Lexical structure of bound morphemes and

advertisement

J. Emonds, May 2009, Topic 2

Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

LEXICAL STRUCTURE OF BOUND MORPHEMES/ COMPOUNDING

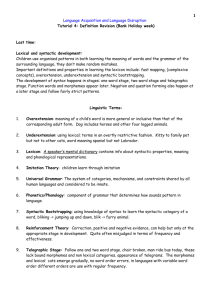

FORMAL SPECIFICATIONS OF VOCABULARY ITEMS

University of Newcastle, Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

I. Branching X0 structures in Compounds

The branching structures in (1) for English compounds all share syntactic distribution with the

category of their right hand member, as captured by Lieber’s (1980) Right Hand Head rule.

And other syntactic considerations justify also specifying the left branches with X0 categories.

(1)

a. Examples of lexically stored compounds:

[N [N Chicago ] [N pizza ] ]

[N [N Chicago ] [N Bears ] ]

[A [N camera ] [A ready ] ]

[N [N iron ] [N monger ] ]

[V [N baby ] [V sit ] ]

[N [P away ] [N game ] ]

[N [A divine ] [N right ] ]

[V [P over ] [V act ] ]

b. Examples of productive compound patterns:

[N [N Chicago ] [N man ] ] man = /mǽn/

[N [N Chicago ] [N disaster ] ]

[A [N camera ] [A free ] ]

[N [N idea ] [N monger ] ]

[V [A quick ] [V dry ] ]

[N [P away ] [N schedule ] ]

[N [N desert ] [A dry ] ]

[V [P under ] [V rehearse ] ]

Exercise: Give 8 more examples (one for each pattern), and say which ones are novel or stored.

As promised, here are more non-ideological –ism words: cynicism, euphemism, formalism,

lyricism, neologism, ostracism, skepticism, syncretism, symbolism, terrorism, truism, witticism.

II. Principles for English Stress Domains

In the system for compounds in Chomsky and Halle’s Sound Pattern of English (1968), whose

essentials I adopt, the input of English compound stress are previously word-stressed pairs of X0.

That is, each member first receives stress like words in isolation: ChicAgo, pIzza, cAmera,

rEAdy, bAby, awAy, divIne, Over, disAster, idEa, dEsert, rehEArse, etc. Thus, the examples (1)

show that English word stress rules first apply in minimal X0 domains, prior to compound stress.

(2)

Word Stress. The initial domains for assigning word-internal stress are the shortest

strings within X0-labelled brackets [ … ].

(3)

Compound Stress. Compound stress is assigned in branching X0 domains [ [ …] [….] ].

N-headed and V-headed compounds are left hand stressed, though Adj-headed compounds often

have right hand stress (camera-ready, desert dry, dark green, stress free; cf. Bates, 1988).

Consider now minimal English words with affixes. The same kinds of syntactic justifications

used to establish the categorial structures in (1) lead to similar structures for bound morphemes:

(4)

LF structures for bound morphology:

a.

[N [N clergy ] [N man ] ]

[A [N manage ] [A able ] ]

[N [P together ] [N ness ] ]

[N [V manage ] [N ment ] ]

[V [A quick ] [V en ] ]

[V [P for ] [V get ] ]

1

J. Emonds, May 2009, Topic 2

b.

Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

[N [A divin(e) ] [N ity ] ]

[A [N ocean ] [A ic ] ]

[N [N Chicago ] [N an ] ]

[N [V distribut(e) ] [N ion ] ]

[V [A solid ] [V ify ] ]

[A [V contemplat(e) ] [A ive ] ]

Now, I earlier concluded that the defining—in fact the only—characteristic of English bound

morphology is that the affixes X0 in (4) lack the individual stresses needed for compound stress.

English Morphology (descriptive): If a bound morpheme μ has no LF features except

syntactic head features F, then μ lacks any stress prior to combining in larger PF domains.

(5)

More precisely, items as in (4) will get correct stress via Principles (2) and (3) only if their PF

structures are exempted from (3) by virtue of having the PF structures (6) rather than as in (4).

(6)

English PF structures for bound morphology:

a.

[N [N clergy ] man ] man = /mən/

[A [N manage ] able ]

[N [P together ] ness ]

b.

[N [A divin(e) ] ity ]

[A [N ocean ] ic ]

[N [N Chicago ] an ] -an = /ən/

[N [V manage ] ment ]

[V [A quick ] en ]

[V for [V get ] ]

[N [V distribut(e) ] ion ]

[V [A solid ] ify ]

[A [V contemplat(e) ] ive ]

Word Stress (2) now applies to the inner domain [ … ], but neither (2) nor (3) can apply to the

outer domain. This fully explains the absolute lack of effect on stress of so-called “stressneutral” English affixes, such as -man,, -ment, -able, -en, -ness, for- as in (6a). 1

We come back in Section IV to the “stress-affecting” affixes in (6b).

.

An artificially long example can demonstrate how PF bracketing as in (6) is appropriate for the

typical “root only” stress of stress-neutral suffixes (Kiparsky’s “level 2” suffixes):

(7)

a. LF: [N [A [N [V [A sweet ] [V en ] ] [N er ] ] [A less ] ] [N ness ] ]

b. PF: [N [A [N [V [A sweet ] en ]

er ]

less ]

ness ]

Word Stress (2) applies only to sweet, since no other domains […] are minimal. There are no

domains satisfying Compound Stress (3) either, thus deriving the correct stress pattern 1-0-0-0-0.

Let’s now formalize the principle (5) that describes the correct PF structures in (6). At Spell Out

as in LF, these items have syntactic representations as in (4). We can the restate (5):

(8)

English “Morphology”: If a daughter X0 of a branching Y0 has no features other than

syntactic head features Fi, then Y0 exits the syntax into PF with no X0 label.

(8) is then a general principle that characterizes English bound morphology. It covers both

non-head prefixes as well as head suffixes. Notice that (8) affects stress but doesn’t mention it.

Recall that the “syntactic Fi” in (8) are by definition used in the syntactic component, so that (8)

is a purely syntactic statement. Syntactic structures are its input, which mentions only: X0, Y0,

Note the contrast between male /mǽn/ (a stressed compound head with gender) and, modulo political

correctness, a genderless +human suffix /mən/, e.g., female clergymen, lady postman, freshman girls, etc

1

2

J. Emonds, May 2009, Topic 2

Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

daughter, syntactic feature Fi, head. Every term is part of the syntactic model. Its output is also

syntactic, i.e., the syntactic structures used for the PF interface.

(8) has derived correct PF structures for English bound morphology (6) with no mention

of “boundaries,” morphological or otherwise, nor any mention of morphological entities.

Though (8) is not a type of rule encountered in syntax before, it has vast empirical

support, and allows us to dispense with an entire component, namely “Morphology.”

III. Formal specifications of vocabulary items

Before developing an analysis of “level 1” or stress-affecting suffixes, I must introduce some

formal aspects of lexical formatting, which is in fact the central task before us in this course.

Emonds (2002) argues for a certain formal notation for grammatical items in the lexicon (= store

of vocabulary). It focuses on the availability of parentheses and Ø in all parts of lexical entries.

(9)

Lexical Format: π, σ, < σ’ >, λ

π = phonological representation. A later Topic will give some items with obligatorily

null allomorphs (π = Ø) and others with optionally null allomorphs (parenthesized π).

σ = Ø for gosh, ouch, yes, bravo, whoops, etc. The more interesting case where σ is

parenthesized plays a central role in analyzing e.g. certain passive inflections, which can

be grammatically adjectival but are not (necessarily) interpreted in LF as adjectives.

λ are purely semantic features f occurring only with open class items. I don’t consider

them to be successfully formalized. As claimed in (8) they are entirely absent in entries

for bound morphology.

< σ’ > specifies contextual insertion features, as developed in Emonds (2000: Ch. 3).

(i) If < σ’ > = < Fi >, then π is a free morpheme and the Fi are the head features of a

selected phrase XP, where some projection of X0 is a sister of [σ π ].

(ii) If < σ’ > = < Fi ___> or <___Fi>, then π is a bound morpheme under some X0, and

the Fi are the head features of a selected sister of [σ π ].

To see how this formalism for contexts works, we examine two lexical entries (10)-(11) that

combine (i) and (ii).

(10)

able, A, POTENTIAL, < V(___) >

< V___ > licenses: [A [V manage] [A able]], forgiv(e)-able, liv(e)-able, perish-able, etc.

<V > licenses: able [IP [DP Ø] [to] … [VP … [V manage/ forgive/ live in/ perish ]… ] ]

The terminal string inside the IP sister of able but outside the selected VP must be Ø when able

selects <V>, i.e. in narrow syntax but not necessarily in PF. By the way, this satisfactorily

accounts for obligatory control; Emonds (2000: Ch.7) explains details.

3

J. Emonds, May 2009, Topic 2

(11)

Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

free, A, < [+N, -V] (___) >, +fi

Let us assume that DP and N are both selectable by the features [+N, -V]. Entry (11) yields both

the pattern content-free, humor-free, emotion-free, jealousy-free and also the pattern free of all

content, free of tasteless humor, free of so many emotions, free of his jealousy.

Example (10): –able uses (____) and is a level 2 (stress-neutral) suffix without any fi.

Example (11): free uses (____) and is an open class morpheme with fi and so this gives

rise to compound stress.

Compare free with devoid:*content devoid, *humor devoid, *emotion devoid *jealousy devoid.

(12)

devoid, A, < [+N, -V] >, +fi, +fk

IV. Representing the Romance/ Latinate “Level 1” suffixes of English

Let’s turn to English “stress-affecting” or “level 1” suffixes. Their LFs are as given in (4b):

(6b)

[N [A divin(e) ] ity ]

[A [N ocean ] ic ]

[N [V distribut(e) ] ion ]

[V [A solid ] ify ]

[A [V contemplat(e) ] ive ]

[N [N Paris ] ian ]

(13)

-ic, A, <N___>

-ity, N, <A___>

-ify, V, <A___>

However, their PF structures should be based rather on (6b), since English Morphology (8) will

automatically replace (13) with these latter representations. Their appropriate PF bracketings

seem to additionally lack internal brackets around the stems.

(14)

[N divin(e) ity ]

[A ocean ic ]

[N distribut(e) ion ]

[V solid ify ]

[A contemplat(e) ive ]

[N Paris ian ]

With “erased” internal brackets, Chomsky and Halle’s (1968) “word-level phonology” assigns

stress to these items directly, on the underlined syllables. “Level 1” suffixes thus have an itemparticular property that their stems fail to qualify as stand alone domains for Word Stress (2).

So we need an item-particular device to cancel the stress domain of the roots of these affixes.

To achieve this, I will use contextual insertion features which have the feature Ø. At first this

will seem like an unintuitive trick.

In general, Ø is a feature meaning “missing at an interface.” Exactly what is missing at which

interface depends on where Ø appears among the π, σ, and σ’ in a lexical entry. We have seen

in (9) what Ø means as a value of π and σ. What about in context features σ’?

Recall that ever since Chomsky (1965: Ch. 2), subcategorization for an absent contextual frame

is unmarked. That is, the symbol Ø is never used or needed for licensing a null syntactic

context. In a context specification we can thus use Ø for some other purpose.

(15)

The Feature Ø in contextual features (tentative). Ø as a feature in <[F,Ø]___> or

<___[F,Ø]> means that F appears in LF but does not exit narrow syntax into PF.

4

J. Emonds, May 2009, Topic 2

Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

With the notation (15), I propose to now rewrite the level 1 suffix entries above in (13):

(16)

-ic, A, <[N,Ø]___>

-ity, N, <[A,Ø]___>

-ify, V, <[A,Ø]___>

This notation is appropriate for any English level 1, Latinate suffixes. By using (15) we derive

the needed contrasting representations given in (17).

(17)

a. Uniform LFs:

[N [A divin(e) ][N right/ ness/ ity ]]

PFs: [N [A divine ][N right ]]

[N [A divine ] ness ]

[N divine ity ]

b. Uniform LFs:

[A [N ocean ][A like/ less/ ic ]]

PFs: [A [N ocean ][A like ]]

[A [N ocean ] less ]

[A ocean ic ]

c. Uniform LFs: [N [V pronounc(e/i) ][N ment/ ation ]]

PFs:

[N [V pronounce ] ment ] [N pronunci ation ]

The “word level phonology rules” of Chomsky and Halle’s Sound Patterns can now derive all

these examples.

Exercise: One problem remains, namely that a domain for ability in (18) seems missing. Try to

see why this is a problem, and any constructive proposal will certainly be cited!

(18)

LF:

PF:

[N [A [V [A [N nation ] [A al ] ] [V ize ] ] [A able ] ] [N ity ] ]

[N [V nation al ize ] able ity ] ]

↑

↑

↑

↑

level 1 level 1 level 2 level 1

Digression. In such a system a null level 1 suffix has no effect at all in English pronunciation,

since it has no segments or brackets in PF, and its sister’s brackets (labels) are also absent in PF.

However, a null level 2 (stress-neutral) suffix would result in two sets of brackets around a

stem. This could conceivably have consequences, but also, it might also have none at all.

Chomsky and Halle (1968) argue that dual internal brackets can play a role in their word level

stress, but their argumentation is unconvincing. They claim that there are PF-null nominal

brackets around a verb torment, and that the resulting “2 word-internal cycles” cause the

secondary stress in the noun torment, in contrast to a pure noun torrent with reduced 2nd vowel.

However, this secondary stress is not caused by “2 cycles” but by the double consonant, as

shown by the identical secondary stresses on many –ment nouns with several different internal

structures: ailment, augment, adornment, basement, figment, (in)vestment, pigment.

We have thus achieved proper specifications of stress and X0-internal phonological domains

with no morphology-specific devices, symbols, principles, categories, or boundaries.

Principle (8) for English holds generally for the syntax-PF interface, and (15) defines a

notational convention for the symbol Ø when it appears in a contextual feature of lexical entries.

Motivation. Standing back, we can ask: Why should English have a principle such as (8), or a

device in its lexical structure (15) that allow fewer domains to be specified in PF than in LF?

PF is an area of physical effort, at least for production. In particular, English stress domains,

with its accents realized by what is cross-linguistically notable amplitude, always require effort.

5

J. Emonds, May 2009, Topic 2

Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

It is then clearly more economical in English to have fewer domains at the interface of physical

production. This economy of physical effort is precisely what principles (8) and (15) achieve.

In contrast, French intonation and stress pay no attention to syntax-based or lexically-based

word-internal domains. Hence a principle like (8) or device (15) would amount to unmotivated

formal complications in French, with no pay-back. Hence they have no counterparts in French.

In conclusion, note that Economy is what makes the reduction of English stress in domains that

contain suffixes obligatory.

References for Topics 1 and 2

Anderson, Stephen. 1982. “Where’s Morphology?” Linguistic Inquiry 13. 571-612.

Aronoff, Mark. 1976. Word Formation in Generative Grammar, MIT Press, Cambridge.

Baker, Mark. 1988. Incorporation: A Theory of Grammatical Function Changing, University of

Chicago Press, Chicago.

---- 1985. “The Mirror Principle and Morphosyntactic Explanation,” Linguistic Inquiry 16, 373416.

Bates, Dawn. 1988. Prominence Relations and Structure in English Compound Morphology.

University of Washington doctoral dissertation.

Chomsky, Noam.. 1957. Syntactic Structures, Mouton, The Hague.

Chomsky, Noam. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Chomsky, Noam and Morris Halle. 1968. The Sound Pattern of English. Harper and Row, New

York

Emonds, Joseph. 2000. Lexicon and Grammar: the English Syntacticon. Mouton de Gruyter,

Berlin.

Emonds, Joseph. 2002. Formatting Lexical Entries: Interface Optionality and Zero. Theoretical

and Applied Linguistics at Kobe Shoin 5: 1–22.

Greenberg, Joseph. 1963. “Some Universals of Grammar with Particular Reference to the Order

of Meaningful Elements,” Universals of Language, J. Greenberg (ed.). MIT Press,

Cambridge.

Grimshaw, Jane. 1979. “Complement Selection and the Lexicon,” Linguistic Inquiry 10, 279326.

Halle, M. and A. Marantz. 1993. “Distributed Morphology and the Pieces of Inflection,” in K.

Hale and S. J. Keyser, eds., The View from Building 20: Essays in Linguistics in Honor of

Sylvain Bromberger, MIT Press, Cambridge, 111-176.

Hoeksema, Jack. 1988. “Head-types in Morpho-syntax,” Yearbook of Morphology, G. Booij and

J. van Marle, eds. Foris Publications, Dordrecht, 123-137.

Lieber, Rochelle. 1980. The Organization of the Lexicon. MIT doctoral dissertation.

Lieber, Rochelle. 1983. “Argument Linking and Compounds in English.” Linguistic Inquiry 14.

251-286.

Lieber, Rochelle. 1992. Deconstructing Morphology, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Maylor, B. Roger. 2002. Lexical Template Morphology: Change of state and the verbal prefixes

of German, John Benjamins, Amsterdam.

Selkirk, Elisabeth. 1982. The Syntax of Words, MIT Press, Cambridge.

Walinska de Hackbeil, Hanna. 1985. “En-Prefixation and the Syntactic Domain of Zero

Derivation,” Proceedings of the 11th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society,

University of California Linguistics Department, Berkeley.

6

J. Emonds, May 2009, Topic 2

Structure of the Syntax-Lexicon Interface

Appendix. The Syntactic Feature Ø on subcategorized phrasal complements

Despite (15), the simplest phrasal contextual feature <[F,Ø]> is still undefined. In this regard,

Emonds (2002) discusses notation for the null discourse anaphors of Grimshaw (1979).

(19)

We don’t know when the game starts. So I must soon { ask/ find out/ *tell/ *figure out }.

Jim is driving into the office today.

Sue will { go/ come/ *head/ *walk / *drop / *get } later.

Sue will { go/ come/ head/ walk / drop / get } in later.

I have keys for the house. How soon can I { enter /take over /*occupy /*empty out}?

So only some verbs obligatorily subcategorized for an overt XP (i.e. ask, find out, go, come,

enter, take over) allow a phonetically null XP to be interpreted from context.

(20)

a. So John should soon figure { it/ that/ something / *so/ *Ø } out.

b. So John should soon find { it/ that/ something / *so/ Ø } out.

These two verbs take a DP or a CP complement. Let’s create a notation for the contrast seen in

(20) as in (21). (The feature [C,-GOAL] excludes for-to clauses.)

(21)

a. figure out, V, Fi, <{D / [C, -GOAL] }>, fj

b. find out, V, Fi, <{ [D, (Ø)] / [C, -GOAL] }>, fk

This notation [D, Ø] should imply that a complement B is obligatory at LF but phonetically

null. For find out the other choices for a complement are among overt DP (the answer), a thatclause or an indirect question.

Let’s get this result by first generalizing (15) to (22):

(22)

The Feature Ø in contextual features. [F,Ø] in any contextual feature <σ’> means that

the category F appears in LF but does not exit the syntax into PF.

A null discourse anaphor is optional with the verb find out, so (Ø) rather than Ø appears in (21b).

But once a null anaphor is licensed, Economy then prefers it to a minimal phonetic anaphor it.

There is an important difference between <[B, Ø]> and <[B, Ø]___>. Word internally (see

section IV), the lexical specification <[B, Ø]___> means that only the category B is missing in

PF, while the pronounceable material dominated by B remains.

But <[B, Ø]> means that all of B is phonetically null in PF.

The definition (22) confirms that the use of Ø in context features is not limited to word-internal

syntax, what some might call morphology. Like every other device in syntactic and lexical

theory, it is more general than morphology. Counter to Aronoff (1976), morphology is not an

area “unto itself.”

7