Standing and Rights of Action in Environmental Litigation By Roger

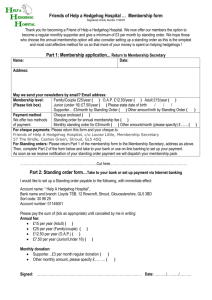

advertisement