Book - Peter Murray Scott

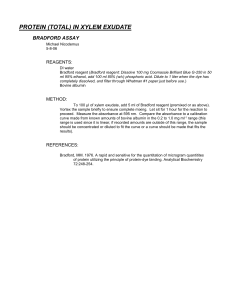

advertisement