Hi Membership Reps: - The College of New Jersey

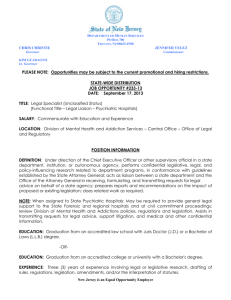

advertisement

Dear Membership Reps: There were articles in two New Jersey papers over the past few days about TCNJ’s proposed “transformative change” and each contained the same error relating to the number of hours that a new “enhanced” course would meet if this change to the curriculum takes place. Steve Briggs’ memo today, Jan 21, addresses this issue. However he did not mention any intention by The College to correct this serious error nor whether Jesse Rosenblum is going to insure that it is not repeated in any future articles which will be published. When being interviewed by Kelly Heyboer, the Star-Ledger reporter, on Friday, January 17, I was careful to explain that the new “enhanced” courses would meet for the same amount of time each week as the current courses. This means that less time will be spent by students ( and faculty ) in the classroom under this new system than is presently the situation. For many faculty, this is the primary appeal of the proposal although certainly not the only one. Kelly referred to these new courses as being “four credits” numerous times and I kept reminding her that this was not the case. The enhanced nature of the classes is supposed to compensate for the reduction in class time although exactly how that is to work has not yet been fully explained or defined. Evidently I wasn’t clear enough in making this point. Her statement in the article that “.....since the courses will be longer and more difficult, the amount of time an average professor spends in the classroom should not change.” is confusing and not consistent with that the earlier one that new classes will require “...an extra hour a week in the classroom.” The Trenton Times did include the statement that the classroom time should not change in its article leaving the clear impression that the new classes will meet for one hour longer per week than the present ones. Obviously having folks believe that the new classes will meet longers than the currect ones is better from a PR standpoint than having the public seize on the point that faculty and students will be spending fewer hours in the classroom to get a degree under this new system. Explaining all the subtle nuances of this complex issue would probably be too time consuming and involved for an article of this type. However I believe it is unfortunate this erroneous impression is out there and evidently not going to be corrected by The College. Naturally we all know that what appears in print after giving an interview is quite often a surprise but this goes a bit too far. Both the StarLedger and Trenton Times (AP) articles are reproduced below if you’d care to read everything. You can be sure that we will make certain that any agreement to implement a modification of this type will have a positive impact on the work load of faculty and not be a mere cosmetic change done for PR purposes. Ralph Edelbach =============================================================== The Star-Ledger Sunday, Jan 19, 2003 Key portion Under the new system: …….The college will phase out three-credit classes, which require students to spend three hours a week in class. Instead, all courses will be the equivalent of four-credit seminars, requiring an extra hour a week in the classroom, along with more writing and reading outside of class. Classes will remain small, with about 30 students or fewer in each course. Complete Star-Ledger Article Revolution in classwork is brewing in Ewing - College of New Jersey to scrap the lecture system Sunday, January 19, 2003 BY KELLY HEYBOER Star-Ledger Staff The College of New Jersey could become the first state college in the nation to abandon the traditional three-credit course system in favor of a more demanding curriculum used by such exclusive private colleges as Swarthmore, Vanderbilt and Amherst. Starting in the fall of 2004, the college’s incoming freshmen will take longer, more rigorous classes that require more reading, more time in the classroom and more one-on-one interaction with professors, according to a plan outlined by the college’s president last week. While the courses will be tougher, students will be required to enroll in fewer classes overall. The average undergraduate will take four courses a semester – instead of the traditional five – to graduate on time. R. Barbara Gitenstein, the college’s president, said the curriculum plan is a radical departure for a state school. When it is implemented, the College of New Jersey—already New Jersey’s most selective public college—will operate less like Rutgers or Montclair State university and more like a private liberal arts school. Some professors already have balked at the idea, and Gitenstein expects other state colleges will be watching to see whether the 6,800-student College of New Jersey, located in Ewing in Mercer County, can pull off the unprecedented curriculum change. “I’m anticipating there being skepticism,” Gitenstein said. But she added: “There is no indication that this is not going to work. ... I think the difference is other public institutions have not been courageous enough to do it.” Under the new system: The college will phase out three-credit classes, which require students to spend three hours a week in class. Instead, all courses will be the equivalent of four-credit seminars, requiring an extra hour a week in the classroom, along with more writing and reading outside of class. Classes will remain small, with about 30 students or fewer in each course. Students will take fewer courses to graduate. Under the current system, students must take five classes a semester—40 courses over four years—to earn a bachelor’s degree. Under the new system, students will need 32 to 34 classes to graduate, meaning they will average four courses a semester. All of the college’s courses will be redesigned to replace traditional lectures with class discussions and team projects. Students will be expected to complete extensive readings before they come to class, so professors can focus on leading discussions about concepts instead of lecturing about facts. Professors will teach fewer courses. Instead of a maximum of four courses a semester, the average professor will teach no more than three classes. However, since the courses will be longer and more difficult, the amount of time an average professor spends in the classroom should not change. Professors will be expected to invite students to work with them on faculty research projects outside of class. Current students and those who enroll before the fall of 2004 will be exempt from the new requirements, though they may enroll in some of the redesigned courses as the courses are rolled out over the next few years. Stephen Briggs, the college’s provost, said the new system should produce better graduates who are more thoroughly prepared for graduate school and the work world. Education studies show students get more out of college when they are challenged and take an active role in their courses. “We are going to expect you to do a lot of preparation before you come into class, more reading ... more writing, more group projects,” Briggs said. “The faculty role is to probe what you know.” BATTLE LINES The college will offer some pilot courses this semester to test the new teaching method. Clear battle lines, however, have been drawn in some corners of the school. Some professors and departments—including the entire physics department—are fighting the changes. Physics department chairman Paul Hiack, who has been at the school for more than 40 years, said the college’s physics courses cannot become any more intense without becoming too difficult to pass. So the new curriculum system will only end up cutting the number of courses students take and reduce the breadth of graduates’ knowledge, Hiack said. “I think that’s wrong. I’m a firm believer in the old saw, ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,’” Hiack said. “I don’t think you need an enormous, wholesale change like this.” Though there has been some criticism, most of the college’s 350 full-time faculty members are excited about shaking up the system, said Dan Crofts, president of the faculty senate and chairman of the history department. “There are pockets of discontent in the faculty. But I think it’s moving ahead—and it’s especially strongly supported by the junior faculty,” Crofts said. “Any institutional change causes pain. But this place has as strong a commitment to change as anywhere.” Founded in 1855 as the New Jersey State Normal School, the college began as a teacher training school and gradually expanded to other fields of study. In the 1970s, the college, by then called Trenton State, decided to limit its size and focus on undergraduate liberal arts education. By the late 1990s, the college—renamed the College of New Jersey in 1996 -- was rising in national rankings and developing a reputation as a school that offered a private school atmosphere at public school prices. The average in-state undergraduate living on campus currently pays $14,859 annually for tuition, room, board and fees. As a result, the college saw the quality of its freshman class rise every year. The average SAT score of this year’s regularly admitted incoming class was 1,295, the highest among New Jersey’s public colleges. The college spent about $15,000 over the last three years on consultants and outside experts to help consider the new curriculum, school officials said. The college expects the new curriculum will eventually cost the same or less than under the current system. The reduction in the number of required classes should shrink the number of adjunct professors the college needs to hire each semester. ACCREDITATION ISSUE Many questions are unanswered, however, including how the college will deal with transfer students who enroll with credits from county colleges and other schools that use the traditional three-credit course system. Several departments—including engineering, nursing and education—have questioned how reducing the number of required classes will affect their accreditation and licensing requirements, said Ralph Edelbach, an associate professor in the technological studies department and president of the local faculty union. “There are a lot of pieces yet that really have to be defined better. It’s still rather nebulous in spots,” Edelbach said. “Classes are to be more ‘intensive.’ But what exactly does that mean?” Gitenstein, the college’s president, believes all the kinks will be worked out eventually and the College of New Jersey will serve as a model around the nation for public schools that are ready to make a similar change. “I hope so,” Gitenstein said. “I really believe this is something good for students.” Kelly Heyboer covers higher education. She may be reached at they boer@starledger.com or (973) 392-5929. ==================================================================== The Trenton Times – Monday, Jan 20, 2003 ( AP ) Key Portion – Under the new system, the average undergraduate would take four courses a semester, instead of the traditional five, to graduate on time. The college plans to phase out three-credit classes, which require students to spend three hours a week in class. Instead, all courses will be the equivalent of four-credit seminars, requiring an extra hour a week in the classroom, along with more writing and reading outside of class. Complete Trenton Times Article TCNJ may abandon three-credit system EWING (AP) _ The College of New Jersey plans to replace the traditional three-credit course system with a more rigorous curriculum favored by private colleges, the school has announced. If the New Jersey college makes the switch in the fall of 2004, it would become the first state college in the nation to do so. College President R. Barbara Gitenstein said courses will be tougher, involving more reading and time spent in class, but students will take fewer classes at a time. Stephen Briggs, the college’s provost, said the new system should produce graduates who are better prepared for graduate work and careers. Some professors and departments including the entire physics department are opposed to the change. Physics department chairman Paul Hiack said the college’s physics courses cannot become any more intense without becoming too difficult to pass. He claims the new curriculum system would cut the number of courses students take and therefore reduce the breadth of graduates’ knowledge. “I’m a firm believer in the old saw, ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,’ “ Hiack told The Star-Ledger of Newark. Under the new system, the average undergraduate would take four courses a semester, instead of the traditional five, to graduate on time. The college plans to phase out three-credit classes, which require students to spend three hours a week in class. Instead, all courses will be the equivalent of four-credit seminars, requiring an extra hour a week in the classroom, along with more writing and reading outside of class. All of the college’s courses will be redesigned to replace traditional lectures with class discussions and team projects, Gitenstein said. The College of New Jersey is the state’s most selective public college. The average SAT score of this year’s regularly admitted incoming class was 1,295. The college expects the new curriculum will cost the same or less than under the current system. The reduction in the number of required classes should shrink the number of adjunct professors the college needs to hire each semester, officials said. ====================================================== Briggs’ Memo - Jan 21, 2002 10:31 a.m. In recent days, the President and I have introduced TCNJ’s plan for “academic transformation” to the news media in New Jersey. As you might expect, it is difficult to convey a complicated curricular story of this sort to a general reading audience, so we are delighted with the media’s interest in our efforts to enhance the educational experience of our students. In addition to the article in Sunday’s Star Ledger (which was picked up by the AP wire), Jesse Rosenblum expects additional articles in the Trenton Times, the Trentonian, and the Philadelphia Inquirer. In our presentations, we have attempted to communicate clearly and carefully the recommendations contained in the CAP documents from May and December 2002. Even so, some of the distinctions that are important to us—e.g., increased expectations outside of class without increased contact hours per week—are easily confused in translation. When in doubt, refer to the documents of record from CAP and CFA (posted on the academic affairs website), which will be the subject of discussion in coming weeks. email/tc-2.doc )