The Rhoadales - Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research

advertisement

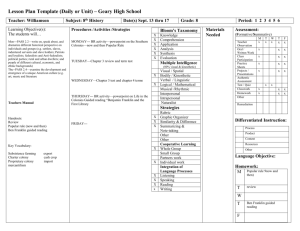

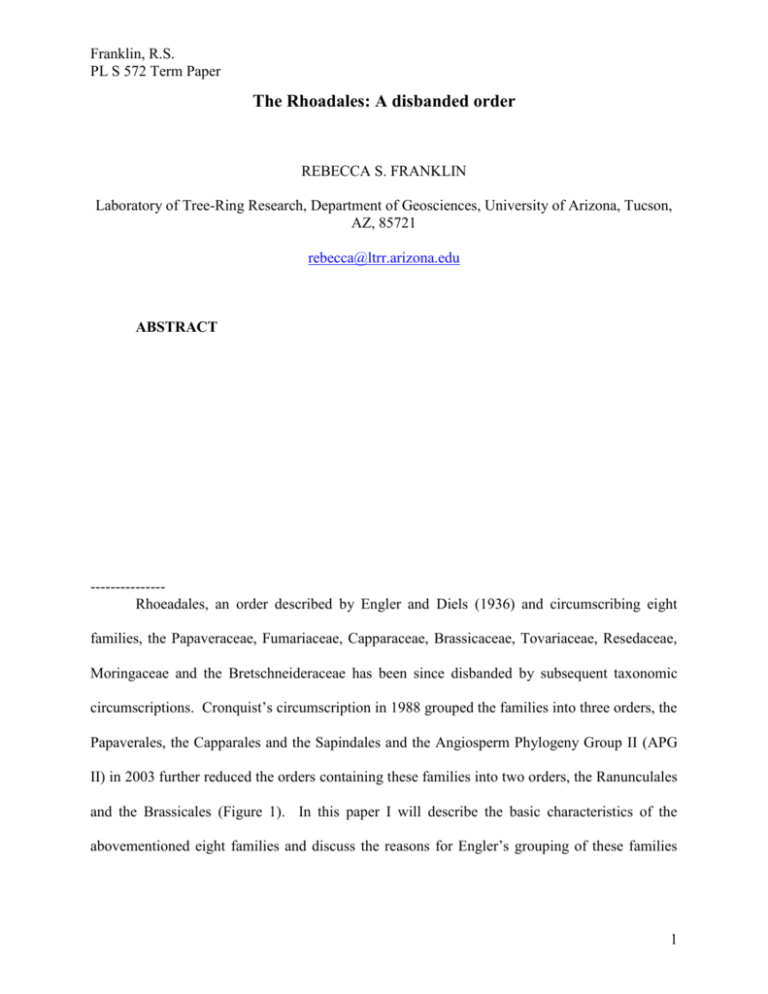

Franklin, R.S. PL S 572 Term Paper The Rhoadales: A disbanded order REBECCA S. FRANKLIN Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, 85721 rebecca@ltrr.arizona.edu ABSTRACT --------------Rhoeadales, an order described by Engler and Diels (1936) and circumscribing eight families, the Papaveraceae, Fumariaceae, Capparaceae, Brassicaceae, Tovariaceae, Resedaceae, Moringaceae and the Bretschneideraceae has been since disbanded by subsequent taxonomic circumscriptions. Cronquist’s circumscription in 1988 grouped the families into three orders, the Papaverales, the Capparales and the Sapindales and the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group II (APG II) in 2003 further reduced the orders containing these families into two orders, the Ranunculales and the Brassicales (Figure 1). In this paper I will describe the basic characteristics of the abovementioned eight families and discuss the reasons for Engler’s grouping of these families 1 Franklin, R.S. PL S 572 Term Paper into one order, the Rhoeadales, and then the reasons for the reorganization of these families in the circumscriptions of Cronquist and APG II. The first comprehensive system of plant taxonomy was Adolf Engler’s. In his book, Die Natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien (1915) he based his taxonomy of the orders and families of plants on the complexity of floral morphology. His assumptions of evolutionary trends were from simple to complex (gaining parts), free to joined, superior to inferior ovaries and actinomorphic to zygomorphic corollas. The Rhoeadales, as Engler grouped them are unified by characteristics such as leaf morphology, petal and stamen number, inflorescence type. The characteristics of the families circumscribed in Rhoeadales are as follows. I will describe characteristics that unify these families morphologically according to Engler’s circumscription into one order and also lay the groundwork for the some of the differences they have that will land them in separate orders later on. Papaveraceae Papaveraceae are herbaceous annuals or perennials that have highly dissected simple leaves that are alternalte or basal. They have showy actinomorphic flowers that are solitary to cymose and crumpled while in the bud. Two deciduous sepals are present while petals are usually four to six. The compound pistil has two to several carpels and the stigma and style are solitary. Papaveraceae have numerous hypogynous stamens, munerous ovules with parietal placentation and a superior ovary. Papaveraceae are broadly distributed throughout the northern hemisphere in subtropical environs and through the west coast of South America Fumariaceae Fumariaceae differ from the Papaveraceae in that they have only two carpels, four to six stamens (2-adelphous with two bundles of three stamens), and zygomorphic flowers with 2 Franklin, R.S. PL S 572 Term Paper distinctive two-merous dissymmetric flowers, usually spurred with a small to invisible calyx. Fumariaceae are similar to the Papaveraceae in their foliage, single to solitary inflorescences, having two sepals and the common occurrence of latex in the vegetative tissue. Capparaceae This family contains usually woody climbing plants with simple to palmately compound alternate leaves, actinomorphic to zygomorphic, perfect racemose polypetalous flowers. These plants have two to six sepals and petals. The androecium is hypogynous with six to numerous showy stamens with long filaments. The single pistil has two carpels and a distinctive superior ovary on a long gynophore. The ovary has parietal placentation, the ovules form indehiscent siliques or silicles lacking a replum, or a false septum. Capparaceae also contain mustard oils. Although having a wide distribution, these primitive plants are adapted to dry conditions in the tropics and subtropics mainly. Brassicaceae Brassicaceae differ from the Capparaceae in that they herbaceous with stellate or dendritic hairs, they have simple often highly divided leaves and their flowers are always in racemes. Additionally, the flower is always four-merous with tetradynamous stamen and the fruit always has a replum or false septum. The similarities are that Brassicaceae has mustard oils, one pistil, two carpels, a superior ovary, parietal placentation and ovules that form siliques or silicles. Distribution of Brassicaceae is world wide. The following four smaller families have a more limited tropical to subtropical distribution. Tovariaceae 3 Franklin, R.S. PL S 572 Term Paper These plants are herby to shrubby and like the above families have racemose inflorescences. They have trifoliate stipulate leaves have six- to nine-merous shortly clawed to sessile polypetalous flowers with a short style and spreading stigma. The anthers as well are sixto nine-merous and the fruit is a berry. Tovariaceae also have mustard oils. Resedaceae Resedaceae have leaves with entire to pinnatifid leaves that are alternate to spiral. These Mediterranean herbs and shrubs are usually xerophytic. The inflorescence is terminal and racemose with small zygomorphic six-merous bracteate flowers. The petals are fringed with the adaxial petal being the larest. The flowers have an obvious hypanthium three to six carpels, one ovary and locule with a capsular or berry fruit. Mustard oils are also present in this family. Moringaceae These are woody stout stemmed trees and shrubs that also contain mustard oils. Their deciduous leaves are pinnarely compound with conspicuous strongly scented glands at the base. The five-merous flowers are arranged in panicles with the floral receptacle developing a gynophore. The androecium is two whorled. Bretschneideraceae Bretschneideraceae are trees with decidous alternate pinnately compound leaves. As with many families in the Rhoeadales, they have flowers aggregated in terminal racemes. These large flowers are zygomorphic, polypetalous, with a five-merous calyx and corolla. Carpels are three to five with two to three ovules per locule. This family has eight stamens with hairy filaments. Once more mustard oils are found in this family in the Rhoeadales. The order Rhoeadales on the whole, is temperate in distribution, containing some rather primitive plants such as the Resedaceae and the Papaveraceae and some more specialized 4 Franklin, R.S. PL S 572 Term Paper species, such as those found in the Brassicaceae (Bews 1927). The morphological similarities that Engler used in delineating this order are the inflorescence structure (usually cymose or panniculate), the highly dissected simple leaves (or in some cases compound) and the numerous stamens (in most cases). Another example of what Engler used to delineate this order is the examination of the torus, or the floral receptacle and the nectary characteristics. Norris, in 1941, commented on Engler’s Rhoeadales mentioning that the floral nectarines in Rhoeadales appear to have originated independently of the other parts. He also noted that details of the vascular bundle distribution in the Rhoeadales’ torus and also the distribution of the nectarines appear to be useful in comparing taxa in this family with respect to their phylogenetic relationships. By examining this characteristic of the flower, Norris states that it appears that the Capparaceae and the Resedaceae are the most primitive families of the Rhoeadales based on the fact that they seem to come from an ancestral group that did not have connections between the nectarines and sepal and petal vascular bundles. Using this line of reasoning, he also concludes that the Papaveraceae, Fumariaceae and Brassicaceae (then called Cruciferae) were derived from ancestral groups resembling the existing Resedaceae and Capparaceae. The argument supporting Papaveraceae being relatively “new” is that it has an absence of any nectarines on its torus and therefore cannot have given rise to any of the other families in the Rhoeadales. This reasoning follows Engler’s use of parsimony in determining phylogenetic relationships. Cronquist’s circumscription In his 1988 book the evolution and Classification of Flowering Plants, Cronquist states that the method he follows is the Besseyan method which starts out with groups that have evolved the least from their ancestral prototype rather than the taxa that are the most advanced in their descent. Cronquist uses a phylogenetic approach yet classifies taxa in a way that best 5 Franklin, R.S. PL S 572 Term Paper circumscribes their similarities and differences. Cronquist does not use molecular data as he sees it as different from and more limiting than morphological data. Still, he uses chemical and microscopic data in his circumscriptions (Cronquist 1988). Cronquist groups the families of the former Rhoeadales into three orders, the Papaverales (containing Papaveraceae and Fumariaceae), the Capparales (containing Capparaceae, Brassicaceae, Tovariaceae, Resedaceae and Moringaceae) and the Sapindales (containing Brethschneideraceae). To group together the first order, the Papaverales, Cronquist uses the morphological features of 2 sepals and three-aperature pollen and also the chemical characteristics of the absence of ethereal oils and the presence of isoquinoline alkaloids. Another factor that conscribes this group is that it is of relatively recent origin compared to the rest of the former Rhoeadales families. The second family, the Capparales have a similar combination of morphological and chemical characteristics to join the families together. Families in the Capparales have compound leaves, parietal placentation and hypogynous stamens but they also have a more rigorous characteristic- the presence of glucosinolates (mustard oils). The Sapindales have a set of characteristics that only all occur together in this order. The combination of compound or cleft leaves, haplostemenous/diplostemenous androeciums well developed nectary disks, syncarpous ovaries and one to two ovules per ovary all indicate a member of the Sapindales. In these three orders we can see a progression from the wholly morphological characteristics used by Engler to circumscribe families to an inclusion of factors that increasing levels of technology allow for, such as pollen characteristics and alkaloid identification. 6 Franklin, R.S. PL S 572 Term Paper APG II 2003 Circumscription LITERATURE CITED ANGIOSPERM PHYLOGENY GROUP. 2003. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG II. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 141: 399-436. BEWS, J.W. 1927. Studies in the Ecological Evolution of the Angiosperms. New Phytologist 26 (2): 65 – 84. CRONQUIST, A. 1988. The evolution and classification of flowering plants. 2 Ed. Bronx: nd The New York Botanical Garden. ENGLER, A, and L. DIELS. 1936. Syllabus der pflanzenfamilien. Aufl. 11. Berlin: Gebrüder Borntraeger. JUDD, W. S., C. S. CAMPBELL, E. A. KELLOGG, P. F. STEVENS and M. J. DONOGHUE. 2003. Plant systematics: a phylogenetic approach. 2 Ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer nd Associates, Inc. NORRIS, T. 1941. Torus anatomy and nectary characteristics as phylogenetic criteria in the Rhoeadales. American Journal of Botany28:101 – 113. RONSE DE CRAENE L.P., T. Y. A. YANG, P. SCHOLS and E. F. SMETS. 2002. Floral anatomy and systematics of Bretschneidera (Bretschneideraceae) Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 139: 29–45. 7 Franklin, R.S. PL S 572 Term Paper Figure 1. Changing distribution of “Rhoeadales" Family Engler (1936) Cronquist (1988) APG II (2003) Papaveraceae Rhoeadales Papaverales Ranunculales Fumariaceae Rhoeadales Papaverales Ranunculales Capparidaceae (aka Cappadaceae) Rhoeadales Capparales Brassicales (in “Brassicaceae”) Brassicaceae Rhoeadales Capparales Brassicales Tovariaceae Rhoeadales Capparales Brassicales Resedaceae Rhoeadales Capparales Brassicales Moringaceae Rhoeadales Capparales Brassicales Bretschneideraceae Rhoeadales Sapindales Brassicales Figure 2. Complete families accompanying Rhoeadales distribution A Engler (1936) B. Cronquist (1988) C. APG II (2003) Rhoeadales Papaverales Ranunculales Papaveraceae Fumariaceae Papaveraceae (incl. Chelidoniaceae, Eschscholziaceae, Platystemonaceae) Fumariaceae (incl. Hypecoaceae, Pteridophyllaceae) Papaveraceae (incl. Eschscholziaceae, Hypecoaceae, Platystemonaceae) Fumariaceae Kingdoniaceae Eupteleaceae Lardizabalaceae (incl. Decaisneaceae Sargentodoxaceae, 8 Franklin, R.S. PL S 572 Term Paper Sinofranchetiaceae), Menispermaceae Berberidaceae (incl. Epimediaceae, Leonticaceae, Nandinaceae Podophyllaceae, Ranzaniaceae) Circaeasteraceae Pteridophyllaceae Ranunculaceae (incl. Glaucidiaceae, Helleboraceae, Hydrastidaceae, Thalictraceae) A. Engler (1936) cont’d Rhoeadales B. Cronqist (1998) Cont’d C. APG II (2003) cont’d Capparales Brassicales Capparadaceae Tovariaceae Akaniaceae Brassicaceae Capparaceae (incl. Cleomaceae, Koeberliniaceae, Pentadiplandraceae) Bretschneideraceae (in Akaniaceae) Tovariaceae Brassicaceae Bataceae Resedaceae Moringaceae Moringaceae Bretschneideraceae Resedaceae Brassicaceae (incl. Capparaceae, Cleomaceae, Oxystilidaceae) Caricaceae Emblingiaceae Sapindales Staphyleaceae (incl. Tapisciaceae) Melianthaceae Gyrostemonaceae Bretschneideraceae Limnanthaceae Akaniaceae Moringaceae Sapindaceae (incl. Ptaeroxylaceae) Hippocastanaceae Pentadiplandraceae Aceraceae Salvadoraceae Burseraceae Setchellanthaceae Anacardiaceae (incl. Blepharocaryaceae, Pistiaceae, Podoaceae) Julianaceae Tovariaceae Koeberliniaceae Resedaceae Tropaeolaceae Simaroubaceae (incl. Irvingiaceae, Kirkiaceae) Cneoraceae Meliaceae (incl. Aitoniaceae) Rutaceae (incl. Flindersiaceae) Zygophyllaceae (incl. Balanitaceae, Nitrariaceae, Peganaceae, Tetradiclidaceae, Tribulaceae) 9 Franklin, R.S. PL S 572 Term Paper Figure 3. APG II classification of Ranunculales 10 Franklin, R.S. PL S 572 Term Paper Figure 4. APG II classification of Brassicales 11 Franklin, R.S. PL S 572 Term Paper Figure 5. Cronquist classification v. APG II classification 12