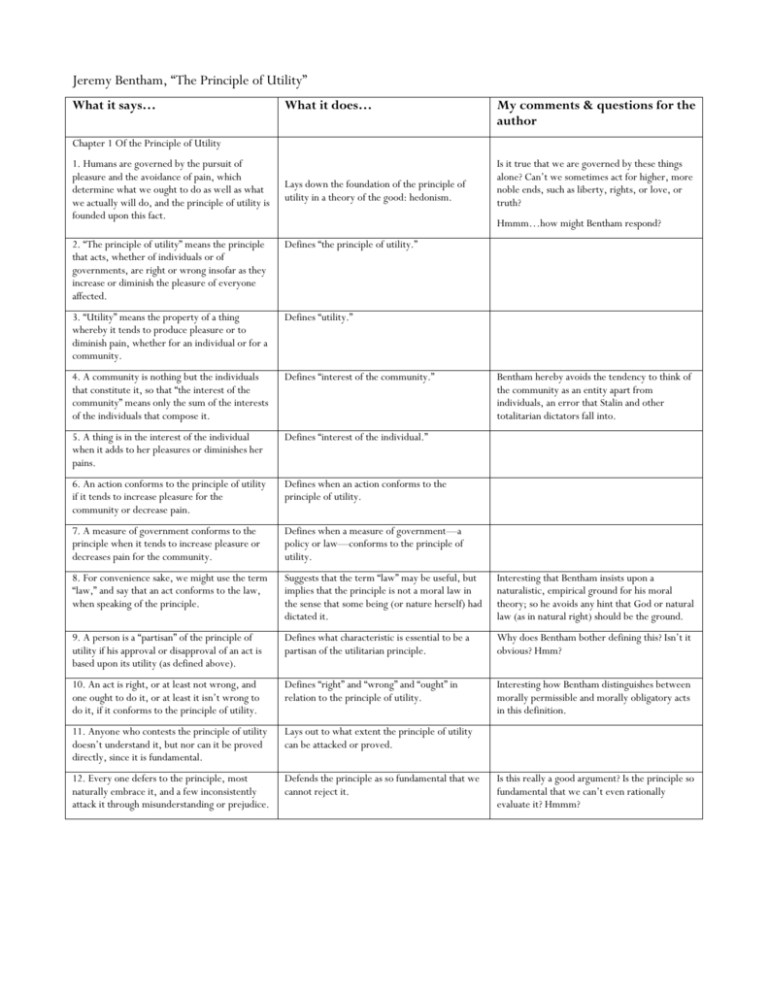

1 Jeremy Bentham, “The Principle of Utility” What it says… What it

advertisement

Jeremy Bentham, “The Principle of Utility” What it says… What it does… My comments & questions for the author Chapter 1 Of the Principle of Utility 1. Humans are governed by the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain, which determine what we ought to do as well as what we actually will do, and the principle of utility is founded upon this fact. Lays down the foundation of the principle of utility in a theory of the good: hedonism. Is it true that we are governed by these things alone? Can’t we sometimes act for higher, more noble ends, such as liberty, rights, or love, or truth? Hmmm…how might Bentham respond? 2. “The principle of utility” means the principle that acts, whether of individuals or of governments, are right or wrong insofar as they increase or diminish the pleasure of everyone affected. Defines “the principle of utility.” 3. “Utility” means the property of a thing whereby it tends to produce pleasure or to diminish pain, whether for an individual or for a community. Defines “utility.” 4. A community is nothing but the individuals that constitute it, so that “the interest of the community” means only the sum of the interests of the individuals that compose it. Defines “interest of the community.” 5. A thing is in the interest of the individual when it adds to her pleasures or diminishes her pains. Defines “interest of the individual.” 6. An action conforms to the principle of utility if it tends to increase pleasure for the community or decrease pain. Defines when an action conforms to the principle of utility. 7. A measure of government conforms to the principle when it tends to increase pleasure or decreases pain for the community. Defines when a measure of government—a policy or law—conforms to the principle of utility. 8. For convenience sake, we might use the term “law,” and say that an act conforms to the law, when speaking of the principle. Suggests that the term “law” may be useful, but implies that the principle is not a moral law in the sense that some being (or nature herself) had dictated it. Interesting that Bentham insists upon a naturalistic, empirical ground for his moral theory; so he avoids any hint that God or natural law (as in natural right) should be the ground. 9. A person is a “partisan” of the principle of utility if his approval or disapproval of an act is based upon its utility (as defined above). Defines what characteristic is essential to be a partisan of the utilitarian principle. Why does Bentham bother defining this? Isn’t it obvious? Hmm? 10. An act is right, or at least not wrong, and one ought to do it, or at least it isn’t wrong to do it, if it conforms to the principle of utility. Defines “right” and “wrong” and “ought” in relation to the principle of utility. Interesting how Bentham distinguishes between morally permissible and morally obligatory acts in this definition. 11. Anyone who contests the principle of utility doesn’t understand it, but nor can it be proved directly, since it is fundamental. Lays out to what extent the principle of utility can be attacked or proved. 12. Every one defers to the principle, most naturally embrace it, and a few inconsistently attack it through misunderstanding or prejudice. Defends the principle as so fundamental that we cannot reject it. Bentham hereby avoids the tendency to think of the community as an entity apart from individuals, an error that Stalin and other totalitarian dictators fall into. Is this really a good argument? Is the principle so fundamental that we can’t even rationally evaluate it? Hmmm?