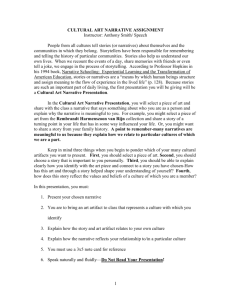

The State of Narrative in Computational Settings

advertisement

The State of Narrative in Computational Settings - How can the multi linear digital literature be read?1 By Rasmus Blok, University of Aarhus, Denmark New digital forms Digital technology has become parts of our common life, as readers, writers, teachers, students, librarians and publishers. Literary studies and their underlying concepts as we know them are therefore faced with far-reaching changes. Fundamental questions, such as “What is an author?”, ”What is a text?”, "What is a story?" and “What is a reader?” must be asked again with fresh demand and answered in various new ways in light of the presence of a new technology. Especially relevant to the practice of contemporary fiction and culture are the changes the narrative is undergoing. Since Aristotle it has been a generally accepted narrative norm that stories are built around “a beginning, a middle, and an end” (Aristotle: Poetics, The Loeb Classical Library, 1995, p. 55). This is a schema that in many ways regardless of theoretical angle or literary form has been kept unchanged. But what happens when we are dealing with a computer based text? Can the Aristotelian view also account for the digital narrative? My concern here is digital narratives within the frame of digital literature. Until now there has been no general or fulfilling attempt to define digital literature. Digital literature is among others also known as hyperfictions, interactive fictions or hypertext novels. I define digital literature as being a digitally and computer based literary work of art, sometimes containing graphics and sounds, and which is designed and based on a link-structure. The literary digital work of art therefore contains interactivity along with the narration and is therefore situated between, but does not include, full digital reproduction of printed literature on the one side and the computer gamegenre on the other. Digitally reproduced literature, fx Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet put on the Internet, contains a narrative but no interaction and computer games fx like Doom or Hitman, contains interactivity but no ‘proper’ narratives in a novelistic sense, since it only employs narrative elements as a context for the game. The greater or lesser element of interactivity in these digital narratives – the reader’s choice between different links, that can either be graphically or textually based – institute a norm that does not presume a single designed path through the fiction. The reader are given a series of choices and the narrative does therefore not exist as a locked set of sequences, but is more to be seen as a This paper is based on a longer forthcoming article (Rasmus Blok: "I try to recall..." in Huang, Simonsen & Thomsen (ed.): Reinventions of the Novel. History and Aesthetics of a Protean Genre, Rodopi, Amsterdam, 2004). 1 1 network, that has to be exploited by the reader. The lack of a sequential order can therefore theoretically cause narratives with no predetermined beginning, middle or end, as assumed in narrative theory. Can these stories then be accepted as narratives or must they be rejected as such? Hypertext as the historical background The digital narrative is shaped by the development of hypertext. Theodore Holm Nelson coined hypertext as a concept in the beginning of the sixties, but many years before in 1945, Vannevar Bush, had idealized it in his idea of the Memex2. In Nelson’s definition hypertext is characterized by “non-sequential writing – text that branches and allows choices to the reader, best read at an interactive screen. As popularly conceived, this is a series of text chunks connected by links which offer the reader different pathways” (Theodore Holm Nelson: Literary Machines, private publication, 1981, p. 0/2). The development of the hypertext, Theodore Nelson remarks, is what turned the computer into “literary machines”. The development of hypertext, and the spread of personal computers or “literary machines”, gave in the early 90’s cause for literary reflection by a small group of literary critics, who at that time where heavily influenced by deconstruction or poststructuralistic theories. Among the first literary critics to deal with hypertext and digital narratives were George P. Landow and Jay David Bolter, whom together initiates or at least popularizes what still is very much the dominating thought in the critical reception of digital literature and narratives in general. In his book Hypertext: The Convergense of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology Landow explains, already assumed by its subtitle, that there is a match between poststructuralistic literary theory and hypertext. Landow makes clear that these two ideas, which might seem unconnected, “have increasingly converged” (George P. Landow: Hypertext 2.0 – the Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997, p. 2). With this “convergence” Landow points towards what Roland Barthes describes as an ideal textuality, and assert that this “precisely matches that which in computing has come to be called hypertext” (Landow 1997:3). By this Landow finds a heavy argument as a literary critic to work with poststructuralism in relation to digital literature and hypertext, as: 2 In a crucial article Vannevar Bush proposed that science together with technology should develop new means for cataloguing, and that its ideal should simulate the human mind. Bush’s own suggestion was the so-called Memex that as a concept looks like the computer based hypertext of today (Vannevar Bush: “As we may think”, Atlantic Monthly 176 (July 1945), p. 101-108). 2 “… critical theory promises to theorize hypertext and hypertext promises to embody and thereby test aspects of theory, particularly those concerning textuality, narrative, and the role and function of reader and writer” (Landow 1997: 2). Whereas Landow seeks a theoretical foundation of hypertext, Jay David Bolter sees hypertext more in relation to the history of literature. Bolter places hypertext in the literary tradition of avant-garde and modernism, which according to him, all along have been fighting to destabilize the text. The tradition of experimental literature is read as the exhaustion of the book leading towards its final death and replacement by more sophisticated systems such as hypertext, which is seen to liberate the writer of the tight bondage of the book. Bolter therefore argues that these movements not only are seen “as explorations of the limits of the printed page but also as models for electronic writing” (Jay David Bolter: Writing Space – The Computer, Hypertext and the History of Writing, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1991, p.132). From this viewpoint Bolter argues that digital literature becomes “the inevitable next step” and “the take-off” of literature (Bolter, 1991:132). These two tendencies have had an enormous impact on the general understanding of digital narratives and on the scholarly work generated ever since, and have in my view seldom been seriously challenged. As a consequence of the uncritical acceptance of this “convergence” theory, most critical work on digital narratives show great problems dealing with the content or more concrete aspects of the digital narratives. Views accepting this so-called convergence, most often end up copying the formalistic poststructuralistic analyses, reproducing its known dogma of irony, fragmentation, play of forms and the reverted role of the reader and writer. Most work often just talk about the great potential of digital literature in a futuristic manner, referring not to actual digital literature, but to ideal or theoretical examples3. Additionally the convergence-theory itself raises a series of problems. Most seriously Bolter and Landows argumentations ends up in the somewhat problematic statement, that poststructuralists like Jacques Derrida and Roland Barthes had been describing hypertext and digital literature without knowing it, and that they together with writers of avant-garde, modernism and postmodernism are set out to destroy the book. What seems to be forgotten here is precisely the fact that fx. James Joyce or Sterne did not destroy the book, but indeed developed it, and that As examples of this take the anthologies Page to Screen – taking literacy into the electronic era from 1998, edited by Ilana Snyder or Hypermedia and Literary Studies from 1991, edited by Paul Delany and George P. Landow. These two books contain many interesting articles, but only a few of the 30 articles actually refer to works of art, and none of them use any digital literary work of art beyond reference. Moreover most of them uncritically refer to and make use of the “convergence”-theory. 3 3 poststructuralists like Derrida presented their critique in book-form. And likewise, that the work of these people could not have been realized, had it not been for the formal conditions of the book. The ‘content’ of a digital narrative and its relation to closure Just like any other art form the digital narratives does not only present formal aspects. We read literary work of art as a whole, a joining of form and content, which in a simple way is what constitute a work of art. Content may in this respect be a problematic term to use, since the content of an interactive narrative is very hard to demarcate. Contrary to the book the borders of digital literature are not that easy to visualize and determine. You might say that the narrative or the content is located on a computer, a disc or a cd-rom, but it is difficult to be more precise, as the narrative is coded in software that by way of hardware is presented on a screen. Also through the reading of such narratives it is hard to demarcate the content, since you do not necessarily read all the content or for that matter read the exact same story as others, due to the interactive element. Regardless of the problems of demarcating the content of digital literature, we know it is there because of the common but nevertheless crucial and essential recognition; “that someone has been there before us” (Michael Joyce: Of two minds, University of Michigan Press, 1995, p. 135). Somebody made it with a purpose, and hereby we can assert some kind of intention that reaches beyond the formal aspects, and in a more common way constitute it as a work of art. What more or less then, has been missing from the reflection on digital narratives until now is a focus on the narrative and the implications of the reading, exactly because the content is hard to demarcate and exactly because the reading in this case is no common affair. But instead most critics have just dismissed the narrative from the field of digital literature4. When focusing on the reading, we also realize that to read digital narratives is a battle to find an ending and thereby to conclude a meaning of the narration. The conventionally printed book refers to the past and is a reproduction of fictive events that have already taken place. It’s a linear narrative with a textual authority, where the reader is subjugated the authors choice all the way to the end. By the end the author is excluding what did not take place, and creates space for the “meaning” of the narrative. It is somewhat more problematic to get hold of the ending and defining the time of a digital narrative. First of all, because what happens is initiated by a present choice, but with the choices and structures preconfigured from the outset. 4 It is precisely because of these narrative problems and the mismatch with the Aristotelian view of narrative that Espen Aarseth dismisses the narrative from digital literature and thereby also avoids the necessary and essential discussion, by instead inventing a new term called ergodic, which then accounts for the ‘narrative’ elements in an otherwise narrationempty environment. 4 Narrative critics such as Peter Brooks and Frank Kermode, both use closure as the single entity that confers cohesion and significance on narratives in a way that strongly suggest that the experience of narrative closure numbers among the principle pleasures of reading. In Reading for the Plot Peter Brooks argues, using the sentence, as a paradigm for the narrative structure, that a narrative is not a whole without closure, just like a sentence is incomplete without its predicate. Peter Brooks states: “only the end can finally determine meaning” (Peter Brooks: Reading for the Plot, New York, Vintage, 1985, p. 22). It is this ending, or the anticipation of this ending that makes it possible for us to interpret the narrative, Brooks argues. For Frank Kermode it is the provision of an ending that makes a satisfying consonance with the origin and the middle possible and thereby provide a meaning (Frank Kermode: The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Narrative Fiction, Oxford University Press, 1966, 17). Kermode is arguing that the ending might not be physically provided by the text, as we as readers create our own sense of an ending, by making imaginative investments in possible patterns. What the ending does in this regard is to invalidate or validate our predictions of the outcome. What seem to be the key elements of endings are to make certain that the reader can have no further expectations to the narrative or what Barbara Hernstein-Smith define as closure: it simply removes any “residual expectations” concerning the narrative (Barbara Hernstein-Smith: Poetic Closure, Chicago University Press, Chicago, 1987, p. 30). There are physically nothing left to alter the story so the reader is free to make whatever she can get out of it. Having briefly mapped some of the nature and poetics of closure and endings, the problems concerning digital narratives should now be obvious. Reading digital narratives you encounter large numbers of narrative segments and often with an even larger number of links between them. This might render it difficult for the reader to exhaust the narrative and its possibilities, i.e. find the ending that removes any “residual expectations”. What then makes a reading end? Must the reader supply her own sense of an ending, as some critics suggest5? The strategies behind the digital narratives do not seem to correspond to the strategies of the printed book, and is not yet clearly crystallized in concrete genres. This has to do with the digital narratives still being in its infancy and not subsumed a single clear poetic or set of conventions. Where both writer and reader over the years have come to agree to the same conventions and genres of the printed book, this has not yet been the case for the digital narratives. Some seem to work like a puzzle, where the reader should put the pieces together, others work like conceptual art, where the Jane Y. Douglas fx. suggests this in her reading of Michael Joyce’s Afternoon, a story (Jane Yellowlees Douglas: “How Do I Stop this Thing” in George Landow (ed.): Hyper/Text/Theory, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994, p. 161). 5 5 job of the reader is to receive a main point, and yet others work like a collage of parallel and interconnected stories forming a greater picture. In this respect we may also have to alter our conception of reading or at least point to the differences when there is a shift in media. When dealing with digital narratives we often anticipate several readings because of the interactive element, whereas in the printed text we only do one in order to exhaust the narrative. We tend to have accumulative readings in the digital narratives, as we in the course of our several readings often encounter previously read narrative segments together with new ones. Also there are no clear divisions in a digital narrative such as the printed books chapters and page numbers. Besides the difficulty of ending and closure it is therefore also much harder to get an overview of the narrative, such as the length, the structure, the content and the content not yet read. The medium as part of the narration Together with the awareness of the narrative conditions in digital literature and the problems involving the content and the reading, it is clear that digital narrative is very much bound to its medium. The design and the functionality of digital narratives is openly tied to the technology that produce it, and the computer must therefore be brought into the discussion of digital narratives – as an meaning producing element that affects the narrative. This binding to a medium is also true of other narratives including those who still get printed in books. Seen in retrospect the media binding should have been obvious, but more than five hundred years with the printing press have made the conventions of the book transparent to us. The medium has slipped out of its adequate significance. Whereas from the outset many think that the digital narratives offers a greater freedom in the exercise of reading than the book, physically because of it’s interactive element and theoretically because of the “convergence”-theory, it very quickly shows itself often not to be the case. In spite of the digressiveness of the digital narratives and the possibility of choice, the choices is often tied to previously made choices, and former read passages can seldom be read again. In the digital narrative you do not have the same overview as is given to you with the book. You cannot skip pages, reread them or choose to read the end from the beginning at your own will. The reader of digital narratives has then often got a restricted perspective that complicates the reading and the forwardness of the narrative. Where the “convergence”-theory in regard of digital literature has repeated the conversion of the reader/writer-relationship from the poststructuralistic theory, i.e. the reader becomes his own writer of the digital narrative because of the interactive element, it is clear that this is not the case, when we read and focus on the media specific features of 6 the digital narrative. The truth is that in digital narratives the distance between reader and writer most often is kept and sometimes seems even larger than before. What furthermore becomes apparent is the element of non-trivial reading effort, that separates the narratives of the two media, and what the Norwegian critic, Espen Aarseth, has termed ergodic. Ergodic is coined of the two Greek words ergon and hodos, which signify “work” and “path” (Espen Aarseth: Cybertext, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997, p. 1). Whereas the reader of a conventionally narrative only has to do trivial work, i.e. move the eyes, turn the pages etc., the reader of a digital narrative must submit non-trivial work in the sense that she must make choices; choose links and different path in the narrative. By way of the possible interaction the digital narrative becomes a cybernetic text, or a cybertext, which indicates a text seen as a mechanical device as opposed to a metaphorical device for “production and consumption of verbal signs” (Aarseth 1997:21). The digital narrative is a textual machine, where the reader is part of that machine – the necessary piece in order to produce the narration. If, as a reader, you do not want to remain a chip in the “cybertext” and thereby only produce meaning, you have to be able to position yourself at a level of interpretation. As readers we must additionally be able to get a general view or a sense of the flowchart, of how the cybernetic text is configured, how it works, how the text is demarcated, how it is structured and how we as readers is part of the output of meaning. In this sense we have to become what Aarseth has labeled a meta-reader, which implies that we contribute to the production of meaning and at the same time reads its structure and functionality (Aarseth 1997:93). In a broader culturally perspective, digital literature has shown us what we already knew, but had forgotten in the long regime of the printed text – that the narrative is tied to a medium that have crucial and decisive impact on such relations as reader, narrative, author and work of art. This binding it shows also bears consequences for how the reading is carried out and in a broader perspective for what is read. Just look at the Internet for additional evidence: Here reading and writing is easily replaced with surf and chat. Cited literature Aarseth, Espen, Cybertext, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1997. Aristotele, Poetics, The Loeb Classical Library (trans. Stephen Halliwell), Cambridge 1955. Bolter, Jay David, Writing Space: The Computer, Hypertext and the History of Writing, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1991. Brooks, Peter, Reading for the Plot, Vintage, 1985. Bush, Vannevar, “As we may think”, Atlantic Monthly, 176 (July 1945). 7 Douglas, Jane Yellowlees, “How Do I Stop this Thing” in George Landow (ed.): Hyper/Text/Theory, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994. Hernstein-Smith, Barbara, Poetic Closure, Chicago University Press, 1987. Joyce, Michael, Of two minds, University of Michigan Press, 1995. Kermode, Frank, The Sense of an Ending: Studies in the Theory of Narrtive Fiction, Oxford Universsity Press, 1966. Landow, George P., Hypertext 2.0: The Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. Nelson, Theodore Holm, Literary Machines, self-published, 1981. 8