The LEA Inclusion Rating Scale

advertisement

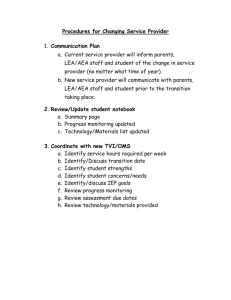

The LEA INCLUSION RATING SCALE: A tool for supporting self-review Dave Tweddle, Diane Risk, Professor Mel Ainscow, The University of Manchester, Andy Simpkins, Greater Merseyside SEN Regional Partnership, Diane Whalley, North West SEN Regional Partnership dave.tweddle@ukgateway.net diane.risk@talk21.com mel.ainscow@manchester.ac.uk. andy.simpkins@stockport.gov.uk diane.whalley@btconnect.com Introduction During the past three years, the Greater Merseyside and North West Special Educational Needs (SEN) Regional Partnerships have worked with The University of Manchester on a range of issues relating to the promotion of inclusive policies and practices. A key component of this initiative has involved working with Local Education Authorities (LEAs) in the two regions on the development of a review instrument called The LEA Inclusion Rating Scale. We need to be clear about what we mean by the term ‘the LEA’. It is understood, of course, that the maintained schools in a local authority are part of ‘the LEA’. Within this context, however, we are taking the ‘the LEA’ to mean the people, services and units that comprise the Council’s Education Department. It is important to stress that this is not a manual that provides standardised instructions for using the Rating Scale. Indeed, there is no single correct way of using the instrument. It was intended to be a flexible tool that can be used in a variety of ways to support the self-review process. It can help the LEA to orchestrate a process that: engages stakeholders; raises awareness; identifies issues for further investigation; and, eventually, clarifies priorities for development. However, the detail of precisely how it is used is a matter for each LEA to decide and should be influenced by the unique circumstances and context of that LEA. The Rating Scale materials, and the way in which they have been used in LEAs, have evolved during this development period. They have not been copyrighted or produced commercially, and have been made freely available on request with permission to copy or modify in whatever way seems helpful. This short pamphlet, therefore, describes ‘work in progress’. It contains the text of the materials currently being used, and provides an account of their development and some possible applications. Early Work This work began in 2001 when the Greater Merseyside SEN Regional Partnership commissioned the University of Manchester to work with representatives of the six Merseyside LEAs on ‘the promotion of inclusion’. A consensus quickly emerged that the first step ought to be to clarify what is meant by ‘inclusion’. Although the term has been in popular use for some years, there was a degree of confusion about its precise meaning – certainly between, and often even within, individual LEAs. Reaching agreement on a working definition of inclusion was not as difficult as some colleagues felt that it might be, and the following key ideas quickly emerged. It was agreed that inclusion is concerned with the ‘presence, participation and achievement of all learners’. ‘Presence’ is taken to be about where children and young people are educated, and whether they attend regularly and arrive punctually. ‘Participation’ is concerned with the quality of learners’ educational experiences, their self-esteem, whether they feel valued and that they belong, and the quality of services received by their parents or carers. And, ‘achievement’ (as opposed to ‘attainment’) is about learning outcomes across the whole curriculum, both inside and outside the classroom. It was further agreed that our aspiration should be to promote inclusion for all children and young people. Nevertheless, it was assumed that an emphasis should be placed on those groups of learners who – for whatever reason – may be at risk of marginalisation, underachievement or exclusion. Safeguarding the interests of our most vulnerable learners, it was argued, is a fundamental responsibility of the LEA. It should be noted therefore that, from a very early stage, this work was not characterised as a SEN initiative. Finally, it was also recognised that the development of inclusive policies and practices is a complex and continuous social process. It is concerned with engaging a wide range of stakeholders in identifying and removing barriers to the inclusion of all learners. In other 2 words, the promotion of inclusive education needs to be seen as a long-term strategic aspiration. Agreeing a working definition of inclusion was felt to be a prerequisite to effective collaboration between the LEAs in the Greater Merseyside region. It was regarded as an essential first step, providing a basis for the development of procedures for reviewing inclusive practice, recognising and celebrating good practice, and identifying issues for further development. Such a definition was eventually agreed that was based on the ideas described in the previous paragraphs. This was called the ‘Greater Merseyside Position Statement on Inclusion’. The Statement, which appears in full below, was formally endorsed by the Greater Merseyside Chief Education Officers’ Group and became the touchstone for all subsequent developments. GREATER MERSEYSIDE POSITION STATEMENT ON INCLUSIVE EDUCATION Greater Merseyside LEAs are committed to working with each other, and with all other relevant stakeholder groups, in order to promote inclusive education across the region. This commitment is underpinned by the following shared understanding of the meaning of inclusion. Promoting inclusive education involves identifying and removing barriers to the ‘presence, participation and achievement’ of all children, young people and adults. We believe that this commitment embraces a fundamental responsibility to place a particular emphasis on those learners who may be at risk of underachievement, marginalisation or exclusion. ‘Presence’ is concerned with where learners are educated, and whether they attend regularly and arrive punctually. In line with Government policy, we believe that wherever possible learners should be enabled to receive their education in a mainstream setting. ‘Participation’ is concerned with the quality of learners’ educational experiences, whether they feel involved and valued, and the quality of services received by their carers/parents. We believe therefore that learners’ own views and opinions, and those of their parents/carers, should form an essential part of any judgements made about the quality of their participation. ‘Achievement’ is concerned with learning outcomes across the whole curriculum, both inside and outside the classroom. We believe, therefore, that achievement should not be judged solely on the basis of test and examination results. It is acknowledged that the development of inclusive policies and practices is a complex and long-term social process. It is a process that needs to engage actively all of those involved in the education of children, young people and adults. In particular, it is recognised that promoting inclusion should be an aspiration for the ‘whole LEA’ with all individuals, services and units within the organisation understanding the contribution that they make. Finally, the Greater Merseyside LEAs are committed to evaluating progress towards more inclusive policies and practices. We believe that such progress should be judged in terms of the impact of our policies and practices on the presence, participation and achievement of all learners. 3 Towards a Review Framework During the development of this Position Statement, it became clear that the promotion of inclusion needs to be tackled on a ‘whole-LEA’ basis. In other words, everything that the LEA does may facilitate or inhibit the development of more inclusive policies and practices. Every service and unit within the LEA has a contribution to make. This was an important idea. Everybody in the LEA needs to understand what inclusion is, ‘own’ this shared aspiration to promote inclusion, and work out how they can make a contribution. This applies to the senior leadership team, finance officers, those responsible for governor training, school improvement officers, personnel officers, educational psychologists, pupil welfare officers and so on. This, of course, cannot be achieved by groups of professionals working in isolation. It requires genuine collaboration across the whole LEA. The next step, therefore, was to agree the factors, or aspects of the LEA’s operations, that might potentially facilitate or inhibit progress towards more inclusive policies and practices. Twelve factors were identified. These were: Definition Leadership Attitudes Policies, Planning and Processes Structures, Roles and Responsibilities Resourcing Support and Challenge to Schools Responding to Diversity Specialist Provision Partnerships Use of Evidence Staff Development and Training By this stage, therefore, agreement had been reached on the nature of inclusion itself and there was a consensus around the idea that the promotion of inclusion needed to involve the whole LEA. More specifically, the totality of the LEA’s operations had been broken down into twelve factors that could be used as a starting point for evaluating how effectively the LEA as a whole is tackling the issue. The LEA Inclusion Rating Scale The next step involved taking each of the factors in turn and deciding what a LEA ‘performing well’ would ‘look like’. In other words, a set of descriptors was developed for each factor against which the performance of the LEA could be judged. A limit of two or three short sentences per factor, containing a total of no more than 60 to 70 words, was imposed. This discipline was intended to ensure that only key ideas were included and that the instrument did not become unwieldy or cumbersome. Such a set of descriptors was agreed for each of the twelve factors. The factors, and their associated descriptors, constitute The LEA Inclusion Rating Scale that appears in full on the next two pages. 4 THE LEA INCLUSION RATING SCALE Definition In a LEA performing well, there is a short and clear definition of ‘inclusion’. It is understood and supported across all services and units within the organisation, and by headteachers and others who work in schools. Other key stakeholders outside the LEA, particularly Health and Social Services, understand and support the LEA’s policy aspirations in terms of promoting inclusive education. Leadership In a LEA performing well, senior managers provide clear leadership on inclusion issues. They articulate consistent policy aspirations for the development of inclusive practice. They acknowledge and celebrate inclusive practice, and they challenge unacceptable practice. Attitudes A LEA performing well is a positive, ‘can-do’ organisation. Equity and social justice are two key values. There is a commitment to identifying and removing barriers to the promotion of inclusion, and the provision of high quality services for ‘at risk’ groups of learners is a high priority. Policies, Planning and Processes In a LEA performing well, the promotion of inclusive education is strongly featured in important policy documents. The LEA’s definition of, and commitment to, ‘inclusion’ permeates planning processes and is reflected in the Education Development Plan and other LEA plans. Structures, Roles and Responsibilities In a LEA performing well, services and units have a clear role in terms of promoting inclusive policies and practices. They work effectively together, providing a coherent and co-ordinated service to schools and parents/carers. The management structure of the LEA facilitates co-ordination on inclusion issues. Resourcing In a LEA performing well, the level of resources available to support inclusion are comparable to other similar LEAs. The mechanisms used to distribute available resources, both human and financial, are designed to support inclusion and effectively target groups of learners that are at risk. Funding mechanisms are designed to empower individual schools, and groups of schools, to work flexibly and creatively in order to identify and overcome barriers to inclusion. 5 THE LEA INCLUSION RATING SCALE Support and Challenge to Schools In a LEA performing well, schools receive consistent and effective support and challenge on inclusion issues. Headteachers understand the criteria that are used to judge how inclusive schools are. Inclusive practice is recognised and celebrated, and ‘counterinclusive’ practice is challenged. The LEA facilitates arrangements that enable schools to provide support and challenge to each other on inclusion issues. Responding to Diversity A LEA performing well facilitates the development of additional programmes and curriculum initiatives in schools that are designed to improve the presence, participation and achievement of all pupils. The LEA encourages schools to place a particular emphasis on meeting the needs of those learners most at risk of marginalisation, underachievement and exclusion. Specialist Provision In a LEA performing well, there is a clear strategy for reducing the number of children and young people being educated outside mainstream settings. There is a clear role for specialist provision, including special schools, for promoting inclusive education and building capacity in mainstream schools. Special schools ensure that their pupils have access to appropriate mainstream experiences. Partnerships In a LEA performing well, there is a strong partnership with schools that is characterised by a shared commitment to policy aspirations on inclusion. There is effective cooperation between the LEA, Health and other Council Departments on inclusion. There is an effective partnership between the LEA and the voluntary and independent sectors on inclusion. Use of Evidence In a LEA performing well, there are clear success criteria that are linked to a definition of inclusion. Individual schools and the LEA collect evidence systematically that is linked to this definition. This evidence is both quantitative and qualitative, and incorporates the views and opinions of learners and their parents/carers. Staff Development and Training A LEA performing well has a properly funded staff development strategy that recognises the importance of continuing professional development. The LEA ensures that all members of staff are provided with appropriate awareness-raising and role-specific training opportunities on inclusion issues. 6 We next attached a simple, four-point rating scale to the instrument so that the LEA’s performance could be judged against the descriptors where: 1 means: 2 means: 3 means: 4 means: NR means: The LEA is performing well. There are several significant strengths, and no obvious weaknesses. The LEA is performing quite well. On balance, strengths outweigh weaknesses. The LEA is not performing very well. On balance, weaknesses outweigh strengths. The LEA is performing badly. There are no obvious strengths and several significant weaknesses. No response. You have insufficient information to make a judgement. The LEA Inclusion Rating Scale Definition 1 2 3 4 NR Leadership 1 2 3 4 NR Attitudes 1 2 3 4 NR Policies, Planning & Processes 1 2 3 4 NR Structures, Roles & Responsibilities 1 2 3 4 NR Resourcing 1 2 3 4 NR Support & Challenge to Schools 1 2 3 4 NR Responding to Diversity 1 2 3 4 NR Specialist Provision 1 2 3 4 NR Partnerships 1 2 3 4 NR Use of Evidence 1 2 3 4 NR Staff Development & Training 1 2 3 4 NR We understand that the Rating Scale is often difficult to complete. There are at least two reasons for this. First, a single numerical rating must be allocated to each factor that might be described by two or three different statements. The task, which is often difficult, is to weigh the evidence and reach a ‘balanced judgement’ for each factor. Secondly, there is no ‘middle’ rating as, for example, a 3 would be in a 5-point scale. If a LEA is not thought to be performing ‘well’ or ‘badly’, respondents need to decide whether strengths outweigh weaknesses (2) or weaknesses outweigh strengths (3). We believe that these design features combine to generate lively discussion, engage participants fully in the process, and consequently develop a deeper understanding of the issues. 7 Using the LEA Inclusion Rating Scale It has been emphasised previously that there is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way of using the Rating Scale. Its purpose is to support the self-review process, and the detail of how it is used should be decided by each individual LEA to take account of its own context and circumstances. This section, therefore, does not provide step-by-step instructions. However, it may be useful to describe some of the lessons that we believe have been learnt, and to identify some of the key decisions that need to be made in planning the process. First of all, we have never sent out the Rating Scale, by post or electronically, and asked stakeholders to return it completed. This has always seemed to us to undermine the function of engaging stakeholder groups in the debate and raising awareness of the issues. We have always used the Rating Scale at seminars or conferences that have been specifically designed to provide opportunities for discussion and generate the most reliable data. All LEAs that have used the Rating Scale have held at least two such conferences, one for LEA staff and one for headteachers. Some have held a third conference for other stakeholder groups such as governors, elected members, the voluntary sector, colleagues from Social Services and Health, and so on. These conferences have usually lasted for two to two and a half hours, and have tended to follow a broadly similar format. All headteachers have usually been invited to the headteachers’ conference. We have found cabaret seating to work best. This enables inputs to be made ‘from the front’, and colleagues to work in small groups, without time being wasted moving to and from breakout rooms. The hour before coffee usually begins with a brief explanation of the process, the assumptions that underpin it, and the materials that are to be used. For the remainder of this first session, delegates are asked to record their own rating for each of the twelve factors as each factor is described in turn. This activity is completed independently – no conferring! Following coffee, colleagues are asked to share their ratings with others sitting at the same table. It is suggested that they focus mainly on those factors that have attracted diverse ratings in order to explore the reasons why this might be so. During this hour, colleagues are told that they can change their ratings in the light of this discussion if they wish, but there is no pressure to reach a consensus. Feedback from delegates on this activity is always very positive. At the end of the conference, delegates hand in their completed Rating Scale. Attendance at the conference for LEA staff raises more difficult issues. We are clear that the whole LEA needs to be represented – especially those parts of the organisation that may think that inclusion has little to do with them! However, difficult decisions need to be made concerning the ‘seniority’ of those representing each service or unit, bearing in mind the need to be inclusive but also the nature of the activities to be undertaken. We have found that this process works well with headteachers and LEA staff who tend to have clear views about the LEA’s performance on all, or certainly most, of the twelve factors. This tends not to be the case with colleagues from other stakeholder groups, who often have strongly held views about particular factors, but no view at all about others. A range of alternative strategies have therefore been used which are based loosely on the Rating Scale but allow delegates to focus primarily on those issues most relevant to them. We have often used flipcharts to record in summary the views of delegates. There is an issue regarding who facilitates this process. Obviously, LEAs are free to design and manage their own process although none in the Greater Merseyside or North West regions, to our knowledge, have done so. We have also discussed the idea of peersupported self-review, or LEAs providing this service for each other, although to our knowledge this has not yet happened either. Instead, all of those LEAs that have used the Rating Scale to date have used facilitators from the University of Manchester. 8 Collecting Additional Qualitative Data It was suggested earlier that the process outlined in the previous paragraphs enables a profile to be generated that describes the perceptions of different stakeholder groups across all twelve factors in the instrument. However, additional qualitative data is needed to understand why some factors are rated highly and others not so. At the close of the conferences, therefore, these limitations are spelt out to delegates. It is explained that the Rating Scale data enables us merely to identify the issues that need further investigation. Delegates are therefore invited to provide their name and a contact telephone number. A sample of delegates is then contacted by telephone by those who facilitated the conference during the week or so following the conference. These telephone interviews are structured around specific questions that have been generated by an analysis of the Rating Scale returns. In our experience, the overwhelming majority of delegates are willing to have such a discussion that usually lasts no more twenty to twenty-five minutes. We believe that this procedure, designed to develop a deeper understanding of the perceptions of stakeholders, is extremely important. It enables the facilitators to feed back to the LEA not just what stakeholders think about the performance of the LEA, but also why they hold the views that they do. However, undertaking a large number of telephone interviews is a labour-intensive, and ultimately expensive, procedure. We are therefore currently experimenting with alternative methodologies. One of these, for example, involves asking each table to nominate a representative to attend a follow-up meeting with the facilitators a week or so after the conference. The purpose of this follow-up meeting is to discuss the issues generated by an analysis of the Rating Scale returns. In summary, we are clear that the Rating Scale does its job in terms of identifying the key issues. However, we also know that additional qualitative data is needed to make better sense of the aggregated ratings. Individual interviews provide a rich seam of data, but it is a costly exercise. In the coming months, we will continue to experiment with alternative, less expensive processes designed to achieve the same outcome. The Notion of ‘Levers’ The role of the external facilitators, who manage this process on behalf of the LEA, comes to an end with the delivery of a report that sets out the quantitative and qualitative data that have been collected, and provides an analysis of the issues raised by stakeholders. Obviously, the responsibility for assimilating these findings into existing review and planning processes, and deciding how best to proceed, rests with the individual LEA. However, within the context of this exercise, we have found the idea of ‘levers’ to be a useful one. Levers can be thought of as a ratio of the impact of an activity relative to the financial and human cost of the activity. So, a ‘high leverage’ activity will have a significant impact on practice for a modest investment of time and energy. And conversely, a ‘low leverage’ activity will be costly without achieving a great deal. The data collected by using the Rating Scale often reveal several issues that it may be useful for the LEA to address. The notion of levers can be useful in deciding priorities for action. In other words, in the light of evidence that has been collected, what can the LEA do that will move the inclusion agenda forward most significantly for the least investment of time and energy? We firmly believe that the idea of levers is useful in terms of informing a discussion within the LEA about how to respond to the data generated by the Rating Scale. We are also beginning to develop an understanding of the leverage that may be associated with the twelve factors described in the Scale. However, this is an aspect of this work which is ongoing and which, hopefully, will be the subject of a further publication at some stage in the future. What the Rating Scale Can and Cannot Do It may be helpful at this point to summarise our experience of using the Rating Scale in terms of what we believe it can do and, of equal importance, what it cannot do. The Rating Scale was designed as a tool for supporting the self-review process. In general terms, we have 9 found that the instrument is successful in terms of what it was intended to do. It is quick and easy to use. It can be used with a range of stakeholder groups. It is flexible; that is, it can be used in a variety of ways and in different contexts. Importantly, the data is easily collated and can be used to generate a quantitative profile of the ratings of each stakeholder group across all twelve factors in the Scale. In this way, the review process identifies issues that need to be addressed by the LEA as well as the strengths of existing practice. We strongly believe that one of the major benefits of this work relates to the review process itself, as opposed to the aggregated ratings that are generated by the process. In other words, the Rating Scale has consistently acted as a potent catalyst for generating a debate, within the LEA and with headteachers and other stakeholders, about the nature of inclusion and the roles and responsibilities of all those who have a contribution to make. It is important to be clear that the Rating Scale collects information about perceptions. Using the Scale with different stakeholder groups will only establish what those groups think about the LEA’s ‘leadership’, ‘use of evidence’ and so on. Nevertheless, perceptions are important and need to be dealt with. The use of the Rating Scale, for example, has occasionally resulted in the LEA communicating its policy differently, rather than changing its policy. It should be emphasised, too, that whilst data collected using the Rating Scale identifies the perceived strengths and weaknesses of the LEA’s approach to promoting inclusion, it will not indicate why. ‘Support and challenge to schools’ or ‘leadership’, for example, may receive consistently poor ratings. However, collecting additional qualitative data is essential in order to develop a deeper understanding of the underlying issues. Finally, the Rating Scale is ‘schools-dominated’. It was not designed to be a ‘Local Authority Inclusion Rating Scale’. As a result, Education Departments that are already integrated with Leisure Services, or aspects of Social Care, need to think very carefully before using the instrument in its present form. However, the Rating Scale has been used by LEAs as part of their preparations for responding to Every Child Matters. Future Developments During 2004-2005, we are hoping to make progress on a number of key issues regarding the further development of this work. By Easter 2005, seven or eight LEAs in the Greater Merseyside and North West regions will have undertaken a review of current practice using the LEA Inclusion Rating Scale. To date, officers from those LEAs have not shared with each other their impressions of the process, and there has been no formal follow up to find out what, if anything, has changed as a result of each review. During the spring term 2005, therefore, it is intended to hold one or more seminars for senior officers representing those seven or eight LEAs at which the following questions will be addressed: How can the Rating Scale, and the way in which it is currently used, be improved? Which factors are most commonly identified as barriers to progress? And what has been learnt about overcoming those barriers? More specifically, in responding to the outcomes of the review, what has been learnt about ‘levers’ in the change process? During the summer term 2005, it is planned to hold a conference open to representatives from all LEAs in the North West and Greater Merseyside regions, the purpose of which will be disseminate the outcomes of this work to date. 10