8. "Conditional" Unionists

advertisement

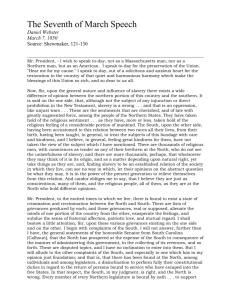

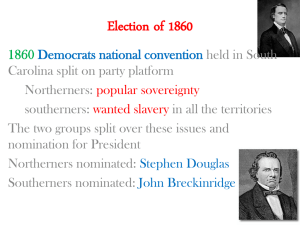

Chapter 8 November 12, 2004 “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy * Richard J. Sweeney McDonough School of Business Georgetown University 37th and “O” Streets, NW Washington, DC 20057 (O) 1-202-687-3742 fax 1-202-687-7639, - 4130 email sweeneyr@georgetown.edu Abstract: Eleven southern states seceded from the United States in 1860 and 1861. This soon led to the Civil War, in which over 600,000 military members died. One way of thinking about this burst of secession is that it resulted from a conspiracy of the so-called “fire-eaters,” who stampeded citizens who were conditional unionists. Conditional unionists had more or less strong attachments to the federal union, but could imagine leaving the Union under some circumstances. The member states of the EU have many conditional unionists. Eventually there may be influential fire-eaters dedicated to secession, and these fire-eaters may be able to stampede the citizens of a number of member states into secession. *The author is grateful for comments to Kevin Roe and Doria M. Xu. November 5, 2004 Chapter 8 “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy * Abstract: Eleven southern states seceded from the United States in 1860 and 1861. This soon led to the Civil War, in which over 600,000 military members died. One way of thinking about this burst of secession is that it resulted from a conspiracy of the so-called “fire-eaters,” who stampeded citizens who were conditional unionists. Conditional unionists had more or less strong attachments to the federal union, but could imagine leaving the Union under some circumstances. The member states of the EU have many conditional unionists. Eventually there may be influential fire-eaters dedicated to secession, and these fire-eaters may be able to stampede the citizens of a number of member states into secession. Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 2. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy Polls show that residents of European Union member states acknowledge various percentages of euro-skepticism, as Table 1 shows (EUROBAROMETER 61, Spring 2004). Measuring the degree of euro-skepticism is difficult, but for practical purposes, it might be taken as the percentage of respondents who do not believe that European Union membership is a “good thing” (question 1) or that their country benefits by EU membership (question 2) Those countries who have less than a majority saying they believe that European Union membership is a good thing (and the percentage) are Germany (45%), France (43%), Austria (30%), Sweden (37%), the U.K. (29%) and the EU15 (48%). In every EU15 country, at least 25% did not respond “yes.” (The ‘Appendix to “Conditional” Unionists’ contains more detailed responses to the questions in Table 1.) The lack of enthusiasm for the EU may be thought of as reflecting conditional support for continued membership in the EU. In the United States in the thirty years before secession and the start of the Civil War in 1861, many Southerners displayed “conditional” Unionism—they supported the Union, but under some circumstances would support secession from it. It is worthwhile examining the lessons of conditional Unionism in the U.S. for possible lessons for the stability of the EU. Of course, this period in U.S. history was roughly 150 years ago, and the issues were very different from those facing the EU, but some of the analogies are striking. Chapter 7 discussed secession in the U.S., focusing on the issues that brought up demands for secession. Of course these issues are different from issues that irritate the EU "conditional" unionists. In particular, the EU has no analogue to slavery, the issue that destroyed the Union. Other issues that led to secession pressure, such as opposition to wars or other types of defense activity, or opposition to domestic or foreign political activity, have EU analogues. Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 3. This chapter looks at the mechanisms by which pressures for secession were exerted in various southern states. In particular, so-called fire-eaters worked hard and long in the Deep South and border slave states to generate secession. They focused on propaganda, but also on various types of conspiracies to push the southern states to secession. They worked and failed for decades, often failing ludicrously. Sometimes their failures set them back for a decade or more. Often they were dismissed in the South, let alone the North, as buffoons. Eventually, however, they achieved their goal of secession. As long as they had "conditional" unionists to work with, they always had another chance to succeed, and they only needed to secede once. There are many "conditional" unionists in the EU, and there are many politicians—out of the mainstream, to be sure, but still there—working to achieve secession. If the mainstream EU leaders do not pay attention to the threat of secession, the European fire-eaters may someday be as successful as their southern U.S. forerunners were in 1860 and 1861, when the Union split apart. 1. The South Carolina Conspiracy over Tariff Nullification By the mid-1820s many Southerners were deeply opposed to the protective level of tariffs the federal government imposed. The noisiest opponents were in the state of South Carolina. A number of South Carolina fire-eaters adopted a strategy designed to force a crisis with the federal government. Some of the South Carolinian plotters wanted a crisis to force the federal government to back down and reduce tariffs. Others were part of a conspiracy to break up the Union through secession. South Carolina adopted the old notion from the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798-1799, that in the face of unconstitutional federal actions a state could interpose itself between its citizens and the federal government. Further, the state might nullify an unconstitutional law, at least within its borders, declaring it null and void. South Carolina resorted to Nullification over tariffs, declaring they could not be collected on her Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 4. territory. Further, if the federal government used force against South Carolina to collect tariffs, South Carolina would secede. The hope of the fire-eaters was that the federal government would not knuckle under but would adopt policies that would force South Carolina to secede, or at least justify secession. For this purpose, the South Carolina fire-eaters communicated with other Deep South fire-eaters, who promised to do their best to support South Carolina against the federal government and even in secession. President Andrew Jackson denied that any state had the right to exercise nullification, and threatened to use force to collect the tariffs and carry out federal business within South Carolina (Remini 1988). He managed to get Congress to pass a "force bill" to justify his use of force. But he was clever and did not use force. He threatened to blockade South Carolina's coast, and to collect the tariffs at sea, and he sent ships to the Carolina coast and strengthened federal troop installations there. South Carolina got essentially no support from other southern states, though of course there were minorities of legislators in most Southern states who spoke in support. South Carolina realized that she could not compete with Jackson, and humiliatingly backed down, though she jumped at the chance to cover her humiliation by agreeing to a compromise tariff that involved relatively minor cuts spread over more than a decade.1 The fire-eaters were discredited, and could not try their conspiratorial luck again until the crisis surrounding the Compromise of 1850. 2. The “Conditional” Unionists and the Compromise of 1850. The Compromise of 1850 grew out of a series of crises brought on by the Mexican War of 1846 – 1848. This war had its roots in the United States' annexation of Texas, at its request, that President John Tyler (Chitwood 1939) forced through in 1845, despite the fact that Tyler Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 5. was a lame-duck president who had inherited his job with the death of President William Henry Harrison (Cleaves 1939). President James K. Polk (Sellers 1966, Haynes 2000, Duisinberre 2003) played a key role while president-elect in getting Texas's annexation forced through. While president, he aggressively disputed Texas’s border with Mexico, as part of a strategy to buy or seize California and much of Mexico's territory north of the Rio Grande River. In the settlement of the war, largely dictated to Mexico (Potter 1976, Haynes 2000, Duisinberre 2003), the U.S. acquired California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, approximately half of Colorado and parts of Wyoming. Southerners were among the more enthusiastic to annex Texas and acquire territory from Mexico, and Southerners provided the majority of U.S. soldiers in the Mexican War and the two leading generals, Zachary Taylor (Bauer 1989) of Louisiana and Winfield Scott of Virginia.2 A major reason for Southern enthusiasm was to acquire territory for expansion of slavery. The acquisition of Mexican territory, however, set off conflicts as some Northerners, and a few Southerners from Border States, tried to limit the spread of slavery into these territories. In particular, while the war was still going on, David Wilmot (Democrat, PA) in 1847 moved a proviso to legislation that slavery not be allowed in any territory acquired from the war (which of course did not include Texas, annexed before the war).3 The Wilmot Proviso was never passed, but was debated passionately for several years. At the same time, Northern states were passing legislation (“personal liberty” laws) making it more difficult for Southerners to recover fugitive 1 The agreement to reduce the tariff—slowly and in minor steps—over time was negotiated largely between John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, architect of South Carolina’s positions, and Henry Clay, prime mover behind the tariff. It is generally agreed that Calhoun made quite a weak deal (Freehling 1990; Niven 1988). 2 Scott and Taylor were regular army. Taylor was an officer, and Scott rose to be a general, in the War of 1812. Among the heroes of the Mexican War were a number of Southerners who were militia or volunteer officers, including (Col.) Jefferson Davis (Cooper 2000, Chp. 6.), previously congressman and later senator from Mississippi, secretary of war in the administration of Franklin Pierce (Nichols 1958), 1853 – 1857, and finally president of the Confederacy, 1861 – 1865. Another was (Maj. Gen.) John A. Quitman, later governor and senator from Mississippi, and a fire-eater who as governor tried to bring about secession (Freehling 1990). Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 6. slaves. In addition, the Gold Rush of 1849 led to California’s population booming, and California demanded admission as a state, but as a free state. In the course of the debate over the Wilmot Proviso, fugitive slaves and the admission of California, Southern “fire-eaters” demanded that the Southern states secede rather than put up with such “Northern aggression,” as many in the South called attempts to limit slavery.4 Further, extreme Southerners who were not quite fire-eaters and more moderate Southerners threatened secession if the South’s grievances were not dealt with. As a result of these political conflicts, Congress passed the Compromise of 1850, designed to settle all of the sectional conflicts over slavery. (See Potter 1976, Holt 1978, Fehrenbacher 1978, 2001, Freehling 1990.) In the aftermath of the Compromise of 1850, many Southerners pronounced themselves satisfied, even if not completely happy—they were Unionists, they said, they dearly loved the Union, and were appalled at the thoughts of the dissolution of the Union—their forefathers had played a large role in founding Union. Many of these soi disant Unionists were, however, “conditional” Unionists.5 They loved the Union, but could foresee circumstances under which they would support secession. In all of the Southern states save South Carolina, it appeared that the majority was not fire-eaters, and the state legislatures were controlled by Unionists, but “conditional” unionists. Many South Carolina fire-eaters were so unhappy with Compromise of 3 Wilmot was a "free-soil" man, opposed to slavery in these territories, but also opposed to free blacks in these territories, as were many free-soil men (Freehling 1990). 4 In the North, the war of 1861-1865 was simply called the Civil War. Not long after the end of the war, Southern writers began to search for euphemisms. An early one was the War Between the States. Others were the War of Secession (used in 1939(!) by Chitwood), the War for Southern Freedom and the Second War for Independence. A more hard-line euphemism, soon developed and taught for many years in some Southern public schools, was the War of Northern Aggression. Wheeler (2004) states she has collected more than 40 names for the Civil War. 5 Nevins (1950, Vols. I and II) discusses conditional unionism, as do Randall and Donald (1964), Fehrenbacher (1978, 2001), and Freehling (1965, 1990) Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 7. 1850 that they conspired with the governors of two other southern states6 to stampede the Deep South into secession. South Carolina, suffering a reputation as extremist and even nutty, wanted one or more Deep South states to call a convention to discuss the Compromise and decide what action to take. The fire-eaters, of course, hoped to stampede the conventions into secession. South Carolina thought it could get Alabama or Mississippi to call first for a convention, and the South Carolina could hold one right after. But the governors of Mississippi were stymied in their attempts to call conventions that had any chance of secession. Of course it became clear that there was a fireeater plot centered in South Carolina, further discrediting the fire-eaters and South Carolina. The plot was a complete failure. Even Deep South citizens were not ready for secession. But Southerners were not “unconditional” Unionists who would never support secession under any circumstances. In the end, when the Deep South, cotton states began to secede7 and then South Carolina precipitated war by firing on Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor in April, 1861, and the Border States began to secede in response to Lincoln's call for troops to protect the Union,8 unconditional unionists made up only a small minority of Southerners.9 John Tyler of 6 One of the governors was Quitman of Mississippi; his plotting backfired on him, however, and he ended up resigning before his term was over. 7 The Deep South cotton states that seceded between Lincoln’s election, November 6, 1860, and his inauguration, March 4, 1861, were South Carolina (Dec. 20, 1860), Mississippi (Jan. 9, 1861), Florida (Jan. 10), Alabama (Jan. 11), Georgia (Jan. 19), Louisiana (Jan. 26) and Texas (Feb. 1). (McPherson 1988, pp. 235, 279 – 80, Rable 1994, pp. 32 – 36. For the best discussion of the secession conventions, see Wooster 1962.) The Border States were those further North that had many fewer slaves as a percentage of population than did the Deep South States (South Carolina and Mississippi were majority black), and included the other eight of the 15 slave states, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, Missouri and Arkansas. (North Carolina and Tennessee did not have borders with free states, but had relatively fewer slaves than the Deep South states.) 8 After South Carolina fired on Fort Sumter, Lincoln issued a call for troops and Virginia (Apr. 17, 1861), Arkansas (May 6), North Carolina (May 20) and Tennessee (June 8) seceded, giving the 11 Confederate states. (McPherson 1988, pp. 282 – 283.) Likely the majority of Maryland residents did not favor secession. Lincoln flooded Maryland with troops, arrested disloyal residents, and eventually the legislature rejected secession (McPherson 1988, pp. 284 – 290). Delaware, with only two percent of its population slaves never really considered secession—besides, it had no border with a Confederate state. (Wright 1973) In Missouri, after a convention called on the issue rejected secession, a rump of the state legislature, without a quorum and on the run, voted for secession (Nov. 3, 1861) (McPherson 1988, p. 293.) Kentucky rejected secession Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 8. Virginia, former president of the U.S. eagerly supported secession (Chitwood 1939). Formerpresident James K. Polk of Tennessee had died in 1849, but while president he had often used veiled threats that the North must beware of the South would secede, and justifiably so in his view (Duisinberre 2003). Former president Zachary Taylor of Louisiana had died in office in 1850, but during the crisis over slavery in the territory ceded by Mexico, he threatened to use force to protect the Union. John Bell of Tennessee, who ran for president in 1860 as a "Constitutional Unionist" in the end declared for secession after Sumter. John Catron of Tennessee, associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, declared for the Union, but his fellow associate justice, John A. Campbell went with his state of Virginia. As is well known, Andrew Johnson of Tennessee was the only senator from the states that seceded who declared for the Union. Many Northerners misread and minimized the likelihood that a significant number of Southern states would secede. In the period from 1820 until the start of the Civil War, many Southerners threatened many times to secede if they continued to suffer from Northern aggression. These threats helped the South gain some of her aims in the Compromises of 1820, 1833 and 1850. (Freehling 1965, 1990; Fehrenbacher 1995) South Carolina made serious efforts to organize secession in 1833 and in the aftermath of the Compromise of 1850, but failed and declared “neutrality.” A rump assembly voted for secession. Sentiment swung more strongly toward the Union when a Confederate army seized Columbia, KY, on Sept. 3, 1861. (McPherson 1988, p. 296.) The Confederacy was only a step ahead of Ulysses S. Grant (Grant 1999, Fuller 1929 and 1982), who had been ordered to seize Columbia, and having missed out, seized Paducah. In mid-October, 1861, William T. Sherman was given charge of the Military Department of Kentucky (Foote 1958, Vol. I, pp. 88 – 89; Sherman 1990; Liddell Hart 1993). The Confederacy admitted both Missouri and Kentucky (Rable 1994), but the Union dominated their territory and treated these states throughout as loyal members of the Union. Missouri and Kentucky’s Confederate representatives and senators thus had “shadow” constituencies, elected by refugees and soldiers. 9 After secession, some Southern Unionists moved within Union lines. Others kept their heads down and only announced their loyalties when they supported Union administrations in occupied Southern territory, for example, Louisiana. In the hill country of northern Alabama, western North Carolina and particularly eastern Tennessee, few owned slaves and Unionist efforts were strong, ranging from passive resistance, refusal to answer the draft and even guerilla warfare against the Confederates. The western counties of Virginia seceded from Virginia and entered the Union in 1863 as the state of West Virginia. If Confederate troops had not occupied eastern Tennessee, it might have Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 9. ignominiously in both cases (Freehling 1965, 1990). Many in the North came to think that threats to secede were a combination of cynical political maneuvers and gasconade. Even those who came to think that South Carolina was sincere in its extremism believed that state was an outlier, almost wholly unrepresentative of other Southern states. Further, because many believed that a single state could not survive on its own, they thought South Carolina could be ignored—it would not act, or it would have to crawl back after a short time. Even in the face of the agitation for Southern secession that began after the Mexican War, Northerners could comfort themselves that state government leaders in the South were not secessionist—the sensible people who ran things were not extreme, it seemed. By 1857, a disunionist was governor of Alabama, however, and was re-elected to another two-year term in 1859. A disunionist was elected in South Carolina in 1858 and another in Mississippi in 1859.10 Abolitionists were a small minority in the North. Only a small minority of abolistionists actively wanted the slave states to secede—in their view, political association with slavery and slave states was morally unacceptable. Others in the North were “unconditional” Unionists, and opposed secession under all circumstances, both for their states and for Southern states. Some in the North saw major practical problems associated with Southern secession. One was control of the Mississippi River, a vital outlet for the agricultural products of the mid-west, even though the importance of railroads was growing. Another was the possibility that a Confederacy would seek to acquire territory in Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean (particularly Cuba) and perhaps South America. A third was Southern alliance with an unfriendly "Great Power," in particular either Britain or France. seceded as did West Virginia. It should be noted that these unconditional unionists were largely anti-negro, even if also anti-slavery. 10 These were Andrew B. Moore, William Henry Gist and J.J. Pettus. The disunionist Francis W. Pickens was governor of South Carolina at the time of secession in December, 1860, and the firing on Fort Sumter in April, 1861. Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 10. It is not clear that the differences between the North and the South could have been reconciled short of civil war. One view is that the country faced an “irrepressible conflict.” Another view is that the even into the later 1850s, strong leadership by wise men could peacefully have saved the Union—who can be sure that men of the stature of George Washington or Andrew Jackson would have failed? Fashions in opinion on this topic have swung back and forth over the decades since the Civil War, in part because of political issues of the time.11 Perhaps views on this issue will never become stable. Nevertheless, by the election of 1860, it was clear that a majority of the country was unwilling to have slavery spread into areas where it was not already, and a majority of the North wanted slavery eventually to end even where it was, though this was less clear. A large majority of the South, however, refused to contemplate the end of slavery and demanded its expansion into more territory, perhaps much of the territory to the south of the U.S. 3. The Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy from the mid-1850s to Success in 1860-1861. Prominent fire eaters were William Lowndes Yancey, Edmund Ruffin, Robert Barnwell Rhett, Sr. and his son Robert Barnwell Rhett, Jr. These men and others now less well-known spent twenty years or more working for the idée fixe of Southern secession, and to many they seemed to be buffoons. For example, they suffered one setback after another in working for succession, and none ever held an important job in the Confederacy. Throughout, they were agitators, speakers, writers and editors, who had little personal political success under the Union.12 Nevertheless, they saw their dream come true when the Confederacy was born in 1861; South Carolina, Mississippi and Alabama had disunionist governors at the time of the abortive secession plot in the aftermath of the Compromise of 1850. 11 Nevins, 1947, Vol. I, p. viii, is explicit about his view that just as forethought and willingness to act could have prevented the Second World War, so the Civil War could have been prevented. 12 Yancey was a prominent orator in Southern, Democratic circles and served as a U.S. congressman, with little effect. Amazingly, he thought he might win the Democratic nomination for president in 1856, and was greatly disappointed when he was not chosen Confederate president in 1861. His major appointment was one of the three Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 11. Yancey died of natural causes in 1863, but the Rhetts and Ruffin lived to see the Confederacy die—Ruffin killed himself as the Confederacy died in 1865. Their role in secession was important. It may be overstated to claim, as some authors do, that they authored a conspiracy that led to secession and thus the Civil War.13 The facts, which one may or may not want to label “conspiracy,” are well known, however. One way of viewing their secession crusade was that the fire-eaters tried to set a series of red lines that would lead to secession by a sufficient number of Southern states. Some of the red lines were requirements that the federal government take actions to protect the South from “Northern aggression.” The fireeaters of course hoped that Southerners would see federal-government actions as inadequate. The Compromises of 1820, 1833 and 1850 were adequate for both sides, however, to the chagrin of the fire-eaters. (See Chapter 7 for the Compromise of 1820.) The presidential elections of 1856 and 1860 produced another set of red lines. By 1856, the old Whig party, which had been important in both the North and South, was dead. The Democrats remained as a national party, virtually the only party in the South, and still an important party in the North. The major opposition party was the Republicans, strong in the North, with minimal support in the Border States and none at all in the Deep South. The Democrats could thus denigrate the Republicans as merely a sectional party. The Republican Party was first put together in 1854 as a combination of the old Freesoil, Know-Nothing and Whig Parties. The party drew something from each of the forerunners and Confederate representatives sent Britain. He was not suited for the job, was largely ignored, and soon returned home. The Rhetts edited the Charleston Mercury, an influential secessionist newspaper. Rhett Sr. was appointed to a U.S. Senate seat from South Carolina, but soon resigned, under pressure, leaving no mark. He was a forceful, earnest speaker, but went years without making a speech. Ruffin was a pamphleteer, writer and agricultural reformer, who served for a time in the Virginia legislature, but with little influence. When he was in his sixties, he put on the uniform of a Virginia Military Institute cadet to slip in to watch the hanging of John Brown in 1859. He claimed to have fired the first shot at Fort Sumter in April 1861. (Nevins 1950, Vols. I and II, 1959, Vol. I; Foote 1958, Vol. I.) 13 For a systematic development of this view, see Nevins (Vol. II, 1950) who reiterates it in Nevins (Vol. I, 1959). As Nevins (Vol. I, pp. 28-29) points out, this conspiracy view was prominent in a number of Southern newspaper Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 12. made bows to each, but the key plank in its platform of 1856 was that slavery would not be allowed to expand beyond the states in which it currently existed. Many in the South believed that in the absence of geographical expansion, slavery was doomed to die out. The Republicans could then be viewed as threatening the weakening and eventually the existence of slavery. The fire-eaters pushed for a red line that was important to many Southerners: no one supporting a platform like the Republicans’ must be elected, and whoever was elected must be acceptable to the South. The country did not cross the red line in 1856. A supporter of "Southern rights," a "doughface," James Buchanan of Pennsylvania (Klein 1962), was nominated by the Democrats and defeated the Republican candidate, John C. Frémont—no red lines crossed that year.14 In 1860, the fire-eaters made the red lines work, by seeing to it that the Democrats would likely not be competitive against the Republicans. Prior to the Democrats’ national nominating convention, the fire eaters succeeded in getting a number of state parties to instruct their delegations that they were to walk out unless the convention adopted a platform that supported two key Southern demands. One was the reopening of the African slave trade, banned since 1808, and the second was federal laws to protect slave property in U.S. territories not yet admitted as states. It was clear to the fire-eaters and indeed most Southerners that no one who ran on such a platform could win Northern states. Indeed, the only plausible Northern candidate, and the most popular Democratic candidate nationally, Stephen A. Douglas had made it clear that he would not run on such a platform.15 At the national convention, April 18 – 21, held by incredibly bad planning in Charleston, SC, the fire-eaters succeeded, first, in getting a two-thirds rule accounts in 1860 – 1861. Freehling (1990) does not deny conspiracy among the fire-eaters, but minimizes conspiracy as a general phenomenon among Southern leaders. 14 The Know-Nothing Party, in its last gasp, nominated former president Millard Fillmore (Rayback 1998), who ran strongly in the South and carried one state. Fillmore, a New York free-soil Whig, was elected vice president on the Whig ticket with Zachary Taylor (Bauer 1989) in 1848, and succeeded upon Taylor’s death in 1850. Fillmore was bitter when he was denied the Whig nomination for president in 1852. Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 13. imposed for nomination, and second, in having sufficient delegates walk out over the platform that Douglas could not be nominated by the necessary two thirds. The Democrats met June 18 – 23 in Baltimore to try again. Douglas would not withdraw in favor of a candidate acceptable to the fire-eaters. Eventually, Douglas was nominated by a rump of the convention that was left after many Southern delegates again withdrew. The delegates who withdrew met elsewhere in Baltimore on June 23 and nominated John C. Breckenridge (Davis 1974) of Kentucky, then vice president of the United States. Eventually, another ticket was nominated, John Bell of Tennessee and Edward Everett of Massachusetts, as “Constitutional Unionists,” based largely on former supporters of the now-defunct Whig and Know-Nothing Parties. In between the Democrats’ conventions, the Republicans met in Chicago on May 16 – 18 and nominated Lincoln, a surprise to many (Nevins 1950, Ferhenbacher 1962). He faced the Democrat Douglas, who was unlikely to win any electoral votes in the South, and the Democrat Breckenridge, who was unlikely to win any votes in the North. The Constitutional Unionists Bell and Everett were unlikely to win any votes outside the Border States. When Douglas, Breckenridge and Bell-Everett could form fusion tickets only in New York and Rhode Island (and for three of New Jersey’s seven electors), and Douglas and Breckenridge in Pennsylvania, the main hope of defeating Lincoln was that he would not carry a majority of electoral votes. (McPherson 1988, p. 232.) This would throw the choice of president into the House of Representatives, as had happened in 1800 and 1824, when Jefferson and then John Quincy Adams emerged as winners. Lincoln, however, won a majority of electoral votes, though only 39 15 An alternative interpretation is that whatever conspiracy there was aimed at denying the nomination to Douglas, rather than being aimed overtly at splitting the Democrats and ensuring the election of a Republican. Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 14. percent of the popular vote.16 The fire-eaters’ red line was crossed, and seven Deep South states seceded. The fire-eaters were somewhat split amongst themselves as to whether secession by a single state would be viable, but they strongly preferred to see a sufficiently large number of Southern state secede. First, they had grandiose visions of setting up a strong, rich Confederacy that could join the powers of the world, and this would take at a minimum the Deep South states that actually seceded after Lincoln’s election and before his nomination. Second, they correctly believed that in most of the Deep South states it would be easier to get a vote for secession if other states had already seceded and more states were likely to secede. The fire-eaters, and many others disposed towards secession, gravely underestimated the consequences of secession. They talked themselves and many others into believing that there was little or no chance that a civil war would result. Essentially, they claimed that the North would not fight. The South was too tough for the North to take on, they argued. Many in the North would violently resist any attempt to coerce the South, as former president Franklin Pierce (1853-1857) claimed.17 The North did not want to lose money by conflict with the South, it was argued. Britain and France were so heavily dependent on Southern cotton that they would not let the North fight, or if the North fought, they would soon use force to end the fight. This is an example of how people can talk themselves into believing that what they want to do will have no Lincoln won 17 states. Douglas won Missouri and three of New Jersey’s seven electoral votes (though he received 1,376,957 to Lincoln’s 1,866,452 votes), Bell-Everett won Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia (with 588,879 votes), and Breckenridge (with 849,781 votes) won the seven Deep South states that seceded before Lincoln’s inauguration, plus Arkansas, North Carolina, Maryland and Delaware. Lincoln won 180 electoral votes, 57 more than needed. If all the votes scattered across the three rival tickets had been combined, Lincoln would still have won 169 electoral votes. If the fire-eaters had not succeeded in splitting the Democrats, the results might have been different. For one thing, many state races were quite close. Nevins (1950, Vol. II, p. 313) notes that, “It was only by a margin of a few hundred votes over the nearest opponent that Douglas carried Missouri, Bell carried Virginia, Breckinridge carried Maryland, and Lincoln carried Oregon and California.” Still, if Lincoln had lost California and Oregon, he would still have won 173 electoral votes, 50 more than needed. 16 Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 15. consequences—there are always reasons why consequences might be avoided, even if in retrospect the reasons are seen as wholly implausible.18 Southerners argued strongly during the 1850s that Britain and France, but particularly Britain, were at the mercy of the South’s cotton crop (Owsley and Owsley 1959). James H. Hammond, Senator from South Carolina gave a well-known speech, “Cotton Is King,” on the floor of the Senate in 1858: “The slaveholding South is now the controlling power of the world…. No power on earth dares … to make war on cotton. Cotton is king.”19 (McPherson 1988, p. 100; see also pp. 195 – 196.) Southerners told each other, Northerners and foreigners that loss of Southern cotton would bankrupt England, cause a revolution in England,20 be worse for England than war.21, 22 British consuls in the South listened politely and passed these views on to the Foreign Office at home. The Economist and the Spectator were incredulous at the naïveté of these views and assured their readers the views were fallacious. Lord Derby, head of the Conservative Party “termed such statements the fruit of a distempered fancy.” He pointed out that loss of Southern cotton would relatively shortly be made good by cotton from Brazil and India, eventually destroying the South’s market (as happened during and after the Civil War). He 17 Franklin (Nichols 1958) was from New Hampshire, about a Northern state as possible. He was a "doughface," however, who strongly misread the North's reaction to Southern violence, as occurred when South Carolina fired on Fort Sumter. 18 The North continued to be too sanguine about Southern secession. Lincoln, for example, seriously misread the degree of support for the Union in both the Deep South and the Border States (Nevins 1959, Vol. I, p. 29). After the South fired on Fort Sumter, there was a wave of patriotic enthusiasm in the North, with many volunteers to fight. Many in the North thought victory would be quick and cheap (Nevins 1959, Vol. I, p. 75). The rebels were a small minority of the country, and their section was not industrialized and vibrant the way the North was. Some thought the whole thing was a “local commotion.” Others thought a proclamation would be enough to settle the matter. 19 Hammond became rich by marrying an ugly heiress. He notoriously took sexual advantage of his female slaves. He took sexual advantage of several daughters of his wife's brother, though stopping short of intercourse; amazingly, the family did nothing. (Freehling 1990). 20 “[A] Carolinian [told] the British consul … “Why, sir, we have only to shut off your supply of cotton for a few weeks, and we can create a revolution in Great Britain.’” (Nevins 1959, Vol. I, p. 97.) 21 “A failure of our cotton crop for three years would be a far greater calamity to England than three years’ war with the greatest power on earth.” (Nevins 1959, Vol. I, p. 98.) 22 Former President John Tyler claimed in 1850 that a major purpose of his in annexing Texas was to give the U.S. a monopoly on cotton production. “An embargo of a single year would produce in Europe a greater amount of Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 16. pointed out that in 1845 – 1849, Britain got 84 percent of her cotton from the South, and in 1855 – 1859, 76 percent (Nevins 1959, Vol. I, p. 97). Partly these Southern views were due to ignorance of foreigners and foreign conditions, and of economics. Indeed, Southerners tended strongly towards Physiocratic views that agricultural was “basic” and the source of all wealth, while manufacturing and services were somehow “artificial.”23 Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, only president of the Confederacy, was a secessionist or at best the most conditional of Unionists,24 but he was one of the very few who argued that secession would lead inevitably to civil war, and that the war would be long and costly. He was denounced for these views by the fire-eaters before secession, and by the more rabid Confederate patriots in the early days of the Confederacy (Nevins 1959, Vol. I, p. 99). 4. “Conditional” Unionists in the European Union. Surveys show that in several EU member states, the majority of the population has a negative opinion of the EU. Further, every member state has at least 25 percent who hold a negative opinion of the EU. In a few member states, a majority says the country would be better off out of the EU. In some meanings of the term, the EU contains many “conditional” (European) Unionists. Many of the poll respondents who claim their countries would be better off out of the EU are not fire eaters who really mean what they say and would vote now to leave. Some, however, could imagine circumstances in which they would vote for secession, but other circumstances in which they would oppose it. Some are simply letting off steam, and would suffering than a fifty years’ war. I doubt whether Great Britain could avoid convulsions.” Quoted in Chitwood (1939, p. 354). 23 Thomas Jefferson’s enthusiasm for a republic based on yeoman farmers was an early version of Southern Physiocratic views, and indeed Jefferson came in contact with Physiocrats and their views while he was ambassador to France in the 1780s until 1792. 24 Nevins (1950, Vol. II, and 1959, Vol. I) views Davis as a secessionist. Foote (1958) and Cooper (2000) see him as a Unionist, but it is hard to believe that his Unionism had any strength. Thomas (1979) sees him as confused about his views and ultimate goals on secession. Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 17. think long and hard before voting to secede, with perhaps a large percentage pulling back at the last moment under most circumstances. Where the euroskeptics fall along this spectrum is of conditional Unionism cannot be told from the available polls, and it is difficult to see how to sort out the degree of intensity.25 U.S. history suggests it is an error, however, to dismiss euroskeptics as a tiny, derisible minority of fire-eaters supplemented by blowhards and cynical political poseurs. Even if the conditional Unionists will currently be Unionists under almost any circumstance, in time they can change to conditional Unionists with sharp red lines beyond which they will turn to secession. No member-state government proposes seceding from the EU, but a number of member states have minority parties that favor secession (for example, the U.K. and Poland).26 It is easy to suppose that the reasonable, mainstream politicians who lead member states are the "true" representatives of the countries' people, and to dismiss the fire-eaters. Again, U.S. history suggests that leadership can change and fire-eaters can get their way. Whether the secession crisis that led to the Civil War could have been avoided, a secession crisis in the EU can be avoided and without requiring strong, wise leaders who can be expected to arise only by chance, perhaps only one in a lifetime. The conflict that can tear apart the EU is between those who want more power at the federal level and those who do not. If the federal level does not receive more power, those countries that favor further accumulation of federal power are unlikely to feel so oppressed that they have to secede; for those member states A “conditional Unionist” could be someone who says “Yes”, “No” or “Neither” in the surveys. “Neither” is a type, however, who may reasonably turn out to be, or may convert to being, “conditional.” An important issue is, when a survey question asks that “taking everything into consideration…,” does the respondent that it to mean under all possible circumstances? Does the respondent carefully consider all possible consequences? 26 Why does the EU Constitution allow secession, a provision that seems to create foreseeable instability? One suggestion is that most Europeans in most European countries do not think it is yet time to establish a country, even if a confederated country. Member states joined the EU for their own interests, instead because of a commitment to Europe as a whole. Summary of the agreement on the Constitutional Treaty (06/28/04) states “…allow us to call this basic text our ‘Constitution’… In legal terms, however, the Constitution remains a treaty…” 25 Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 18. that desire greater federalization, an alternative is to work for stronger, deeper, wider ties among a sub-set of countries agreeable to such strengthening.. It is clear, however, that if enough federal power is accumulated, then more and more citizens of more-euroskeptic member states are likely to become conditional unionists, and the strength of their conditional devotion to the EU is likely to lessen. Is France the hindrance to saving the EU from the threat of secession? For decades, France has attempted to lever its own power in foreign and defense affairs by getting the EU to back its positions. Secession Conspiracies and the European Union. For the European Union, the moral of this story is that fire-eating secessionists may often look like buffoons, may plot and fail any number of times, but may still eventually succeed in setting up red lines that are crossed and trigger secession. Possible red lines that might trigger secession are not hard to find. In every new EU treaty negotiation from Maastricht to Nice to the new constitution, various member-state governments set out red lines, and seemingly inevitably these red lines are crossed, though often with some face-saving formulation that allows the governments that set out the red lines to argue that they “really” prevailed. The more of these red lines that are crossed, the more some EU citizens become angrier and the more willing to be conditional Unionists. The so-called federalists find that over time the red lines can be passed, perhaps not as soon as desired or with as definitive language, but without consequences to the federalists. In the compromises, the federalists give up nothing save postponement of demands they had in advance of the negotiations, where some of the demands were there simply to be given up temporarily. The federalist countries are driven by genuine beliefs about the desirability of greater power at the federal level, but also by the usefulness in domestic politics of having a federalist agenda. Achieving greater federalization is to some extent a substitute for achieving domestic Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 19. political goals. Further, it may be possible to use EU federal power to achieve goals in foreign and defense policies that play well domestically. A EU constitutional settlement would essentially be one that set the limits to federalization, and took the issue of further federalization off the table.27 To the extent that euroskeptics could live with the amount of federal power in a settlement, much of the pressure for secession would be removed. In the absence of a settlement, federalist countries will push for evermore federal power, and will be reluctant to restrain themselves simply because of threats of secession. Indeed, federalist country governments that show restraint over fear of secession are simply giving their rivals a political issue to use—the rivals will “stand up” to the threats of secession. As long as the future hold an endless series of negotiations over new federal powers, a series of red lines will be crossed, because federalist countries will be unable to stop their demands. Coalitions that can temporarily stand up to the federalists may well disappear in the future. An example is the coalition of Spain and Poland that defeated the Council voting proposals in the constitution in December, 2003. Six months later, the Spanish government had changed and the Polish government thought it had little choice but to cave in. The history of (failed) attempts to unify Europe is long and discouraging. Some have even gone so far as to view Napoleon and Hitler as attempting to unify Europe. A main stumbling block to European unification is lack of cultural unity—even today, many people overstate the degree of cultural unity in Europe. Further, because of somewhat separate cultural development, a good deal of political and institutional variability exists across EU member states, for example, their different taxation, welfare, policing, and military regimes. 5. The Costs of Secession for Each Side. 27 The EU Constitution was motivated by the desire, in the face of enlargement to 25 members of more, to enlarge and consolidate EU institutions’ powers. The adopted version, however, was by no means a complete federalist Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 20. It is worthwhile briefly reviewing how the North and South viewed the costs of secession should it actually occur. There are interesting analogies for the European Union. Costs of Southern Secession, for Each Side. It is perhaps typical that the reasons the fire-eaters gave for why secession would have no consequences were so flattering to themselves and their fellow Southerners. Self-confidence and dreams of a great future lend themselves to minimizing doubts and denigrating nay-sayers. Political agitation for an act as important as secession cannot afford to admit the intellectual possibility that action will lead to disaster and that the probabilities of disaster are largely unknown and unknowable. Northern reactions to Southern threats of secession are understandable. Northerners had heard southern threats for decades, and nothing ever came of the threats except payoffs to the South. The North was tired of the threats and tired of the payoffs. The South was never satisfied and would never shut up. Southern orators were largely long-winded blowhards whose threats were a combination of risible and insulting to Northern listeners.28 Southern orators in Congress stressed the aristocratic nature of the South, though Northerners thought of "aristocrats" as counter to American ideals, especially Americans who were soi-disant aristocrats. The South looked like a primitive part of the country that was falling behind. Southerners were only too aware that they were making minimal contributions to belles lettres, science and manufacturing, and Northerners could see it too. Most emigrants went to the North, not the South, voting for opportunity with their feet. Northern population ballooned, the South was relatively stagnant. Railroads were "the wave of the future" in the North, but the South was far behind the North in rail miles. success. The adopted version actually adds more to national governments’ freedoms in some areas, and the drafters lost the proposed power for taxation issues to be settled by qualified majorities. 28 An exception was John C. Calhoun (Niven 1988), the prominent South Carolina constitutional thinker and orator who died in 1850. Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 21. Costs of Secession from the EU, for Each Side. Euro-federalists can argue that no country will secede, or if one or a few do, the costs will be unimportant.29 Perhaps the seceding countries will simply join the European Economic Area; surely no one will want to give up the EU’s huge single market. Expelling Denmark or Sweden will teach the rest a lesson. Getting along without such small countries as Denmark or Sweden will have no detectable costs—and perhaps benefits, if other countries learn to fall into line. The Southern fire-eaters greatly oversold the importance of cotton to the North and the rest of the world. Similarly, euro-federalists may well be overselling the importance of access to the EU’s single market. For one thing, when a country joins the EU, it is subjecting itself to both trade creation and trade diversion. The benefits of joining some free trade area may be obvious as opposed to being outside all free trade areas. It is not clear, however, that membership in the EU is superior to membership in all of the possible free trade areas from which the EU member state might reasonably be able to choose. The secessionists can tell themselves that they can form a union with all the benefits and few of the drawbacks of the EU. The European Free Trade Area (EFTA) founded in the 1950s as a rival to the European Economic Community of The Six, did not work out—but a new rival to the EU might. One possibility might be a free trade area with the U.S. (A customs union might be possible but would be substantially more difficult to negotiate.) The U.S. certainly would not want to take European countries into its federal union, so European states would face no danger of “creeping federalism” as in the EU. 29 Why does the EU Constitution allow secession which creates foreseeable instability? One view is that it is not time yet to establish a new confederated country. Member states joined the EU for their own interests, instead for whole Europe. “Summary of the agreement on the Constitutional Treaty” (06/28/04) states “…allow us to call this basic text our ‘Constitution’… In legal terms, however, the Constitution remains a treaty…” Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 22. If the EU faces the danger of breaking up as the Union did, then “federalism” will play the role for the EU that slavery did for the U.S. If the EU breaks up, the chances of a civil war as a direct consequence of the break up are minimal, likely negligible. But if the EU collapses, the chance is greater for a subsequent European war in the absence of the restraints the EU imposes. As far as peace goes, is the EU just a transitory institution needed to get Europe through the 50 years after 1951 or 1957? Or is the EU necessary for peace over the long term, necessay for peace for the future so long as almost forever? Surely Estonia or Denmark can leave without harming the EU’s effect on European peace. But how far can disintegration go before the EU collapses? Or put it another way. What kind of rump EU will be unable to fulfill its role of ensuring peace in Europe? It is possible that the EU could collapse back to The Six of 1957 with no effect on European peace—but times are very different from 1957. Belgium and Luxembourg seem willing to follow implicitly the lead of France and Germany under almost any circumstances, but Italy and the Netherlands may find a new version of The Six intolerably confining and French-German dominance unbearable. It is possible that Germany and France could not live together in a EU as small as The Six. For successful integration, it may be that The Six was necessarily just a transition stage to a larger Community and eventually a Union, whether the members of The Six understood this in 1957 or not. 6. Summary and Some Conclusions. Eventually, fire-eaters who wanted to cause secession of Southern states from the Union were successful. It took them decades to reach success. Along the way, they often looked like jokes, and their rhetoric often seemed overblown and out of touch with reality. The fire-eaters were never a very large group. Their plots sometimes never got off the ground at all. And when their plots got off the ground, as in 1833 and 1850, the plots fail ignominiously. The fire-eaters looked like fools, and their supporters got a lesson of burned fingers from playing with fire. But Chapter 8. “Conditional” Unionists and the Fire-Eaters’ Conspiracy. P. 23. the fire-eaters kept trying and eventually succeeded in 1860-1861. They only had to succeed once to get what they wanted, no matter how many times they failed. The fire-eaters failed many times, but they always kept plotting and hoping because they had the raw materials they needed if they were to succeed—they had "conditional" unionists. If a good share of the Southern population would stay in the Union only if certain conditions were met, the fire-eaters could work to increase this share, to make the conditions more stringent, to convince Southerners that the conditions were not being met, to put Northerners in the position of having to violate some of the conditions. The percentage of "conditional" Unionists in the EU is unknown, but every member country has its fire-eaters who want to see their country secede. Some of these fire-eaters are beginning to join with their fellows in other countries. Like the pre-Civil-War fire-eaters, they are beginning to see that they are more likely to be successful in inducing secession if they can get a number of member states to go out at more or less the same time, and join together in a group that stands an arguably good chance of being successful.