Sociology of Human Rights

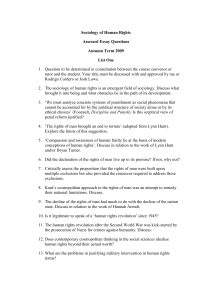

advertisement

Sociology of Human Rights 2009-10 Module Code: SO2 Website: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/sociology_of_human_rights Convenor: Professor Robert Fine Email: robert.fine@warwick.ac.uk Room: B1.37 Seminar tutor: Rodrigo Cordero Email: R.A.Cordero-Vega@warwick.ac.uk Room: R3.19 The framework of the module in ten points 1. This is a new module. Its aim is to introduce students to what is emerging as a new field in the discipline of sociology: inquiry into the idea and experience of human rights. There is a huge amount written on the topic of human rights within the disciplines of law, politics, philosophy and to a lesser extent history. There is, however, far less work on human rights that is explicitly done within the field of sociology. 2. Today human rights constitute a sub-section of law and legal scholarship in which lawyers can specialise. The normative justification of human rights has been widely discussed by philosophers and political theorists as well as lawyers. Human rights are also widely discussed by citizens as part of the cut and thrust of political argument. This module opens up the question of what role there is for sociology and social theory more broadly in understanding human rights. As for the future, my hunch is that we shall find a lot more literature with ‘sociology of human rights’ or the like in their titles. The main reason for the growing interest in the idea of human rights within sociology has to do with the changing nature of society, where it seems that human rights have become a far more prominent feature of the social and political landscape than in the past. The idea of human rights has a long prehistory – ever since legal personality became in principle a universal property of all human beings and no longer represented a privileged status opposed to that of slaves, servants and other dependents. This was a modern development and according to Hegel I one of the defining principles of modernity. 3. The pre-history of human rights was most manifest in the 18th century enlightenment when ‘natural right’ philosophies came to the fore. It was then picked up in a more political way in the declarations of the ‘rights of man’ that marked the revolutions in France, America, Poland, Haiti and doubtless other places too. There is lots of literature on the idea of the rights of man and on the role it played in relation not only to citizens but also to foreigners, blacks, slaves, women, Jews and the working class. Some of the literature emphasises the universalistic hope embodied in the rights of man; while some emphasises the silences and exclusions that were practiced and the difficulties encountered in addressing these exclusions. 4. By the pre-history of human rights I refer, then, to the emergence of the idea of the ‘rights of man’ in 18th century enlightenment thought, its application in and to the French, American and other revolutions, the exclusions and silences concealed beneath its veneer of universality, and the efforts of radical thinkers and movements to overcome these exclusions and silences and extend the rights of man to women, slaves, colonial subjects, Jews and the working class. It includes in particular the philosophical endeavour represented in Kant’s cosmopolitan writings to realise the promise of universality implicit in the idea of the rights of man and counteract the forces of nationalism and imperialism. This pre-history is important for our understanding of human rights not only because it paved the way for their development but also because the ideas of ‘human rights’ and ‘rights of man’ are too 2 often collapsed into one another. It may be more important than we think to address the distinction between them. 5. The most common narrative in historical accounts is that in the 19 th century the idea of human rights went on the back burner with the rise of nationalism, imperialism and modern forms of state power. According to this narrative human rights are a reconstruction of the rights of man, the evolution of which was halted for a couple of hundred years and only revived after the Second World War. It is said that the rights of man were a child of the 18th century but could not survive in the face of the modern bureaucratic state, colonial expansion, new forms of nationalism, antisemitism and racism, mechanised warfare and the displacement of large sections of the world population. The decline of the rights of man in the two hundred years that followed their ‘declaration’ is a crucial part of their history, though not everyone of course succumbed to the prevailing winds of nationalism. What is perhaps most notable is how far the rights of man were re-channelled into the right of nations to self-determination. 6. It wasn’t clear after 1945 whether the idea of human rights would be a 15 minute wonder expressing the aspirations of enlightened intellectuals but without any real staying power, or would become one of the enduring features of the postwar age. One might have been forgiven for thinking that the rise of human rights was merely a transitory moment of enlightenment enthusiasm since they seemed to retreat rapidly with the re-emergence of modern statism in the shape of the Cold War, anticolonial struggles in the Third World, bureaucratic domination in the Eastern bloc and social struggles for full employment and a welfare state in the Western bloc. This seemed to leave little space for the idea of human rights. To the best of my knowledge, for example, little reference was made to the idea of human rights in the context of the Vietnam War or the British war against the Mau Mau in Kenya or the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa. 7. On the other hand, the institutions and conventions of human rights and humanitarian law have taken off apace in the international arena. We need only think of the Nuremberg Tribunal (1945), the International Court of Justice (1946), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948), the European Convention on Human Rights (1950), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (from 1966), the Vienna convention on the Law of Treaties (1969), the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment (1987), the ad hoc tribunals for war crimes committed in the former Yugoslavia (1993) and Rwanda (1994), and the International Criminal Court (2002). The norms contained in these treaties, conventions and declarations are frequently broken, but what is new is that they exist. They have had a major impact on the domestic constitutions of nation states and transnational federations such as the European Union, and have been supported by civil society associations like Amnesty International. Especially since the fall of the Soviet Union and end of 3 the Cold War in 1989, it is arguable that world society cannot be understood without reference to the idea of human rights. 8. So the object of sociological knowledge we shall address is an emergent property of the modern world. Its existence is made objective in texts, treaties, conventions, constitutions, courts, social movements and NGOs. It is also present in discourses in the public sphere. The idea of human rights is not, then, a mere idea or abstract ideal, but a definite social form characteristic of our own age. The sociology of human rights is the study of this social form: its emergence and development, its uses and abuses, its functions for capitalist economy, its place within the structure of modern society as a whole. 9. It is not easy to define what sociology does in relation to human rights, which is different from what law, politics and philosophy do. What is at issue is not only a question of definition but of investigation and exploration. At the start it may be easier to say what sociology does not do. A. It is not a natural law theory that determines what human rights ought universally to be and then assesses the laws and institutions of particular societies according to this standard. B. It is not a legal positivism that simply describes or at best orders what human rights law is. C. It is not a moral philosophy designed to justify human rights or the societies that produce them. D. It is not a political realism that declares power to be the only reality and all notions of right to be illusions that ought to be dispelled. If we accept that the sociology of human rights is none of these things, we may have made our first step toward finding out what it is. 10. Sociologists and social theorists have explored such questions as the increasing centrality of human rights both in national constitutions and in expanded forms of political community such as the European Union; the application of human rights principles and laws beyond the boundaries of nation states, the responsibilities of power to prevent or stop atrocities occurring in other nation states, the constitutionalisation of international law, and the rhetoric of human rights in political argument. These substantive discussions raise historical questions about the emergence of human rights; conceptual questions concerning the relation of human rights to other forms of right, including civil, political and social rights; normative questions concerning the right of all human beings to have rights; and critical questions concerning the legitimacy of human rights. It seems to me important to draw on the resources of the sociological tradition in order to develop the sociology of human rights as a field within the larger discipline. Module requirements The module is assessed by unseen examination and / or assessed essay. Students are expected to participate in all seminars and to present, individually or jointly, at least one seminar paper in each of the first two terms. Students are expected to write at least one class essay. Students are encouraged to develop their own research interests in the area of the sociology of human rights. 4 There is no single text book for the module but among good or useful books you may wish to beg, buy or borrow are: Arendt, Hannah (1977) Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, Penguin Arendt, Hannah Arendt (1988) The Portable Hannah Arendt, Penguin, ed. Peter Baehr Baxi, Upendra (2009) The Future of Human Rights Oxford University Press Benhabib, Seyla (2004) The Rights of Others: Aliens, Residents and Citizens Cambridge University Press Bhambra, Gurminder and Shilliam, Robbie (eds) (2009) S ilencing Human Rights: Critical Engagements with a Contested Project, Palgrave Brunkhorst, Hauke (2005) Solidarity: From Civic Friendship to a Global Legal Community. MIT Press Clapham, Andrew (2007) Human Rights: A Very Short Introduction Oxford University Press Donnelly, Jack (2006) International Human Rights Westview Press Douzinas, Costas (2007) Human Rights and Empire: The Political Philosophy of Cosmopolitanism Routledge-Cavendish Fine, Robert (2007) Cosmopolitanism, London: Routledge Fine, Robert (2002) Democracy and the Rule of Law: Marx’s Critique of the Legal Form, Blackburn Press Fine, Robert (2001) Political Investigations: Hegel, Marx, Arendt Routledge Freeman, Michael (2002) Human Rights: An Interdisciplinary Approach (Key Concepts) Cambridge: Polity Habermas, Jürgen (2006) Times of Transitions Cambridge: Polity Habermas, Jürgen (2006) The Divided West Cambridge: Polity Habermas, Jürgen (2001) The Postnational Constellation, Polity Press Hirsh, David (2003) Law against Genocide: Cosmopolitan Trials, Glasshouse Press Hunt, Lynn (2007) Inventing human rights: a history, W.W. Norton, Hunt, Lynn The French Revolution and Human Rights: A Brief Documentary History (The Bedford Series in History and Culture) Palgrave MacMillan 1996. Ignatieff, Michael Human Rights as Politics and Idolatry, The University Center for Human Values Series Ishay, Micheline (2008) The History of Human Rights: From Ancient times to the Globalization Era, University of California Press. Kant, Immanuel (1991) Kant: Political Writings, Edited by Hans Reiss, Cambridge University Press Koskenniemi, Martti. 2002 The Gentle Civilizer of Nations: The Rise and Fall of International Law Hersch Lauterpacht Memorial Lectures. Cambridge University Press. Morris, Lydia (ed) (2006) Rights: Sociological Perspectives Routledge Morris, Lydia (2010 forthcoming) Asylum, Welfare and the Cosmopolitan Ideal: A Sociology of Rights, Glasshouse Press Muthu, Sankar (2003) Enlightenment against Empire Princeton University Press Sands, Philippe (2006) Lawless World: Making and Breaking Global Rules Penguin 5 Course Outline Autumn Term 2009-10 HISTORY AND THEORY WEEK 2: The Idealism of Human Rights I am going to initiate our investigation into the sociology of human rights with a discussion of the recent turn in sociology toward cosmopolitanism. The cosmopolitan imagination is important for us because the idea of human rights plays such a central role in its thinking about society. However, the cosmopolitan understanding of human rights itself splits along two paths. It appeals to the idea of human rights either to endorse what already exists or to construct a visionary programme for changing the world. Today both approaches are present in the study of human rights: one basically elevates existing human rights law into an ideal; the other turns human rights into a vision of a new world order. One is conservative and tend toward legal positivism; the other is radical and tends toward moral idealism. I shall argue that the difficulties associated with both approaches point toward an understanding of human rights that is more contradictory and sociologically grounded. Core reading Fine, Robert (2008) ‘Cosmopolitanism and human rights: radicalism in a global age’, Metaphilosophy 40(1): 8-23. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/122208363/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0 Background Baxi, Upendra (2009) The Future of Human Rights, Oxford: OUP; Chapter 1: ‘An age of human rights?’ Douzinas, Costas (2007) Human Rights and Empire: The Political Philosophy of Cosmopolitanism, London: Routledge-Cavendish; Chapter 1: ‘The end of human rights?’ Freeman, Michael (2002) Human Rights: An Interdisciplinary Approach (Key Concepts), Cambridge: Polity. Ishay, Micheline (2008) The History of Human Rights: From Ancient times to the Globalization Era, California: University of California Press; ‘Preface to the 2008 edition’ and Chapter 6: ‘Promoting human rights in the 21st century: the changing arena of struggle’. Clapham, Andrew (2007) Human Rights: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford: OUP 6 Donnelly, Jack (2006) International Human Rights (Dilemmas in World Politics), Boulder: Westview Press. Ignatieff, Michael (2001) Human Rights as Politics and Idolatry, Princeton: Princeton University Press. WEEK 3: The Realism of Human Rights The promise of universalism present in the idea of human rights seems to supersede national citizenship as the basis of rights claims and bring the idea of rights to its logical conclusion. Its understanding, however, presents peculiar difficulties for the discipline of Sociology. The overriding temptation has been toward what we might call rights-scepticism, for example, through the reduction of rights to power or the dismissal of rights as froth on the surface of society. It would appear that Sociology is uncomfortable with the concept of rights and especially with the concept of universal human rights. This scepticism has been questioned in recent sociology where the social and cultural foundations of human rights have been revisited in terms of recognition, sympathy and solidarity. Core reading Marshall, T. H. (1950) Citizenship and Social Class and Other Essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Turner, Bryan (1993) ‘Outline of a theory of human rights’, Sociology 27 (3): 489-511. http://soc.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/27/3/489 Morris, Lydia (ed.) (2006) Rights: Sociological Perspectives, London: Routledge; especially pp.1-16 and 77-93, but also articles by Elson, Busfield and Ruzza. Fine, Bob (2002) Democracy and the Rule of Law, Blackburn Press; Chapter 2: ‘Marx’s critique of classical jurisprudence’ pp. 66-85; Chapter 4: ‘Law, state and capital’ pp. 95-121; Chapter 7: ‘20th century theories’ pp. 155-189 Background reading Fine, Robert (2003) Political Investigations: Hegel, Marx, Arendt, London: Routledge; Chapter 5 ‘Right and value: the unity of Hegel and Marx’ Fine, Robert (2009) ‘Marx’s critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right’ in Andrew Chitty and Martin McIvor Karl Marx and Contemporary Philosophy, Palgrave, pp. 105-120. Bobbio, Norberto (1995) The Age of Rights, Cambridge: Polity. Morris, Lydia (2010 forthcoming) Asylum, Welfare and the Cosmopolitan Ideal: a Sociology of Rights, London: Glasshouse. Morris, Lydia (2003) ‘Managing contradiction: civic stratification and migrants’ rights’, International Migration Review 37 (1): 74-100. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30037819 7 Soysal, Yasmin (1994) Limits of Citizenship. Migrants and Postnational Membership in Europe, Chicago: Chicago University Press. Waters, Malcom (1996) ‘Human Rights and the universalisation of interests’ Sociology 30 (3): 593-600. http://soc.sagepub.com/cgi/reprint/30/3/593 Turner, 1997, ‘A neo-Hobbesian theory of human rights: a reply to Waters’, Sociology 31 (3): 565-571. http://soc.sagepub.com/cgi/reprint/31/3/565 WEEK 4: Promises, promises: Revolution and the Idea of the Rights of Man The idea of the ‘rights of man’ was a product of an 18th century international movement which called itself the Enlightenment. It then played a pivotal political role, inter alia, in the French, American and Haitian revolutions. It promised something I think was new in human history: the idea that every human being is a possessor of rights. Although the rights of man contained in practice all manner of exclusions, the universal scope of the idea prepared the ground for its extension to excluded categories: such as women, criminals, the mad, blacks, slaves, the colonised, the propertyless, Jews, etc. We shall focus, then, not only on the concept of the rights of man but also on the political practices associated with it. Finally we shall open discussion on where the idea of the rights of man went wrong: whether this was the result of external forces or something intrinsic in the idea itself. Our way into these questions is through a somewhat eccentric historical monograph by Lynn Hunt called Inventing human rights. Core reading Hunt, Lynn (2007) Inventing human rights: a history, New York: W.W. Norton; ‘Introduction’; Chapter 1: ‘Torrents of emotion: reading novels and imagining equality’; Chapter 2: ‘Bone of their bone: abolishing torture’; Chapter 3: ‘They have set a great example: declaring rights’; Chapter 4: ‘There will be no end of it: the consequences of declaring’; Chapter 5: ‘The soft power of humanity: why human rights failed, only to succeed in the long run’. Background reading Hunt, Lynn (1996) The French Revolution and Human Rights: A Brief Documentary History, Palgrave MacMillan. Muthu, Sankar (2003) Enlightenment Against Empire, Princeton: Princeton University Press; Chapter 3: ‘Diderot and the evils of empire’ pp. 72-121. Brunkhorst, Hauke (2005) Solidarity: From Civic Friendship to a Global Legal Community, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT; Chapter 3: ‘The ideas of 1789: patriotism of human rights’. 8 Bhambra, Gurminder (2007) Rethinking Modernity: Postcolonialism and the Sociological Imagination. Basingstoke: Palgrave; Chapter 5: ‘Myths of the modern nation state – the French Revolution’ Buck-Morss, Susan (2000) ‘Hegel and Haiti’, Critical Inquiry 26 (4): 821–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1344332 Kristeva, Julia (1991) Strangers to Ourselves, New York: Columbia University Press; Chapter 7: ‘On foreigners and the Enlightenment’. Foucault, Michel ‘The body of the condemned: torture’ in Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison WEEK 5: Universalising the Rights of Man: Kant’s Cosmopolitan Point of View Kant was a foremost philosopher of the last years of Enlightenment. His political essays were written late in life around the time of the French Revolution. He was alert to the national limitations of the rights of man, namely that in theory they belonged to all human beings but in practice were enforced through the nation state. Before the revolution he formulated the idea of cosmopolitan right to address this problem. After the revolution, when the rights of man had often declined into terror, militarism and nationalism, he developed this idea in a number of political essays, including ‘Perpetual peace’, and in his book The Metaphysics of Morals (section on ‘The metaphysical elements of the theory of right’). Kant’s radical thinking is now influential in current debates. His work in this area is published in Kant, Political Writings, ed. Hans Reiss (CUP) and is worth reading as a whole. Core reading Kant, Immanuel (1991) Kant: Political Writings, Edited by Hans Reiss. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ‘Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch’ pp. 93 - 130. Muthu, Sankar (2003) Enlightenment Against Empire, Princeton University Press; Chapter 5: ‘Kant’s anti-imperialism’ pp. 172-209. Background reading Fine, Robert (2007) Cosmopolitanism, London: ‘Cosmopolitanism and Natural Law: Kant and Hegel’. Routledge; Chapter 2: Benhabib, Seyla (2004) The Rights of Others, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Chapter 1: ‘On hospitality: re-reading Kant’s cosmopolitan right’. Habermas, Jürgen (1999) ‘Kant’s Idea of Perpetual Peace: At Two Hundred Years’ Historical Remove’ in J. Habermas The Inclusion of the Other: Studies in Political Theory Cambridge: MIT; and in James Bohman and Matthias Lutz-Bachmann (eds) Perpetual Peace: Essays on Kant’s Cosmopolitan Ideal Cambridge, Mass.: MIT. 9 Archibugi, Daniele (1995) ‘Immanuel Kant, cosmopolitan law and peace’, European Journal of International Relations 1 (4): 429-456. http://ejt.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/1/4/429 Cavallar, Georg (1999) Kant and the Theory and Practice of International Right, Cardiff: University of Wales Press. WEEK: 6 Reading and Researching Week Week 7 The rise and fall of the rights of man: Hannah Arendt’s genealogy After the fall of Nazism Arendt re-addressed Kant’s concerns regarding the relationship between the nation state and the rights of man in a chapter of her book on The Origins of Totalitarianism. There has been much debate around this influential work but the basic thesis is that the tensions between the universality of the idea of the rights of man and the national framework within which it is put into practice came sharply to the fore with the development of imperialism and the decline of the nation state from its original republican conception to an increasingly nationalistic practice. Arendt subsequently developed this thesis in her study of revolutions, where she argued (following Marx) that the turn to terror in the French Revolution was theoretically foreshadowed in the Rousseauian theory of the ‘general will’ that the revolutionaries reconstructed. The political implications Arendt drew from her analysis can be grasped in ‘Thought on politics and revolution’ in Crises of the Republic. Core reading Arendt, Hannah (1979) The Origins of Totalitarianism, Harcourt Brace; Chapter 9: ‘The decline of the nation state and the end of the rights of man’ pp. 267-302; extract in Peter Baehr (ed.) The Portable Hannah Arendt Penguin, 2000, pp. 31-48. Arendt, Hannah (1988) On Revolution, Harmondsworth: Penguin; Chapter 2: ‘The social question’; extract in Peter Baehr (ed) The Portable Hannah Arendt Penguin, pp. 247-277. Arendt, Hannah (1969) Crises of the Republic, ‘Thoughts on Politics and Revolution’, Harvest, pp.199-233. Background Fine, Robert (2001) Political Investigations: Hegel, Marx, Arendt. London: Routledge; Chapter 6: ‘Totalitarianism and the rational state’ and Chapter 7: ‘State and revolution revisited’. 10 Benhabib, Seyla (2004) The Rights of Others, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Chapter 2: ‘The right to have rights: Hannah Arendt on the contradictions of the nation state’, pp. 49-70. Bhambra, Gurminder and Shilliam, Robbie (eds). Silencing Human Rights: Critical Engagements with a Contested Project, London: Palgrave, pp. 1-60. Hegel, Phenomenology of Spirit, ‘Absolute freedom and terror’ Kedourie, Elie (1993) Nationalism, Oxford: Blackwell; Chapters 1 and 2. WEEK 8: The Rise and Fall of the Rights of man: A case study of the Jewish Question The so-called ‘Jewish question’ offers an interesting example of the equivocalities of the rights of man. On the one hand, the French Revolution brought about the emancipation of Jews in France – I think for the first time in Europe. On the other, the course of Jewish emancipation was extremely uneven with opposition coming both sides of the political spectrum – the Left and the Right. One of the notable features of the classics of Sociology, including Marx, is that they fought against antisemitic views of the world and sought to understand antisemitism as a misplaced radicalism closely associated with the devaluation of the rights of man. It is argued by some commentators (e.g. Altglas 2009) that resentment against Jews increased with emancipation and that this phenomenon is explicable in general sociological terms. I shall probably refresh this part of the reading list as I learn more about it. Core reading Marx, Karl ‘On the Jewish Question’ in L. Colletti (ed) Marx’s Early Writings, Penguin. Alexander, Jeffrey (2006) The Civil Sphere, Oxford University Press; Chapter 18: ‘The Jewish Question: Antisemitism and the Failure of Assimilation’. Arendt, Hannah (1979) The Origins of Totalitarianism Harcourt Brace; Chapter 1: ‘Antisemitism as an outrage to common sense’ pp. 3-10, and Chapter: 2 ‘The equivocalities of emancipation’ pp. 11-28; extracts in Peter Baehr (ed.) The Portable Hannah Arendt Penguin, 2000, pp. 75-103. Background reading Bernstein, Richard (1996) Hannah Arendt and the Jewish Question, Massachusetts, MIT; Chapter 3: ‘Statelessness and the right to have rights’. Hunt, Lynn (1996) The French Revolution and Human Rights: A Brief Documentary History, Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 48-50 and 86-100. Hertzberg, Arthur (1990) The French Enlightenment and the Jews: The Origins of Modern Antisemitism, New York: Columbia University Press; Chapter 9: ‘The men of the Enlightenment’ and Chapter 10: ‘The revolution’. 11 Traverso, Enzo (1994) The Marxists and the Jewish Question: History of a Debate 1843-1943, Humanity Books; Chapter 1: ‘Marx and Engels’ Johnson, Paul (1994) A History of the Jews, New York: Harper & Row; Chapter 5: ‘Emancipation’, pp. 341-357 Carlebach, Julius (1978) Karl Marx and the Radical Critique of Judaism, Littman Library of Jewish Civilisation; Chapter 7: ‘The radical challenge to Jews’ and Chapter 8: ‘The Marxian response’, pp. 125-186 WEEK 8: Punishing Crimes Against Humanity: The Beginnings of the Human Rights Revolution? The human rights revolution was kick-started in the course of the Second World War by responses to the experience of Nazism (and to a lesser extent Stalinism). Amongst the first manifestations of this revolution was the establishment of crimes against humanity as an offence in international law that enabled the prosecution of heads of state for crimes for crimes that violate the conscience of humanity – even if they are legal in terms of domestic laws. The conception of the idea of ‘genocide’ and then the passing of the Genocide Convention were roughly coeval developments. These innovations, which were triggered in part by the Holocaust, broke new ground inasmuch as they sought to make human rights into something tangible that no power could overrule with impunity. The rise of this human rights framework is explored through the legacy of the Nuremberg Tribunal and then the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. However, the development of the Cold War and of new forms of nationalism place a question mark over how far it succeeded in holding accountable the most violent abuses of power. We shall take off again from a reading of the work of Hannah Arendt. Core reading Arendt, Hannah (1977) Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, Harmondsworth: Penguin; Chapter 15: ‘Judgment, appeal, execution’ pp. 234-252; ‘Epilogue’ pp. 253-279 Arendt, Hannah (2005) Essays in Understanding, 1930-1954: Formation, Exile, and Totalitarianism, New York: Schocken; ‘Organised guilt and universal responsibility’ and ‘The aftermath of Nazi rule’. Background reading Fine, Robert (2007), Cosmopolitanism, London: Routledge; Chapter 6: ‘Cosmopolitanism and punishment’. 12 Fine, Robert (2000) ‘Crimes against humanity: Hannah Arendt and the Nuremberg Debates’, European Journal of Social Theory 3(3): 293-311. http://est.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/3/3/293 Fine, Robert (2001), ‘Understanding evil: Arendt and the final solution’ in Maria Pia Lara (ed.) Rethinking Evil: Contemporary Perspectives, LA: University of California Press, pp. 131-150 Fine, Robert and Hirsh, David (2000) ‘The decision to commit a crime against humanity’, in Margaret Archer and Jonathan Tritter (eds) Rational Choice Theory: Resisting Colonisation, London: Routledge. Jaspers, Karl (1961) The Question of German Guilt, New York: Capricorn. Jaspers, Karl (2006) ‘Who should have tried Eichmann?’, Journal of International Criminal Justice, 4 (4): 853-858. http://jicj.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/4/4/853 Norrie, Alan (2008) ‘Justice on the Slaughter-Bench: The Problem Of War Guilt In Arendt And Jaspers’, New Criminal Law Review 11(2): 187-231. http://0heinonline.org.pugwash.lib.warwick.ac.uk/HOL/Page?collection=journals&handle=h ein.journals/bufcr11&id=191 Douglas, Lawrence (2001) The Memory of Judgement: Making Law and History in the Trials of the Holocaust, New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Deak, Istvan (1993) ‘Misjudgment at Nuremberg’’, New York Review of Books, 7 October pp. 46-52. Kirchheimer, Otto (1969) Political Justice, Princeton: Princeton University Press. Mazower, Mark (1998) The Dark Continent: Europe’s 20th Century Harmondsworth: Penguin; Chapter 6: ‘Blueprints for the golden age’, pp. 184214 Levy, Daniel and Sznaider, Natan (2002) ‘Memory Unbound. The Holocaust and the formation of Cosmopolitan Memory’, European Journal of Social Theory 5 (1): 87106. http://est.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/5/1/87 WEEK 9: From Human Rights to Humanitarian Military Intervention: The Cosmopolitan Vision of Jürgen Habermas No social theorist has sought to explore the ramifications of the human rights revolution with as much rigour and imagination as Jürgen Habermas. He has traced the increasing centrality of rights in domestic constitutions in a theory of ‘constitutional patriotism; the expansion of this theory beyond the boundaries of the nation state in his work on the postnational constellation and particularly on the problems facing the new Europe; the application of human rights beyond the boundaries of the nation state in his discussion of the responsibilities of power to prevent or stop atrocities occurring in other states; and the theorisation of human rights in his discussion of the constitutionalisation of international law. No one can begin to address this topic now without coming to terms with his work. We shall 13 touch on some aspects of this voluminous work, in particular the uses and abuses of human rights in addressing the question of humanitarian military intervention and the rhetoric of human rights and humanitarian law in current political argument. Core reading Habermas, Jürgen (1999) ‘Bestiality and Humanity: A war on the border between legality and morality’, Constellations 6 (3): 263-72. http://0www3.interscience.wiley.com.pugwash.lib.warwick.ac.uk/cgibin/fulltext/119088507/PDFSTART Habermas, Jürgen (2006) The Divided West, Cambridge: Polity, Chapters 1 and 2 pp. 1-36 and Chapter 8: ‘Does the constitutionalisation of international law still have a chance?’ Background reading Habermas, Jürgen (2006) The Postnational Constellation, Cambridge: Polity Habermas, Jürgen (2006) Time of transitions, Cambridge: Polity; Chapter 2: ‘From power politics to cosmopolitan society’ pp. 19-30 Habermas, Jürgen (2003) Philosophy in a Time of Terror: Dialogues with Jürgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida, ed. Giovanna Borradori, Chicago: University of Chicago Fine, Robert (2007) Cosmopolitanism, London: Routledge; Chapter 3: ‘Cosmopolitanism and political community’; Chapter 4: ‘Cosmopolitanism and international law’; Chapter 5: ’Cosmopolitanism and humanitarian military intervention’, pp.39-95. Rawls, John (1999) The Law of Peoples, London: Harvard University Press. Pogge, Thomas (2001) ‘Rawls on International Justice’, The Philosophical Quarterly, 51(203): 246-253. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2660572 Bohman, J. 2007. Democracy Across Borders: From Demos to Demoi. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Benhabib, Seyla (2004) The Rights of Others, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Chapter 3: ‘The Law of Peoples, distributive justice, and migrations’. WEEK 10 Revision, catching up, questions, discussion of research, essay writing, where are we now. 14 Spring Term 2010 CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN THE SOCIOLOGY OF HUMAN RIGHTS **This is a highly provisional reading list for the second term. The focus will be on contemporary issues and will be finalised in the course of the first term** WEEK 1: Is There a Crisis of Human Rights? Thinking with Hauke Brunkhorst Hauke Brunkhorst argues that there is currently emerging a legitimacy crisis of human rights. We shall look at his rich and interesting argument. Core reading Brunkhorst, Hauke “Cosmopolitanism and Democratic Freedom.” Paper presented at Onati Institute for Sociology of Law conference “Normative and Sociological Approaches to Legality and Legitimacy,” 24– 25 April, 2008 WEEK 2: Is there a ‘Responsibility to Protect’ and if there is, whose responsibility is it? State power and Humanitarian Military Intervention Core reading Young, Iris Marion (2003) ‘Violence Against Power: Critical Thoughts on Military Intervention’ in D. K. Chatterjee and D. E. Scheid (eds.) Ethics and Foreign Intervention, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Smith, William (2007) 'Anticipating a Cosmopolitan Future: The Case of Humanitarian Military Intervention', International Politics, 44 (1): 72-89. http://0-www.palgravejournals.com.pugwash.lib.warwick.ac.uk/ip/journal/v44/n1/pdf/8800159a.pdf Background reading Ferrara, Alessandro The Force of the Example: Explorations in the Paradigm of Judgment, New York: Columbia University Press; Chapter 7: ‘Enforcing human rights between Westphalia and cosmopolis’ Zolo, Danilo (2002) Invoking Humanity: War, Law and Global Order, London: Continuum. Wheeler, Nicholas. (2000) Saving Strangers: Humanitarian Intervention in International Society, Oxford, Oxford University Press. Roth, K. (2004) ‘War in Iraq: Not a Humanitarian Intervention’, Human Rights Watch, http://hrw.org/wr2k4/download/3.pdf 15 Walzer, Michael (2000) Just and Unjust Wars New York: Basic Books. Krisch, Nico (2002) ‘Legality, Morality and the Dilemma of Humanitarian Interventions after Kosovo’, European Journal of International Law 13 (1): 323-335. http://ejil.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/13/1/323 Falk, Richard (1999) ‘Kosovo, World Order, and the Future of International Law’, American Journal of International Law 93 (4): 847-857. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2555350 Brown, Chris (2003) ‘Selective Humanitarianism: In Defence of Inconsistency’, in D. K. Chatterjee and D. E. Scheid (eds.) Ethics and Foreign Intervention, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Booth, Ken (2001) ‘Ten Flaws of Just Wars’ in K. Booth (ed.) The Kosovo Tragedy: The Human Rights Dimension, London: Frank Cass. Archibugi, Daniele (2004) ‘Cosmopolitan Guidelines for Humanitarian Intervention’, Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 29 (1): 1-22. http://www.danielearchibugi.org/downloads/papers/Humanitarian_intervention.PDF Fine, Robert (2007) Cosmopolitanism, London: Routledge; Chapter 5: ‘Cosmopolitanism and humanitarian military intervention’, pp. 78-95 WEEK 3: Should Tyrants be Prosecuted? State Power and International Criminal Justice Core reading Hirsh, David (2003) Law against Genocide: Cosmopolitan Trials, Glasshouse Press; Chapter 4: ‘Peace, security and justice in the former Yugoslavia’ and Chapter 5: ‘The trials of Blaskic and Tadic at the ICTY’. Koskenniemi, Martti (2002) ‘Between impunity and show trials’, Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations Law 6(1): 1-32 www.mpil.de/shared/data/pdf/pdfmpunyb/koskenniemi_6.pdf Background reading Robertson, Geoffrey (2006) Crimes against Humanity: The Struggle for Global Justice Harmondsworth: Penguin Sands, Philippe ed. (2003) From Nuremberg to the Hague: the Future of International Criminal Justice, Cambridge: CUP May, Larry (2005) Crimes against Humanity: a Normative Account, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. May, Larry (2006) ‘Crimes against humanity’ Ethics and International Relations 16 WEEK 4: How Does International Law Work? The Dialectics of Law and Power Core reading Koskenniemi, Martti (2009) ‘Miserable Comforters: International Relations as New Natural Law’, European Journal of International Relations 15(3): 395–422. http://ejt.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/15/3/395 Fine, Robert (2010) ‘Political argument and the legitimacy of international law: A case of distorted modernisation?’ in Chris Thornhill and Samantha Ashenden (eds) Normative and Sociological Approaches to Legality and Legitimacy. Background reading Krisch, Nico (2004). “Imperial International Law”, Global Law Working Paper 01/04. http://www.law.nyu.edu/global/workingpapers/2004/ECM_DLV_015797 Koskenniemi, Martti (2001) The Gentle Civilizer of Nations: The Rise and Fall of International Law, 18 70–1960, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Sands, Philippe (2006) Lawless World: Making and Breaking Global Rules. Harmondsworth: Penguin Bowring, Bill (2008) The Degradation of the International Legal Order: The Rehabilitation of Law and the Possibility of Politics. London: Glasshouse. 2008 Miéville, China (2005) Between Equal Rights: A Marxist Theory of International Law, Leiden: Brill. Kumm, M (2004) ‘The Legitimacy of International Law: A Constitutionalist Framework of Analysis’, European Journal of International Law 15(5): 907- 931. http://ejil.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/15/5/907 Zolo, Danilo (2002) ‘A Cosmopolitan Philosophy of International Law? A Realist Approach’, Ratio Juris 12 (4): 429–44. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/119083202/abstract Anghie, Antony (2004) Imperialism, Sovereignty and the Making of International Law Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. WEEK 5: Human Rights and Empire: The Dialectics of Universality and Difference Core reading Kapur, Ratna (2005) Erotic Justice: Law and the New Politics of Postcolonialism, Glasshouse Press; Chapter 4: ‘The tragedy of victimisation 17 rhetoric: resurrecting the ‘native ‘ subject in international / postcolonial feminist legal politics’ Background reading Kapur, op.cit; Chapter 5: ‘The other side of universality: cross-border movements and the transnational migrant subject’ Ferrara, Alessandro The Force of the Example: Explorations in the Paradigm of Judgment, New York: Columbia University Press; Chapter 6: ‘Exemplarity and human rights’ WEEK 6: Reading and Researching Week WEEK 7: The Politics of Human Rights: A Case Study of the Israel-Palestine Conflict Core reading Habibi, Don (2007) ‘Human Rights and Politicised Human Rights: A Utilitarian Critique’, Journal of Human Rights 6(1):3–35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14754830601098410 Background reading Cocks, Joan (2009) ‘Is the right of sovereignty a human right? The idea of sovereign freedom and the Jewish state’, in Gurminder Bhambra and Robbie Shilliam (eds) Silencing Human Rights: Critical Engagements with a Contested Project, Palgrave WEEK 8: Critical Criticism and Human Rights Core reading Douzinas, Costas (2007) Human Rights and Empire: The Political Philosophy of Cosmopolitanism, London: Routledge-Cavendish. Background reading Agamben, Giorgio (1998) Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Balibar, Etienne (2004) ‘Is a Philosophy of Human Civic Rights Possible?’, South Atlantic Quarterly 103 (2–3): 311–22. 18 http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/south_atlantic_quarterly/v103/103.2balibar.h tml Zizek, Slavoj (2005) ‘The Obscenity of Human Rights: Violence as Symptom’, http://www.lacan.com/zizviol.htm Rancière, Jacques (2004) ‘Who is the subject of the rights of man?’, South Atlantic Quarterly 103 (2–3): 297-310. http://saq.dukejournals.org/cgi/reprint/103/23/297 Douzinas, Costas (2000) The End of Human Rights: Critical legal thought at the end of the century, Oxford: Hart Zizek, Slavoj (2005) ‘Against Human Rights’ New Left Review 34 (July–August). http://www.newleftreview.org/?getpdf=NLR26805&pdflang=en WEEK 9: Critical Theory and Human Rights: The (Lost) Legacy of Marx Core reading Fine, Bob (2002) Democracy and the Rule of Law , Blackburn Press; Chapter 2: ‘Marx’s critique of classical jurisprudence’ pp. 66-85; Chapter 4: ‘Law, state and capital’ pp. 95-121; Chapter 7: ‘20th century theories’ pp. 155-189 Fine, Robert (2009) ‘Marx’s critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right’ in Andrew Chitty and Martin McIvor, Karl Marx and Contemporary Philosophy, Palgrave, pp. 105-120. Background reading Fine, Robert (2003) Political Investigations: Hegel, Marx, Arendt, London: Routledge; Chapter 5: ‘Right and value: the unity of Hegel and Marx’ Pashukanis, Evgeni (1989) Law and Marxism: A General Theory, London: Pluto. Also available at: http://www.marxists.org/archive/pashukanis/1924/law/index.htm Baynes, K (2000) ‘Rights as Critique and the Critique of Rights: Karl Marx, Wendy Brown and the Social Function of Rights’, Political Theory 28(4): 451-468. http://ptx.sagepub.com/cgi/reprint/28/4/451 Benton, Ted (2006). ‘Do we need rights? If so, what sort’ in Morris, Lydia (ed) Rights: Sociological Perspectives, London: Routledge pp. 21-36 19 Summer Term 2010 WEEK 1: Toward a Social Theory of Human Rights: An Open Discussion WEEK 2: Revision Class WEEK 3: Revision Class 20