truth About Helen Keller,” pp. 42-44. Rethinking Our Classrooms, Volume 1, “The Politics of Children’s Literature: What’s Wrong With the Rosa Parks Myth?” pp. 137-140. Turning On Learning. Mong History, pp. 44-49. TSJ Models Teaching for Social Justice Model 5. Critical Culturally Relevant Teaching. Use culturally responsive (Gay, 2000), culturally relevant (Ladson-Billings, 1994), and student centered pedagogical practices. This model and the next model (Authentic Learning) both call on teachers to include the lived experiences of their students within the lessons. In this model, we focus on understanding the general cultural experiences and backgrounds of the students in the teacher’s classroom. In the next model, we will focus on teachers attending to the unique (according to time and place) day to day experiences students bring into the classroom. Darling-Hammond and others (2002) remind us of the important link between students and their social cultural experiences: A critical task in becoming an effective teacher of diverse students is coming to understand individual young people in nonstereotypical ways while acknowledging and comprehending the ways in which culture and context influence their lives and learning. (p. 209) Banks and McGee Banks (1995) refer to this model as "equity pedagogy:" We define equity pedagogy as teaching strategies and classroom environments that help students from diverse racial, ethnic, cultural groups attain the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to function effectively within, and help create and perpetuate, a just, humane, and democratic society. (p. 152) Teachers who successfully implement equity pedagogy draw upon a sophisticated knowledge base. They can enlist a broad range of pedagogical skills and have a keen understanding of their cultural experiences, values, and attitudes toward people who are culturally, racially, and ethnically different from themselves. (p. 156) Most recently, Darling-Hammond and Bransford (2005) state the importance of this model for supporting student learning: When teachers develop a "socio-cultural consciousness," they understand that individuals' worldviews are not universal but are greatly influenced by their life experiences, gender, race, ethnicity, and social-class background (Banks, 1998; Villegas and Lucas, 2002a). This kind of awareness helps them to better understand how their interactions with their students are influenced by their social and cultural location and helps them develop attitudes and expectations—as well as knowledge of how to incorporate the cultures and experiences of their students into their teaching—that support learning. In addition to constructing culturally responsive curriculum and teaching, teachers need to be prepared for learning differences and disabilities that are prevalent in the inclusive classroom. (p. 36) We understand culturally relevant teaching to mean doing the following in your curriculum and your pedagogical practice: Using the lived experiences of your students as members of distinct cultural groups (make connections to students’ home lives and families, especially in terms of traditions, values, ways of communicating) Acknowledging the cultural distinctions among your students (and valuing them) Recognizing the historical and current characteristics of cultural groups that your students represent (helping your students learn about this) Understanding that your students have different material wealth, and accommodating instruction, assignments (especially homework), and classroom activities to account for this Accepting, valuing, and understanding different language patterns of your students (while you teach curriculum to help your students achieve academically) TSJ Models These strategies are necessary for Teaching for Social Justice, but they are not sufficient for a teacher who wants to teach for social justice. In order to in TSJ in this approach, teachers must also attend to the following: Situate the experiences of your students within the larger school community, local community, state, region, national community, and global community Make use of the strategies in TSJ Model 1 (above), DifferencesInjusticeJustice (address issues of injustice within this approach) Remember, in most middle class, European American, able-bodied classrooms, we have traditionally taught in a culturally relevant way. The curriculum materials, the classroom activities and discussions, and the teacher’s language patterns all reflected European American, middle class experiences. Even if all (or most) of your students reflect this description, you can teach in a culturally relevant way by helping your students understand how their experiences are situated within the current (and historical) context of US culture. Keep in mind: Only 75% of Americans are European American Only 60% of Americans are middle class (or richer) Only 85% of Americans are able-bodied Only 50% of Americans are men Only 80% of Americans are heterosexual Also keep in mind that when we talk about cultural differences, there are usually examples of discrimination or oppression around issues of: Race (and/or ethnicity) gender class status sexuality (and/or family structure) (dis)ability language religion Culturally relevant teaching that occurs within a TSJ framework includes attention to cultural differences as well as the injustice that occurs around difference. The following lesson descriptions provide some examples of this model. Turning On Learning, Lesson, Word Usage (Before, After, and Why the Changes), pp. 41-44. Turning On Learning, Lesson, Story Writing (Before), Story Quilt (After), Why the Changes, pp. 133-136 Rethinking Our Classrooms, Vol 1, “Teaching for Social Justice: One Teacher’s Journey” pp. 30-33 Reading, Writing, and Rising Up, “Reading, Writing, and Righteous Anger: Teaching About Language and Society. Pp. 105-114. TSJ Models Teaching for Social Justice Model 6. Authentic learning. Critically ground abstract, historical, or literary content in the real-world, present day experiences and/or interests of the students (Bigelow et al, 1994). Adams and others (1997) claim, "Our approach to social justice education begins with people's lived experience and works to foster a critical perspective and action directed toward social change." (p. 14) This model and the previous model (Culturally Relevant Teaching) both call on teachers to include the lived experiences of their students within the lessons. In this model, we focus on the specific day-to-day experiences, or the unique interests of the students in the teacher’s classroom. This approach can be depicted through the following story. Fifth grade classroom, small town school, the students file into the classroom after lunch, talking, laughing, getting out materials for the next activity. Suddenly one student notices something happening outside. He alerts the others who quickly line up against the windows to see a man across the field shouting at and hitting his little dog. The man throws the dog down and attempts to kick it, and then throws stones at the cowering dog. The children are quite upset at what they are witnessing. Questions rise from the din: What’s he doing? Shouldn’t we stop him? Shouldn’t we call someone? The teacher arrives to the window and in an attempt to calm down the atmosphere begins to close the blinds, and tell the kids to take their seats, assuring them that someone will take care of this. The kids reluctantly take their seats and the classroom goes on with business as usual. This story is an example of a teacher who avoids using authentic learning and/or TSJ. This teacher has avoided linking the experiences the students to the curriculum. The teacher also avoided an opportunity to help the students address an issue that they obviously saw as an injustice. We understand authentic learning in a TSJ context to mean doing the following in your curriculum and your pedagogical practice: Link the current lived experiences and/or individual interests of your students to your curriculum Acknowledge the distinctions among your students (and value them) Situate the experiences (and/or interests) of your students within the larger school community, local community, state, region, national community, and global community Make use of the strategies in TSJ Model 1 (above), DifferencesInjusticeJustice (address issues of injustice within this approach) The following lesson descriptions provide some examples of this model. Reading, Writing, and Rising Up. “Where I’m From: Inviting Students’ Lives Into the Classroom.” Pp. 18-22. Rethinking Our Classrooms, Vol 1, “My Mom’s Job is Important,” pp. 70-71 Rethinking Our Classrooms, Vol 1, “ Math and Media: Bias Busters,” p. 84 Rethinking Mathematics, “Deconstructing Barbie,” pp. 122-123 (** try doing the same with GI Joe). Turning On Learning, Lesson, City Government, Before, After and Why the Changes, pp. 293-296. Turning on Learning, Lesson, Toys (Before, After, and Why the Changes), pp. 80-83 TSJ Models Teaching for Social Justice Model 7. Anti-Oppression Work. Directly address issues of racism, sexism, classism, heterosexism, able-ism, and other structures of oppression. The book Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice: A Sourcebook (Adams, Bell, Griffin, 1997) has been our best guide for understanding this Teaching for Social Justice model. Its Editors state: Social justice education includes both an interdisciplinary subject matter that analyzes multiple forms of oppression (such as racism and sexism), and a set of interactive, experiential pedagogical principles that help students understand the meaning of social difference and oppression in their personal lives and the social system. (p. xv) We use the term 'oppression' rather than discrimination, bias, prejudice, or bigotry to emphasize the pervasive nature of social inequality woven throughout social institutions as well as imbedded within individual consciousness. Oppression fuses institutional and systemic discrimination, personal bias, bigotry, and social prejudice in a complex web of relationships and structures that saturate most aspects of life in our society. (p. 4) This model reflects efforts of teachers who infuse a vision of working for social justice across several lessons and/or units (and/or weeks or months) of the year’s curriculum. In this approach, teachers might begin the year (or month, etc) talking about the human struggle for justice, or the on-going development of just and democratic communities, or the trail of everyday heroes throughout a community’s history, or any other of a number of themes that would allow for discussions of injustice to be included within the school year. Teach about struggles for justice, democracy, freedom, civil rights, and/or activism (or others) across several groups or issues. For example: anti-racism work that compares the efforts of African-Americans, Latinos, Chicanos, Asians, Native Americans, Puerto Ricans etc); civil rights struggles that compares the efforts of Blacks, People with Disabilities, Women, Gays and Lesbians, Poor People immigration issues that compares northern Europeans, southern Europeans, Latin Americans, Asians resistance to oppression that compares struggles of exploited or colonized countries; sweatshop workers, unionized employees, Native Americans, US slaves and other subjugated groups (Mexicans, Chinese, Japanese, women) the tensions between a process of assimilation (and/or normalization) and a process of maintenance of cultural identity that are reflected in our history, economy, politics, literature, music, art, math, science, and technology, and/or popular culture The following lesson descriptions provide some examples of this model: Turning On Learning: Lesson, African American Literature, Before, After, and Why the Changes: pp. 320-324 Turning On Learning: Lesson, Rate and Line Graph (Before, After, and Why the Changes), p. 289-293. Turning On Learning: American Indians in Our State (Before), American Indians and Institutional Racism (After), and Why the Changes. Pp. pp. 140-145 Rethinking Our Classrooms, Vol 1, “Taking the Offensive Against Toys,” p. 96 Reading, Writing, and Rising Up, “What Happened to the Golden Door?: How My Students Taught Me About Immigration,” pp. 144-155.