The costs of decline in manufacturing

advertisement

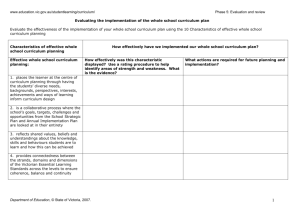

4 The costs of decline in manufacturing 4.1 Introduction Manufacturing’s share of output and employment in the economy has fallen as other sectors have performed strongly. The terms of reference instruct the Commission to report on the costs to the Victorian economy of the manufacturing sector continuing to decline relative to the growth of other sectors, including services. The relative decline in manufacturing has given rise to concerns that this deterioration may impose costs on the wider community. This chapter provides an overview of the Victorian economy within the Australian context; explores the extent and composition of structural change in the Victorian economy; and considers the possible costs of the relative decline of manufacturing. 4.2 The economic context: A picture of growth and rising incomes Globally, Victoria and Australia are not alone in experiencing a declining share of manufacturing in the economy (see chapter 2). Indeed, in many countries the rate of decline has exceeded that in Victoria. Chapter 3 discussed the key drivers of the performance of manufacturing. Change in the manufacturing sector is ongoing, driven by factors such as the exchange rate, strong global competition, and the expansion of the mineral sector, which is drawing resources from other sectors: While manufacturing is important to our economy — and its activity levels have not diminished in absolute terms — the reality is that its relative decline has been integral to the marked increase in the living standards of Australians. (Banks 2011, p. 12) Overall, the declining share of manufacturing in the economy has coincided with strong performance in the Australian economy as a whole, as indicated by growth in national income, per capita incomes, population, and falling unemployment. Much of the growth over the last five years has been driven by the resources boom, with strong demand from China and India. Recently, the mining industry has increased its share of investment, output and exports, and has contributed to an increase in Queensland’s and Western Australia’s share of the Australian economy. THE COSTS OF DECLINE IN MANUFACTURING 51 Even though Victoria’s economy is not well endowed with mineral resources, its economic growth is close to the national trend, as shown in figure 4.1. 1 Victorian GSP grew by 3.0 per cent per year over the last twenty years, slightly below the national annual growth rate of 3.2 per cent. Also, Victoria’s income per capita (growing at an average annual rate of 1.8 per cent) has largely grown in line with the national trend (average annual rate of 1.9 per cent), as shown in figure 4.2. This suggests that other sectors and forces have kept Victorian output, employment and incomes growing, even though manufacturing’s relative contribution to growth has fallen. Figure 4.1 Australian Real GDP and Victorian Real GSP, 1989-90 to 2009-10 ($ billions) 1,400 350 1,200 300 1,000 250 800 200 600 150 400 100 200 50 0 1989-90 0 1993-94 1997-98 Australia (LHS) 2001-02 2005-06 2009-10 Victoria (RHS) Source: ABS 2009c; ABS 2009d. Real Gross State Product (GSP) and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) are based on a chain volume measure and 2008-09 as the reference year. Per capita indicators measure the ratio of the chain volume estimates of GDP and GSP to an estimate of the resident Australian and Victorian populations. 1 52 VICTORIAN MANUFACTURING: MEETING THE CHALLENGES Figure 4.2 Australian Real GDP and Victorian Real GSP per capita, 1989-90 to 2009-10 ($ per annum) 70,000 60,000 50,000 40,000 30,000 20,000 1989-90 1993-94 1997-98 2001-02 Australia 2005-06 2009-10 Victoria Source: ABS 2009c; ABS 2009d. There is, however, evidence that real weekly earnings in Victoria are lagging behind the national average (figure 4.3). Figure 4.3 Real Average Weekly Earnings, Australia and Victoria, 1994-95 to 2009-10 ($) 1,000 950 900 850 800 750 700 1994-95 1996-97 1998-99 2000-01 2002-03 Australia 2004-05 2006-07 2008-09 Victoria Note: Average weekly earnings expressed in average 2010 dollars; converted into real terms using the consumer price index. Source: ABS 2011b. THE COSTS OF DECLINE IN MANUFACTURING 53 Victoria’s population growth has also risen dramatically since the early 1990s, averaging around 1.6 per cent over the past decade, while the national average has been similar at 1.5 per cent (figure 4.4). Victoria’s population grew by 2.2 per cent over 2008-09, the highest rate over the last two decades. Much of the continued increase in Victoria’s population has resulted from its rising share of national net overseas migration, which makes up two thirds of Victoria’s population increase. Figure 4.4 Population growth rate, Australia and Victoria, 1989-90 to 2009-10 (per cent) 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 1989-90 1993-94 1997-98 Australia 2001-02 2005-06 2009-10 Victoria Source: ABS 2010c. National and state unemployment rates have declined significantly since the early 1990s (figure 4.5). In the early 1990s, Victorian unemployment exceeded the national rate. Since that time, Victorian unemployment has been broadly in line with the national level (currently 4.9 per cent (ABS 2011e)), despite national labour market conditions favouring employment in the mining and service industries and manufacturing employment continuing to decline.2 Recent trends suggest that manufacturing employment in mining related firms is receiving a boost from the expansion of the resources sector, while more trade-exposed parts of the sector are contracting under pressure from the high exchange rate (RBA 2011c, p. 38). 2 54 VICTORIAN MANUFACTURING: MEETING THE CHALLENGES Figure 4.5 Unemployment rate, Australia and Victoria, 1989-90 to 2009-10 (per cent) 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 1989-90 1993-94 1997-98 Australia 2001-02 2005-06 2009-10 Victoria Source: ABS 2011e. Overall, the decline in manufacturing’s share in Victoria’s economy over the past decade does not appear to have significantly held back economic or employment growth. 4.3 Structural adjustment Underlying Victoria’s recent strong economic performance is considerable change in the structure of the economy. Structural change occurs when industries grow at different rates and the composition of the economy shifts. These variations in output, employment and productivity growth among industries, including the manufacturing sector, are part of ongoing economic processes. Figures 4.6 and 4.7 present structural change indices for Victorian output and employment respectively.3 Where changes in shares are small, the value of the index is small, indicating modest structural change. Conversely, where changes in shares are large, the index is larger, indicating more extensive structural change. This analysis suggests that the rate of structural change in the output of different industries in Victoria decelerated over the decade to 2010, as depicted by the average trend line (dashed line in figure 4.6). Similarly, rates of change in the The methodology follows that of Productivity Commission (1998) and Connolly and Lewis (2010). See Appendix B for a description. 3 THE COSTS OF DECLINE IN MANUFACTURING 55 industry composition of employment have fallen over the last decade, also shown by the average trend line (dashed line in figure 4.7).4 Figure 4.6 Structural Change Index for Victoria – Outputbased, 1990 to 2010 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 Note: dashed line represents an average trend. Source: VCEC. Structural change indices are sensitive to the level of aggregation underlying the industry classification and time period. 4 56 VICTORIAN MANUFACTURING: MEETING THE CHALLENGES Figure 4.7 Structural Change Index for Victoria – Employment-based, 1990 to 2010 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 Note: dashed line represents an average trend. Source: VCEC. The larger changes in manufacturing compared with other sectors have contributed to this structural change. While the contribution of manufacturing has varied considerably from year to year, on average manufacturing contributed about 35 per cent of the shifts in employment in the economy, much larger than its share in the economy (figure 4.8). Gary Banks remarked: In Australia’s case, the decline of manufacturing has looked more pronounced than elsewhere only because of its artificially elevated starting point — underpinned by high protection. (Banks 2011, p. 5) However, the trend lines for this time series, as for the other measures of structural change, appear to have declined for Victoria. THE COSTS OF DECLINE IN MANUFACTURING 57 Figure 4.8 Contribution of Manufacturing to Structural Change in Employment for Victoria, 1990 to 2010 (per cent) 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 Manufacturing Contributions to Structural Change Employment Share of Manufacturing Note: dashed line represents an average linear trend. Source: VCEC. In the past, much of the structural adjustment has been driven by innovation and improved productivity, against a background of reductions in industry assistance and adjustment programs. More recently it has also been driven by the high exchange rate. The inquiry heard that many Victorian manufacturers are adjusting, or have already adjusted, to the new business environment characterised by ongoing change and intense competition from other local and foreign firms. Sutton Tools remarked: The waves keep coming. We must learn how to surf, and keep an eye out for sharks, and the occasional rip. (Bendigo Business Forum, April 2011) Some other companies have increasingly moved their production activities off shore, especially the price-sensitive activities. The Commission considers it is possible, however, that reductions in manufacturing output and employment may accelerate in the near term. This is discussed further in section 4.6. 58 VICTORIAN MANUFACTURING: MEETING THE CHALLENGES 4.4 The costs of decline Notwithstanding Victoria’s overall strong economic performance and the changing structure of the economy, it is important to consider the possible costs of the relative decline of manufacturing. These include the costs of structural adjustment long-term unemployment and loss of industries. AME Systems argued that the continuing decline of the manufacturing sector in Victoria’s economy could include employment, technology and strategic losses (sub. 13, pp. 8-9). The Commission has adopted a community-wide perspective, which involves assessing total social costs and benefits resulting from the decline of manufacturing. 4.4.1 Costs associated with unemployment The links between structural change and unemployment are not clear. Measuring the effects on unemployment of structural change is beset by difficult empirical and methodological issues (PC 2003a, p. 45). Different analytical approaches have tended to provide different conclusions. Over the long run, there does not appear to have been a strong relationship between unemployment rates and structural change in the economy (PC 2003a, p. xviii). Moreover, while there is evidence of short-term effects in periods of major change before the GFC, in other periods structural adjustment in manufacturing appears to have had weaker short-run effects on unemployment (PC 2003a). In Victoria, the strong growth in overall employment suggests that the relative decline in manufacturing has not had a significant negative impact on aggregate employment over the longer term. Nevertheless, pockets of manufacturingrelated unemployment may have caused significant personal and social costs (see section 4.6).5 The social and personal impacts of long spells of unemployment can be very high for those affected. At a national level, Borland and Kennedy (1998) showed that individuals losing their jobs in manufacturing had lower re-employment prospects than in other industries owing to their age, education levels and location.6 This study is dated, however, and the upskilling of manufacturing workers may have made the study’s results less relevant today. The very limited recent evidence on the impact Structural changes have affected the ability of workers to move between jobs and industries. Attributes such as poor English proficiency, older age and low educational attainment are major indicators of increased risk of unemployment (PC 2003a, p. xxiv). 5 Also see Borland (1996) and Borland and Foo (1996) for earlier research on the composition and dynamics of employment in Australian manufacturing. Li (2011) reported that the number of manufacturing workers leaving the workforce is considerably smaller than those shifting to non-manufacturing sectors. 6 THE COSTS OF DECLINE IN MANUFACTURING 59 of manufacturing-related unemployment in Victoria prevents a thorough examination of this issue. Nevertheless, changes in the structure of employment across regions affect employment opportunities, rates of unemployment, levels of household income and patterns of regional migration. The Commission has focused on the movements in metropolitan Melbourne and regional unemployment rates, and considered whether this coincided with areas where manufacturing employment has been lost. Since the early 1990s, the regions have had higher rates of unemployment and long-term unemployment than metropolitan Melbourne (figures 4.9 and 4.10 and table 4.1). However, as noted in chapter 5, regional Victoria has seen relatively stable manufacturing employment over the past decade, which suggests that job losses in manufacturing have not been a major contributor to regional unemployment overall, even though job losses may have been relatively significant in particular towns. Nevertheless, some regions in Victoria with a small number of major employers are more vulnerable to these circumstances. Figure 4.9 Unemployment rates for Melbourne and Regional Victoria, 1990 to 2011 (per cent) 14.0 12.0 10.0 8.0 6.0 4.0 2.0 0.0 1990 1993 1996 1999 Melbourne 2002 2005 2008 2011 Regional Victoria Source: ABS 2011e. 60 VICTORIAN MANUFACTURING: MEETING THE CHALLENGES Figure 4.10 Long-term unemployment rates for Melbourne and Regional Victoria, 2000 to 2011 (per cent) 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Melbourne 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Regional Victoria Source: ABS 2011e; ABS 2009a. The differences between unemployment rates in Melbourne and the other major statistical regions in Victoria are provided in table 4.1. In the late 1990s, Gippsland’s unemployment rate was, on average, 2.8 percentage points higher than Melbourne’s. More recently, higher rates of unemployment (on average 2.2 percentage points) are evident in the Central Highlands-Wimmera region, which includes Ballarat. THE COSTS OF DECLINE IN MANUFACTURING 61 Table 4.1 Unemployment rate differential between Melbourne and major Victorian statistical regions, 1993-2010 (percentage points) Barwon-Western Central Highlands- Loddon-Mallee Goulburn-OvensWimmera Murray 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Average -0.5 0.6 1.2 0.6 2.5 1.1 1.4 1.3 -1.2 -0.4 0.1 2.0 1.6 1.7 0.4 -0.9 0.2 0.5 0.7 2.9 0.8 0.2 0.6 0.6 1.6 0.9 0.8 0.7 1.4 0.8 2.4 1.4 3.4 2.6 2.3 0.5 2.4 1.5 1.3 1.4 0.6 -0.1 1.1 0.6 1.4 0.9 1.9 -0.1 -0.7 2.2 1.7 1.7 0.8 1.2 0.2 1.6 1.0 -3.2 -2.3 -1.9 -1.8 -1.7 -0.3 -1.6 0.4 -1.0 -0.3 -1.6 -1.1 0.7 -0.0 -1.4 0.3 -0.4 1.3 -0.9 Gippsland 2.7 2.4 -0.3 1.1 3.3 3.7 3.3 2.7 2.0 2.1 0.7 1.6 2.8 0.0 1.3 0.1 -1.0 0.4 1.6 Source: ABS 2011e; ABS 2009a. 4.4.2 Loss of industries Another potential cost of structural change is the loss of a strategic industry or skill. It has been suggested that, once an industry falls below a minimum size, it can reach a tipping point below which the whole industry is lost. For this to involve costs in addition to the adjustment costs noted above, there must be external benefits associated with the existence of the industry which are lost once it has gone. The Australian Council of Wool Exporters and Processors expressed the concern that, if the current wool processing plants were lost, there would be flow-on effects and broader costs to the industry (sub. DR52, p. 6). Similarly, the Federation of Automotive Products Manufacturers (FAPM) pointed out that, in the case of the automotive industry, the threshold level of activity is primarily driven by the production of locally manufactured vehicles. 62 VICTORIAN MANUFACTURING: MEETING THE CHALLENGES The loss of volume in local vehicle production would likely have a significant impact on the businesses and trades associated with the industry, such as the tooling industry, raw material suppliers and the services sector (sub. DR60, p. 10). Toyota Australia also acknowledged that the local automotive manufacturing sector is a strategic industry, and is at risk if volumes continue to decline while operational costs continue to rise (sub. DR64, p. 10). While some groups have argued for special treatment to avoid loss of particular industry, it needs to be recognised that changing industry structure is a normal part of economic growth. There is also considerable debate about what is (or is not) a strategic industry, what the broader net benefits to the community of supporting such industries are and whether, in practice, it is possible for governments to override broad market trends. This is discussed further in chapter 6. Whether there is evidence of the loss of training capacity for key skills is discussed in chapter 9. 4.4.3 Costs from structural adjustment Adjustment costs arise when labour and capital in contracting parts of the economy do not move readily at low cost to those parts of the economy where they can earn a competitive return. These costs may include re-skilling displaced employees, under-utilised capital and unused assets. Some level of adjustment costs is inevitable. The challenge is to minimise them and reduce the impacts on individuals, households and communities. In fully employed economies with well functioning markets, adjustment costs are usually low. The Commonwealth Treasury details an example of a Victorian community successfully making such a structural shift and facing the challenges of adjustment (box 4.1). THE COSTS OF DECLINE IN MANUFACTURING 63 Box 4.1 Geelong – adapting to change Founded in the 1830s, Geelong became one of Australia’s premier port towns. In the second half of the 19th century, it shipped the agricultural exports of western Victoria around the world. In the 20th century, rapid advances in technology and the advent of mass production techniques provided a new economic opportunity for Geelong. A strong manufacturing sector emerged, providing work for Geelong’s growing population. Large firms, such as Ford, also spawned a wide range of related and supporting industries. In the early 1990s, the recession and the collapse of the Pyramid Building Society hit the Geelong region hard. Mirroring events in the broader economy, jobs were also lost in textiles, clothing, footwear and leather manufacturing. The population declined and the region was under pressure. Some firms opted to relocate or close. Developments in technology also meant that certain occupations became redundant. Yet new technologies and a competitive economic environment provided new opportunities and generated improved living standards. Many manufacturing firms abandoned traditional, labour-intensive modes of production. Firms, including those in the growing biotech industry, switched to capital-intensive and knowledgeintensive approaches. These firms focused on research and development and required workers with design, engineering and science skills. While manufacturing is still a large employer in Geelong, employment in services (across a range of areas) has grown considerably over the past decade. Source: Commonwealth Treasury 2011a, p. 31. In the past this adjustment has often been accompanied by government programs to facilitate change and reduce its impact on communities. Ai Group suggests that state government assistance programs, such as the Industry Transition Fund (ITF) and other national programs, are important in assisting the manufacturing sector to adjust to structural change (sub. DR55, p. 23). More specific to the automotive industry, the FAPM pointed out those programs that aimed to facilitate structural adjustment, such as the Automotive Industry Structural Adjustment Program (AISAP), did in fact assist the industry (sub. DR60, p. 7). Toyota Australia recommends a broad approach to setting appropriate policy settings to allow a transition through the current challenging market (sub. DR64, p. 10). The arguments around structural adjustment assistance are complex. If poorly applied, or in inappropriate circumstances, such assistance can have a range of problems (including distorted incentives leading to protracted adjustment, rent seeking behaviour and difficulties in ceasing the assistance once granted) and may adversely affect other industries by reducing employment prospects elsewhere in the economy. That said, the case for government action is clearest when industry closures have a significant impact on local workers who need assistance to retrain or move into alternative employment. In this case assistance is provided for a very specific 64 VICTORIAN MANUFACTURING: MEETING THE CHALLENGES purpose and for a defined period of time. Business, however, sometimes claim that assistance is also warranted in other circumstances. For example, during a temporary economic downturn some may claim that assistance is needed so that vital skills and business capacity are not lost when the business would viable in the long term. This was part of the justification for changes to the Victorian Industry Participation Policy (VIPP) in (see chapter 12). The submission by the Australian Manufacturing Workers Union, the Australian Workers Union and the National Union of Workers argued that unfavourable movements in the currency exchange rate are a justification for assistance: There is no economic justification for sitting on the sidelines and watching unless the policy authorities have a very high degree of certainty that the terms of trade and the dollar are fixed at these high levels for a decade or more and that structural adjustment and the allocative efficiency function of markets must therefore be left unfettered to redistribute capital and labour to their most efficient uses. The precautionary principle and considerable expert opinion suggests the high dollar is unlikely to be with us for a decade or more that case for intervention is strong to secure those capabilities that would otherwise be lost. (sub. DR58, p. 28) Others have argued that in some cases the rate of change and investment needed to revitalise or restructure industry is beyond the capacity of the affected industry. They argue that government assistance to support the transition would avoid massive adjustment costs. In such cases it has also been argued that the risks of significant adjustment costs are particularly acute when the vulnerable businesses are part of a broader supply chain and the closure of a few businesses puts the whole supply chain at risk. In this regard the FAPM suggested that automotive companies are seeking government assistance to help them with internal restructuring and diversification, and that previous grants under the ITF had encouraged automotive supply chain consolidation (sub. DR60, pp. 7-8). Supply chain issues were also raised by Toyota: It is important to note that a continued decline in the manufacturing sector will lead to the eventual loss of the local automotive manufacturing industry. The flow on effects of this would impact the entire automotive supply chain, as well as service providers to the industry. (sub. DR64, p. 3) Toyota argued that automotive manufacturing requires appropriate policy settings to allow a transition through the current challenging market situation including: automotive Component Supplier specific policy and programs to facilitate: accelerated consolidation and rationalisation of the auto components sector assistance to develop diversification opportunities access to debt finance. (sub. DR64, p. 9) THE COSTS OF DECLINE IN MANUFACTURING 65 Due to the complexity of each of these issues it is important that they are carefully considered on a case-by-case basis to ensure that the benefits of any proposed assistance outweigh the costs. In assessing those costs and benefits it is also necessary to demonstrate that: the problem that the assistance is intended to address is expected to be very temporary or a one-off permanent restructuring is needed that would result in a viable, and competitive industry the industry would be viable in the long-term without further assistance supporting the industry would not be at the expense of the competitiveness of other sectors. The Commission has not undertaken such an assessment on the assistance programs offered to the Victorian manufacturing sector. However, the Commission agrees in principle with the value and appropriate role of adjustment programs, properly defined and focused. The Commission’s views on the appropriate role for government programs are discussed later in this report (see chapter 6). 4.5 Social costs of decline Decline in manufacturing can lead to businesses closing permanently or moving to another location. Unemployment is one possible outcome, or workers move, seeking employment in another region. While this process is economically efficient, and may benefit Victoria in the longer run as average incomes and levels of welfare are higher, individuals and communities may incur significant costs which should not be ignored. Watts and Mitchell argue that ‘the majority of commentators agree that sustained unemployment imposes significant economic, personal and social costs that include’: 66 loss of current output social exclusion and the loss of freedom skill loss psychological harm ill health and reduced life expectancy loss of motivation the undermining of human relations and family life racial and gender inequality loss of social values and responsibility. (Watts and Mitchell 2000, p. 5) VICTORIAN MANUFACTURING: MEETING THE CHALLENGES 4.5.1 Costs to individuals As noted in section 4.4.2, unemployment — especially long-term unemployment — can impose significant costs on individuals, beyond loss of income. Burgess and Mitchell note that: Unemployment has been linked to family break up, substance abuse, alienation, discrimination, illness and death, truancy and non-completion of schooling, and poverty. (Burgess and Mitchell 1998) In addition, unemployment not only affects the direct well-being of the individual but also their ability to enjoy the rights and privileges expected by other members of the community: In the context of human rights it is important to emphasise the loss of freedom associated with unemployment. Without access to labour income the unemployed have to rely on social and/or family transfers, non-labour income or savings. For many of the unemployed there is no pool of savings, no nonlabour income and no family transfers. Being without an income severely restricts the ability to participate in the market economy. (Burgess and Mitchell 1998) 4.5.2 Impact on communities Decline in local manufacturing industries can affect community strength and resilience — especially in regions where there is a single major employer. As well as leading to pockets of unemployment, major business closures or contractions can break up communities, as workers leave to find employment elsewhere. Unemployment and social exclusion can also lead to direct problems in local communities. For example, Burgess and Mitchell argued that: … social and economic exclusion facilitates anti-social behaviour and fosters the growth in illegal activity as a means of generating income. (Burgess and Mitchell 1998) From a wider perspective, social exclusion and population loss can reduce social capital and weaken community connections. Social bonds in communities are important, as noted by Vinson: … we have strong factual evidence, based on a sample of more than 37,000 residents of Victoria, that areas characterised by strong connections between people, and residents’ involvement with their community, are localities protected from the most harmful consequences of social conditions like unemployment, low income and limited education. (Vinson 2007, p. 3) The loss of social bonds and connections as a result of declining industry, unemployment and population loss can weaken the community protections envisaged by Vinson, potentially exacerbating the impact of decline and population loss. THE COSTS OF DECLINE IN MANUFACTURING 67 These community impacts are not just social. The Productivity Commission identified that social capital (embodying, among other things, high levels of trust among people and strong social networks) — an outcome of strong communities — can enhance competitiveness and improve economic performance by: reducing transaction costs facilitating the dissemination of knowledge and innovations promoting cooperative and/or socially minded behaviour through individual benefits and associated social spin offs. (PC 2003b, p. 15) The transaction costs of personal and business dealings can be more efficient in strong communities because of personal networks and high levels of trust among community members (PC 2003b, p. 15). The loss of social capital as a result of a declining manufacturing in some areas — most notably in regional Victoria but also in parts of metropolitan Melbourne — may impose significant social costs on individuals as well as on their families and communities. 4.6 Future costs of decline It can be expected that structural change will continue in the future; indeed, this is desirable as it leads to a more competitive and productive economy. As noted by Banks: The longer-term trends — the relative rise of the services sector and decline of the manufacturing sector — are all a manifestation of the process of advanced economic development, which are observable in most OECD countries. (Banks 2011, p. 5) Moreover, future structural change is no more likely to be associated with long-term unemployment than it was in the past two decades, even if manufacturing’s share of output and employment continues to decline. The Commission considered a number of projections of growth of output and employment in the Victorian manufacturing sector. Goodman Fielder and Visy jointly commissioned a report, The Future for Manufacturing in Victoria (SG Heilbron Economic & Policy Consulting 2010). The report used input-output (IO) analysis, and suggested that the ‘collapse of the Victorian manufacturing industry would result in significant economic and social costs’ (sub. 9 p. 5). The report estimated that 587 000 jobs would be lost in Victoria, along with 27 per cent of household income and 24 per cent of Gross State Product (GSP) (SG Heilbron Economic & Policy Consulting 2010). However, the partial equilibrium methodology used to reach this conclusion has inherent biases that significantly overestimate the negative economic impacts. The IO analysis assumes there is a complete shut-down of the manufacturing 68 VICTORIAN MANUFACTURING: MEETING THE CHALLENGES sector and adds the flow-on effects to, for example, industries that supply manufacturers. The predicted outcomes are unlikely because: The complete loss of manufacturing is an extreme scenario. It is inconsistent with recent history where some areas of manufacturing are growing even with high wages and an appreciating exchange rate. The IO analysis assumes that all people and capital employed in manufacturing would remain idle if manufacturing businesses closed. As Victoria’s and Australia’s economies are growing and many of the skills employed in manufacturing are in demand in other sectors of the economy, the decline in manufacturing would tend to be offset as these people and other resources moved into other activities. For a discussion of concerns with this methodology, and the advantages of competitive general equilibrium modelling as an alternative approach, see (Layman 2002) and (VAGO 2007a).7 The Department of Business Innovation commissioned KPMG to develop projections of the Victorian manufacturing sector (KPMG 2011b). KPMG used a computable general equilibrium model that is designed to take account of flowon effects and adjustments in the economy.8 The results for a set of ‘business as usual’ assumptions — where major drivers of domestic economic growth such as productivity, population and world growth continue in line with current trends and there are no major shifts in government policy — indicate that Victorian manufacturing output is expected to grow slowly in the next ten years (+1.0 per cent per annum), before accelerating to a higher long run average annual growth rate (+1.8 per cent per annum) owing to stronger downstream business investment (particularly mining) and projected depreciation of the Australian dollar (KPMG 2011b, p. 27). Employment in the industry is expected to contract over the long term, declining from approximately 305 000 jobs in 2010-11 to 279 000 jobs in 2030-31 (KPMG 2011b). This reflects the shift away from labour intensive to more capital intensive production processes due to the competition from overseas with lower cost labour intensive imports (KPMG 2011b, p. 27). In addition, Ai Group modelled the potential impact of a further decline in the manufacturing industry on the regions. This analysis showed significant declines in regional gross domestic product for two scenarios — a 10 per cent reduction in food manufacturing export demand, and a cumulative 10 per cent reduction in The Victorian Auditor-General compared alternative modelling techniques for estimating the economic effects of the 2005 Australian Formula 1 Grand Prix. 7 8 For full description of the model see KPMG (2011b). THE COSTS OF DECLINE IN MANUFACTURING 69 the level of total factor productivity of the manufacturing industry over 10 years (sub. DR55, pp. 36-38). Regional manufacturing is discussed further in chapter 5. 4.7 Conclusion Overall, the Australian and Victorian economies have performed well in recent years, with significant changes in their size and composition and in the distribution of activity and resources among firms, industries and regions. Although manufacturing has been a significant contributor to structural change in Victoria, the rate of structural change appears to have been decelerating. However, there may be some acceleration in this over the course of the next few years as the resources boom (along with high terms of trade and an appreciating exchange rate) accelerates this process. Structural change is an inevitable part of a growing economy, and there will always be a need to adjust. The costs of adjustment can be large if there are unemployed resources, particularly labour. Because of the personal and social costs of unemployment, the community is particularly concerned when structural change results in job losses, and the affected employees are unable to quickly reenter the workforce or alternative pathways such as re-training. Therefore, at the state level, skills and training policies are particularly important. The Commission concludes that the net costs of the relative decline in manufacturing have not been large from an economy-wide perspective, although the personal and social costs of unemployment, and losses accruing to owners of enterprises that have become uncompetitive, can be significant for those affected. To the extent that the relative decline in manufacturing has been associated with productivity growth and innovation, it is likely to have generated net benefits for the community. A key aspect of the costs of decline in manufacturing is the risk that future policy settings will not be amenable to a high-productivity, dynamic and flexible economy. Government policy is unlikely to be able to reverse the relative decline in manufacturing; to the extent it could, this would have very high direct and indirect costs. The subsequent chapters of this report focus on how to give manufacturing the best possible chance to succeed in a challenging environment. Manufacturers will have some specific needs regarding education and skills, for example, but policy interventions should operate in a non-discriminatory, broad-based way that enhances productivity and competitiveness and provides the appropriate policy settings for all firms. If future productivity growth is lower because, for example, policy prevents adjustment, or discourages innovation or the development and application of skills, this would undermine manufacturing’s long-term competitiveness. 70 VICTORIAN MANUFACTURING: MEETING THE CHALLENGES