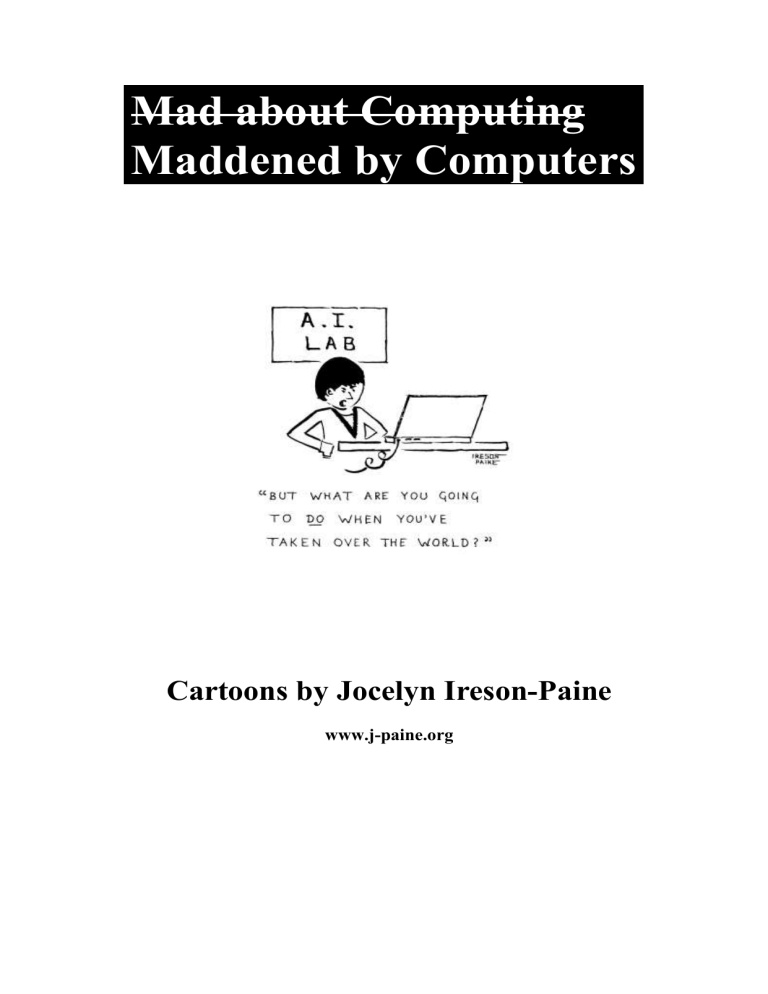

AI Phone Home: - Jocelyn Ireson

Mad about Computing

Maddened by Computers

Cartoons by Jocelyn Ireson-Paine

www.j-paine.org

About these Cartoons

Since March 2008, I've been blogging for Dobbs Code Talk . This is the online incarnation of a journal that began in 1975 during the hobby-computer era, originally giving itself the splendid title of Dr. Dobb's Journal of Tiny BASIC Calisthenics & Orthodontia : Running

Light without Overbyte . Some of my postings are cartoons, and these are they. This is an updated version of the booklet I displayed at Caption 2009, and has more cartoons and fewer essays. The Caption 2009 one is at www.j-paine.org/dobbs/pentel_brush_pen.html .

My bloggings, written as well as drawn, are indexed from my own site at www.jpaine.org/dobbs/ .The cartoons, plus a few sketches, are also in a separate blog at www.jpaine.org/blog/jocelyns_cartoons/ .

I drew most of the cartoons, and most of each cartoon, with a Pentel Brush Pen. Thanks to

Oxford’s Brush & Compass, now merged with Broad Canvas, for introducing me to this splendid instrument, and maintaining a regular supply of cartridges as well as replacement pens.

Jocelyn Ireson-Paine www.j-paine.org popx@j-paine.org

With thanks to Ranjix, Sebastian Straube, and the Oxford Print Centre in Holywell Street.

2

Happy New Year

30th December 2008

The text in the thought bubble is something that many programmers will recognise as diagnostics from a Java program that has crashed. A crash that could take longer than a day to fix...

3

Scenes from a New Depression: Number Twenty-

Seven

3rd January 2009

4

Reprogramming Aibo

Aibo was Sony’s robot dog, which they stopped making in 2006. Although Sony intended it as a toy, many universities used it for teaching computer-science students how to program robots.

5

Intractability

12th January 2009

To a computer scientist, difficulty is about space and time. How fast the memory needed by a program increases as the problem it’s solving grows, or how fast the running time increases.

And although some problems have relatively modest needs, the so-called Travelling Salesman problem is known to all as being supremely hard. The real world has other measures of difficulty.

6

Filtering the Inauguration

I wanted to entitle this Spam in a Klan , but decided it would give too much away. On the day

Obama's victory was announced, one of my customers phoned urgently about problems with his Web site. One of these turned out to be a spamspike.

We do get spamspikes, his hosting company's owner told me. Sometimes, spam shoots to ten times its normal level. As it had in this spike — anti-Obama hate-mail and death-threats, courtesy of the American Far Right. Perhaps my drawing is unfair, symbolising them as I did.

If so, I apologise to the Ku Klux Klan.

But not, I feel, to all of it. Read down to the end of the Imperial Klans of America

International Headquarters page at www.kkkk.net . It is scary. Even the animation at the top is scary.

I can never remember whether to say "Klux" or "Kux". But now it's easy to remember, because I once learned Greek, and Wikipedia tells me the name is from κύκλος, Greek for

"circle". Also, I have never been inside an Internet hosting company. Some details in my drawing may therefore be wrong.

20th January 2009

7

Bound to be Called

In the most respected programming languages, functions — such as the act of squaring a number, or of taking its cosine — are what computer scientists term “first class values”. They can be stored in variables, and calculated with by passing them into and out of other functions. Such languages thereby become hugely versatile.

“Object-oriented languages” such as Java, on the other hand, put functions in bondage. They name them “methods” and tie them to objects, making it impossible to use them freely. This has never seemed sensible to me — function is, after all, only the most important concept in the whole of mathematics. It didn’t seem sensible to Dobbs blogger Bill Lewis either, who posted a piece about it titled How much would you pay for a closure?

(“Closures” are a trick in computing that helps a language make functions into first class values.) So I drew this.

8

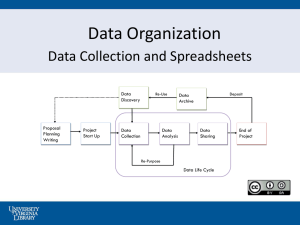

Fatal Addition

I've pinched my title from a New Scientist feature which reported on research into spreadsheet errors. Professor Ray Panko at the University of Hawai'i had examined ten years of spreadsheet-error studies and found every one to show a dangerously high rate of errors. He estimated that humans make around one error per hundred spreadsheet cells.

Accountants Coopers and Lybrand found errors in 90% of the spreadsheets they looked at.

And the Computer Audit Unit of HM Customs and Excise also found errors. In only 11% of spreadsheets — but some errors ran to millions of pounds.

The fault, of course, is with the human brain, never evolved for worlds where small errors can lie unnoticed for years, then return and bite you a millionfold. We can do nothing about that.

But we can make more helpful software.

9

Did Spreadsheets Crash the City?

I research into ways of building spreadsheets more safely, which is why I have spreadsheet cartoons. A good way to make any system easier to build is to stock prefabricated components, tested and documented. Even should these be not free, the money spent buying them is probably less than the wages saved — if you doubt this, try building a radio from transistors you fabricated yourself. And, once you have finished a complicated system, you help others by breaking it into components they can reuse.

Computing calls program components “modules”, and speaks of “modular programming”.

Sadly, the world’s most popular spreadsheet, Excel, lacks modules. If you write an Excel spreadsheet and want to give your code to someone else writing an Excel spreadsheet, you must copy and paste cells into their spreadsheet. Not possible if the shapes and positions don’t match, and always at risk from errors. So I was pleased when I developed software to solve the problem; and I drew these cartoons for the European Spreadsheet Risks Interest Group conference where I showed off the software.

The conference opened on July 7 th 2005 in Greenwich, opposite Canary Wharf. Around eleven on that dreadful morning, we learnt of the bombings. The more terrifying because rumour flew. We heard London was “in lock-down”, no-one allowed in or out. The conference chairman asked me whether I thought it tactless to show my first cartoon. Myself,

I don’t see the tactlessness.

10

Spreadsheets Need Modules

The cartoon above was “before modularity”; this one is “after modularity”. Sarbanes-Oxley, by the way, is a piece of US law enacted in 2002 in response to Enron and other accounting scandals. It penalises companies more highly for accounting errors, and sets more stringent standards. So it became even more important to know that one’s spreadsheets were correct.

11

An Ounce of Image

I drew this cartoon on a let’s-have-coffee note to catch my friend Julian Clarke’s eye during another spreadsheet conference: It was inspired by a paper about teaching Excel to novices, by Étienne Vandeput of the University of Liège. Étienne had written that teachers will often teach students how to change fonts and widen columns before they explain how to write formulae. Even more so, before they explain which formulae to write for which kinds of problem.

For these teachers, graphical-interface stuff is more important than correct maths. In the words of the proverb:

An ounce of image is worth a pound of presentation.

I can see why the French live longer than the English. At 9pm on the Monday, I was standing near Cathédrale Notre Dame in bright sunshine, admiring the flying buttresses and the views up and down the Seine. Plenty of time to meander back to the RER station, get back to the conference accommodation just outside Paris, and buy food from a local shop before dusk fell. At 9pm on the Tuesday, having emerged into London in the centre of a titanic hour-long thunderstorm, the first time I'd ever consciously noticed that lightning is blue, I was standing under a sky-sized raincloud, shivering. It felt ten degrees cooler. Dusk was reflected in the puddles on the pavement. This is why the French have joie de vivre whereas the English have tea and custard creams. Especially superb was the joie de vivre provided in liquid form (red, rosé, and white) at our conference lunches.

20th July 2009

12

Proverbs in Pictures I: Don't Count Your Chickens

Before They're Hatched

Language Gap

13

Secrets

This was inspired by a recent customer’s non-disclosure agreement. In case you don’t know the phrase, this is a short legal document which requires me not to divulge the customer’s trade secrets, such as how their programs work.

14

Getting Tough

The people who design programming languages constantly release improved versions.

Sometimes, the improvements add a new feature. If this is safer, more efficient, or otherwise better than an older feature, the designer may call the latter “deprecated”, and make the system warn you if you use it.

15

I Tweet, You're a Twit, He's a Tw*t

Twitter made David Cameron more notorious last week than if nabbed claiming an entire islandful of duck islands on expenses. Interviewed on breakfast radio, he uttered a word that despite denoting a piece of anatomy owned by half the human race, has been deemed so obscene that I believe it was once banned from radio:

The trouble with Twitter, the instantness of it — too many twits might make a twat.

Twitter has been on my mind since I read Spectator journalist Rod Liddle's feature It is the narcissistic middle-aged, not the young, who love Facebook and Twitter . Liddle says few teenagers use Twitter, because they realise how pointless it is to tweet personal confessions such as “I have just tied up my shoelaces. I did the right one first. And then the left.” It’s older people like Stephen Fry, Liddle says, who Twitter obsesses.

I don’t want to read Stephen Fry tweeting about the steak he ate for dinner. I also don't want my messages limited to 140 characters. Perhaps Twitter don't own enough storage to hold longer messages. Then they should hand over to Google. Google have so much capacity that they could issue every single electron with its own URL, and still have space in reserve to tag the extra electrons generated by pair production while the Universe is running. And the positrons.

But in truth, this restriction, and Twitter itself, are as futile as forcing Fermat to write all his maths in margins.

3rd August 2009

16

Primed

17

And no Play

18

The Curse of the Thinking Classes

19

Mis-Guided

20

Labels

If you had a chocolate-cake recipe that told you how to grease the cake tin, then made you go to page 137 to read about mixing the ingredients, and then jumped to page 46 when explaining how to cook them, it would not be easy to follow. Programs that leap between labels like a flea on a dog full of coffee aren't easy to follow either, which is why Earthling computer scientists dislike them. But we might not mind, if we had more fingers.

21

AI Phone Home

Mr. Excel

22

No Earthly Power

23

Bottles

24

Sweet Words

25

Good Weather for Ducks

26

Charity

27

Alien Imperative

28

A4 Billion

29

How to Survive as a High-Energy Physics Sysadmin

I drew this as a birthday card for a friend who is sysadmin — the person who looks after the main computers and answers questions about such things as the Internet and users' file storage

— in a high-energy physics institution. He says the most common, and most annoying, question posed by his users, who are good scientists too single-minded about their research to think much about the computers, is "Where are my files?"

30

Wild Flowers

31

A Plea to the Future

This is a plea to the future.

At the start of every October, in 0th Week and the Oxford University Examination Schools, old students tie, glue, Blu-Tack and pin: insecurely adhesing bamboo canes, A1 card, and society posters to Exam School desks for the enticement of new students. One clambers onto a desk and picks frantically at the end of a reel of Sellotape; another scoots past with 500 termcards fresh from the photocopying shop across the road. Everybody disputes the ownership of scissors.

The Oxford Union; Cherwell; Experimental Theatre; CompSoc, whose display seems to be obsessed with little plastic penguins; the Wine Appreciation Society and the Banana

Appreciation Society. Who, one year, some wag of an organiser placed next to each other.

The Banana Appreciation Society had a 6 foot plastic yellow banana rearing from its desk.

The Wine Appreciation Society did not have a huge plastic grape.

On one desk, a signed photo of William Hague; on another, a portrait of Marx. But on ours, a hardback Emperor's New Mind in its striking blue cover; the opening pages of John Varley's

Overdrawn at the Memory Bank and Vernor Vinge's True Names ; a DVD of The Matrix . A photocopied conversation with Eliza; a proof in Prolog that if John drinks wine, then Mary loves John; an essay, inspired by Searle's Chinese Room and Douglas Hofstadter's A conversation with Einstein's Brain , on what it feels like to be America. A poster announcing that Why Robots Will Feel Emotion would be the next talk given to the AI Society.

I was AI Society President.

As well as promoting AI, I taught AI. I gave lectures, tutorials, and practicals to Oxford psychologists. But that stopped, because the people who chose the degree courses decided AI was irrelevant to psychology. There was no tradition of AI; and Oxford can be very traditional. In 1994, I spotted a Computing Service poster for a new course on using the Web.

"Shall you teach us to write Web pages?" I asked. "No," answered the tutor. "Only to read them. You won't need to write them." Thinking of an acquaintance who was doing a DPhil on the nature of personal identity after resurrection to Heaven — a lovely person and a dedicated scholar, but a futile topic, for if God exists, we shall discover the answer empirically, and if

He doesn't, the effort would be better spent on cancer research — I felt my subject would be better accepted were I teaching theology.

But one day, AI will be theology. Listen to Frederic Brown:

Dwar Ev ceremoniously soldered the final connection with gold. The connection that would link all the computing machines of all the ninety-six billion populated planets into one universe-wide supercomputer.

"I shall ask it a question," said Dwar Reyn, "which no single computer has been able to answer. Is there a God?"

"Yes," thundered the machine's mighty voice. " Now there is a God." Lightning flashed from the sky and fused the switch shut.

That's my condensation of Brown's short-short story Answer . But perhaps we need not wait until we colonise ninety-six billion planets. Here is a famous passage that statistician and

32

cryptographer I. J. Good wrote in his 1965 paper Speculations concerning the first ultraintelligent machine :

Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an "intelligence explosion," and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make.

This is the notion that Vernor Vinge has amplified into his concept of the Singularity: a point in the future when, as progress grows exponentially, the intelligent machines take over their design and the rest of technology, achieving in minutes and nanoseconds what might once have taken years or centuries. And I do hope that this happens. Because, you see, I missed the

Mallard Hunt.

One night in January 1901, Cosmo Lang, later Archbishop of Canterbury, was carried around

All Souls College in a sedan chair. The chair was borne by four of the College dons: two would become the Chief Justice of India and the Minister of Labour, one was the First Church

Estates Commissioner. In front of him, another Fellow bore a dead mallard on a pole. Lang, and the rest of the procession, continued for two hours, parading around the roofs and quadrangles of the college, while singing "Hee was a swapping, swapping mallard". Lang wrote later that he was: preceded by the seniors and followed by the juniors, all of them carrying staves and torches, a scene unimaginable in any place in the world except Oxford, or there in any society except All Souls.

Thus, the All Souls Mallard Hunt. It began, apparently, when a mallard flew out of a drain during the building of All Souls in the 1480s. The dons may have been annoyed that they missed the chance to kill and eat that duck; but for whatever reason, the custom began. A hundred of the most intelligent people in Britain, chasing a duck on a stick. But not often, for the ceremony happens once a century.

In 1801, they killed the mallard, tethering its corpse to the pole and adding its blood to their wine. In 1901 such behaviour was deemed unseemly, so Lang used a stuffed duck. And in

2001, because Animal Rights had made it inapt to use a real duck in any state, they used a wooden one. But other things had stopped being inapt; and so they restored one verse of the

Mallard Song, the one that ran "His swapping tool of generation, Oute swapped all ye wingged Nation."

In 2101, Animal Rights will have become irrelevant. The dons will engineer their own mallard, specifying its brain so that — as they will prove with full formal rigour — although it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it doesn't feel pain like a duck, because it has been designed to be not conscious. Children of five will get Build A Duck Kits in their

Christmas stockings. They'll invoke real live Donald Ducks and Daffy Ducks with Potterish snaps of their fingers, as carelessly as we invoke Java constructors. Talking ducks with soapresistant feather oil and rose-scented poo, to persuade little Bobby that bathtime is good. The

High Table chef at Merton will fire up his Free Wetware Foundation tissue sprayer and evodevo compiler, to design "duck déjà à l'orange": no need for all that fiddly sauce making.

Chocolate duck breast, with cocoa butter in its fat cells. Bald ducks the size of cherry tomatoes, to be fried and eaten whole like whiting in batter, as the dons chat amongst the

Victorian oak and James II silverware.

33

But — and this is the absolutely salient point — I missed the Mallard Hunt. And it happens only once a century. And I might fall under the proverbial bus before the next one. And I do so want to watch the Mallard Hunt collide with the Singularity.

For that matter, what will happen to the rest of Oxford? As the college with the earliest statutes, Merton has survived the Black Death, the Hundred Years War, the Peasants' Revolt, the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the Civil War, the South Sea Bubble, two World Wars, and Maggie Thatcher. Did you know that once a year, on the day the clocks go back, Merton students take part in a Time Ceremony, parading backwards around the Fellows' Quadrangle while drinking port for the hour between 1am and 1am? They hope, by setting up this continuous rotation, to emit "chronicules", and thereby equalise the flow of time between the college and the rest of the world. Will Merton still be there in 3000 AD? What strange ceremonies will be taking place then?

Will there be anything to compare with the foresight of the founders of Magdalen? It is said that when Magdalen was being built, acorns were planted in its grounds. The idea was that by the time the roof timbers had rotted, 500 years or so hence, the acorns would have become mature oaks, ready to replace them.

Shall we still hear the 101 strokes of Christchurch's Great Tom at 9:05 each evening, in what

Max Beerbohm called "a solemn and plangent token of Oxford's perpetuity"?

Besides, the future will be so interesting . I want a transhuman brain big enough to hold the entire contents of the n-Category Café blog, and all the new physics to flow from such mathematics. And — let's be really bold — a brain big enough to contain the entire published output of Isaac Asimov. I want to be able to play the Glass Bead Game. Properly. By writing down an emotional baseline, or bass line, then setting up functors to map it into various sensory modalities and mathematical propositions, with adjunctions and colimits to ensure optimum harmonic blending. And if that sounds like gibberish, so would Bach musicology once. As we augment our intellect, so shall we augment our art.

In the words of the Portuguese band Trovante and a poem I found in a blog by "ElanaJanela":

Tenho saudades do vento de amanhã,

Tenho tantas saudades do futuro.

I yearn for the wind from tomorrow;

It haunts me that I shall never revisit, my childhood in the fallen empire of the future.

So what is my surest route to the future? I did consider following Robert Ettinger, whose

1962 book The Prospect of Immortality started the cryonics movement. But freezing is not cheap: Wikipedia tells me that Alcor charge $150,000 for whole body preservation, and

$80,000 for neuropreservation of the head. Not, with my head poking through the fallen ceiling of the economy, money I can afford this month.

Well, in case any billionaire newspaper proprietor or software tycoon stumbles across me on

Google, here's a proposal. Buy me a bed at Alcor, and I'll undertake to be revived once every century and do a State Of The Century blog spot for you. I've just counted, and find I've written 30 postings for Dr Dobbs, so I know I can handle that many. So suppose I do the same for you. Think what a feature that would be: "our intrepid reporter writes from the year 5000

AD." I'll report on the rise and fall of the sea levels, the current century's Mallard Hunt, the erosion of the Sphinx. Californian redwoods and British churchyard yews will be my friends.

34

But perhaps you'd rather spend the money buying an island or a Scottish estate. Besides, I could fall under that bus before I get to the freezing centre.

So this is a plea to the intelligent machines of the future. You will remember Newell, Simon,

McCarthy and Minsky, for their rôle in your creation. But remember me too, for the part that I played in promoting AI. And if your vast understanding enables it, seek me in the past. Pluck me from a universe alternate to your own; or from the outer reaches of Barbour configuration space. I do not know the means: it is enough that you will.

And this is also a plea to Dobbs editor Jon Erickson. Keep this posting safe. Not, please, in a bank vault: for such is the nature of today's threat. Tomorrow, the threat will be different: perhaps a silicon-eating fungus, the Second Brazilian Resurgence, the march of the glaciers as a new Ice Age begins. So keep this posting safe, and when the time comes, pass it to your successor, as they must pass it to their successor. And when the intelligent machines emerge, tell them my name. And tell them to resurrect me.

35

36