Mystery of the Megaflood

advertisement

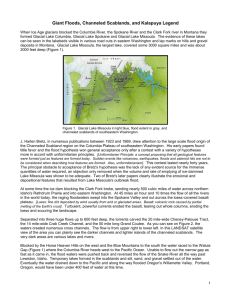

Mystery of the Megaflood The peaceful flat farmland of Washington State, but after hundreds of miles it changes and in the distance a very different landscape appears: gorges some almost 1000 feet deep a waterfall five times wider than Niagara, without any water, weird holes in the valley floors, strange layers of silt and ash, and over the whole area huge boulders are scattered as if a giant had dropped them there. Few places on Earth are as mysterious and controversial as the channeled scablands that lay just 200 miles east of Seattle. For over a century scientists have been struggling to explain what forces could have shaped this unique place. But for much of that time they were unable to account for it. Vic Baker, University of Arizona speaking: “When we see a landform or group of landforms we relay upon our knowledge as to how similar landforms were created. So the geologist is always thinking of the origin of a particular feature. However, there was one landscape that really defied the understanding of geologists, and, of course, that landscape was the channeled scablands” Then a series of clues began to fit together to finally explain this bizarre landscape. And it came about through the study of rocks. Baker speaking: “In geology we are really looking for evidence, for features in the rocks on the landscape. It’s very similar to what a detective does looking for clues at a crime scene. And those clues are fit into a pattern and ultimately a culprit is associated with that crime scene.” Baker in helicopter: “It’s wonderful to be flying over one of the most interesting parts of the United States. Even the first explorers and first settlers who came into this area recognized this as truly remarkable topography, and they realized that this was something line the Earth having been subjected to wounds and sores, so they called this ‘scablands.’ But you can’t really get a sense of the scale of this unless you get out onto the land itself.” For a long time it was assumed that the scablands features would have taken millions of years to create. One obvious way this could have happened is by the gradual erosion caused by rivers. After all, some of the most dramatic landscapes in the world have been scoured out by rivers. Kathleen Nicoll, University of Oxford speaking: “A lot of the features in this valley do appear, at first site, to be related to rivers that may have come through the valley.” But some features require fast and violent river action. While others like this huge hill of gravel appear to have been laid down by large, slow moving rivers over millions of years. And these mysterious layers look like the result of a giant river flooding again and again. Nicoll speaking: “And that’s actually really what’s been puzzling geologists. How could a river have deposited those features and yet carved out such a wide and deep and long and shear canyon?” The rivers and lakes in the scablands today could not have sculpted this landscape. This water is part of a modern irrigation system and was not here when the scablands were created. The only river big enough and old enough is the Columbia, which is 50 miles away. And there is no evidence that it ever flowed through the scablands. But there is another reason to rule rivers out. No river in the world can form what you are about to see. You will not find these anywhere else on Earth. These enormous potholes are one of the strangest geological features on Earth. Baker speaking: “If I was on the bottom of a big river like the Columbia, I might find some potholes that were maybe a few feet across, a few feet deep. But this feature, this rock basin, of which there are hundreds in the channeled scablands, is about ten times as big as the potholes that we find in even a large river like the Columbia. It’s really very clear just from the size of the features that this was not made by normal river processes.” This revelation turned the scablands into one of the most perplexing geological mysteries. But if not rivers, then what formed this landscape? Boulders like this one pointed to another possible culprit. How could this 100-ton giant have been dumped on the edge of this thousand foot precipice? It’s made of granite, and granite is not native to the scablands. But granite boulders of many different sizes are scattered erratically throughout the area. Indeed, they are known as Erratics. There is one force on Earth that could put this boulder up here, and it is not a river. It is something else. Ice. Ice can carve through solid rock and can help build mountains. Twenty thousand years ago during the last ice age massive sheets of slow moving ice, called glaciers, push gradually down from Canada towards the scablands. Glaciers moved down valleys carving out new landscapes as they go. They rip out rocks on the valley floor, and these erratics then travel within the ice, sometimes for hundreds of miles until they are left behind when the ice melts. But erratics were not the only clues pointing to glaciers. When a glacier carves out a canyon, it cuts through lots of little valleys on either side, leaving them hanging far above the main valley floor. Baker speaking: “There are some classic glacial-like features. On the ridge on the horizon there are hanging valleys where the cliff cuts a depression. In glaciation, the glacier enters a valley, it enlarges it and it cuts off the tributaries leaving them hanging. So, it was natural to have as the hypothesis that glaciation may be the origin of some of these large features of the channeled scablands.” Yet again, it looked as if the culprit had been found. Surely, glaciers working over thousands of years must have created this strange landscape. But, there was a problem. The ice sheets that flowed down from Canada during the last ice age never reached the scablands. So the two main theories to explain the gradual formation of this landscape just didn’t work. River erosion could not explain giant potholes and ice was too remote from the scabland to create these hanging valleys. Geologists, it seamed, were back where they had started. Each time they attempted to explain the riddle of this tantalizing landscape, they failed. There was, however, one last theory that claimed to offer an answer. Unfortunately, it struck those who first heard it as completely outrageous. During the 1920s, a geologist named J. Harlan Bretz outlined a theory of what he thought had happened to the scablands. But Bretz’s theory defied all scientific convention. He claimed the scablands were not the result of a slow geological evolution, but of an enormous catastrophe that had happened almost over night. For years Bretz traveled the scablands examining the landscape. Eventually one feature would clinch his argument, although it would take him decades to recognize it. From ground level, these shapes don’t make much sense. Richard Waitt, United States Geological Survey: “Bretz must have walked over thousands of those things, but they are so big; in the field he just didn’t know what they were; he didn’t guess what they were.” Bretz would not see aerial photographs of these hills for many years. But we can see from the air how these shapes begin to look like ripples, a giant version of the ripples left behind on the beach by the sea. Even without this key observation, the years Bretz spent patiently examining rocks and other features of the scablands convinced him only a vast volume of water could account for all the evidence. In his mind the entire landscape, which had once been a flat plateau, was created in a single giant flood. But as Bretz well knew his geological colleagues, understanding that the Earth was billions of years old, firmly believed that landscape such as the scablands must have gradually formed over long periods of time. It was this orthodox view that Bretz now seemed to be challenging. S Waitt speaking: “Since the 1820s geologists had come to think, on good evidence, that most landforms and most deposits on Earth had formed over long period of time by ordinary processes of rivers and ocean waves and what have you. Bretz comes and offers this immense catastrophe altering the landscape essentially over night. And it just didn’t square with the way geology had been put together at the time.” On the 12th of January 1927, Bretz prepared to address a specially convened meeting of fellow scientists in Washington D.C. This was his big chance to sell his outlandish theory. [Gavel banging then someone says: “The four-hundred-twenty-third meeting of the National Geological Society of Washington is now called to order.”] Bretz was proposing something completely unheard of: a body of water up to 900 feet deep raging through the scablands and then flowing off into the Pacific Ocean. Actor Bretz speaking: “Over 500 cubic miles of water, great flow depths; now, no gradual process is responsible for this landscape. I am forced by the field evidence by what I have observed with my own eyes to come to this hypothesis.” Another actor speaking: “It is clear from my field evidence that the Columbia River, swollen in size, could easily have cut Dry Falls., and deposited” [fade out here as narrator begins again] To any self respecting geologist, this sounded too much like a biblical flood. They dismissed Bretz out of hand. Non-Bretz actor speaking: “This did not happen over night, but over many thousands of years. To suggest otherwise is ludicrous.” Baker speaking: “The implication was, very clearly, that Bretz was committing a kind of heresy; and, that he should listen to these elder statesmen of the science and rethink his hypothesis.” Even if you were convinced by his unbelievable idea Bretz still had a problem. Waitt speaking: “Where did the water come from? And Bretz can’t tell them where the water came from. It’s one of the big problems with the whole idea.” To convince his colleagues, Bretz needed a source. How could so much water, traveling at ferocious speeds suddenly appear out of thin air? No one among the top geologists gathered that day could imagine the source for this heretical flood . . . well, almost no one. Waitt speaking: “Sitting in the audience is J. T. Pardee. Pardee supposedly leans over to a colleague and says ‘I know where Bretz’s water came from.’” But it will be more than a decade before Pardee reveals his secret. During that time, Bretz remained firmly in the geological wilderness. But, Bretz would not give up and his theory would return again to take the world of geology by storm. This is Missoula, Montana. It lies 250 miles east of the scablands. Few who live here would ever suspect that this place was once the center of an epic confrontation between water and ice. The sheer scale of this confrontation is hard to imaging. But evidence of its true extent lies scattered on hill sides for miles around. For a long time, no one could work out what made these marks. It was only when geologists discovered some scrapings on a rock that an unusual idea unexpectedly emerged. Roy Breckenridge, Idaho Geological Society speaking: “These marks, scratches as it were, on the bedrock represent the erosion of a large glacier that moved into this valley.” This evidence gave rise to the possibility that the glacier created a lake by damming a river. These water marks were formed by the waves of the lake splashing against the shoreline of these hills. This glacier came from Canada during the last ice age to reach what is now Idaho. Breckenridge speaking: “Looking at a larger scale, the ice moved down the valley from Canada and filled this whole valley from one side to another. It ran into the mountain in front of us and thus blocked the river valley up to the left.” Clark Fork River, which still runs through this valley, confronted a wall of ice that was half a mile high and an amazing 23 miles wide. The river began to back up against this wall of ice and fill the valley with water. Eventually a lake of trapped water grew bigger than Lakes Erie and Ontario combined. It was this lake that made these water marks. And, if it were still here today it would drown Missoula, Montana in well over one thousand feet of water. The volume of water backed up behind the ice was vast, an astounding 520 cubic miles of water that became known to geologists as Glacial Lake Missoula. This valley was once the bottom of Glacial Lake Missoula and it holds vital clues to solving the mystery of the scablands. But what could it have to do with a place that is 250 miles away? It was here in this valley, that Joseph T. Pardee, the man who didn’t speak at Bretz’s meeting, made an important discovery. He knew from the water marks that there was once an enormous lake here. But, there was no evidence that it had ever been anything but static until he noticed these ripples. Waitt speaking: “Those are huge ripples, like ripples on the floor of a stream, but here instead of being inches high they are 10-, 20-, 30-, 40-feet high and spaced 200-, 300-feet apart; they are enormous.” It was when he saw these ripples that Pardee came up with his own extraordinary theory. He proposed that Lake Missoula had somehow emptied and as it poured out the lake water pushed up the gravel on the valley floor to create these giant ripples. Waitt speaking: “He looks around and sees these other things that go with it. There is that great bar of gravel with the steep front to it; there is a path up there that is sharply eroded; there are these rocks all over the ripples that indicate high speed of current.” And there was something else about the ripples that Pardee noticed. They seemed to point straight towards the scablands. Waitt speaking: “Here is a huge body of water and it is just charging at a fantastic rate right towards Bretz’s channeled scablands.” Pardee’s discovery of the ripples was crucial. At last he had come up with a possible source for Bretz’s giant flood. But there was one question that he and his colleagues couldn’t answer: what caused the lake to empty in the first place? Vital clues would eventually come from three thousand miles away, in another extraordinary landscape. This is Iceland, one of the world’s most geologically active land masses, constantly rocked by earthquakes and volcanic activity. This island on the northwestern tip of Europe is home to strange lava-filled formations and it also has more glaciers than all of those in Europe put together. Matthew Roberts-Worth, examining glaciers for the Icelandic Geological Office, has cast a whole new life of Glacial Lake Missoula and its disappearing water. What you are looking at now is a modern day wall of ice; it is the head of a glacier, a smaller one that created Lake Missoula over 15,000 years ago. Matthew Roberts speaking: “This glacier is massive; it is about 300 feet thick, but that is tiny to the glacier that formed Glacial Lake Missoula, which was at least ten times thicker. In this example here, the ice has flowed across the valley to the other side forming a plug; this is exactly the same setting as what would have occurred at Glacial Lake Missoula.” When glacial ice blocks the flow of a river and water builds up behind the ice, scientists call it pen-ice dam. From his work studying ice dams here, Matthew Roberts and his colleagues have come up with a extraordinary explanation for how Glacial Lake Missoula might have emptied. It has to do with what goes on inside deep within these enormous mountains of ice. His theory is based on data from seismometers which monitor tiny ice cracks opening hundreds of feet deep inside this massive glacier. Roberts speaking: “These cracks signify that the glacier is behaving in a brittle matter as the ice is fracturing. Just like the fracture that we see behind us here, this crevice has opened up due stresses inside the ice and the crack is heard by the seismometers.” Matthew Roberts was driven to do this work not by an interest in Lake Missoula, but by an urgent need to understand the disaster that happened on his own doorstep. In 1996, a wall of water cascaded through southern Iceland causing incredible devastation. It was the result of an ice dam collapsing. After years of analysis, Matthew eventually worked out the process that caused the dam to fail. Normally, water freezes at zero degrees centigrade and forms ice. But deep at the base of an ice dam, the sheer amount of pressure stops the water molecules from expanding. If the cannot expand then the water cannot freeze. This results in what is called super cooled water, which can stay liquid several degrees below freezing. Then the highly pressurized super cooled water begins to force its way into tiny cracks in the ice. Water under this much pressure behaves in some very unexpected ways, especially in such intimate contact with ice. This is the first small step in a chain of events that can end in cataclysm. Once super cooled water has begun to trickle through these cracks, the flowing water alone is enough to trigger a very peculiar process. This moving water creates tiny amount of friction. This friction releases energy in the form of heat. As the water moves through the glacier, it melts the ice. Soon minute cracks can become giant ones several feet across. Roberts speaking: “More water can escape, the tunnel enlarges very quickly, but then suddenly the dam would have failed and BANG the whole dam would have collapsed and a massive wall of water kilometers wide would have swept down the valley.” This process caused the 1996 Icelandic flood. Scientists now believe that it was responsible for what happened thousands of years ago at Glacial Lake Missoula when a half-mile of ice suddenly collapsed allowing the entire lake to empty. From these new finding we can reconstruct just how Glacial Lake Missoula sent two and a half trillion tons on water, nearly half of Lake Michigan, surging across the American northwest. First, river water built up for years behind the ice dam. Then, as it reached depths of several thousand feet, the pressure grew forcing molecules of super cooled water into cracks at the base of the Glacial Lake Missoula ice dam. What started as a new trickle of water quickly hollowed out a series of tunnels in the ice that fatally destabilized the whole structure. Then as the sear weight of water became too much the ice dam literally exploded, leaving a gaping hole a mile or more wide through which a sea of lake water erupted. Waitt speaking: “You would have heard this tremendous roar coming long before you saw anything; the ground would have shook.” Roberts speaking: “Imagine the loudest noise you have ever heard and multiply that by a thousand times.” The sheer speed and volume of this incredible mass of water turned up those huge ripples and left behind water marks as a record of its vast size. The one cataclysmic event sent trillions of water at ferocious speeds towards the scablands. This is how scientists believe the ice dam collapsed and how Glacial Lake Missoula emptied. But could this single event have created all the extraordinary features in the scablands? How could a rushing mass of water create canyons that look as if they had been eroded over millions of years like this one known as Dry Falls, twenty times the size of Niagara Falls? How could water transport these giant erratics that are normally carved out by glaciers? And how could it form these giant potholes found here on such a monumental scale? To test whether a single flood coming form Lake Missoula could have really done all this, scientists have built their own mini scablands. Here, the Earth Surface Dynamics team at the University of Minnesota has constructed a scale model of the scablands and poured water over it to represent the failure of Glacial Lake Missoula. Team member says: “Here it comes.” The rushing water doesn’t simple disperse over a wide area it gouges out channels and then erodes them into extraordinary shapes. It is only when the water is turned off that the significance of these shapes becomes clear. Team member: “We are seeing the same essential set of processes. In fact, it is one of the remarkable things about these natural systems is that the same fundamental sets of processes can occur across a very wide range of scale; they are what we call scale independent.” For years scientists argued that the features of the scablands could not have been formed overnight. But, this model clearly shows miniature versions of the canyons found in the scablands. Just like the real ones, they look as if they were gradually eroded. In fact, they were carved out in seconds. But can the scientists also show how these strange potholes were made? This water tunnel demonstrates the effects of water moving at high speed. An object in the tunnel represents a hard outcrop of rock. At first the water flows around the object without any apparent effect. But then they turn up the speed. A stream of minute bubbles appears. When those bubbles burst they burst with immense force against the object. As the speed of water increases further the bubbles collapse with ever greater intensity. The process slowed down nearly a hundred times reveals a long twisting thread emerging from the metal object. It is in this high speed vortex of bubbles where the secret to the flood’s incredible power lies Roger Arndt, Hydrodynamics Expert speaking: “So, if you look at this. The first thing we see here is this very strong vortex here. So you have like a sledge hammer effect. Every time one of these one of these forms collapses BANG you have a sledge hammer.”