evidence from Russian and Lithuanian

advertisement

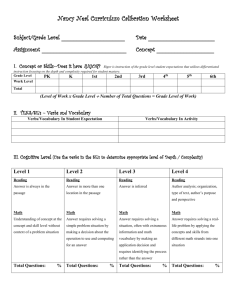

Case alternation and event structure: Evidence from Russian and Lithuanian Cori Anderson Princeton University Russian and Lithuanian share two usages of instrumental case: instrumental with verbs of moving body parts, as in (1a) and (2a), and with verbs of making sound, as in (1c) and (2c). Lithuanian, unlike Russian, allows accusative with such predicates as well (Ambrazas 2007), with a subtle difference in meaning: the accusative indicates the object (body part, source of sound) is an affected patient rather than a means for performing the action. For verbs of making sound, it is also important to note that these predicates can function intransitively, with the source of the sound as the sole argument, shown in (1d) and (2d). Unlike unaccusative predicates that have transitive counterparts, the addition of an external argument does not result in accusative case on the internal argument. Verbs of moving body parts do not license instrumental by virtue of the internal argument being a body part; verbs that involve the change of position of a body part do allow accusative, even in Russian, as in (1b) and (2b). The case alternation presents two problems: how is instrumental case licensed, and what is the syntactic difference that allows accusative to be licensed in both verbs in Lithuanian, but only change-of-position verbs in Russian. Following Pylkkänen 2008 and Lavine 2010, I assume that the argument-introducing and transitivity properties of v are split between two functional heads, v-VOICE and v-CAUSE, respectively; see (3). Russian and Lithuanian differ in which v’s can merge with the V root: both allow v-VOICE, but only Lithuanian allows v-CAUSE, and thus accusative case. This is further supported by the morphology of verbs of making sound, many of which have the old causative suffix -(d)y-/-(d)in-. In the intransitive, non-causative versions of such verbs, accusative is barred (Ambrazas 2007). The instrumental case is a property of V (or licensed below v), assuming unaccusative predicates do not have vP shells. However, the instrumental is not licensed without the presence of an external argument, thus it is dependent both on the verb and the syntactic environment. Svenonius 2006 proposes a similar bipartite case-licensing structure for accusative and dative in Icelandic: accusative requires V and AgrO (under my analysis, vCAUSE) while dative requires VD and a higher VOICE head. I propose that instrumental is licensed in verbs of moving body parts (by v-VOICE and VI), dyadic verbs of sound (v-VOICE and VI), and is absent in the monadic verbs (no v-VOICE to check instrumental). Also, this allows the instrumental on the causative Lithuanian verbs of sound; it is licensed by checking a case feature on V and the v-VOICE head, despite the presence of v-CAUSE. I will also argue that the accusative, allowed in Lithuanian for both types of verbs and on Russian change-of-position verbs involving body parts, does not come from a lack of the instrumental feature on the V. Rather, these verbs always occur with the feature to license instrumental, but a difference in event structure allows the accusative to override the instrumental. Because the accusative in the Lithuanian alternation yields an interpretation of affectedness, it can be considered a telic predicate when this case occurs (Tenny 1994). Following Ramchand 2008, the telicity is due to the presence of a result subevent, which is represented in the syntactic structure as a R(esult) head. This head hosts an argument, the holder of the result, which can remerge as the internal argument (an UNDERGOER in Ramchand’s terminology), as shown in (3). If accusative is linked to telicity (cf. Richardson 2007), then the NPi in (3) gets a case feature from telicity head R, and the instrumental feature of V is not licensed on the internal argument. The accusative case feature must still check on the higher v-CAUSE head, which is why the non-causative verbs of sound never allow accusative. By decomposing the verb phrase into the subevents it entails, we see the relationships between event structure and argument structure, and by extension, case. (1) a. Anna požala *pleči/✓plečami Anna shrugged shoulders.ACC/INST ‘Anna shrugged her shoulders’ b. Anna skreščivala nogi/*nogami Anna crossed legs.ACC/*INST ‘Anna crossed her legs’ RUSSIAN c. Okhrannik brenčal *ključi/✓ključami guard jingled keys.ACC/INST ‘The guard jingled the keys’ d. Ključi/*ključami brenčali v karmane keys.NOM/*INST jingled in pocket ‘The keys jingled in the pocket’ (2) (3) a. Ona traukė pečius/pečiais LITHUANIAN Ona shrugged shoulders.ACC/INST ‘Ona shrugged her shoulders’ b. Ona sukrižiavo kojas/*kojomis Ona crossed legs.ACC/*INST ‘Ona crossed her legs’ c. Apsaugininkas žvang-in-o raktus/raktais guard jingle-CAUS-PST keys.ACC/INST ‘The guard jingled the keys’ d. Raktai/*raktais žvangėjo/*žvang-in-o kišinyje keys.NOM/*INST jingled/*jingle-CAUS-PST pocket.LOC ‘The keys jingled in the pocket’ [[v-VOICEP NP:EA v-VOICE’ v-VOICE]] v-CAUSEP v-CAUSE VP V’ NPi VI Res NPi Bibliography Ambrazas, V., et al., eds. 2007. Lithuanian grammar, 2nd ed. Vilnius: Baltos Lankos. Chomsky, N. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Kittilä, S. 2009 “Case and the typology of transitivity”, in Andrej Malchukov & Andrew Spencer (eds), The Oxford handbook of case. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 356-65. Lavine, J. 2010. Case and events in Transitive Impersonals. Journal of Slavic Lingusitics 18(1), 101-130. Pylkkänen, L. 2008. Introducing arguments. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Ramchand, G. 2008. Verb meaning and the lexicon: a first-phase syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Richardson, K. 2007. Case and Aspect in Slavic. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Svenonius, P. 2002. “Icelandic Case and the Structure of Events.” Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics, 5. 197-225. Svenonius, P. 2006. “Case alternations and the Icelandic passive and middle”. Ms., lingBuzz/000124, downloaded 10/28/08. Tenny, C. 1994. Aspectual roles and the syntax-semantics interface. Dordrecht: Kluwer. Wierzbicka, A. 1980. The case for meaningful case. Ann Arbor, MI: Karoma.